7.5 River Flooding

Steven Earle and Laura J. Brown

A river floods when the water normally flowing in the channel overflows its banks and spreads out onto the surrounding land.

Why do rivers flood? Physical causes of flooding are related to surface runoff. Soils have the ability to absorb water called the infiltration rate. Infiltration occurs when water is absorbed by the soil and drains down through the ground to become groundwater. When the surface is unable to absorb rainfall or snowmelt, the water pools at the surface. This pooled water becomes runoff or overland flow and drains towards creeks and rivers adding lots of water. There are several factors that control whether rainfall or snowmelt can infiltrate the surface. For example, intense heavy rainfall delivers water at a rate too high for the soils’ infiltration capacity, so some will be absorbed but the rest will form puddles or result in flooding. Other natural factors include long periods of rain, where the ground becomes very wet, and saturated soils. In saturated soils, all the available pore space is filled with water, so these soils can not absorb any more water. Impermeable surfaces due to frozen soil, or rock don’t allow water to infiltrate so all incoming rainfall and/or snowmelt ponds on the surface. Finally, the steepness of the slope influences the infiltration runoff relationship. On shallow slopes, water ponds at the surface and then slowly drains into the soil through infiltration or is lost through evaporation. On steep slopes the water doesn’t form puddles but flows downslope over the surface, this is surface runoff or overland flow. Surface runoff carries the excess water to creeks and rivers rapidly. Additional water dumped into streams due to surface runoff increases the discharge of the river and if the channel can not contain this additional water flooding occurs.

Human impact on the environment can increase the flood risk due to urbanisation because towns and cities have more impermeable surfaces and deforestation because removing trees reduces the amount of water intercepted and increases runoff.

