4.5 Volcanic Hazards

Steven Earle and Laura J. Brown

There are two classes of volcanic hazards, direct and indirect. Direct hazards are forces that directly kill or injure people or destroy property or wildlife habitat. Indirect hazards are volcanism-induced environmental changes that lead to distress, famine, or habitat degradation. It is estimated that indirect effects of volcanism have accounted for approximately 8 million deaths during historical times, while direct effects have accounted for fewer than 200,000, or 2.5% of the total. Some of the more important types of volcanic hazards are summarized in Table 4.4.1.

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Type | Description | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Tephra emissions | Small particles of volcanic rock emitted into the atmosphere |

|

| Gas emissions | The emission of gases before, during, and after an eruption |

|

| Pyroclastic density current | A very hot (several 100°C) mixtures of gases and volcanic fragments (tephra) that flows rapidly (up to 100s of kilometres per hour (km/h)) down the side of a volcano | Extreme hazard — destroys anything in the way |

| Pyroclastic fall | Vertical fall of tephra in the area surrounding an eruption |

|

| Lahar | A flow of mud and debris down a channel leading away from a volcano, triggered either by an eruption or a severe rain event | Severe risk of destruction for anything within the channel—lahar mudflows can move at 10s of km/h |

| Sector collapse/ debris avalanche | The failure of part of a volcano, either due to an eruption or for some other reason, leads to the failure of a large portion of the volcano | Severe risk of destruction for anything in the path of the debris avalanche |

| Lava flow | The flow of lava away from a volcanic vent | People and infrastructure are at risk, but lava flows tend to be slow (less than km/h) and are relatively easy to avoid |

Volcanic Gas and Tephra Emissions

Large volumes of tephra (rock fragments, mostly pumice) and gases are emitted during major Plinian eruptions (large explosive eruptions with hot gas and tephra columns extending into the stratosphere) at composite volcanoes; a large volume of gas is released during some very high-volume effusive eruptions. One major effect is cooling the climate by 1° to 2°C for several months to a few years because the dust particles and tiny droplets and particles of sulphur compounds block the sun. The last significant event of this type was in 1991 and 1992, following the large eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. A temperature decrease of 1° to 2°C may not seem like very much, but that is the global average amount of cooling, and cooling was much more severe in some regions and at some times.

Over an eight-month period in 1783 and 1784, a massive effusive eruption occurred at the Laki volcano in Iceland. Although relatively little volcanic ash was involved, a massive amount of sulphur dioxide was released into the atmosphere, along with a significant volume of hydrofluoric acid (HF). The sulphate aerosols that formed in the atmosphere led to dramatic cooling in the northern hemisphere. There were serious crop failures in Europe and North America, and a total of 6 million people are estimated to have died from famine and respiratory complications. In Iceland, poisoning from HF resulted in the death of 80% of sheep, and 50% of cattle, and the ensuing famine, along with HF poisoning, resulted in more than 10,000 human deaths—about 25% of the population.

Volcanic ash can also seriously affect aircraft because it can destroy jet engines. For example, over 5 million airline passengers were disrupted by the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption in Iceland.

Pyroclastic Density Currents

In a typical explosive eruption at a composite volcano, the tephra and gases are ejected with explosive force and are hot enough to be forced high up into the atmosphere. As the eruption proceeds and the amount of gas in the rising magma starts to decrease, parts will become heavier than air, and they can then flow downward along the volcano’s flanks (Figure 4.27). As they descend, they cool more and flow faster, reaching speeds up to several hundred kilometres per hour. A pyroclastic density current (PDC) consists of tephra ranging in size from boulders to microscopic shards of glass (made up of the edges and junctions of the bubbles of shattered pumice), plus gases (dominated by water vapour but also including other gases). The temperature of this material can be as high as 1000°C. Among the most famous PDCs is the one that destroyed Pompeii in the year 79 CE, killing an estimated 18,000 people, and the one that destroyed the town of St. Pierre, Martinique, in 1902, killing an estimated 30,000.

