1 1.1 Natural Hazards, Disasters, Risk, and Vulnerability

Laura J. Brown and R. Adam Dastrup

Natural Hazards

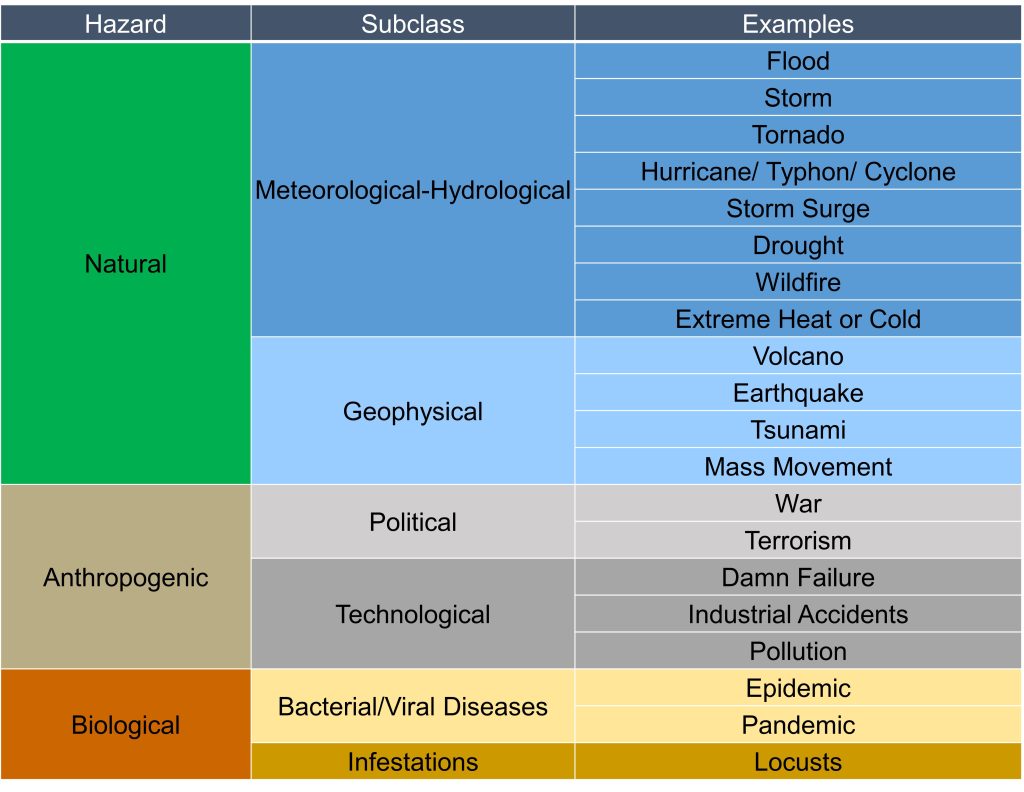

A hazard is an event that endangers human life or property or changes the environment so that human survival is threatened. The event itself is not a hazard; instead, it becomes a hazard only when it threatens human lives or property. There are various ways of classifying hazards. One way is based on the origin of the hazard. Using this origin-based system, hazards are classified as natural or anthropogenic. In this book, a natural hazard is any meteorological-hydrological or geological event that has the potential to endanger human lives or damage infrastructure.

The qualifier “natural” is crucial because it separates hazards that result from natural processes in the environment from those resulting solely from human actions. Anthropogenic hazards that arise directly from human activities such as pollution, wars, industrial accidents, and structural failure like damn bursts are excluded. Whereas events resulting from natural processes that occurred before humans evolved and would continue to exist in the absence of people are classified as natural hazards. A further distinction is made for biological hazards; these too are natural but not related to the physical environment, such as infectious diseases like COVID-19.

