3 Transport Networks in Later Medieval Scotland: Routes, Roads, and Justice Ayres

Hector L. MacQueen

[1] Transport and communication networks were of crucial importance in medieval Scotland but have not yet received the attention they deserve.[2] As Grant Simpson once remarked, “routes obviously link places which early travellers were anxious to reach: human decisions lie behind their creation.”[3] Pilgrimage routes are an excellent example,[4] while military movements within the country make it apparent that at least some routes were roads capable of taking wheeled traffic. Further, as Elizabeth Ewan has observed, “a wide-ranging network of roads between burghs, along which traders could bring their wagons and packhorses” was how burgesses could profitably exploit their freedom from toll across the kingdom.[5] She cited the work of Geoffrey Barrow, who had previously drawn attention to the existence of roads linking burghs and described as royal or public.[6] Royal roads must have been important for the operations of royal government. In this chapter, the evidence for the routes taken by royal justice ayres, central to the administration of civil and criminal justice, is assessed, and it is argued that they provide further good, if indirect, evidence for a transport network of roads at least in the eastern and southern parts of the kingdom.

Ayres required the movement of the king’s justiciars and their entourages on two circuits north and south of the River Forth, holding successive courts at the head burghs of each sheriffdom in those areas. There was also the sending to and fro of communications with the ayre’s next port of call, as well as ongoing reports to, and messages from, ‘central’ government (although not infrequently the ayre was accompanied by the king and his council).[7] Popular perceptions of the ayre as a burden on the country through which it passed may be sensed from the 1450 statute requiring justiciars and others to “ryde bot competent and esy nowmir to eschew grevans and hurting of the puple.”[8] Unfortunately no evidence exists as to the numbers travelling with the justiciar. His entourage probably included deputies, counsellors, assessors, clerks and other officials, and, perhaps, attendant baggage carts. The problem was, therefore, most likely the ayre’s demands for accommodation, sustenance and, perhaps, a regular supply of fresh horses. The system could not have worked without at least adequate transport and communication links between the burghs involved, not only for the office-holders, but also would-be litigants.

In theory, the ayres occurred twice a year, in the spring and the autumn.[9] In the past, historians doubted whether practice followed theory. Professor Dickinson observed, for example, that “a system which works well has no need of frequent legislation, but at least seven acts enjoining the ayres to be held yearly, or generally, or diligently were passed between 1458 and 1488.”[10] But, as I have endeavoured to show elsewhere, the legislation referred to by Dickinson is capable of other readings: in particular, as signifying that justice ayres were “part of the ordinary routine of royal government, … an aspect of normality, rather thanoccasional events.”[11] The several acts passed in the reign of James III (1460–88) may indicate some lack of ayres in the 1480s, but more probably reflect parliamentary concern to have convicted criminals punished rather than given royal remissions.[12] The first aim of this paper, therefore, is to show detailed evidence that the later medieval justice ayre was indeed a much more regular event than past scholarship tended to assume.

The material for such an investigation is not extensive since we lack any justiciary records until the end of the fifteenth century. What follows is largely based on an examination of the financial record contained in the exchequer rolls and treasurer’s accounts, and on the completely haphazard references preserved in various other sources. The limitations of such evidence for the purpose of determining the frequency of the justice ayres are obvious. The exchequer rolls refer to justice ayres when recorded in sheriffs’ accounts, but it is notorious that there are serious gaps in the sheriffs’ accounts.[13] References to the ayres in the treasurer’s accounts are more or less completely dependent on the king’s personal expenditure or engagement with an ayre, which was not invariable.[14] Equally, a complete assessment of the ‘charter’ evidence would, in Professor Barrow’s words, “require the laborious and minute examination of scores and hundreds of private charters.”[15] The present study has not aimed at that kind of completeness but rather at the assembly of sufficient material to support the contention that justice ayres were held on a reasonably regular basis throughout the later medieval period. It is then possible to go on to a further conclusion, that this regularity and continuity is good, if indirect, evidence for the later medieval road system and the major routeways in Scotland south of Forth and through the country’s northeastern littoral from the Firth of Forth up to Inverness. The routes followed also suggest the need to use river crossings and ferries, as well as bridges and fords. Speculation about the possible use of sea transport as well in the southwest is offered in at least one instance,[16] although there is no direct evidence for this in any source.

Justice Ayres in the Fourteenth Century

Evidence for the holding of ayres in the reign of Robert I, as distinct from the appointment of justiciars, is scanty but suggestive. The ayres held from 1306 to 1309 were held under English rather than Scottish royal authority.[17] But in 1310 a dispute between the abbot and convent of Lindores and Newburgh was resolved before the northern justiciar, Robert Keith, undoubtedly a Bruce man by that time.[18] The legislation enacted at Scone in 1318 referred to the justiciar’s ayre with the evident expectation that such would be held.[19] There is record of an assize before the justiciar north of Forth in 1320.[20] Perhaps more settled conditions for the holding of ayres south of Forth are indicated by the demand made by the king in 1320 that the abbot and convent of Newbattle should give suit for their lands of Masterton, Mid-Lothian, at the justiciary court of Edinburgh as often as it was held there.[21] The contrast with an exemption in 1315 of Kinloss abbey and its men in Moray from the obligation of suit at any justiciary court, wherever held, should not be overplayed.[22] Other signs that ayres were held include the king’s grants to Robert Lauder the younger; Henry, bishop of Aberdeen; and Melrose abbey of pensions from the issues of the justiciary, respectively, north of Forth, at Aberdeen and Banff, and at Roxburgh,[23] as well as his exemption in 1325 of the tenants of Sir James Douglas from judgment at the hands of the king’s justiciars except in cases of homicide and pleas of the crown.[24] It may safely be concluded that the justice ayres were not permanently dislocated by the turbulent political conditions of the early fourteenth century.

The first mention of ayres after the death of Robert I is a reference in the exchequer rolls for 1331 to “the last ayre at Stirling,”[25] which seems to imply that others had previously been held at that place. But this is the last reference that I have been able to trace to ayres south of Forth until 1346, when, perhaps significantly, David II exempted the abbot and convent of Newbattle from the obligation of suit at the justiciary court of Lothian, which was owed by reason of the grant to them by Robert I of Masterton mentioned in the previous paragraph.[26] There may be more to this than the accidental survival of evidence, for the southeast of Scotland was subject either to English domination or to various acts of devastation, or both, from the mid-1330s until well into the 1350s. Whether or not this actually prevented ayres being held south of Forth, it certainly had its effect on the circuit followed by the southern justiciars, as will be discussed later.[27]

By contrast, in the same period there is a relative abundance of evidence for ayres north of Forth, an area that remained largely under the control of Scottish administration. An ayre was held at Elgin on 10 October 1337,[28] while in late April 1342 a full justice court was held at Inverbervie, Kincardine, by the lieutenants of the northern justiciar.[29] The exchequer rolls for 1343 record the king’s attendance at a justice ayre in Cupar, Fife.[30] While in May 1343 the king had to order the justiciar north of Forth and the sheriff of Perth to pay to Scone abbey its teind of the issues of the justiciary emanating from Gowrie, that still suggests that such issues were being produced.[31] In July 1347, the court of the justice ayre was held at Forfar.[32] There is a further piece of evidence showing us the movements of a northern ayre in February 1348: on the 8th the court was at Forfar and by the 22nd it had moved on to Dundee.[33] In May the following year a court of justiciary was held “at the standing stones of Rayne in Garioch.”[34] It is, however, apparent that there were also problems north of Forth in the 1350s and it has been said that after the departure of David II into English captivity in 1346 “judicial administration was in confusion.”[35] But whether entries in the exchequer rolls such as “the sheriff produced a letter of the earl of Ross, justiciar in his sheriffdom, that he should not intromit with the profits of the justiciary court”[36] mean that ayres were not held must be a matter of doubt.

Upon the king’s return to Scotland in November 1357 he was requested by council general to hold a justice ayre throughout the realm to inquire into the wrongdoings of his officers amongst others. The ayre appears to have been carried out.[37] That seems to have established the pattern for the remainder of his reign for Wyntoun’s comment that the king “ilka yere a justry/ … gert hald rycht fellonely” (i.e. fiercely)[38] seems to be borne out by surviving record. Indeed, the very first piece of evidence for this period allows us to see justice ayres operating twice in the year. Thus, William Meldrum held an ayre at Cupar for eight days from 31 January 1358 and subsequently received expenses.[39] Later in the year there was an ayre in the north that began at Inverness on 1 October, had reached Inverbervie by the 15th, and on 5 November was at Cupar.[40] It is likely that the ayre passed through Perth on this journey or on the one earlier in the year, for William Meldrum received his expenses as justiciar’s lieutenant for 1358 in that burgh also.[41] There had been ayres in Peebles, Lanark, and Forfar by the spring of 1359,[42] and in the same year there was another at Perth.[43] Records show ayres at Stirling in the south and Forfar in the north in 1360.[44] William, earl of Douglas, held a justice ayre in Edinburgh before 1361.[45] It seems, therefore, that if there had been inactivity in the king’s absence his return certainly prompted a change in the picture. It is probably not coincidental that in April 1360 King David ordered the renewal of payments to the bishop of Aberdeen from the issues of the justiciary courts in Aberdeen and Banff.[46]

Such specific evidence cannot be found in subsequent years within David’s reign, but year by year in the 1360s the exchequer rolls contain references to the issues of justice ayres, the expenses of the ayres, and the fees paid to the justiciar: for example, in 1361, 1362, 1364, 1365, 1368, and 1369.[47] Some of these issues could be and frequently were granted away as annual pensions to such men as John Gray, clerk of the rolls, and John Lyon, the king’s secretary,[48] while in 1365 the king commanded that the fee of the sergeant of the sheriffdom of Lanark should be paid inter alia from the issues of the justice ayres within the sheriffdom in accordance with old custom and the verdict of an assize before the sheriff of Lanark.[49] The implication is that the ayres were a continuing source of both income and expenditure in this period, and it would seem to follow that they were being held on at least an annual basis.

