6 Workshop 6 – Leadathon 2023: Weaving Indigenous Ways of Knowing into the Canadian Engineering Grand Challenges

University of Guelph; University of Manitoba; and University of Waterloo

INTRODUCTION

This workshop will cover Indigenous Ways of Knowing in Engineering, and the benefits of “Two-Eyed Seeing” in relation to obstacles such as the Canadian Engineering Grand Challenges (CEGCs). Though this workshop was constructed utilizing many sources of research and expertise, it should be noted that this topic is complex and fairly new, and that the leads responsibile for creating this workshop are not experts themselves. Like those of you participating in this workshop, we are all on a journey of lifelong leadership learning, and wish to do our best to understand and properly represent the views presented today, to better relate to and utilize Indigenous Ways of Knowing in Engineering.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

This workshop will cover our Relationship with the Land, our Relationship with the Community, Indigenous Creation, and the Canadian Engineering Grand Challenges (CEGCs). These topics will be related to their Western counterparts, and largely take place in the Societal sphere of the leadership domains. The problems we face in engineering affect not just engineers, but all of society. By incorporating the viewpoints of different groups, and being especially mindful of minorities, we as engineers can better provide potential solutions to these issues.

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE LAND

Relationship with the Land, as the name implies, deals largely with how we interact with and treat the environment around us. As such, its Western counterpart would be the topic of sustainability. Sustainability is a common topic in all levels of education, and includes ideas such as the three R’s, or climate change, but we’ve probably come at all of these topics from a certain perspective.

Western Views

We’ve all probably been exposed to sustainability from the viewpoint of ensuring the well-being of human societies and communities. Making sure that we, as humans, have a future on this earth. We’ve also been taught these topics in ways that reflect our objectification of nature, and the separation between human civilization and nature. The major point of concern in these discussions is usually what can nature do for us, and what can it continue to do for us going forward. This involves thought processes such as, how can we best exploit the resources available to us.

Indigenous Views

Indigenous communities, on the other hand, approach the very same topics from a different perspective. While Western views on sustainability are focused on what nature can do for us, perhaps the question we should really be asking is, what can we do for nature. Indigenous views on sustainability include ensuring the overall well-being of Mother Earth. As humans, we might be good at gathering resources and making them more useful to us, but at the end of the day we’re just a fraction of all life on the planet. Indigenous views recognize that all things on earth are connected, and our actions have consequences even if we don’t intend them to. As such influential beings on this planet, we have a responsibility to not only take from the earth, but also take care of the earth from a place of respect and reciprocity. At the end of the day, the better off the planet is, the better off we are, and thus we should care greatly about our relationship with the land.

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE LAND PRINCIPLES

1 – Land-Based Learning

And at the fundamentals of having a relationship with the land, we must understand the land, not from our perspective, but from the earth’s. Land-based learning is the primary way that Indigenous communities learn about and connect with the land, and for generations, Indigenous knowledge has been passed down through the land. The land is the first teacher, and it creates spiritual and physical relationships for Indigenous communities.

The core concept behind Land-based learning is learning how to properly use and maintain a relationship with the local land you live on. In Indigenous communities, this involves Elders and users of the land taking the next generations outside, to be immersed in nature and to interact with the earth. They learn how to not only sustain themselves and their communities through foraging, hunting, fishing, farming, and other practices, but also how to sustain the land for future use.

2 – Seven Generations Principle

The involvement of younger individuals is crucial in Land-Based Learning, and brings us into our next major topic, the Seven Generations Principle.The Seven Generations Principle is based on Haudenosaunee philosophy. It is the idea that a person’s impact lasts for seven generations. Your current world and the way you interact with it, was impacted by those seven generations before you, and whatever you choose to do with your time on this earth will impact those in the future for seven generations to come. This principle is the basis of the lifestyle that many Indigenous communities follow, inspiring interconnectedness across the past, present, and future.

To summarize, engineers who focus on sustainability are missing this important principle of Seven Generations. There is no guideline that engineers must follow when deciding how far into the future something must last for it to be sustainable, however, the Seven Generations Principle creates that lifespan. While human livelihood is based on resource gathering and use, we must ensure that our actions are not destructive. The land must be viable and healthy for seven generations into the future.