Many natural hazards have seasons, especially meteorological-hydrological hazards. The United States has more tornadoes than the rest of the world combined, yet they mostly only occur in the spring and early fall. Landslides are more prone in the spring when snow begins to melt, and the saturated ground triggers unstable slopes to fail. Wildfires are frequent in the middle of the summer and early fall when the land is dry, and afternoon thunderstorms in arid climates produce lightning without any precipitation. Furthermore, hurricane season in the Northern Hemisphere peaks between August and September, when the Atlantic Ocean is warmest.

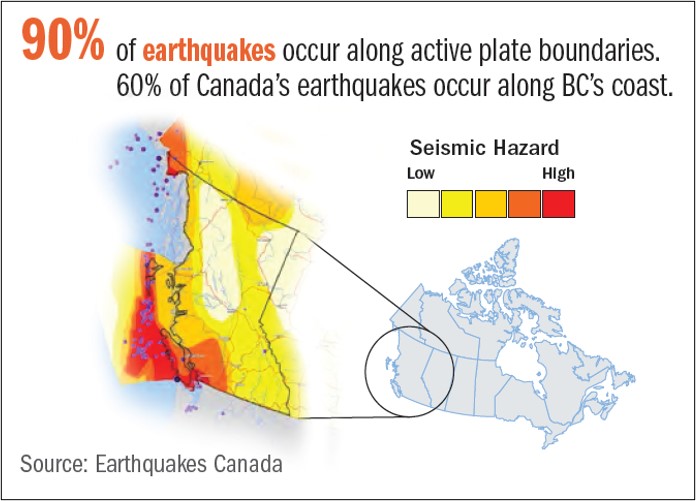

Geophysical hazards do not have a season and often strike without warning. Due to our understanding of plate tectonics, we know where earthquakes and volcanic eruptions will likely occur but not when or the magnitude of these events.

Disasters

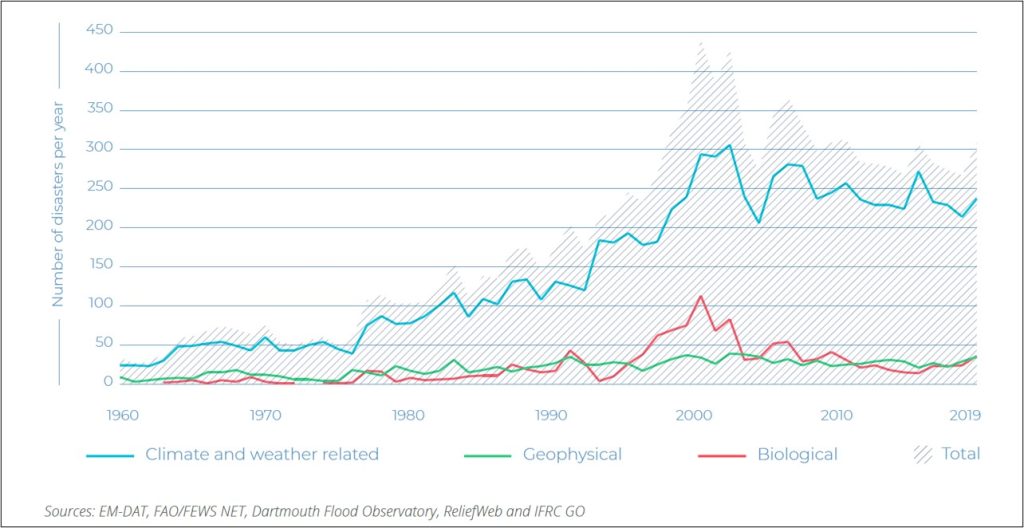

A disaster occurs when a natural hazard results in significant property damage, loss of livelihoods, injuries, or deaths. Disasters are growing in frequency and severity in Canada and around the World (Figure 1.2, Source: World Disasters Report 2020, Chapter 2 ). Between 2010 and 2019, it’s been estimated that globally 2,850 disasters were triggered by natural hazards, affecting 1.8 billion people (World Disasters Report 2020, Chapter 2). Most (83%) of these disasters were attributed to meteorological-hydrological events. Flooding is the most prevalent (1,298 events), followed by storms (589 events) and then heat waves (World Disasters Report 2020, Chapter 2).