Some of the gaps left by the financial records can be filled by other evidence. So, in July 1366 a court of the justice ayre of Lothian was held at Melrose,[50] while the dooms of justice courts at Forfar, Dundee, Peebles, Dumbarton, Edinburgh, and Dumfries were falsed in parliament in 1368 and 1370.[51] In 1371, the earl of Ross complained to Robert II that David II had so acted as to prevent him paying suit at the court of the justiciar when it was held at Inverness.[52] All this taken together suggests that justice ayres, north and south, were a regular feature of the latter part of David’s reign.

Despite contemporary criticism of the failure of the first two Stewart kings, Robert II and Robert III, to administer the law,[53] there is also a good deal of evidence that justice ayres were held with regularity in their reigns, particularly in the north. In the 1370s, James and Alexander Lindsay of Glenesk regularly received fees for acting as justiciars north of Forth,[54] while in the 1390s the same may be said of Murdoch Stewart.[55] In 1406, the duke of Albany was allocated one hundred pounds for holding five justice ayres north of Forth.[56] The exchequer rolls continue to speak of the issues and expenses of the ayres.[57] A grant from the issues south of Forth could be made to Alan Lauder the justice clerk in 1373, while in 1382 Alexander Strachan of Carmyllie, a royal scutifer, was to be paid his fee for his office of coroner in Angus and the Mearns proportionately from the issues of the justiciary of the sheriffdoms of Forfar and Kincardine.[58] In 1379, the right of the king’s judex Andrew Dempster to an amercement from each justice ayre of Forfar was confirmed.[59] In 1397, there is another reference to the profits of the Forfar justiciary.[60]

It seems, therefore, that the ayres remained a significant source of royal income. A reference in the account of the sheriff of Lanark for 1388 mentions that two justice ayres were held within his bailiary in 1381,[61] although it should be noted that in the former year the sheriff of Fife could not account for any issues from the justice court because none had been held.[62] The financial evidence may be supplemented from the records of various cases before the justiciars in the period, including ones of mortancestor, of slaughter and other crimes, and of falsing the dooms of sheriff courts.[63] In short, there seems no doubt that justice ayres were a regular feature of life in the latter part of the fourteenth century.

Justice Ayres 1406–1488

The Albany governorship (1406–24) leaves little trace in its records of the holding of justice ayres other than references to ayres south of Forth in 1410 and 1411, and at Stirling in 1414.[64] In 1409 Duke Robert stipulated for suit at the court of justiciary held in Stirling,[65] while in 1420 Duke Murdoch made an agreement with Alexander Stewart, earl of Mar, concerning the profits of the “justry” of Aberdeen, Banff, and Inverness.[66] The latter document suggests that it would be rash to draw too many conclusions from the lack of evidence for this period.

If the ayres lapsed under the Albanys, then there was a revival after the return of James I in 1424. There are references to justice ayres north and south of Forth in 1425, 1433, 1434, and 1435.[67] In 1431, the king commanded the justiciar south of Forth to pay second teinds of the issues of the justiciary to the abbot and convent of Scone, showing again the significance of the ayres as a source of profit.[68] Two years later, in July 1433, Walter Stewart, earl of Atholl and justiciar north of Forth, held an ayre of his regality of Atholl at Logierait, before moving on to hold a royal ayre at Perth.[69] A glimpse of the preparations for the autumn ayre of 1435 is afforded by the letter sent from Perth by Earl Walter as justiciar north of Forth to the sheriff of Kinross commanding him to summon suitors to the justice court.[70]

What happened in the period between the death of James I in 1437 and the assumption of full power by his son in 1449 is extremely obscure. We know of an ayre at Jedburgh in 1437.[71] The exchequer rolls at this time refer mainly to the holding of ayres within regalities that had fallen into crown hands, such as Annandale and the earldoms of Strathearn and March.[72] But in 1448 there was a dispute as to whether the bishop of Brechin owed suit of court when the justice ayre came to Inverbervie, caput of the sheriffdom of Kincardine. The case was determined by an assize in the sheriff court of Kincardine and it was held that the bishop had not been seen to give suit at the justice court, nor had he ever been amerced or punished for being absent.[73] This suggests that justice courts had been held with some regularity in the sheriffdom. More concrete evidence for the holding of ayres on a regular basis can be found in the 1450s.[74] Thus, Goddo Dow and McKannane were hanged at the justice ayre of Stirling in the spring of 1453 after conviction for their trespasses.[75] Two ayres were held at Cupar in 1454: one in January, the other in June.[76] In both, the court heard cases of falsing the doom from the sheriff court of Fife. Ayres seem also to have been held with a fair degree of regularity at centres such as Dumfries, Kirkcudbright, Wigtown, and Ayr in the southwest,[77] and were also recorded at Edinburgh, Peebles, and Jedburgh.[78] In the mid-1450s (we cannot be more precise as to date), James II attended an ayre in the north that progressed from Inverness through Elgin to Banff.[79] In 1455 and 1457 there were ayres at Aberdeen.[80]

The 1450s seem then to have been a period in which justice ayres were held regularly. So also the 1460s, the period of the minority of James III. There are references to ayres being held before the queen mother, Mary of Guelders, at Edinburgh,[81] and on her behalf by Andrew, lord Avondale, the chancellor, at Dumfries, between 1460 and 1464.[82] Avondale held an ayre as justiciar south of Forth at Ayr in March 1460.[83] Another ayre is recorded at Ayr in January 1466.[84] The “justice ayris of Wigtoune,” where three men were “justifiit” and escheated, are referred to as recent events in October 1466.[85] There was an ayre at Selkirk in 1466.[86] In November 1469, the dooms of ayres held at Dumfries in July 1467 and October 1468 were falsed in parliament.[87] Thus it appears likely that there was still a fair degree of regularity in the holding of the ayres despite the various political crises of the period.

James III assumed active authority in late 1469 and, as with his father, this event seems to lead to much more frequent reference to justice ayres in the financial records. There was an ayre at Selkirk on 19 February 1470[88] and, assuming that the usual southern circuit was being followed, it had reached Ayr by 23 March.[89] Inferences about this southern circuit may be made from other references in the exchequer rolls to the holding of ayres in Edinburgh,[90] Lauderdale,[91] and the sheriffdom of Roxburgh before June 1470.[92] It seems possible that this ayre was also at Stirling.[93] It was probably followed by a northern ayre in the summer of 1470. We know that it was at Perth in June and at Cupar on the 18th of that month.[94] Another ayre was held at Perth in November;[95] this is one of the rare instances where there is clear evidence of ayres being held in a region twice within one calendar year, in accordance with old use and custom.

There is less detail for subsequent years, but still plenty of material giving glimpses of regular ayres throughout the 1470s. In 1471, for example, Robert, lord Lyle, justiciar north of Forth, held an ayre at Cupar that gave a doom upon a brieve of mortancestor later falsed before the parliamentary auditors. The appeal related only to a preliminary point and the case was still continuing in 1478, when another doom given upon it before John Haldane of Gleneagles as northern justiciar was also dealt with in parliament.[96] Another example of the doom of a justice ayre being falsed in parliament may be found in October 1476; the doom had been given “in the justice ayre of Edinburgh the 12 day of Julii last bipast.”[97] In November 1472, Master David Guthrie, justiciar south of Forth, held an ayre at Ayr.[98] The details of an ayre in the southwest in the late autumn of 1473 emerge clearly from the earliest surviving treasurer’s accounts, in which are listed the compositions given by those convicted at ayres in Dumfries, Kirkcudbright, Wigtown, and Ayr.[99] Quite apart from anything else, this tantalising record shows how much it was in the interests of the royal finances to hold justice ayres. The same source records the payment of £100 to Guthrie as his fee in the office of “justry.”[100] A year later, a sum of money was “gevin to ane passand to the lorde of Erskin for the continuacioune of the Justice Are of Strivelin.”[101] From a little later in the 1470s there are references to ayres at Haddington (presumably as a constabulary of the sheriffdom of Edinburgh) and Peebles and to “my lord of Albanys justice aire.”[102] The impression of the stability and routine nature of the system is confirmed by the confident statements made by the king’s council at the end of the 1470s about the next justice ayres in Cupar, Perth, and Jedburgh;[103] there were no doubts that these ayres would be held in the near future.