3 – Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Putting the concepts of Land-based Learning and The Seven Generations Principle together, we get a flow of information and culture from one generation to the next. Thus, we arrive at the concept of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. This is an accumulation of knowledge over generations by those who live on the land and rely on the land for their well-being. Rather than what the engineering discipline is used to, Traditional Ecological Knowledge is culturally and spiritually based, in contrast to being quantitative and calculative. It relies on having a strong connection and relationship with the land, and is centered around nature, and obtaining knowledge by using the whole of our senses in direct participation with the natural world.

This experience of obtaining Traditional Ecological Knowledge has led us into topics such as Indigenous cultures, and spirituality. Thus, to properly continue our conversation about sustainability, it is important to look at not only the land, but also to the communities who have these concepts of sustainability embedded into their cultures, practices, and spirits.

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE COMMUNITY

While it may be difficult to find an exact parallel for this, it is perhaps best described as the concept of Leadership. When trying to relate to others, to understand or to problem solve, we often must facilitate communication and interaction. This act of relating to the community of people around you, or even other communities, can thus be related to being one who facilitates discussions and interactions, aka a Leader.

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE COMMUNITY PRINCIPLES

4 – Sharing Circles

We’ve previously mentioned that information gets shared between individuals and generations about sustainability. You can probably imagine that sometimes issues regarding sustainability might also appear in these discussions. Thus, many communities would use the traditional method of Sharing Circles, Talking Circles, or Circle Talks, to discuss and resolve these issues. These Sharing Circles are highly effective and widely applicable, making them a great tool for communities to facilitate open discussions, conflict resolution and to discuss any issues of importance.

In practice, using a sharing circle consists of people gathered in a circle taking turns in sharing their opinions one at a time without interruption. A Circle Keeper, whose role is to facilitate the Sharing Circle, performs the act of opening the circle with a prayer and Smudging. The conversation typically starts with a participant receiving a Talking Piece, which is an object to identify the primary speaker. This usually takes the form of a feather, talking stick, or stone, and is passed along between participants once they’re done speaking. It is important that whoever has the Talking Piece is allowed to speak for as long as they desire, and by the end of the circle, every participant will have shared their wisdom and experiences on the topic of discussion.

Circles have strong significance in Indigenous cultures, representing continuity, equity, and life. These characteristics are significant in the concept of Sharing Circles, as everyone involved can freely speak their mind, taking turns sharing until everyone has participated. In contrast, Western meetings will generally rely on some form of hierarchy, with leaders prompting members to speak. Sharing Circles, on the other hand, allow for more freely flowing discussions without fear of judgement from a boss or leader, encouraging everyone to actively participate and listen.

ACTIVITY 1: VISUALIZATION

The objective of this activity is to visualize Indigenous Ways of Knowing through Images. You may do this activity alone, but it can be beneficial to have multiple perspectives, so a team is recommended. You will be making a single PowerPoint slide expressing your views on Indigenous Ways of knowing, conveying your feelings through an image and a brief description. Follow the steps provided below to participate:

- Think of the concepts that have been presented on the ‘Relationship with the Land’ and ‘Relationship with Community’ reflecting on what they mean to you and your team.

- Select a Creative Commons image that represents any one of the Indigenous Ways of Knowing concepts within ‘Relationship with the Land’ or ‘Relationship with Community.’

- Describe the image and Indigenous Ways of Knowing concept that the image represents in no more than 120 words.

- Add a creative title to your slide that would indicate some reference to the image selected and the Indigenous Ways of Knowing concept.

Activity 1 Template:

- Google Drive: Link to template

CREATION (INDIGENOUS DESIGN)

The Design Process generally presented in Canadian engineering schools today refers to a series of steps taken in the development of a design/process. These steps, while being a very helpful process to follow to minimize risk and streamline productivity, are not the definitive approach to creating something. Inventions were being made long before they were even called inventions, and thus there exist many different methodologies to creating things. Similarly, Indigenous communities have been making things for centuries, and they too have steps they follow to achieve the best results.