The buoyant upper parts of pyroclastic density currents can flow over water, sometimes for several kilometres. The 1902 St. Pierre PDC flowed out into the city’s harbour and destroyed several wooden ships anchored there.

Pyroclastic Fall

Most of the tephra from an explosive eruption ascends high into the atmosphere, and some of it is distributed around Earth by high-altitude winds. The larger components (larger than 0.1 mm) tend to fall relatively close to the volcano, and the amount produced by large eruptions can cause serious damage and casualties. The large 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines resulted in the accumulation of tens of centimetres of ash in fields and on rooftops in the surrounding populated region. Heavy typhoon rains that hit the island added to the tephra’s weight, leading to the collapse of thousands of roofs and at least 300 of the 700 deaths attributed to the eruption.

Lahar

A lahar is any mudflow or debris flow that is related to a volcano. Most are caused by melting snow and ice during an eruption, as was the case with the lahar that destroyed the Colombian town of Armero in 1985. Lahars can also happen when there is no volcanic eruption, and one of the reasons is that, as we’ve seen, composite volcanoes tend to be weak and easily eroded.

In October 1998, Mitch ( a category 5 hurricane) slammed into the coast of Central America. Damage was extensive, and 19,000 people died, not so much because of high winds but because of intense rainfall—some regions received almost 2 m of rain over a few days! Mudflows and debris flows occurred in many areas, especially in Honduras and Nicaragua. An example is at the Casita Volcano in Nicaragua, where the heavy rains weakened rock and volcanic debris on the upper slopes, resulting in a debris flow that rapidly grew in volume as it raced down the steep slope and then ripped through the towns of El Porvenir and Rolando Rodriguez killing more than 2,000 people (Figure 4.28). El Porvenir and Rolando Rodriguez were new towns built without planning approval in an area known to be at risk of lahars.

Sector Collapse and Debris Avalanche

In the context of volcanoes, sector collapse or flank collapse is the catastrophic failure of a significant part of an existing volcano, creating a large debris avalanche. This hazard was first recognized with the failure of the north side of Mount St. Helens immediately before the large eruption on May 18, 1980. In the weeks before the eruption, a large bulge had formed on the side of the volcano, the result of magma transfer from depth into a satellite magma body within the mountain itself. Early on the morning of May 18, a moderate earthquake struck nearby; this is thought to have destabilized the bulge, leading to Earth’s largest observed slope failure. The failure of this part of the volcano exposed the underlying satellite magma chamber, causing it to explode sideways, which then exposed the conduit leading to the magma chamber below. The resulting Plinian eruption lasted for nine hours with a 24-kilometre high eruption column.

In August 2010, a massive part of the flank of B.C.’s Mount Meager gave way, and about 48 million cubic metres (m3) of rock rushed down the valley, one of Canada’s largest slope failures in historical times (Figure 4.29). More than 25 slope failures have occurred at Mount Meager in the past 8,000 years, some more than 10 times larger than the 2010 failure.

Lava Flows

As we saw in Exercise 4.4, lava flows at volcanoes like Kilauea do not advance very quickly; in most cases, people can get out of the way. Of course, it is more difficult to move infrastructure, and so buildings and roads are typically the main casualties of lava flows.