The following decade is one in which parliament frequently called upon the king to hold his justice ayres, but, as already argued, it is in this period that the source from which we have derived most evidence for the holding of ayres, the exchequer rolls, suddenly ceases to assist. The ninth volume of the printed series covers the years 1480 to 1487 and contains only two references to justice ayres. The first suggests that one needs to be held, to inquire into certain deforcements in Galloway;[104] the other is to the ayre that was in fact held, subsequently, at Kirkcudbright in 1487.[105] Other sources are barely more helpful. An ayre was held in the town of Ayr in 1487, perhaps following the one at Kirkcudbright; we learn of this from a chance reference in the Acta Dominorum Concilii for 1492.[106] An entry in the same record a few years later tells of a justice ayre of Fife, also in 1487.[107] However, there may have been a breakdown of the system earlier in the decade, perhaps as a result of the major political crisis of 1482–83.[108] In March 1482, the auditors of causes and complaints ordered that an inquest be held on certain matters at the next justice ayre of Peebles. The inquest was held, but not until February 1485.[109] This may mean that there had been no southern ayre in the intervening period or, alternatively, that the amount of other business to be done in Peebles had not justified any ayre there until then. Certainly there was a justiciar south of Forth during at least part of those three years, for Archibald, earl of Angus, had been forced to resign the office in March 1483.[110] As argued elsewhere, this should not be taken as an indication of a failure by Angus to discharge his duties properly. He had been one of the leaders of the opposition party who precipitated the crisis with James III at Lauder in July 1482 and there is every reason to suppose that he acquired the office in consequence of this, as for a long time prior to the crisis he had been out of favour with the king. It is, indeed, possible that he went on ayre in the autumn of 1482.[111] The dismissal of Angus came when James regained full authority.

The evidence thus shows that, whatever may or may not have been happening earlier in the decade, ayres were held in 1487. In January 1488, ayres had been “set” but were “dissolvit and disertit” by order of parliament, with provision that new ones were to be “proclamyt and gert of new to be haldin on the gerss”—that is, in the spring.[112] There exists one reference to a justice ayre of Selkirk in 1488 in the time of James III.[113] Presumably this was the result of a proclamation following the January parliament, since the king was overthrown and killed in early June. It is far from easy, therefore, to assess the scanty evidence for the 1480s. What can be said is that firm conclusions that the ayres were not held have no foundation beyond the fragmentary nature of the evidence showing that they were held at least occasionally.

Justice Ayres in the Reign of James IV

The reign of James IV brings about a transformation in the nature and amount of record information concerning the justice ayres, which has led some commentators to infer a resurgence in the ayres themselves by comparison with what had gone before. Again, caution ought to be observed before this conclusion is adopted wholesale. The record from which we can glean most information for the early years of this reign is the accounts of the treasurer, which broadly are extant only from the beginning of the reign. Moreover, the records of the southern justice courts themselves are available in part from 1493 on.[114] Especially with regard to the former, the accident of survival has surely little to do with any substantive change in the country’s judicial arrangements. For example, the extent of references to justice ayres in the treasurer’s accounts is entirely dependent on whether or not the king was in attendance. Nothing is said in them of the ayre at Edinburgh in July 1491 and in January 1493, of which we learn from the exchequer rolls.[115] The treasurer’s accounts do tell us of a southern ayre held from February to April in 1490,[116] but not of the northern ayre that was taking place at the same time.[117] The point is again that silence without more should not be accorded any particular evidential value one way or another.

The evidence for the reign up to 1500 is undeniably much more impressive than previously, with the ayres apparently at least annual events. The new king was on ayre at Dundee in September 1488;[118] in November he was south of Forth at Lauder.[119] This latter ayre also appears to have taken in Lanark.[120] From January to March 1489 the king was in ayre in the south, passing through Jedburgh, Selkirk, Peebles, Dumfries, Wigtown, and Ayr.[121] This ayre was also at Kirkcudbright on 1 March.[122] In the spring of the following year an ayre was at Jedburgh, Lanark, and Edinburgh,[123] while in the north there was an ayre at Cupar.[124] In November 1490, Ormond, a messenger, was sent north to “proclaim the ayris.”[125] Sometime in that year there was a case of showing the holding in a justice ayre at Stirling.[126] There was an ayre at Edinburgh in July 1491,[127] while in October a messenger was sent to proclaim the ayre at Lanark.[128] In January 1492, another messenger was sent to Lanark to provide for a forthcoming ayre there; yet another was sent to the town of Ayr with a continuation of the ayre actually being held there.[129] In February, John lord Drummond received his “costis” in the ayres of Lanark, Selkirk, Edinburgh, Perth, Dundee, Bervie, and Aberdeen, that is, both north and south of Forth.[130] In May, commissions and other letters for the next northern ayre were being sent out,[131] and in August a number of individuals were reimbursed for their costs in ayres at centres such as Lanark, Ayr, Stirling, and Perth.[132] In January 1493, a justice ayre was held at Edinburgh,[133] while at some uncertain date in that year there was also one at Aberdeen.[134] It is in 1493 that fragmentary justiciary records become available, telling us of an ayre that was at Lauder from 7 to 14 and at Jedburgh from 16 to 21 November of that year.[135] In the summer of 1494, the king sent out letters to continue the ayres of the “Northland.”[136] A royal justice court was held at Edinburgh before the depute of the justiciars south of Forth on 4 August 1494.[137] Another northern ayre was proclaimed and commenced at Inverness on 6 October.[138] It reached Elgin on 30 October and, passing through Banff, was at Aberdeen on 10 November.[139] From there, a messenger was sent to the king carrying the “extracts” of the ayre.[140] A southern ayre in spring 1495 can also be partially reconstructed from the treasurer’s accounts and from those of its records that have survived. It started in Edinburgh on 2 February. It reached Jedburgh on 25 February and worked there until 3 March. On the following day the ayre was at Selkirk where it remained until 7 March. The next stop was Peebles on 9 March, then Lanark on the 16th, Dumfries on the 23rd, and Kirkcudbright on 6 April. The circuit ended at Ayr.[141] Letters had to be sent for the continuation of this “Southland” ayre.[142] There was also a justice ayre at Ayr in July 1495, presumably the second there that year.[143] Finally, we know that an ayre was in the north at Inverness in 1495.[144]

There are numerous references to these and later ayres in the printed records of the lords of council and of the parliamentary auditors of causes and complaints up to 1503.[145] But the evidence for the later years of the 1490s is not quite so detailed and interesting as it is for the period 1488–1495. However, the records do allow us to see the complete northern circuit in an ayre held in January and February 1498. It began at Inverness and passed through Elgin, Banff, Aberdeen, Bervie, Dundee, Perth, and Cupar.[146] In the same year there was an ayre at Edinburgh in June[147] and at Jedburgh in October.[148] In November, this ayre was at Peebles for six working days.[149] There was an ayre at Wigtown in February 1499 that by March had reached Ayr.[150] Two southern ayres seem to have been held in 1500: certainly one was at Jedburgh in March and another at Lanark in October.[151]

The Justice Ayre: Routeways and Roads

This evidence from the late fifteenth century has been laid out in some detail because it enables us to pull together the earlier fragments, which are all that we have to show the operation of the ayres before then. Perhaps James IV did drive the ayres as they had never been driven before, but he certainly drove them along old-established tracks. In the 1260s the ayre of the justiciar of Scotia began at Inverness and passed through the sheriffdoms of Invernairn, Forres, Elgin, Banff, and Aberdeen, before turning south to Kincardine, Forfar, Perth, and Fife.[152] This is all but identical to the circuit of 1498 described in the previous paragraph. The only differences are the disappearance of Nairn and Forres, subsumed in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries within the sheriffdoms of Inverness and Elgin respectively, while Kincardine was replaced by Inverbervie, probably sometime in the reign of David II.[153] It should also be noted that while within the sheriffdom of Forfar ayres were held at both Forfar and Dundee in the fourteenth century, the latter seems thereafter to have supplanted the former.[154] In Fife, we know of one ayre held at Kinghorn in 1435,[155] but Cupar seems to have been the usual location.