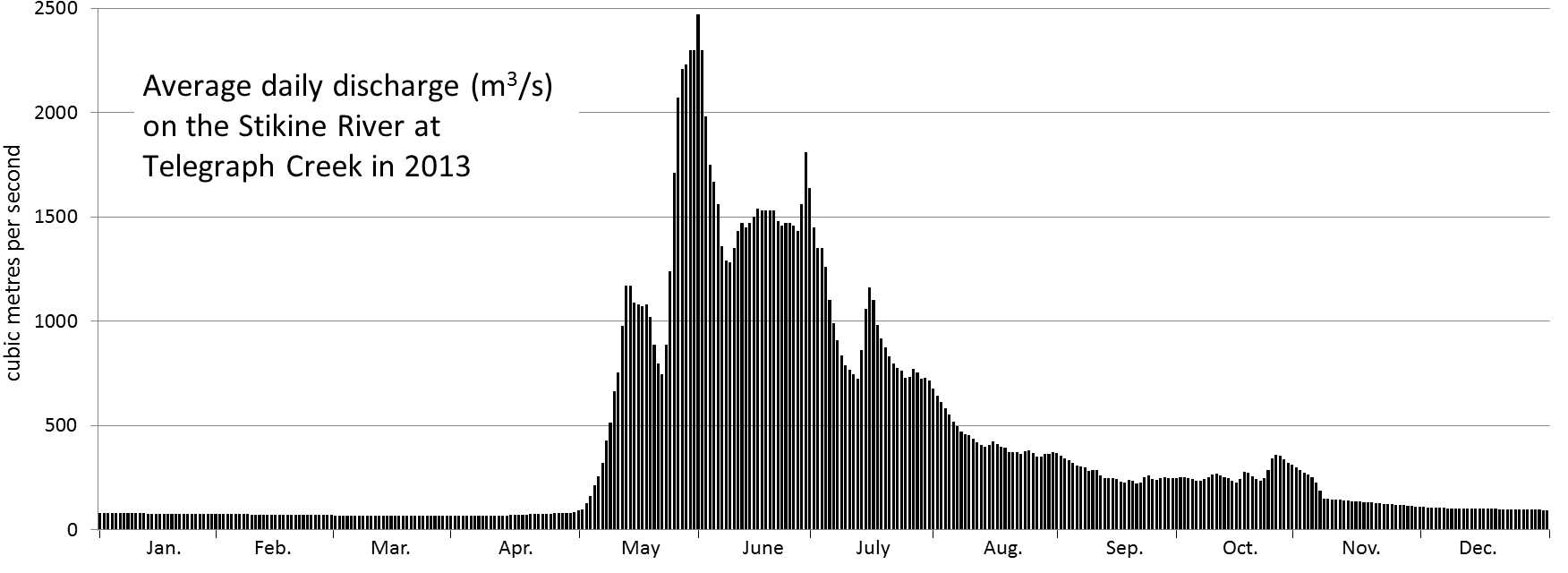

The discharge levels of streams are highly variable depending on the time of year and on specific variations in the weather from one year to the next. In Canada, most streams show discharge patterns similar to that of the Stikine River in northwestern B.C., as illustrated in Figure 7.5.1. The Stikine River has its lowest discharge levels in the depths of winter when freezing conditions persist throughout most of its drainage basin. Discharge starts to rise slowly in May, and then rises dramatically through the late spring and early summer as a winter’s worth of snow melts. For the year shown, the minimum discharge on the Stikine River was 56 cubic metres per second (m3/s) in March, and the maximum was 37 times higher, 2,470 m3/s, in May.

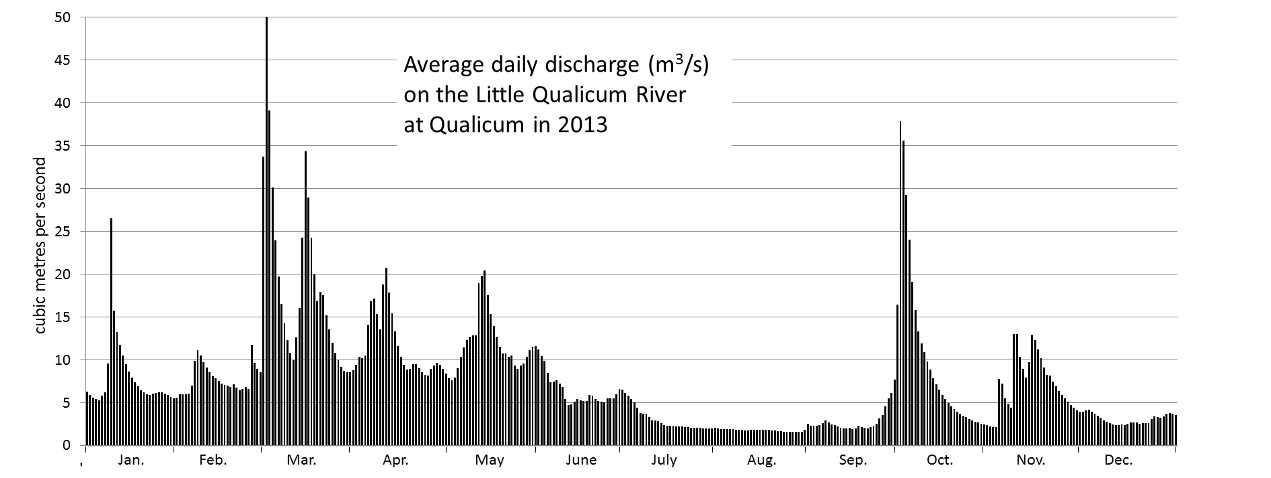

Streams in coastal areas of southern British Columbia show a very different pattern from those in most of the rest of the country because their drainage basins do not remain entirely frozen and because they receive a lot of rain (rather than snow) during the winter. The Qualicum River on Vancouver Island typically has its highest discharge levels in January or February and its lowest levels in late summer (Figure 7.5.2). In 2013, the minimum discharge was 1.6 m3/s, in August, and the maximum was 34 times higher, 53 m3/s, in March.

When a stream’s discharge increases, both the water level (stage) and the velocity increase as well. Rapidly flowing streams become muddy and large volumes of sediment are transported both in suspension and along the stream bed. In extreme situations, the water level reaches the top of the stream’s banks (the bank-full stage, see Figure 7.4.4), and if it rises any more, it floods the surrounding terrain. In the case of mature or old-age streams, this could include a vast area of relatively flat ground known as a flood plain, which is the area that is typically covered with water during a major flood. Because fine river sediments are deposited on flood plains, they are ideally suited for agriculture and thus are typically occupied by farms and residences, and in many cases, by towns or cities. Such infrastructure is highly vulnerable to damage from flooding, and the people that live and work there are at risk.

Most streams in Canada have the greatest risk of flooding in the late spring and early summer when stream discharges rise in response to melting snow. In some cases, this is exacerbated by spring storms. In years when melting is especially fast and/or spring storms are particularly intense, flooding can be very severe.

