9.3 Sea-Level Change

Steven Earle and Laura J. Brown

Sea-level change has been a feature on Earth for as long as there have been oceans (billions of years), and it has important implications for coastal processes and both erosional and depositional features. There are three main mechanisms of sea-level change, as described below.

Eustatic sea-level changes are global sea-level changes related either to changes in the volume of glacial ice on land or to changes in the shape of the seafloor caused by plate tectonic processes. For example, changes in the rate of mid-ocean spreading will change the shape of the seafloor near the ridges, and this affects the sea level.

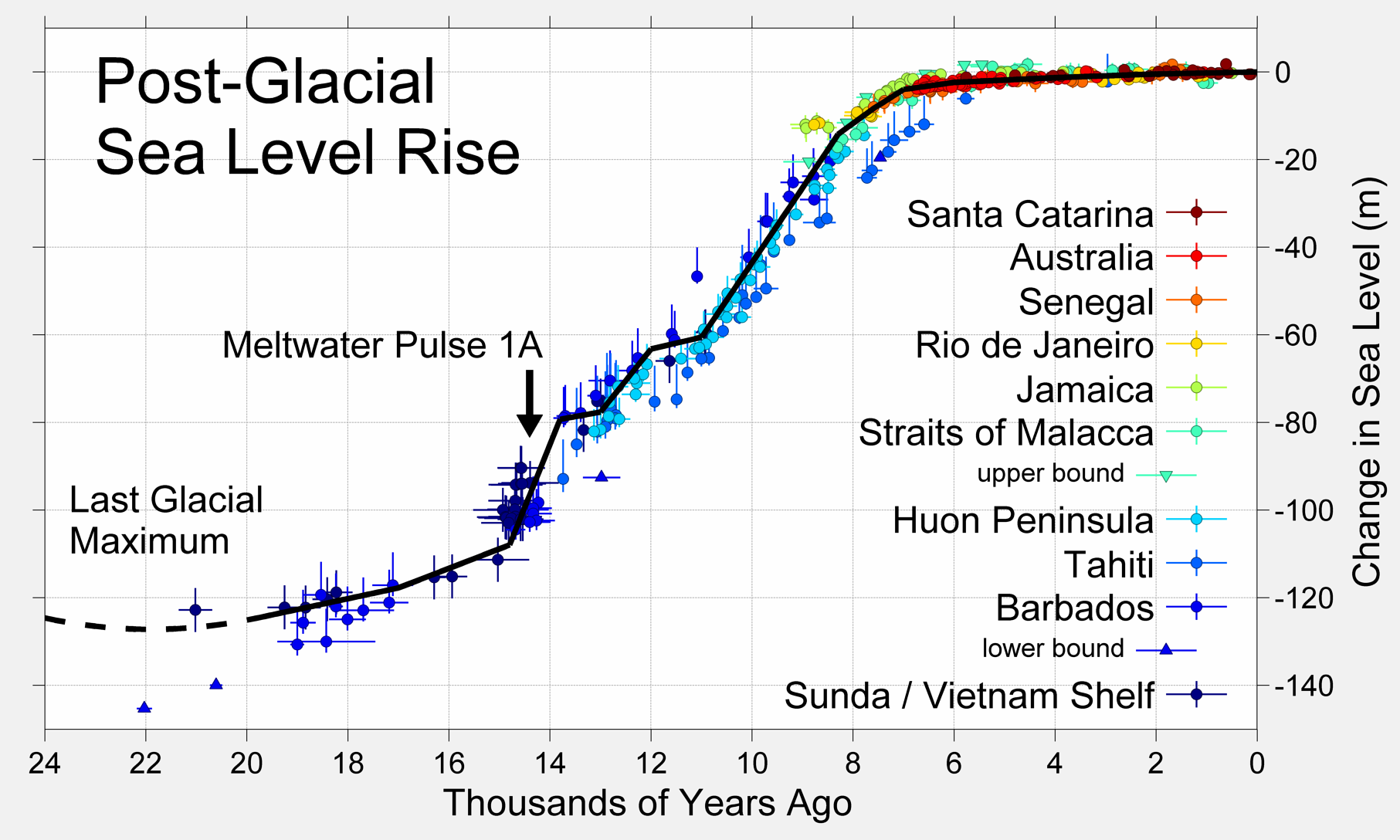

Over the past 20,000 years, there has been approximately 125 m of eustatic sea-level rise due to glacial melting. Most of that took place between 15,000 and 7,500 years ago during the major melting phase of the North American and Eurasian Ice Sheets (Figure 9.16). During that time the average rate of sea-level rise was approximately 14 mm/y. At around 7,500 years ago, the rate of glacial melting and sea-level rise decreased dramatically. The average rate over the past 6000 years has been 0.5 mm/y. Anthropogenic climate change led to accelerating sea-level rise starting around 1870. Since then the average rate has been about 1.1 mm/y, but it has been gradually increasing. The current rate is over 3 mm/y.

Isostatic sea-level changes are local changes caused by subsidence or uplift of the crust related either to changes in the amount of ice on the land or to the growth or erosion of mountains.

Almost all of Canada and parts of the northern United States were covered in thick ice sheets at the peak of the last glaciation. Following the melting of this ice there has been an isostatic rebound of continental crust in many areas. This ranges from several hundred metres of rebound in the central part of the Laurentide Ice Sheet (around Hudson Bay) to 100 m to 200 m in the peripheral parts of the Laurentide and Cordilleran Ice Sheets—in places such as Vancouver Island and the mainland coast of B.C. In other words, although global sea level was about 130 m lower during the last glaciation, the glaciated regions were depressed at least that much in most places, and more than that in places where the ice was thickest.

There is evidence of isostatic rebound along the southwest coast of Vancouver Island, where a number of streams enter the ocean as 5 m high waterfalls, as shown in Figure 9.17.

Tectonic sea-level changes are local changes caused by tectonic processes. The subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate beneath British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and northern California is creating tectonic uplift (about 1 mm/year) along the western edge of the continent, although much of this uplift is likely to be reversed when the next large subduction-zone earthquake strikes.

Coastlines in areas where there has been a net sea-level rise in the geologically recent past are commonly characterized by estuaries and fjords. Howe Sound, north of Vancouver, is an example of a fjord (Figure 9.18). This valley was filled with ice during the last glaciation, and there has been a net rise in sea level here since that time. Coastlines in areas where there has been a net sea-level drop in the geologically recent past are characterized by uplifted wave-cut platforms (shown in Figure 9.12). Uplifted beach lines are another product of relative sea-level drop, although these are difficult to recognize in areas with vigorous vegetation. They are relatively common in Canada’s far north.

Exercise 9.4 A holocene uplifted shore

The blue-grey sediments in the photo contain marine fossils of early Holocene age (~12,500 years ago) situated at about 60 m above sea level on Gabriola Island, BC. Explain how eustatic and isostatic sea-level change processes might have contributed to the existence of these materials at this elevation.

Media Attributions

- Figures 9.16, 9.17, 9.18: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 9.19: “Post-Glacial Sea Level” © Robert A. Rohde. CC BY-SA.