South of Forth the pattern was less settled. The justiciarship of Galloway (established in the thirteenth century[156]) was absorbed into that of Lothian, to become together the justiciarship south of Forth. In the 1260s, the ayre of the justiciar of Lothian included the sheriffdoms of Berwick and Roxburgh;[157] the courts were no doubt held in the burghs of these names. Change became necessary when, in the fourteenth century, both burghs passed into English hands. A document of 1372 under the name of William, first earl of Douglas, then justiciar south of Forth, explains that, although it had been the custom to hold a justice ayre at Berwick, that was not possible while the town remained subject to the English and so ayres had to be held at other places within the sheriffdom. The document goes on to state that while it had been convenient to hold the ayre at Coldingham, this was not to set a precedent for the future.[158] Perhaps similar reasons lie behind the holding of an ayre at Melrose in Roxburghshire by the justiciar of Lothian in 1366:[159] it is worthy of note in this connection that in 1360 Melrose abbey carefully obtained a full statement of its regalian rights from the king, stating that justiciars and other royal officers were to be firmly interdicted from any disturbance of those rights.[160] Did this represent a precaution made necessary by the establishment of Melrose as the ayre town of the sheriffdom of Roxburgh? In the long run, Lauder and Jedburgh (itself recovered from English occupation only in 1409) became the ayre towns of Berwick and Roxburgh respectively. It seems clear that the principle stated at the end of the thirteenth century in the so-called ‘Scottish King’s Household’, that the justiciar should hold his courts at the caput of each sheriffdom within his jurisdiction, held good throughout the later middle ages.[161]

A typical southern ayre of this period would thus have commenced at Edinburgh before proceeding first to Lauder for the ayre of the sheriffdom of Berwick and then to Jedburgh for the ayre of Roxburgh. The journey would be facilitated by the main road on the line of the Roman Dere Street, still a principal route in the medieval period.[162] The ayre would then move over Teviotdale, perhaps back up Dere Street as far as Melrose, before going down the Ettrick Water to Selkirk for its ayre. Yet another road, possibly Roman in origin, led from Selkirk on to Peebles and probably from there to Lanark, the next two stopping places of the ayre.[163] From Lanark, the ayre first crossed the River Clyde, perhaps by ford or ferry at the “extremely placid reach of the river, extending from Hyndford Bridge to Bonnington Fall,”[164] and then turned south to Crawford, once more utilizing a road (on the line of the modern A73) perhaps originally constructed by the Romans.[165] From Crawford, the road crossed into Nithsdale through the Lowther Hills by way of the Daer and Potrail waters and Durisdeer, before heading down the River Nith to Dumfries.[166] From Dumfries, where the Nith was bridged, ayres would follow at Kirkcudbright and Wigtown. While the use of originally Roman routes here is possible,[167] sea travel may have provided an easier alternative. The final turn north for Ayr may have traversed the Galloway and Carrick hills by following the course of the River Cree and the line of the modern A714 to Girvan and thence, this time on the line of the modern A77, to Ayr. Again, sea transport could have made this particular stage of the journey rather easier and quicker, although possibly by going first overland from Wigtown to take ship in Loch Ryan, thus avoiding the dangerous rip tides around the Mull of Galloway. The next stop after Ayr was normally at Dumbarton. Once more, ship travel between the towns is a possibility; an overland journey would mean a ferry crossing of the Clyde at Erskine (or Renfrew if the ayre happened to pass that way, as it sometimes did in the later fifteenth century).[168] From there it would be a northeasterly journey to Stirling to conclude the ayre

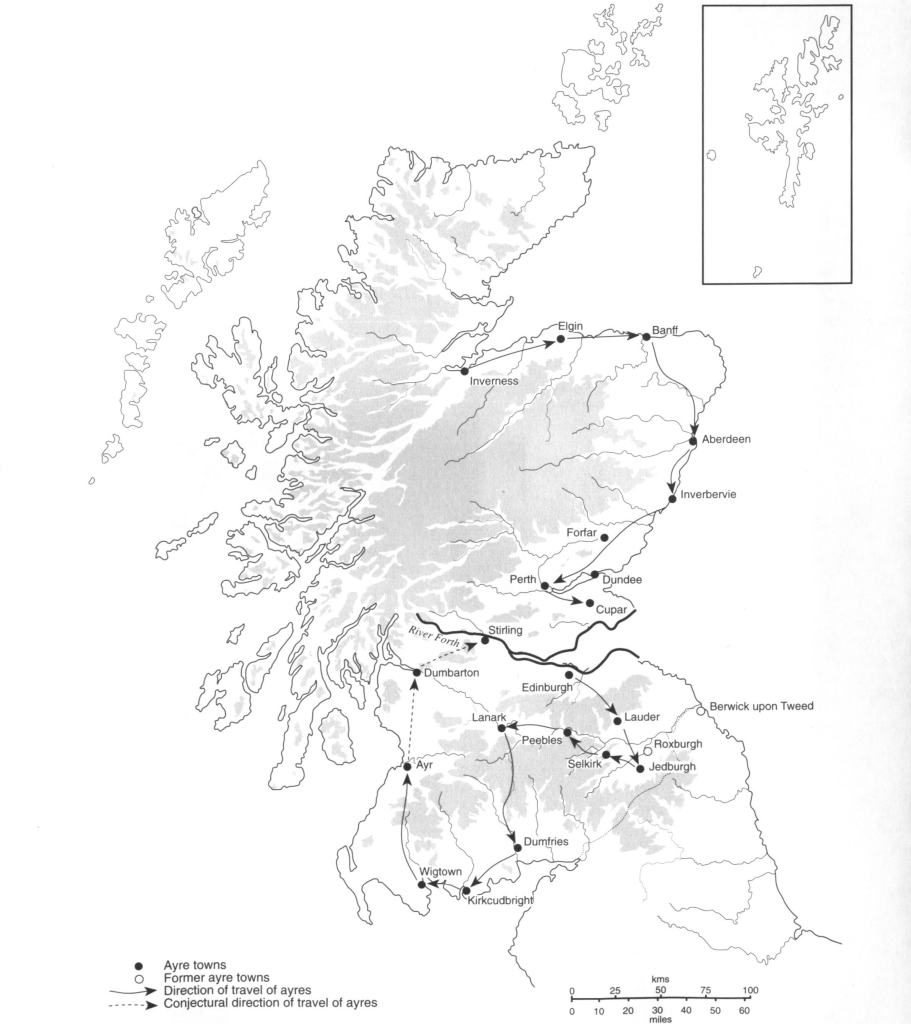

Figure 3.1: Map of Justice Ayres in the Fifteenth Century

Image from Atlas of Scottish History to 1707, eds. Peter G.B. McNeill and Hector L. MacQueen (Edinburgh: Conference of Scottish Medievalists, 1996), 211. Reproduced with permission of the Trustees of the Conference of Scottish Medievalists.

The logic of this circuit can be plainly seen upon the map and similar logic is even more apparent in the north.[169] The starting point was Inverness from where the ayre would proceed in an easterly direction to Elgin (following a well-established royal road[170]), and then to Banff before moving southeast to Aberdeen, crossing the Don by way of the Brig of Balgownie. The route south from Aberdeen may have begun with a ferry across the Dee to Torry,[171] before taking the coast road to Inverbervie, probably fording the Bervie Water just below the burgh.[172] From there, the ayre probably headed further down the coast to ford the North Esk near its mouth, and then took the ferry over the South Esk between Montrose and Ferryden.[173] The ayre could then proceed to either Forfar (taking the line suggested by the modern A934 and B9113[174]) or Dundee (taking the line by Arbroath abbey suggested by the modern minor road running from Ferryden to Arbroath).[175] From Forfar there was a pretty straight westward route via Coupar Angus abbey to Perth, on the line of the modern A94; from Dundee the ayre would have to traverse the Carse of Gowrie by the road running through Longforgan, Errol, Inchyra, and St Madoes. In either case, the last stage of the journey reached the high street of Perth by way of a bridge over the Tay.[176] From Perth, the ayre would re-cross the Tay to start for Fife, with the crossing, this time by ferry, at the Tay’s confluence with the Earn.[177] From here, there may have been a choice of routes, going via either the Cross MacDuff or Newburgh to reach the lands of Lindores abbey, before taking something like the line of the modern A913 to reach the ayre’s final stopping point, at Cupar.[178]

The distances between each ayre town vary and the evidence does not allow us to analyse the ayre’s typical speed of progress. A reasonable guess would be that it travelled around 20 miles each day.[179] Ferry crossings of large numbers of people, animals and carts might well have been a factor slowing progress. Where more than one day’s journey had to be made between towns, accommodation was most likely found en route: for example, at Coupar Angus abbey between Inverbervie and Forfar (or Arbroath abbey if the ayre went to Dundee rather than Forfar), or at Melrose abbey between Jedburgh and Selkirk. The duty of hospitality may account for some of the parliamentary grumbles in 1450 about the burdens ayres imposed on local communities.[180]

Study of the ayre routes on the map shows one other point. It is clear that an ayre of the later medieval period visited each of the main sheriffdoms as established by the end of the reign of Alexander II in 1249. There is, however, no record of any ayres in the sheriffdoms of Cromarty, Argyll, or Tarbert, all of which first appear or were erected in the second half of the thirteenth century but which do not seem to have survived into later centuries.[181] A most striking feature of the northern ayre in particular is therefore its eastward orientation; the regions north and west of Inverness appear never to have been visited by royal justice ayres. But other arrangements frequently prevailed in these areas. There were special justiciars for those parts, such as Arran, Cowal, and Bute, which were crown lands,[182] while in 1430 James I made a seven-year grant to the keepers of Kintyre and Knapdale in Argyll with “full power of holding our courts of the sheriff and the justiciar, punishing and fining trespassers in the form of the common law of our realm.”[183] In the far north, the Sinclair earls of Caithness held the office of justiciar heritably in their earldom (which was also a regality),[184] while from 1489 there was a similar office in Orkney and Shetland together, although the record leaves obscure who the office-holders were to be at that point.[185]