Western Views

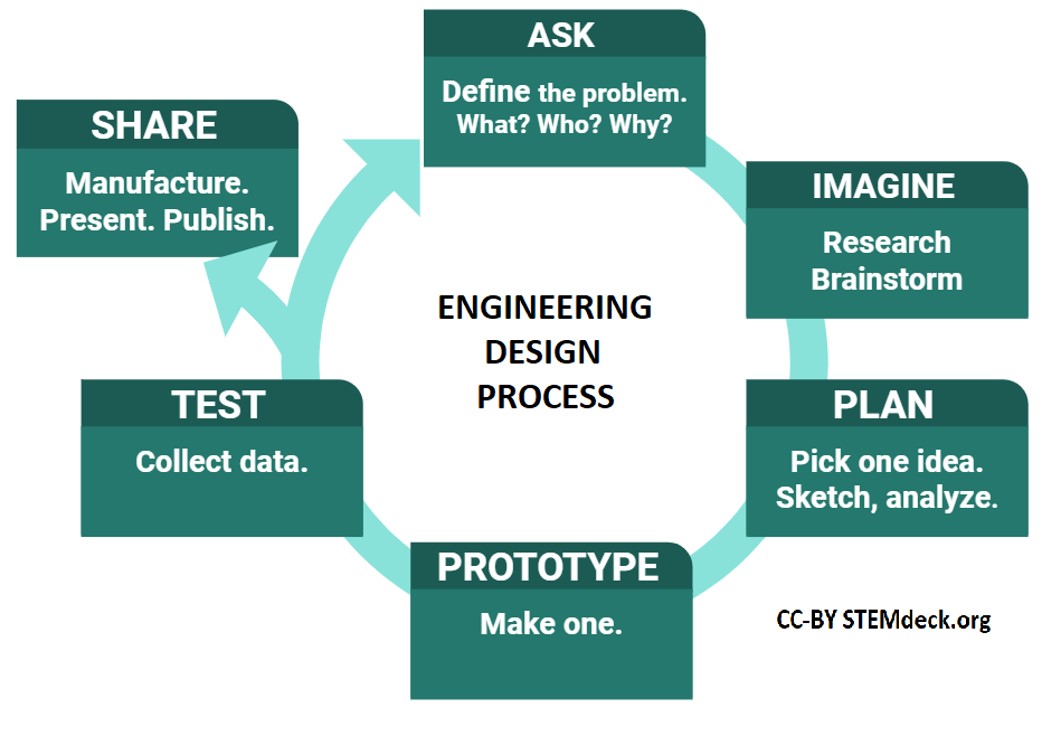

The typical western design process is usually an iterative cycle following a few basic steps. The first step usually involves assessing the problem, and trying to outline all the criteria. Once the problem has been adequately analyzed, we can begin to do some research for potential solutions. A plan can then be made to follow one of the concepts from the research phase, based on the importance of specific criteria the solution needs to achieve. The plan can then be followed to obtain a prototype which can be tested. The results of this test start the cycle anew, giving the engineers things to improve upon.

Indigenous Views

Indigenous Creation is vital to the history of Indigenous communities, and the history of Canada overall. The entire design process is very wholistic in nature and puts heavy emphasis on a healthy relationship with the land and the community. It has provided us with years of inventions and methodologies that have been used throughout the ages, and even into modern day. The use of locally sourced materials help both a sustainability factor but also tailoring a specific problem in a community towards its own unique solution, leading to more introspection on the problem itself. We should also look to nature, just as Indigenous Peoples have been doing for hundreds of years, for improvements in connectivity and sustainability. It is important to consider the significance of the design, whether it be for a tool or a building, and we should understand how people will view and interact with it.

CREATION PRINCIPLES

5 – Inspiration from Nature

Indigenous Peoples have a strong relationship with the land and nature and use this relationship to inspire their designs through shape, function, and material selection. Indigenous creations inspired by nature include snowshoes (inspired by the shape of animal feet) and the Birch Bark Canoe (inspired by the trees and the shape of the human body). In the Western world, using nature for design inspiration is known scientifically as Biomimicry.