One of the worst floods in Canadian history took place in the Fraser Valley in late May and early June of 1948. The early spring of that year had been cold, and a large snow pack in the interior was slow to melt. In mid-May, temperatures rose quickly and melting was accelerated by rainfall. Fraser River discharge levels rose rapidly over several days during late May, and the dykes built to protect the valley were breached in a dozen places. Approximately one-third of the flood plain was inundated and many homes and other buildings were destroyed, but there were no deaths. The Fraser River flood of 1948, which was the highest in the past century, was followed by very high river levels in 1950 and 1972 and by relatively high levels several times since then, the most recent being 2007 (Table 7.5.1). In the years following 1948, millions of dollars were spent repairing and raising the existing dykes and building new ones; since then damage from flooding in the Fraser Valley has been relatively limited.

| Rank | Year | Month | Date | Stage (metres) | Discharge (cubic metres per second) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1948 | May | 31 | 11.0 | 15,200 |

| 2 | 1972 | June | 16 | 10.1 | 12,900 |

| 3 | 1950 | June | 20 | 9.9 | 12,500 |

| 4 | 1964 | June | 21 | 9.6 | 11,600 |

| 5 | 1997 | June | 5 | 9.5 | 11,300 |

| 6 | 1955 | June | 29 | 9.4 | 11,300 |

| 7 | 1999 | June | 22 | 9.4 | 11,000 |

| 8 | 2007 | June | 10 | 9.3 | 10,850 |

| 9 | 1974 | June | 22 | 9.3 | 10,800 |

| 10 | 2002 | June | 21 | 9.2 | 10,600 |

Serious flooding happened in July 1996 in the Saguenay-Lac St. Jean region of Quebec. In this case, the floods were caused by two weeks of heavy rainfall followed by one day of exceptional rainfall. July 19 saw 270 millimetres of rain, equivalent to the region’s normal rainfall for the entire month of July. Ten deaths were attributed to the Saguenay floods, and the economic toll was estimated at $1.5 billion.

Just a year after the Saguenay floods, the Red River in Minnesota, North Dakota, and Manitoba reached its highest level since 1826. As is typical for the Red River, the 1997 flooding was due to rapid snowmelt. Because of the south-to-north flow of the river, the flooding starts in Minnesota and North Dakota, where melting starts earlier and builds toward the north. The residents of Manitoba had plenty of warning that the 1997 flood was coming because there was severe flooding at several locations on the U.S. side of the border.

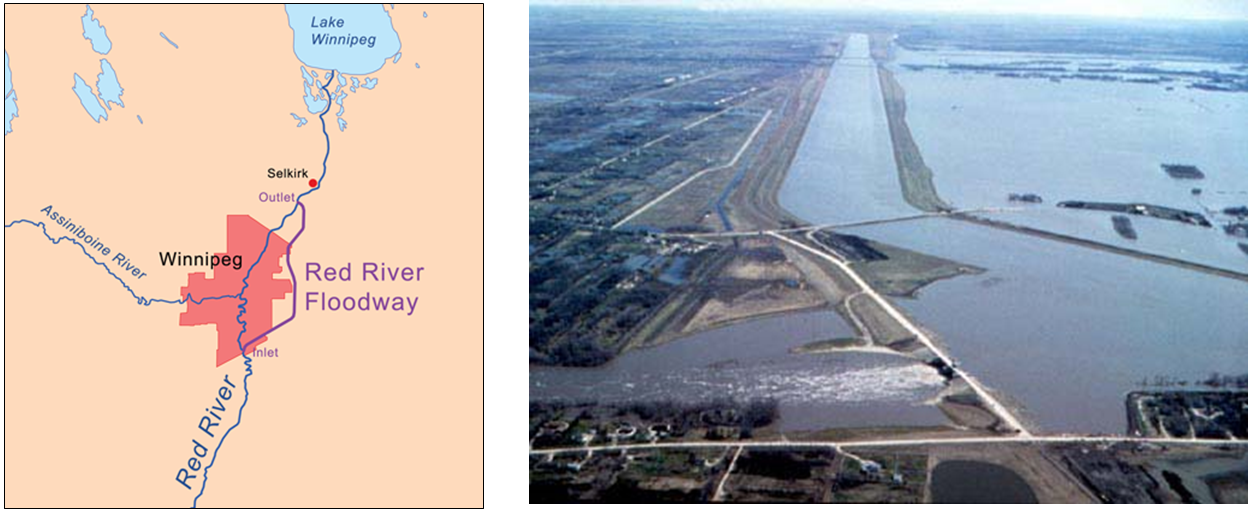

After the 1950 Red River flood, the Manitoba government built a channel around the city of Winnipeg to reduce the potential of flooding in the city (Figure 7.5.3). Known as the Red River Floodway, the channel was completed in 1964 at a cost of $63 million. Since then it has been used many times to alleviate flooding in Winnipeg and is estimated to have saved many billions of dollars in flood damage. The massive 1997 flood was almost too much for the floodway; in fact, the amount of water diverted was greater than the designed capacity. The floodway has recently been expanded so that it can be used to divert more of the Red River’s flow away from Winnipeg.