Grants of regality jurisdiction (which could include that of justiciars, and accordingly had their own justiciars) may also have helped to fill some if not all of the apparent gaps, for instance in Atholl and Strathearn, as well as Moray (which for these purposes included Badenoch, Lochaber, Mamore, and Glenelg) and Caithness.[186] The example of Walter Stewart, earl of Atholl, acting more or less simultaneously not only as the king’s justiciar but also as justiciar in his own earldom illustrates the interaction possible between the jurisdictions.[187] Perhaps more significant, however, were the royal lieutenancies in Argyll and northern Scotland from the reign of Robert II (1371–90) on, in which magnates such as the Campbell earls of Argyll and the earls of Huntly and Ross, who already had their own significant power and authority in these regions as well as loyalty to the king, were charged with government in the king’s name.[188] The Western Isles may have been left to the Lords of the Isles and their own legal system, however, until the forfeiture of the Lordship to the crown in 1493.[189]

In 1504, parliament bemoaned the lack of justice ayres, justices, and sheriffs in the north and west parts of the realm whereby “the pepill ar almaist gane wild.” Justiciars and sheriffs were to be appointed in the northern and southern isles, sitting in the former case at Inverness or Dingwall, in the latter at Tarbert (Knapdale) or at Lochkilkerran (site of a new royal castle erected in 1498, now Campbeltown, Kintyre). Parliament went on to deal with other areas that had been “out of use to cum to our justice airis”—the lands between Badenoch and Lorne called Dochart and Glendochart, the lordship of Lorne itself, Mamore, Lochaber, and Argyll. Dochart and Glendochart and the lordship of Lorne should pertain to the ayre of Perth, as should Argyll “when it pleased the king.” The more northerly Mamore and Lochaber should go to the ayre of Inverness, however. The justice of the lordship of Argyll should sit at Perth, while the ayres of the crown lands of Bute, Arran, Knapdale, Kintyre, and Cumbrae should be held at Ayr or Rothesay. That part of Cowal not in the lordship of Argyll should belong to the ayre of Dumbarton.[190] All this seems to have been intended to make for easier access to royal justice against the inhabitants of the west and north, whether in civil or criminal matters.[191]

We need not accept the parliamentary view that the lack of justice ayres in the areas mentioned had led to lawless anarchy[192] in order to recognize that each of them was by virtue of its geographical position and internal topography likely to have been difficult to administer effectively from such relatively remote centres of government as Perth and Inverness. It would probably have been virtually impossible for a full-blown justice ayre to make its way into the regions in question, given the difficulty of east-west routes through the mountainous terrain. It would not have been much easier to reach for the would-be pursuer or accuser of a defender living there, even if local courts were available for the purpose.[193] Clearly, the acts of 1504 represent an attempt to exert a greater degree of central control of the administration of justice in areas where previously much had depended upon the men on the spot, such as the Lord of the Isles and the earl of Argyll, and their officials.[194] It is beyond the scope of this study to determine how successful their efforts had been, or how and whether the reforms of 1504 worked in practice.[195] But it is worth noting that the same parliament also declared that “all oure soverane lord liegis beande under his obeysance, and in speciale the Ilis, be reulit be oure soverane lordis aune lawis and the commoune lawis of the realme ande be nain uther lawis.”[196] Insofar as local customary rules and modes of doing justice had perhaps hitherto prevailed, especially in the Northern and Western Isles, they were no longer to be tolerated.[197]

The final observation to be made is that the lack of justiciary records and the legislative statements calling for ayres to be held cannot be used to support an argument that the ayres were in fact held irregularly or infrequently. An examination of the evidence surveyed in this chapter suggests that in at least some years two ayres were indeed held north and south of Forth, in accordance with “old use and custom,” and that, overall, the justiciars followed consistent circuits in each region with considerable regularity throughout the later medieval period. The visit of an ayre to a particular town on the circuit may well have depended on whether there was sufficient business to be transacted there, but the evidence we have suggests that when they took place such visits could last for several days, while the circuit as a whole might take two or three months to complete. Viewed in the round, the evidence implies not only ongoing administration of royal justice throughout most of the later medieval period, but also, in the east and south of the kingdom, established networks of major roads and routeways making use of ferries, fords and bridges, without which the system would have been inoperable and, indeed, inoperative.

- I am very grateful for the help, support, and insights provided by Frances MacQueen as we have explored the routes of the justice ayres together over many years, and also for the helpful suggestions made by the anonymous referees ↵

- See so far G. W. S. Barrow, “Land Routes: The Medieval Evidence,” in Loads and Roads in Scotland and Beyond: Road Transport over 6000 Years, eds. Alexander Fenton and Geoffrey Stell (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1984), 49–66 (reprinted in G. W. S. Barrow, Scotland and its Neighbours in the Middle Ages (London and Rio Grande, Ohio, USA: Hambledon Press, 1992), ch. 10); R. P. Hardie, The Roads of Medieval Lauderdale (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1942); Richard D. Oram, “Trackless, Impenetrable and Underdeveloped? Roads, Colonization and Environmental Transformation in the Anglo-Scottish Border Zone, c.1100 to c.1300,” in Roadworks: Medieval Britain, Medieval Roads, eds. Valerie Allen and Ruth Evans (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), 303–21; and Bruce F. Manson, “In Search of Pilgrim Routes across Southern Fife, 1100–1550,” Innes Review 72 (2021): 128–57. Also very useful is the Old Roads of Scotland website created by Gerald Cummins (http://oldroadsofscotland.com/index.html). ↵

- Grant G. Simpson, “The Medieval Topography of Old Aberdeen,” in Old Aberdeen: Bishops, Burghers and Buildings, ed. John S. Smith (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1991), 1–13, 2. ↵

- See Peter Yeoman, Pilgrimage in Medieval Scotland (London: B. T. Batsford/Historic Scotland, 1999), 37–9 (Whithorn), 55–62 (St Andrews), 72 (Dunfermline), 101–6 (Tain and Whithorn); Manson, “Pilgrim Routes,” passim. ↵

- Elizabeth Ewan, Townlife in Fourteenth-Century Scotland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990), 67–8. ↵

- Barrow, “Land Routes,” 51. A comparison with medieval England is instructive: see Graeme J. White, The Medieval English Landscape, 1000–1540 (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), 108–16. ↵

- See for all this Hector L. MacQueen, Common Law and Feudal Society in Medieval Scotland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993, repr. 2016), 63–4. ↵

- K. M. Brown et al., eds., The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, www.rps.ac.uk [hereafter RPS], 1450/1/19. ↵

- Miscellany of the Scottish History Society vol. 2 (1st Series, Edinburgh, 1904), 36–7 (in “The Scottish King’s Household,” ed. M. Bateson); RPS 1440/8/3, 1450/1/12, 1485/5/10, 1491/4/14. ↵

- W. C. Dickinson, “The High Court of Justiciary,” in Introduction to Scottish Legal History, ed. G. C. H. Paton (Edinburgh: Stair Society vol. 20, 1958) 408–12, 408. ↵

- MacQueen, Common Law, 60 ↵

- Ibid., 61. ↵

- For the lack of sheriffs’ accounts see Bruce Webster, Scotland from the Eleventh Century to 1603 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), 139. For the evidence found in the exchequer rolls see also ibid., 133–41. Note especially the point that the exchequer rolls are not records of actual income and expenditure but are rather charge/discharge accounts. For a helpful account of exchequer procedure see A. L. Murray, “The Procedure of the Scottish Exchequer in the Early Sixteenth Century,” Scottish Historical Review [SHR] 40 (1961) 89–117, especially at 104–6, for the evidence of the sheriffs’ accounts on justice ayres. ↵

- Webster, Scotland, 143, 211. ↵

- G. W. S. Barrow, The Kingdom of the Scots 2nd edn (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), 95. ↵

- See further below, text between nn 166 and 167. ↵

- See Hector MacQueen, “Tame Magnates? The Justiciars of Later Medieval Scotland,” in Kings, Lords, and Men in Scotland and Britain, 1300–1625, eds. Steve Boardman and Julian Goodare (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 93–120, 95. ↵

- Miscellany of the Abbotsford Club, Volume I (Edinburgh: Abbotsford Club, 1837), 53–6. See further G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, 4th edn (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), 370 (describing Keith as “one of the [Scottish] king’s indispensable commanders and administrators” from Christmas 1309; for this date rather than Barrow’s 1308 see Michael Penman, Robert the Bruce King of the Scots (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), 108). Keith had previously been justiciar for the region from the Forth to the Mounth in the English administration (MacQueen, “Tame Magnates?” 95 n. 12). ↵