Globally, since the 1960s, the number of disasters triggered by natural hazards has increased. The disasters related to geophysical or biological hazards have remained relatively stable since the 1980s, with approximately 25 to 50 events per year. In contrast, the number of disasters triggered by meteorological-hydrological hazards has continually increased.

A couple of factors may contribute to the increase in disasters recorded over these 40 years, unrelated to a rise in the number of natural hazards. For example, improved reporting of events in various countries and regions has occurred over time. Also, population and urbanization increase means that more people may be affected by each hazardous event. In other words, more people are exposed when a hazardous event strikes. However, these two factors alone would increase numbers across all disasters equally and cannot explain the constant rise in extreme weather and flooding events (World Disasters Report 2020, Chapter 2). Climate change is likely a factor in this increase. the increase in

Understanding Risk, Vulnerability and Exposure

In the context of natural hazards, risk refers to the likelihood (probability) of a hazardous event causing injuries, deaths, or destruction.

Risk assessments are important. They help save lives by identifying which areas, buildings, infrastructure, and people are vulnerable or more likely to experience a hazardous event. The risk of a potential hazard is defined as the probability of a hazardous event occurring multiplied by the consequence to the human environment.

Hazard Risk = Probability of Hazard x Consequence of Hazardous Event

It is essential to determine the potential risk a location has for any particular hazard to know how to prepare for one. For example, seismic hazard calculations assess the damage potential of earthquakes. The damage potential of an earthquake is determined by ground movement and shaking and how the buildings in an area are constructed. Expected ground motion for an area is calculated based on probability, such as the statistical analysis of past earthquake activity and knowledge of Canada’s tectonic and geologic structure.