Another notable example of modern-day Indigenous architecture includes University of Manitoba’s Indigenous Student Centre, or Migizii Agamik (Bald Eagle Lodge). This building was designed by a large team of people, inclusive of Indigenous Elders, student representatives and Indigenous alumni. Staying true to Indigenous beliefs, the building is organized into four main components using the four cardinal directions. This building also features a locally-quarried, tyndall stone wall that traverses the true east-west axis, providing guidance and orientation to individuals in accordance to the path of the sun, rising from the East and returning to the earth in the west.

6 – Two-Eyed Seeing

Two-Eyed Seeing incorporates the benefits of both Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Western Ways of Knowing to create designs that achieve functional requirements while cultivating a symbiotic relationship with the land and the community of users today and into the future. It provides a solution that incorporates the best of both worlds.

One example of Two-Eyed seeing we see today is OldTribes. OldTribes is an Edmonton based company which is known for its Indigenous influence and support of local artisans. They feature unique, handmade wool products such as alpaca wool blankets and jackets. They also incorporate traditional beadwork and embroidery techniques into their products, blending modern processes with traditional methodologies.

CANADIAN ENGINEERING GRAND CHALLENGES

The Canadian Engineering Grand Challenges (CEGCs) were created by the Engineering Deans Canada Council in response to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) created by the United Nations (UN).

The Canadian Engineering Grand Challenges (CEGCs) were created by the Engineering Deans Canada Council in response to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) created by the United Nations (UN).

There are 6 CEGCs, as seen above, and they entail the following challenges:

Resilient Infrastructure – Surprisingly much of Canada’s infrastructure is in very poor condition and is at risk from various disasters and climate change.

Affordable and Sustainable Energy – Many rural communities and minorities lack sufficient power, and even more communities lack green energy.

Safe Water – Water is often taken for granted daily, but many communities lack safe water to drink, shower, or do anything with.

Safe and Sustainable Cities – The designs of cities often negatively impact minorities. Safety and sustainability must be prioritized when designing, developing and maintaining cities.

Sustainable Industrialization – Industrialization is important to the economy and our daily lives. We must find methods to obtain and process resources without harming people or the environment.

Inclusive STEM Education – Increasing diversity in faculty and students will result in more perspectives involved in many fields, resulting in a more equitable society.

ACTIVITY 2: WEAVING INDIGENOUS WAYS OF KNOWING INTO THE CEGCS

The objective of this activity is to Weave Indigenous Ways of Knowing into the Canadian Engineering Grand Challenges by defining a problem statement that represents the Canadian Engineering Grand Challenge in the Indigenous Community while exploring ways to engage with the community to understand their needs using concepts of Indigenous Ways of Knowing. The output of the first activity may be beneficial to you in this activity, and more details on how to accomplish this objective can be found below:

Step 1:

- Review the Indigenous Community case study to understand the nature of the challenge in this community.

- Explore what you need to learn about the selected Indigenous Community before you would engage with them to address their challenge.

- As an engineering team, define the problem in the community. Your role will be to define a problem statement including the scope of the problem and the community needs. Your role will not be to formulate a solution.

- Consider Indigenous Ways of Knowing when defining the problem and understanding the needs of the community.

- Think of the concepts that have been presented on the ‘Relationship with the Land,’ ‘Relationship with Community,’ and ‘Creation’ reflecting on what resonates with the team.

Step 2:

- Select ONLY 2 of the 6 concepts of Indigenous Ways of Knowing to describe points for consideration when engaging with the community.

- Select a Creative Commons image that represents any one of the Indigenous Ways of Knowing concepts within ‘Relationship with the Land,’ ‘Relationship with Community,’ or Creation.’

- Add a creative title to your slide that would indicate some reference to the challenge and any of the selected Indigenous Ways of Knowing concepts.

Activity 2 Resources:

- Google Drive: Link to more instructions

- Google Drive: Link to template

WORKSHOP KEY TAKEAWAYS

Understanding Indigenous Ways of Knowing in engineering can be helpful in building solutions that acknowledge a wide range of perspectivies. This increases inclusivity, and also utilizes Two-Eyed seeing to obtain a solution that considers much more than a single viewpoint could. These perspectives will surely be beneficial in our approach to any obstacles faced in this field, and hopefully will provide some solutions to the Canadian Engineering Grand Challenges.

RESOURCES

Click here to access the workshop worksheets.