- Regesta Regum Scottorum, Volume V: Acts of Robert I, ed. A. A. M. Duncan (Edinburgh, 1988), no 139 (ch. xi); RPS 1318/13. ↵

- Liber ecclesie de Scon (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1843) [hereafter Scone Liber], no. 130. ↵

- RRS v no. 168; Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum, eds. J. M. Thomson et al (Edinburgh, 1882–1914) [hereafter RMS], i no. 70; Registrum Sancte Marie de Neubotle, ed. C. Innes (Bannatyne Club, Edinburgh, 1849) [hereafter Newbattle Registrum], no. 58 ↵

- RRS v no. 66. ↵

- RMS i no. 163 (confirmation by David II of pension granted to Lauder by Robert I); RRS v nos 140, 269; RMS i app. I no. 12; Liber Sancte Marie de Melros, ed. C. Innes (2 vols, Bannatyne Club, Edinburgh, 1837) [hereafter Melrose Liber], ii no. 361. ↵

- RRS v no 267; RMS i app. 1 no 38; W. Fraser, The Douglas Book (four vols., Edinburgh, 1885), iii no. 14. ↵

- The Exchequer Rolls of Scotland, ed. J. Stuart et al (Edinburgh, 1878–1908) [hereafter ER], i 396. ↵

- Regesta Regum Scottorum, Volume VI: Acts of David II, ed. B. Webster (Edinburgh, 1982), no. 101; Newbattle Registrum no. 272; above, text accompanying n. 20. ↵

- See below, text accompanying nn. 156–9. ↵

- ER i 444. ↵

- The British Library, MS. Add. 33245, ff. 156 v–157r. ↵

- ER i 521. ↵

- RRS vi no. 70. ↵

- Liber Sancte Thome de Aberbrothoc, eds. C. Innes and P. Chalmers (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1848–1856) [hereafter Arbroath Liber], ii no. 22. ↵

- W. Fraser, History of the Carnegies, Earls of Southesk, and of their Kindred (Edinburgh, 1867), ii no. 36. Forfar was a burgh and a sheriffdom by the mid-12th century, while Dundee became a royal burgh before the end of the thirteenth century (G. S. Pryde, The Burghs of Scotland: A Critical List, ed. A. A. M. Duncan (London, Glasgow and New York: Oxford University Press for University of Glasgow, 1965), nos 23, 29, 94. ↵

- Registrum Episcopatus Aberdonensis, ed. C. Innes (two vols, Spalding & Maitland Clubs, 1845) [hereafter Aberdeen Registrum], i 79–81. ↵

- A. B. Webster, “David II and the Government of Fourteenth Century Scotland,” TRHS 5th series, 16 (1966) 115–30, 121. See also Michael Penman, David II, 1329–71 (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2004), 142–3. ↵

- ER i 546. ↵

- RPS 1357/11/7; Webster, “David II,” 131 n. 7 and 117 n. 5; Penman, David II, 198–9. ↵

- Andrew of Wyntoun, The Orygnale Cronykil of Scotland, ed. David Laing (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1872), ii 506–7, cited in Webster, “David II,” 117. ↵

- ER i 561, 562. ↵

- ER i 561, 570, 586–7; Penman, David II, 209–10. ↵

- ER i 558–9. ↵

- ER i 569, 583, 590. ↵

- ER ii 82. ↵

- W. Fraser, The Red Book of Menteith (Edinburgh, 1880), ii no. 29 (Stirling); RMS i app 1 no. 145 (Forfar). ↵

- ER ii 82. ↵

- RRS vi no. 234. ↵

- Issues: ER ii 171, 176, 306; Expenses: ER ii 82, 117; Fees: ER ii 82, 176. ↵

- RMS i no. 161 (Gray); RRS vi no. 431 (Lyon). ↵

- RMS i no. 199. ↵

- James Raine, The History and Antiquities of North Durham (J.B. Nichols, 1852), no. 326. ↵

- RPS 1368/6/1–5, 1370/2/17–22. ↵

- Ane Account of the Familie of Innes (Spalding Club, 1864), 70–2. ↵

- See Alan R. Borthwick and Hector L. MacQueen, Law, Lordship and Tenure: The Fall of the Black Douglases (St Andrews: Strathmartine Press, 2022), 40–7. ↵

- See ER ii 435, 437, 458, 620; ER iii 30, 652. ↵

- ER iii 316, 347, 376. ↵

- ER iii 644. ↵

- ER ii 394, 430, 435, 437, 438, 457, 458, 462, 620; ER iii 174, 166, 167, 241, 265, 268, 315, 643; ER iv 133, 212, 595, 634. ↵

- RMS i nos 456 (Lauder) and 735 (Strachan). ↵

- RMS i no. 758. ↵

- Fraser, Douglas iii nos 45 and 48. ↵

- ER iii 164. ↵

- ER iii 166. ↵

- e.g. Fraser, Menteith ii no. 43; Report of the Royal Commission On Historical Manuscripts [hereafter HMC], iii 417; Registrum honoris de Morton, ed. T. Thomson, A. Macdonald and C. Innes (two vols, Bannatyne Club, Edinburgh, 1853), ii no. 130; Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis, ed. C. Innes (Bannatyne Club, 1837) [hereafter Moray Registrum], nos 164, 165 and 180; Miscellany of the Spalding Club (Aberdeen, 1842), ii 319; Illustrations of the Topography and Antiquities of the Shires of Aberdeen and Banff, vols ii–iv, ed. J. Robertson; vol. i, ed. G. Grub (Spalding Club, 1847, 1857, 1862, 1869), [hereafter Aberdeen-Banff Illustrations], iii 263. ↵

- ER iv 133, 212; National Library of Scotland [hereafter NLS], MS Adv 80.4.15, p 159 no 2, calendared by Alexander Grant, “Acts of Lordship: The Records of Archibald, Fourth Earl of Douglas,” in Freedom and Authority: Historical and Historiographical Essays Presented to Grant G Simpson, eds. Terry Brotherstone and David Ditchburn (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2000), 235–74, 259 (no 32). ↵

- W. Fraser, The Elphinstone Family Book (Edinburgh, 1897), ii no. 11. ↵

- Aberdeen-Banff Illustrations iv 181. ↵

- Calendar of the Laing Charters 854–1837, ed. J. Anderson (Edinburgh, 1899) [hereafter Laing Chrs], no. 81; Charters of the Abbey of Coupar Angus, ed. D. E. Easson (Scottish History Society, 3rd Series, 1947, henceforth Coupar Angus Chrs) ii no. 128; Laing Chrs no. 113; Charters of the Abbey of Inchcolm, ed. D. E. Easson and A. Macdonald (Scottish History Society, 3rd Series, 1938) [hereafter Inchcolm Chrs], no. 50. Cf. ER iv 425, 595, 634. ↵

- RMS ii no. 196. ↵

- Coupar Angus Chrs ii no. 128. ↵

- Inventory of Pitfirrane Writs 1230–1794, ed. W. Angus (Scottish Record Society, 1932, henceforth Pitfirrane Writs) no. 24. This is the only evidence that I have found linking justice ayres to Kinross, and it may be that the summons was for Kinross suitors to come to the court held at either Perth or (more probably) Cupar. Pitfirrane is in Fife, two miles west of Dunfermline, and it may be significant that Pitfirrane Writs nos 25–27 refer to the 1437 settlement of a dispute about the lands of Pitfirrane between David Halket of Pitfirrane and the abbot of Dunfermline. See also Registrum de Dunfermelyn, ed. C. Innes (Bannatyne Club, Edinburgh,1842) [hereafter Dunfermline Registrum] no. 406. The small sheriffdom of Kinross may not have generated enough of its own business to justify more than the very occasional visit by the justice ayre. ↵

- Fraser, Douglas iii no. 301. ↵

- See e.g. ER v 670; vi 62, 274, 333, 444, 447 (Annandale). ↵

- Registrum Episcopatus Brechinensis, ed. P. Chalmers and C. Innes (two vols, Bannatyne Club, Edinburgh, 1856), i, no. 61. ↵

- See also for the 1450s Alan R. Borthwick, “The King, Council and Councillors in Scotland, c.1430–1460,” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 1989), 193–4, 384. ↵

- ER vi 595. ↵

- ER vi 78. ↵

- ER vi 168, 177, 195, 200, 206, 209, 351, 353, 450, 546, 570, 641, 557, 201, 550. ↵

- ER vi 148, 97, 386, 174, 86, 143. ↵

- ER vi 485–6. ↵

- ER vi 158; Aberdeen-Banff Illustrations iv 205–13. ↵

- ER vii 226. ↵

- ER vii 281. ↵

- Muniments of the royal burgh of Irvine (2 vols, Ayrshire and Wigtonshire Archaeological Association, 1890–1) [hereafter Irvine Muniments], i no. 13. ↵