Disaster Risk

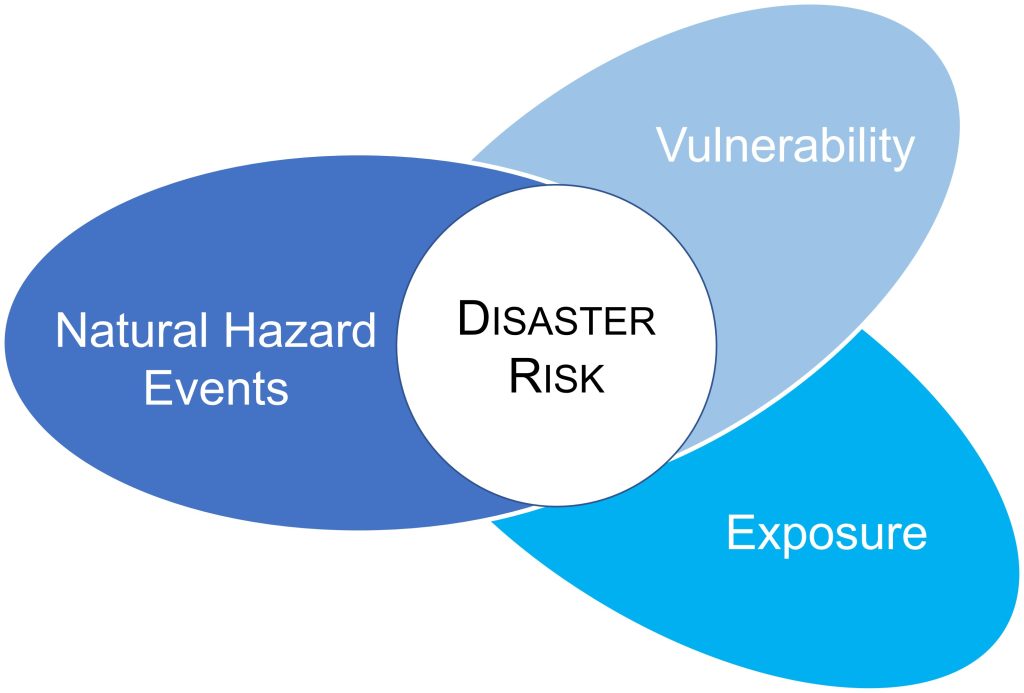

Natural hazards are inevitable; however, disasters are not. Disasters occur when a vulnerable population is exposed to a hazardous event. Disaster risk is a function of three components, the natural hazard, the vulnerability and the exposure of the people affected (Figure 1.4). It’s important to note that the severity of the hazardous event is not the sole driver of disaster risk (IPCC 2012). Let’s talk a little about what vulnerability and exposure in the context of disasters mean.

Exposure

Exposure refers to the presence of people, livelihoods, environmental resources, infrastructure, economic, social or cultural assets at a location where a hazardous event has occurred (IPCC 2012). If people and economic resources are not located in potentially hazardous areas, there would be no disaster risk. It is possible to be exposed but not vulnerable to a hazardous event. For example, Japan and Haiti are countries located along active fault lines, so they frequently experience earthquakes. Japan is a prosperous country with sufficient means to modify buildings and infrastructure to mitigate the potential damage caused by an earthquake, while Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the world. Haiti has little or no preparedness measures to protect structures from collapse during an earthquake. In 2011, Japan was struck by a 9.0 magnitude earthquake followed by a tsunami; in 2010, a lower magnitude (7.0) earthquake devastated Haiti (Figure 1.5). Despite the smaller magnitude of Haiti’s earthquake, their death toll was much greater (~220,000 UN.org/news) than Japan. In Japan, the combined earthquake and tsunami event killed approximately 20,000 people.