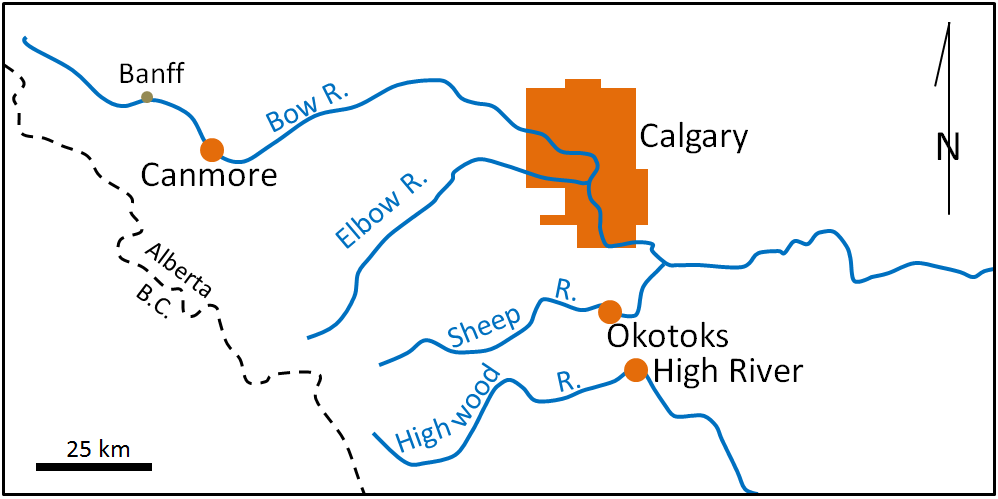

Canada’s most costly flood ever was the June 2013 flood in southern Alberta. The flooding was initiated by snowmelt and worsened by heavy rains in the Rockies due to an anomalous flow of moist air from the Pacific and the Caribbean. At Canmore, rainfall amounts exceeded 200 millimetres in 36 hours, and at High River, 325 millimetres of rain fell in 48 hours.

In late June and early July, the discharges of several rivers in the area, including the Bow River in Banff, Canmore, and Exshaw, the Bow and Elbow Rivers in Calgary, the Sheep River in Okotoks, and the Highwood River in High River, reached levels that were 5 to 10 times higher than normal for the time of year (see Exercise 7.5.5). Large areas of Calgary, Okotoks, and High River were flooded and five people died (see Figures 7.5.2 and 7.5.3). The cost of the 2013 flood is estimated to be approximately $5 billion. Learn more about Alberta’s flood of the century.