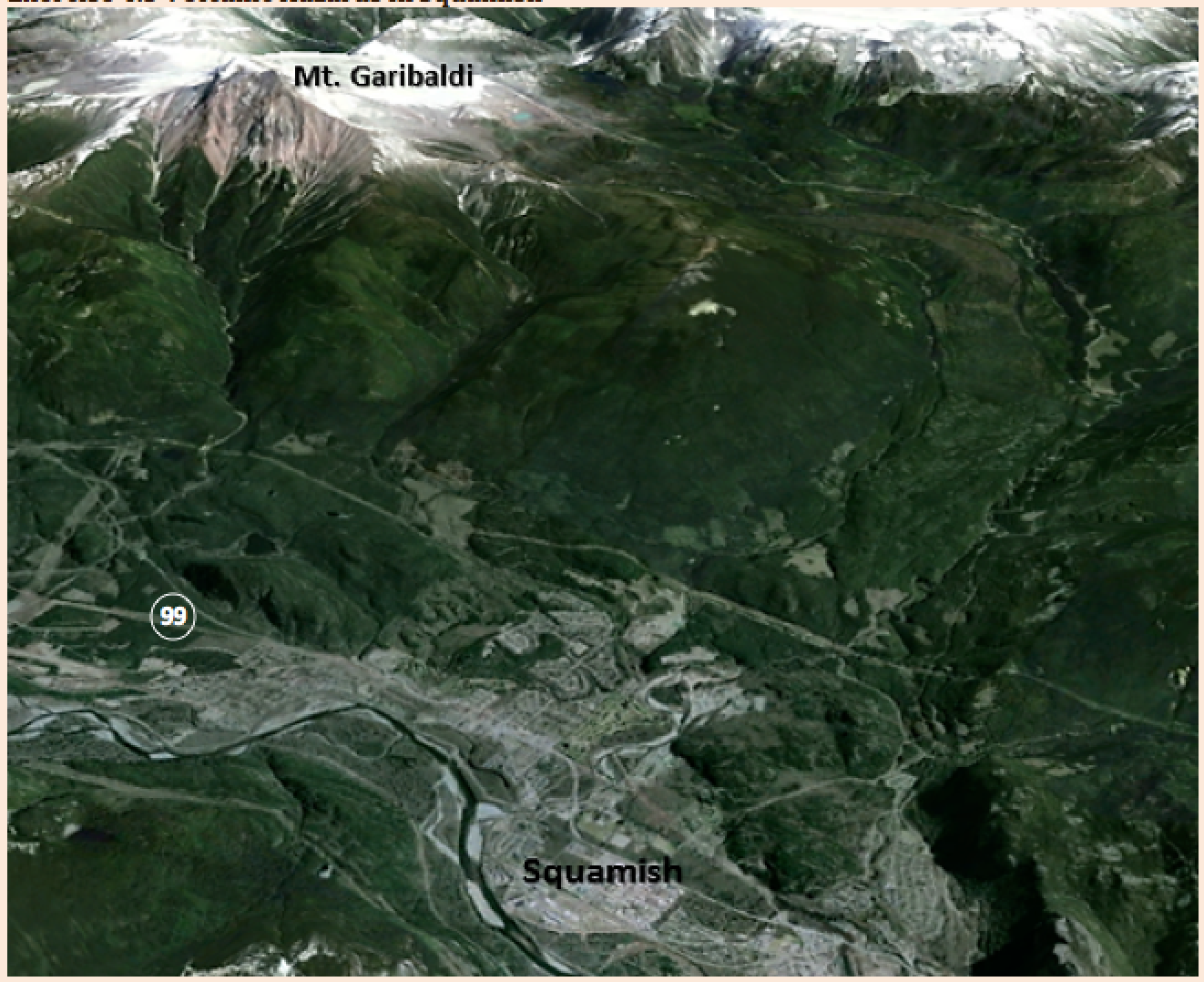

Exercise 4.5 Volcanic hazards in Squamish

The town of Squamish is approximately 10 km from Mount Garibaldi, as shown in the photo. If Mount Garibaldi were to erupt, which of the following hazards could be an issue for people in and around Squamish? Explain why or why not.

- Tephra emission.

- Gas emission.

- Pyroclastic density current.

- Pyroclastic fall.

- Lahar.

- Sector collapse.

- Lava flow.

Media Attributions

- Figure 4.27: “Pyroclastic flows at Mayon Volcano” by USGS. Public domain.

- Figure 4.28: “Casita Volcano” by USGS. Public domain.

- Figure 4.29: August 2010 Mt. Meager landslide, BC © Mika McKinnon. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

- Figure 4.30: Screenshot from Google Earth. © Google. Modified by Steve Earle. Used with permission.