2.3 Alfred Wegener: The Father of Plate Tectonics

Steven Earle and Laura J. Brown

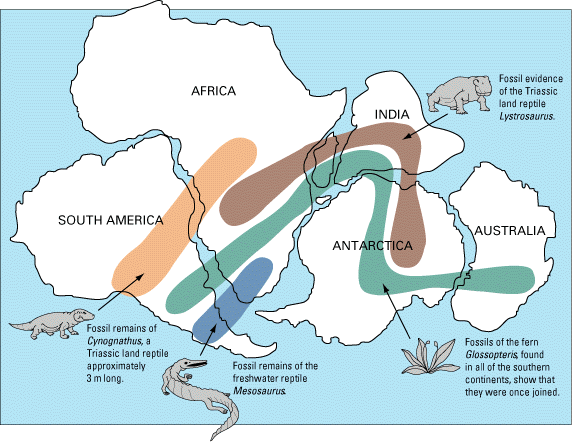

Alfred Wegener (1880-1930) (Figure 2.4) earned a Ph.D. in astronomy at the University of Berlin in 1904, but he had always been interested in geophysics and meteorology and spent most of his academic career working in meteorology. In 1911 he happened on a scientific publication that described the existence of matching Permian-aged terrestrial fossils in various parts of South America, Africa, India, Antarctica, and Australia (Figure 2.5).

Wegener concluded that this distribution of terrestrial organisms could only exist if these continents were once joined together in a supercontinent. He coined the term Pangea (“all land”) for the supercontinent, which he thought included all present-day continents.

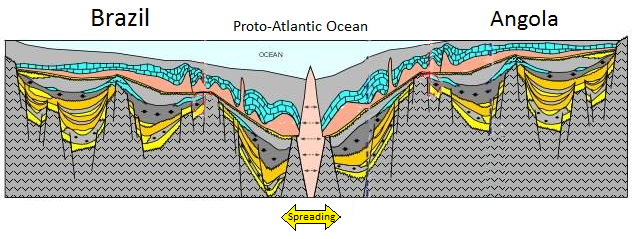

Wegener’s theory was that Pangea broke into today’s continents and drifted apart to their current locations. He called his theory Continental Drift and pursued evidence to support it—combing the libraries, consulting with colleagues, and making observations. He relied heavily on how the continents fit together like a giant jigsaw puzzle. The matching geological patterns separated by oceans, such as sedimentary strata in South America matching those in Africa (Figure 2.6), or North American coalfields matching those in Europe, and the ancient mountains ranges of Atlantic Canada matching those of northern Britain and Scandinavia —both in morphology and rock type.

Wegener also relied on evidence of glaciation patterns in South America, Africa, India, Antarctica, and Australia (Figure 2.7). He argued that these patterns of striations indicating glacial advance could only have happened if these continents were once a single supercontinent.

Wegener first published his ideas in 1912 in a short book called Die Entstehung der Kontinente (The Origin of Continents), and then in 1915 in Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane (The Origin of Continents and Oceans). He revised this book several times up to 1929. It was subsequently translated into French, English, Spanish, and Russian in 1924.

As compelling as all this evidence was, Wegener could not propose a credible mechanism for continent movement. It was understood by this time that the continents were primarily composed of sialic material (SIAL: silicon and aluminum dominated, similar to “felsic”) and that the ocean floors were primarily simatic (SIMA: silicon and magnesium dominated, similar to “mafic”). Wegener proposed that the continents were like icebergs floating on the heavier SIMA crust, but the only forces that he could invoke to propel continents around were poleflucht (a german word that translates to ‘flight from the poles’), the effect of Earth’s rotation pushing objects toward the equator, and the lunar and solar tidal forces, which tend to push objects toward the west. It was quickly shown that these forces were far too weak to move continents, and without any reasonable mechanism to make it work, Wegener’s theory was quickly dismissed by most geologists of the day.

Alfred Wegener died in Greenland in 1930 while carrying out studies related to glaciation and climate. At the time of his death, his ideas were tentatively accepted by only a small minority of geologists and soundly rejected by most. However, within a few decades, that was all to change. For more about his extremely important contributions to Earth science, visit the NASA website to see a collection of articles on Alfred Wegener.

Image Descriptions

Figure 2.5 image description: Fossils found across different continents suggest that these continents were once joined as a supercontinent. Fossil remains of Cynognathus (a terrestrial reptile) and Mesosaurus (a freshwater reptile) have been found in South America and Africa. Fossil evidence of the Lystrosaurus, a land reptile from the Triassic period, has been found in India, Africa, and Antarctica. Fossils of the fern Glossopteris have been found in Australia, Antarctica, India, Africa, and South America. When you position these continents to fit together, the areas where these fossils were found line up. [Return to Figure 2.5]

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.4: “Alfred Wegener ca.1924-30.” Public domain.

- Figure 2.5: “Snider-Pellegrini Wegener fossil map” by Osvaldocangaspadilla. Public domain.

- Figure 2.6: © Steven Earle. CC BY. Based on “Angola -Brazil sub-sea geology” by Cobalt International Energy can be found at U.S. Energy Information Administration: Country Analysis Brief: Angola (May 2016) [PDF].

- Figure 2.7: “Karoo Glaciation” © GeoPotinga. Adapted by Steven Earle. CC BY-SA.