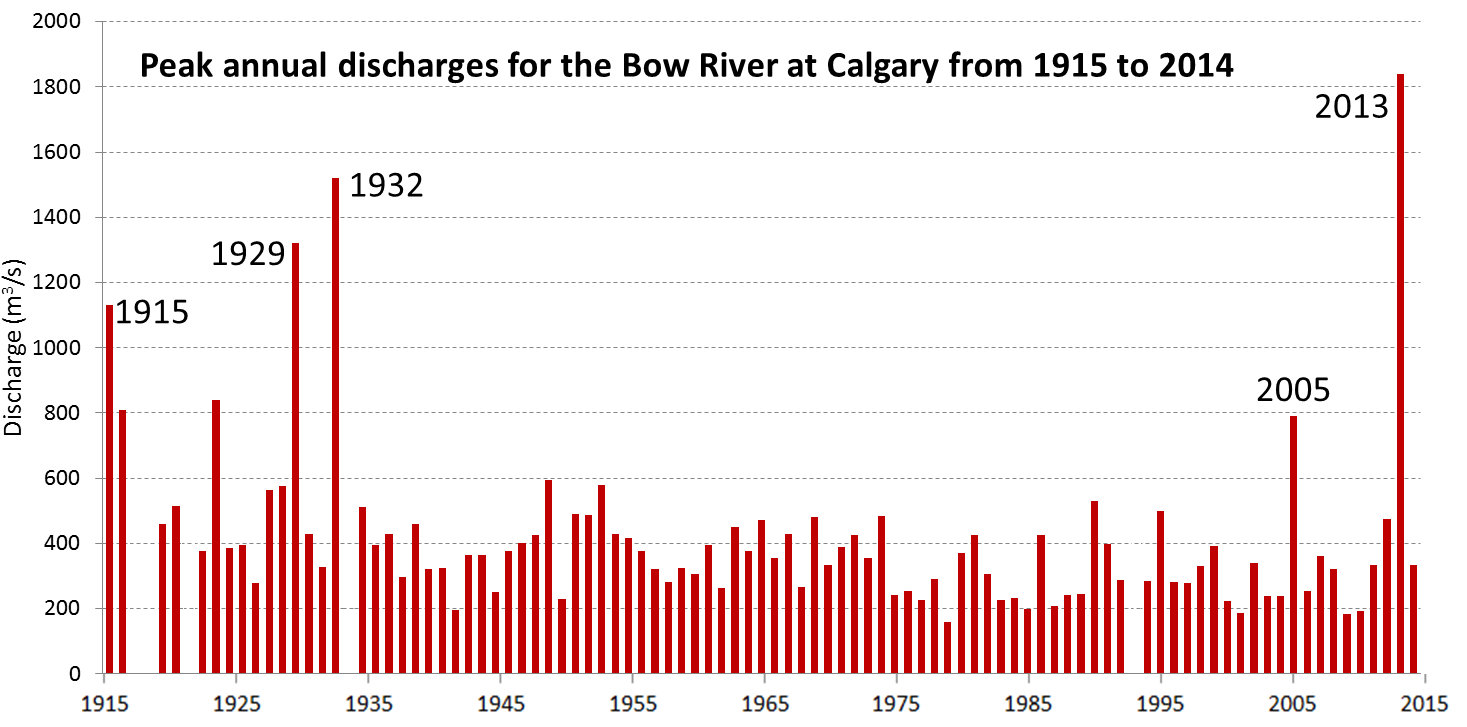

Figure 7.5.6 shows the highest discharges per year between 1915 and 2014 on the Bow River at Calgary. Using this data set, we can calculate the recurrence interval (Ri) for any particular flood magnitude using the equation: Ri = (n+1)/r (where n is the number of floods in the record being considered, and r is the rank of the particular flood). There are a few years missing in this record, and the actual number of data points is 95. The largest flood recorded on the Bow River over that period was the one in 2013, 1,840 cubic metres per second (m3/s) on June 21. Ri for that flood is (95+1)/1 = 96 years. The probability of such a flood in any future year is 1/Ri, which is 1%. The fifth-largest flood was just a few years earlier in 2005, at 791 m3/s. Ri for that flood is (95+1)/5 = 19.2 years. The recurrence probability is 5%.

- Calculate the recurrence interval for the second-largest flood (1932, 1,520 m3/s).

- What is the probability that a flood of 1,520 m3/s will happen next year?

- Examine the 100-year trend for floods on the Bow River. If you ignore the major floods (the labelled ones), what is the general trend of peak discharges over that time?

One of the things that the 2013 flood on the Bow River teaches us is that we can’t predict when a flood will occur or how big it will be, so in order to minimize damage and casualties we need to be prepared. Some of the ways of doing that are as follows:

- Mapping flood plains and not building within them

- Building dykes or dams where necessary

- Monitoring the winter snowpack, the weather, and stream discharges

- Creating emergency plans

- Educating the public

Image Descriptions

Media Attributions

- Figure 7.5.1: © Steven Earle. CC BY. Based on from data at Water Survey of Canada, Environment Canada.

- Figure 7.5.2: © Steven Earle. CC BY. Based on from data at Water Survey of Canada, Environment Canada.

- Figure 7.5.3: Left image: “Rednorthfloodwaymap” © Kmusser. CC BY-SA. Right image: From Natural Resources Canada 2012, courtesy of the Geological Survey of Canada (Photo 2000-118 by G.R. Brooks).

- Figure 7.5.4: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 7.5.5: “Riverfront Ave Calgary Flood” © Ryan L. C. Quan. CC BY-SA. “Okotoks – June 20, 2013 – Flood waters in local campground playground-03” © Stephanie N. Jones. CC BY-SA.

- Figure 7.5.6: © Steven Earle. CC BY. Based on data from Water Surveys of Canada, Environment Canada.

- Mannerström, M, 2008, Comprehensive Review of Fraser River at Hope Flood Hydrology and Flows Scoping Study, Report prepared for the B.C. Ministry of the Environment [PDF]. Available at: http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wsd/public_safety/flood/pdfs_word/review_fraser_flood_flows_hope.pdf ↵