Vulnerability

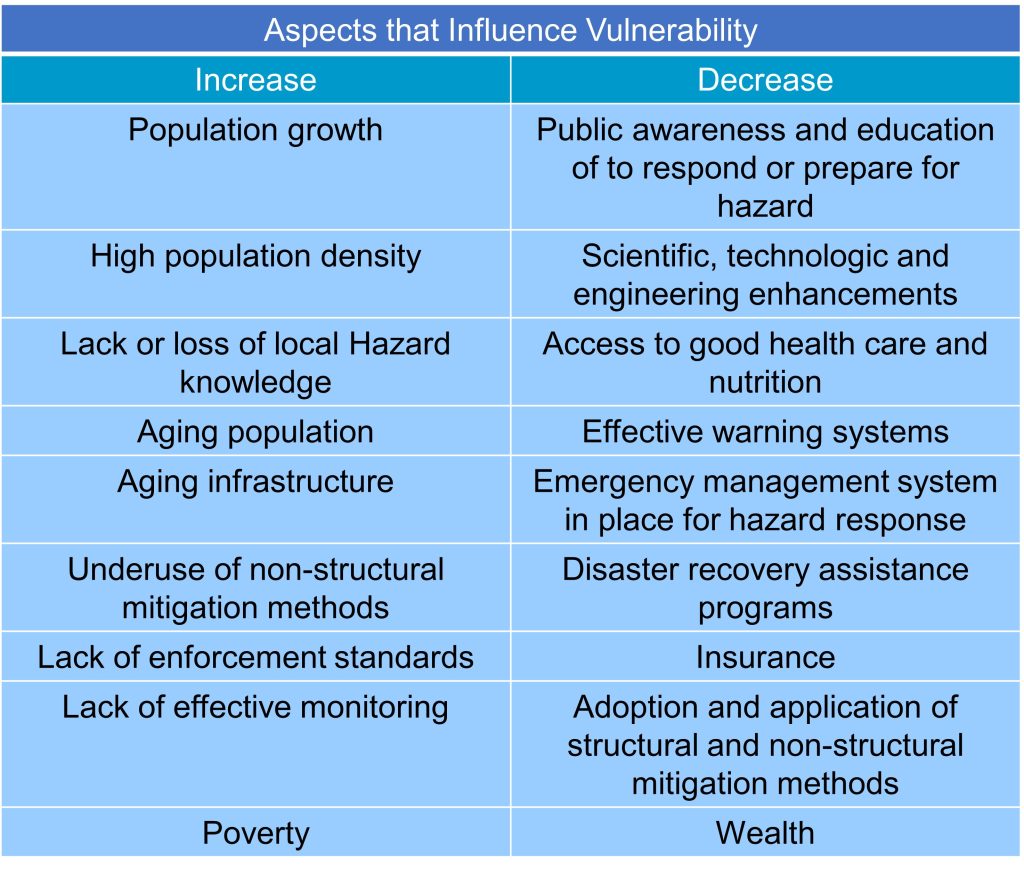

Vulnerability is the propensity to suffer adverse effects due to the impact of a natural hazard. It is defined by the characteristics of people and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist or recover from the impact of a hazardous event (IPCC 2012). Vulnerability results from a whole range of circumstances and economic, social, cultural, institutional and political factors that shape people’s lives and create the environments where they live. Some individuals are more vulnerable than others within a community. Factors influencing individuals’ vulnerability include age, health, wealth, and education. There’s also vulnerability based at the Societal level controlled by demographics, social-economic factors and governance.

Drivers of vulnerability include population growth, rapid and inappropriate or unplanned urbanization, international financial pressures, social-economic inequalities, poor governance (e.g. corruption) and environmental degradation (cited by IPCC, 2012).

Former UN Security General Kofi Annan has said, “The term natural disaster has become a misnomer increasingly. Human behaviour transforms natural hazards into unnatural disasters.” Most deaths from natural disasters occur in less developed countries. According to the United Nations, a less developed country (LDC) is a country that exhibits the lowest indicators of socioeconomic development and is ranked among the lowest on the Human Development Index. Those who live in low-income environments tend to have the following characteristics:

- Live in areas that are at a higher risk of geologic, weather, and climate-related disasters

- Live in areas that lack the economics and resources to provide a safe living infrastructure for its people

- Tend to have few social and economic assets and a weak social safety net

- Lack of the technological infrastructure to provide early warning systems

As human populations have grown and expanded and technology has allowed us to manipulate the environment, natural disasters have become more complex and arguably more “unnatural.” There are various ways humans have not only influenced but magnified the impacts of disasters on society.

Primary and Secondary Effects

There are two types of effects caused by natural disasters: direct and indirect. Direct effects, also called primary effects, include destroyed infrastructure and buildings, injuries, separated families, and even death. Indirect, sometimes called secondary effects, are things like contaminated water, disease, and financial losses. In other words, indirect effects are things that happen after the disaster has occurred.

How we chose to build our cities will significantly determine how many lives are saved in a disaster. For example, we should not be building homes in areas prone to landslides, liquefaction, or flash floods. Instead, these places should be left as open-space such as parks, golf courses, or nature preserves. This is a matter of proper zoning laws, which the local government controls. Another way we can reduce the impact of natural disasters is by having evacuation routes, disaster preparedness and education, and building codes so that our building does not collapse on people.

any natural phenomena that endangers human life, property or changes the environment so that human livelihood or survival is threatened.

spinning columns of wind attached to the base of a supercell and touching the ground. Winds can exceed 480 km/hr.

uncontrolled and unpredictable fire that burn combustible vegetation

a violent short-live weather event that generates heavy rainfall, strong wind gusts, thunder, lightening and sometime hail

large tropical cyclonic storm with strong winds (exceeding 119km/hr), torrential rainfall and storm surges

theory explaining the structure and movement of rigid lithospheric plates and the affect when they collide, subduct or slide past each other.

An assessment of the size of an event related to the energy released.