- Irvine Muniments, i no. 13. ↵

- Acta Dominorum Auditorum: The Acts of the Lords Auditors of Causes and Complaints, ed. T. Thomson (Edinburgh, 1839, henceforth ADA), 4. ↵

- ER viii 4–5. ↵

- RPS 1469/9. ↵

- ER viii 4. ↵

- ER viii 21. ↵

- ER viii 27. ↵

- ER viii 2, 3 (at Lauder). ↵

- ER viii 7 (at Jedburgh). ↵

- ER viii 10. ↵

- ER viii 12, 33–4, 36. ↵

- ER viii 36. ↵

- ADA, 12, 66. ↵

- RPS 1476/10/3; ADA, 57. ↵

- Irvine Muniments i no. 13. ↵

- Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, ed. T. Dickson and J. Balfour Paul (Edinburgh, 1877–1916, henceforth TA) i 6–10. ↵

- TA i 66, 68. ↵

- TA i 53. ↵

- ER viii 396, 480, 585; ADC i 14. For the constabulary of Haddington see The Sheriff Court Book of Fife 1515–22, ed. W. C. Dickinson (Scottish History Society, 3rd Series, 1928, henceforth Fife Court Bk.), 354–5. ↵

- Acta Dominorum Concilii, ed. T. Thomson G. Neilson, H. Paton and A. B. Calderwood (three vols, Edinburgh: Records Commission and H.M.S.O., 1839–1993) [hereafter ADC] i 26, 55, 79. ↵

- ER ix 380. ↵

- ER ix 460. ↵

- ADC i 233. ↵

- National Records of Scotland [NRS], Acta Dominorum Concilii, CS 5/16, f. 6. ↵

- See Norman Macdougall, James III, 2nd edn (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2009), chapters 7 and 8. ↵

- ADA, 98; Charters and documents relating to the burgh of Peebles, with extracts from the records of the burgh. A. D. 1165–1710 (Edinburgh: Scottish Burgh Records Society, 1872), no. 16. ↵

- NRS, State Papers, No. 19 (printed APS xii 33). For further context see Macdougall, James III, 222–3. ↵

- MacQueen, “Tame Magnates?” 111. ↵

- RPS 1488/1/15. ↵

- ADC iii 109. ↵

- NRS, JC 1/1, Records of the High Court of Justiciary, Court Books, Old Series 1493–1697. See further Jackson W. Armstrong, “The Justice Ayre in the Border Sheriffdoms, 1493–1498,” SHR 92, no. 1 (2013): 1–37. ↵

- ER x 366, 396. ↵

- TA i 130–1. ↵

- ER x 243. ↵

- TA i 140. ↵

- TA i 89. ↵

- TA i 93. ↵

- TA i 102–5, 150. ↵

- ADC i 165. Could this be the same ayre held at Kirkcudbright by John lord Drummond 8 May 1489 (Protocol Book of James Young, ed. Gordon Donaldson (Edinburgh: Scottish Record Society v. 74, 1952, henceforth Prot. Bk. Young, no. 210)? ↵

- TA i 130. ↵

- TA i 173. ↵

- TA i 173. ↵

- ER x 668. ↵

- ER x 366. ↵

- TA i 182. ↵

- TA i 184. ↵

- TA i 185. ↵

- TA i 200. ↵

- TA i 201. ↵

- ER x 396. ↵

- ER xi 336*, 337*. ↵

- NRS, JC 1/1, ff. 1r–17v. ↵

- TA i 237. ↵

- Prot. Bk. Young no. 725. ↵

- TA i 212, 238. ↵

- TA i 213. ↵

- TA i 239. ↵

- TA i 213–15, 240, 255–6; NRS, JC 1/1, ff. 18r–35v. ↵

- TA i 241. ↵

- ER xi 350*. ↵

- A Genealogical Deduction of the Family of Rose of Kilravock, ed. C. Innes (Spalding Club, 1848), 163. ↵

- ADA 118 (Peebles), 130 (Dumfries), 131 (Kirkcudbright), 149 (Peebles), 157 (Edinburgh), 174 (Ayr); ADC i 86 (Fife), 92–3 (Stirling), 111 (Ayr), 125 (Lauder), 149 (Dumfries), 155 (Jedburgh, Peebles), 166 (Dumfries), 226 (Ayr), 228 (Selkirk), 230 (Bervie), 233 (Kirkcudbright, Ayr), 258 (Ayr), 296 (Aberdeen), 303 (Jedburgh), 307, 309, 310, 315 (all Dumfries), 316 (Lanark), 337 (Dumbarton), 338 (Jedburgh), 351 (Dumfries), 363 (Wigtown), 366 (Aberdeen), 377 (Elgin), 394 (Kirkcudbright), 410 (Peebles), 412 (Dumfries); ADC ii 85 (Haddington), 288 (Dumfries), 313 (Perth); ADC iii 3 (Wigtown), 8 (Perth), 14 (Stirling), 21 (Renfrew), 81 (Elgin), 82 (Aberdeen, Elgin), 83 (Inverness), 101 (Edinburgh), 108 (two at Ayr), 111 (no location given), 124 (Jedburgh), 126 (Dumfries — ‘if held’), 127 (Jedburgh), 129 (Edinburgh), 134 (Stirling), 160 (Dumfries), 202 (Banff), 205 (Aberdeen), 243 (Edinburgh), 253 (Perth), 254 (Cupar), 266 (Dumfries), 267 (Dumfries), 277–8 (Jedburgh), 280 (Jedburgh), 285 (Jedburgh), 303 (Aberdeen), 318–19 (Wigtown), 330 (Ayr), 339 (Renfrew). On Renfrew as a barony within the sheriffdom of Lanark, then a sheriffdom within the Principality of Scotland, see Fife Court Bk., 364–5. ↵

- TA i 318; ER xi 316*, 333*; cf ADC ii 93–211 esp. at 210–11. ↵

- TA i 318. ↵

- ER xi 324*. ↵

- NRS, JC 1/1, ff 36r–47v. ↵

- ER xi 340*, 349*. ↵

- ER xi 324*, 353*. ↵

- ER i 18, mapped in Atlas of Scottish History to 1707, eds. Peter G. B. McNeill, and Hector L. MacQueen (Edinburgh: The Scottish Medievalists Conference, 1996), 195. ↵

- Fife Court Bk., 361. Inverbervie became a royal burgh c.1341 (RRS vi no 483; Pryde, Burghs, no 44; see further Penman, David II, 77–8). The former royal castle at Kincardine may have been rendered inoperative during the Wars of Independence and there is no record of any associated burgh. In 1345 David II granted the thanage of Kincardine with its castle and park to William earl of Sutherland and his wife Margaret Bruce (sister of the king) and their heirs in free barony (W. Fraser, The Sutherland Book (Edinburgh, 1892), iii, no 12). ↵

- For the rise of Dundee as an alternative centre in the sheriffdom of Forfar see E. P. D. Torrie, Medieval Dundee: A Town and its People (Dundee: Abertay Historical Society no. 30, 1990), 31–3. ↵

- Inchcolm Chrs no. 50. ↵

- See further Alice Taylor, The Shape of the State in Medieval Scotland, 1124–1290 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 230–3, 236–7. ↵

- ER i 9–10, 27. For analysis sceptical of the frequency of justice ayres at this period, see David Carpenter, “Scottish Royal Government in the Thirteenth Century from an English Perspective,” in New Perspectives on Medieval Scotland 1093–1286, ed. Matthew Hammond (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2013) 117–59, 133–7. ↵

- Raine, North Durham, no. 147. ↵

- Raine, North Durham, no. 326. ↵

- RRS vi no. 237; Melrose Liber ii no. 437. ↵

- See references above at n. 8. We must be careful here to distinguish the regular ayre towns from other places at which justice courts were held from time to time. Sometimes justice ayres were held in a sheriffdom’s dependent burghs, as with Edinburgh and Haddington, or Fife and Kinghorn, presumably because the locale was relevant to the business to be done in the court. Ad hoc justice courts were often held altogether outside the ayres: for example, on Largo Law in Fife, and at Aberchirder, Banffshire, and North Berwick, East Lothian, all cases of perambulations where the court met upon the marches in question (Dunfermline Registrum no. 590; Moray Registrum no. 203; Laing Chrs no. 113). For the forms of appointment of ad hoc justiciars see Scottish Formularies, ed. A.A.M. Duncan, (Edinburgh: Stair Society vol. 58, 2011), A9, A10, A25, B84, B85, E72, E73, E74, TCa 22, La 9. Other places off the usual circuits at which justice courts were held, seemingly in the open air, include Rayne in Aberdeenshire and Fowlis in Perthshire (Aberdeen Registrum i 79–81; HMC iii 417). Each of these was a case of crime, perhaps to be explained by the principle that a criminal court should be held where the wrong was committed (RPS 1436/10/13, a statute that, the RPS editors note, is found only in the ‘Black Acts’ printed in 1566). See also for the justiciar’s court at Rayne Oliver J. T. O’Grady, “The Setting and Practice of Open-air Judicial Assemblies in Medieval Scotland: A Multidisciplinary Analysis,” (PhD diss., University of Glasgow, 2008), esp. 131, 278–82, 335–6, 523; also ibid., 233–42 for the likely site of the Fowlis court at the “Hundhil” at Longforgan, although the example cited here is not mentioned. The other examples of later medieval open-air courts given by O’Grady seem generally to be those of baronies and other lower jurisdictions. Justiciary and sheriff courts were usually held in the tolbooths of the sheriffdom’s head burgh, while burgh courts generally met in their burgh tolbooths. ↵

- See Barrow, “Land Routes,” 52; also I. D. Margary, Roman Roads in Britain 3rd edn, (London: John Baker, 1973), 484–8 (roads 8f and g in the author’s numbering system); G. S. Maxwell, “The Evidence from the Roman Period,” in Loads and Roads, eds. Fenton and Stell, 22–48 at 27; Lawrence Keppie, The Legacy of Rome: Scotland’s Roman Remains 3rd edn (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2004), 108–26; Hardie, Roads of Medieval Lauderdale, chs 2–5. ↵

- Barrow, “Land Routes,” 53–4; Maxwell, “Roman Period,” 27; Keppie, Legacy of Rome, 118–20. ↵

- T. Reid, “Fords, Ferries, Floats, and Bridges near Lanark,” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (PSAS) 47 (1913) 209–56, 209; see further ibid., 217–23. Hyndford is one of a number of significant placenames in the area, which also include Howford, Tillieford and Crook Bait (i.e. Boat). The present bridge at Hyndford is an eighteenth-century construction. Bonnington Fall is today better known as the Falls of Clyde. ↵

- Barrow, “Land Routes,” 58 (citing the Gough Map of c.1360 or later; see now http://www.goughmap.org/); Margary, Roman Roads, 469–70 (road 78a); Keppie, Legacy of Rome, 98. Crawford was also the junction at which Roman roads coming up from Annandale and Nithsdale met and the Clyde was forded by the road heading north up the river’s east bank for Inveresk and Cramond: Margary, Roman Roads, 466–9 (road 7g); Keppie, Legacy of Rome, 98, 120–6. ↵

- Margary, Roman Roads, 465–6 (road 77); Maxwell, “Roman Period,” 27–8; Keppie, Legacy of Rome, 94–5, 96–100. ↵

- Keppie, Legacy of Rome, 96. ↵

- Barrow, “Land Routes,” 58 (again citing the Gough map); see further Marie Weir, Ferries in Scotland (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1988), 79, 82. Note that the shallowness of the Clyde estuary did at several points enable its fording by travellers at low tide up to the 17th century (ibid., 74). ↵

- See Atlas of Scottish History, 211. ↵

- Barrow, “Land Routes,” 51; Aberdeen before 1800: A New History, eds. E. P. D. Dennison, Ditchburn, and M. Lynch (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2002), 16–7. ↵

- See Weir, Ferries, 36–8; Aberdeen before 1800, 15–6. The Bridge of Dee was not completed until 1527. Torry was within the Arbroath abbey estate of Nigg, granted by William I (RRS ii nos 332, 513 (at 462)). ↵

- According to a noticeboard placed at the Visitors car park (visited 3 Jan. 2022), the modern footbridge over the Bervie Water below the town replaced stepping stones there in 1934. ↵

- For this see Weir, Ferries, 35–6; “Barrow, “Land Routes,” 60. The evidence for bridges at Marykirk in the 13th century (Arbroath Liber i no 144 – pontis de luffenoct [i.e. Luthnot] and pontem qui dicitur stanbrig – and see Barrow, “Land Routes,” 55 and n. 43) does not suggest either spanned the North Esk. For the grant of the royal Montrose-Ferryden ferry to Arbroath abbey from the late 12th century see RRS ii nos 228, 513 (at 463). ↵

- This route may also have traversed a former Roman road at least in part: Margary, Roman Roads, 494–5 (road 9b); see also Barrow, “Land Routes,” 58 (referring again to the Gough map for “a Strathmore route ... from Perth to Aberdeen”). ↵

- Where both Forfar and Dundee were visited in the course of a single ayre (see above, n. 32), use was probably made of a direct road between the two centres on the line of the A929. ↵

- Barrow, “Land Routes,” 58; Weir, Ferries, 35–8. Note also Arbroath Liber i no. 284 for “the king’s road leading to Forfar” (dated to the 13th century in Barrow, “Land Routes,” 55). For the Perth bridge see Harry G. R. Inglis, “The Roads and Bridges in the Early History of Scotland,” PSAS 47 (1913) 303–33, 322–4; L. Ross, and R. M. Spearman, “Watching Brief: Stanners Island (Kinnoul P) Medieval Bridge Footing, possible,” Discovery and Excavation Scotland (1982) 34–5; Ted Ruddock, “Bridges and Roads in Scotland: 1400–1750,” in Loads and Roads, eds. Fenton and Stell, 67–91, 81–2; Ewan, Townlife, 5, 52; “Perth Bridge,” Scotland’s Oldest Bridges, accessed 12 September 2024, https://scotlandsoldestbridges.co.uk/perth-bridge.html. ↵

- Weir, Ferries, 107–9. ↵

- For this route see Yeoman, Pilgrimage, 57; Tom Turpie, Report Detailing Historical References to Pilgrimage and the Cult of the Saints in Fife (2016), 20–1, published online at https://d1ssu070pg2v9i.cloudfront.net/pex/fcct/2019/08/05142329/Historical-Research-FPW-1.pdf. ↵

- For comparative evidence see Marjorie Nice Boyer, “A Day’s Journey in Mediaeval France,” Speculum 26 (1951), 597–609 (“Large parties very definitely contributed to a slow rate of speed ... most journeys were probably made at a rate between twenty and thirty miles [a day]”). ↵

- See above, text with n. 7. ↵

- On these medieval sheriffdoms, see Fife Court Bk., 362–4. ↵

- RMS ii nos 1110, 1752, 1852, 2742. Note also Annandale in the south: above, n.71. ↵

- RMS ii no. 163; W. Fraser, Memorials of the Montgomeries, earls of Eglinton (Edinburgh, 1859), ii no. 35. ↵

- RMS ii nos 1002, 1267; Alexander Grant, “Franchises North of the Border: Baronies and Regalities in Medieval Scotland,” in Liberties and Identities in the Medieval British Isles, ed. Michael Prestwich (Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, 2008), 155–99 at 171 n. 74. ↵

- RMS ii nos 1844 (office granted to Henry lord Sinclair for 13 years on 28 May), 1847 (office granted to Patrick Hepburn earl of Bothwell and John Hepburn prior of St Andrews, also for 13 years, on 29 May). ↵

- MacQueen, “Tame Magnates?” 96, citing RRS v no 389; Grant, “Franchises North of the Border,” 167–76. Mamore is the mountainous area between Glen Nevis and Loch Leven. ↵

- See above, text with n. 68. ↵

- See Borthwick and MacQueen, Law, Lordship and Tenure, 40–1, 52–4. ↵

- See Acts of the Lords of the Isles, 1336–1493, eds. Jean Munro and R. W. Munro (Edinburgh: Scottish History Society, 1986), xlii–l. The Lords of the Isles were also earls of Ross from c.1436 (ibid., xxxiv n. 54). ↵

- RPS 1504/3/16–20, 23. See also RPS A1504/3/118. ↵

- On this see further Stephen Boardman, The Campbells 1250–1513 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2006), 317–9. ↵

- Pacification of the Highlands and Islands was a recurring legislative theme in the later fourteenth century, however: see RPS 1369/3/5, 7; 1370/2/8; 1385/4/3; 1392/3/1. Legislation in 1425 asked the newly returned King James I to consider how to deal with the inability of “hieland men” who “reft and slew” each other to obtain full assythment for wrongs done to them, as in contrast happened in the (perhaps ironically dubbed) “law lands” (RPS 1425/3/26). ↵

- Barrow, Kingdom, 345, talks of “two main east-west passages across northern Scotland, the one which makes use of the Spey and Spean valleys,” and the other being the Great Glen. Other routes from west to east (or at any rate to the Crieff and Falkirk cattle trysts) are explored in A. R. B. Haldane, The Drove Roads of Scotland (1952, repr. Isle of Colonsay: House of Lochar, 1995), chs 4 (“The Drove Road from Skye and the Western Isles”) and 5 (“The Drove Roads of Argyll”), mapped in Atlas of Scottish History, 5. ↵

- Hector L. MacQueen, Law and Legal Consciousness in Medieval Scotland (Leiden: Brill, 2023), ch. 3, text with nn. 31–6. ↵

- See further Ranald Nicholson, Scotland: The Later Middle Ages (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1975), 544–7; Jane A. E. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 41–7. Christine Carpenter, “Political and Geographical Space: The Geopolitics of Medieval England,” in Political Space in Pre-industrial Europe, ed. Beat Kumin (Farnham and VT: Ashgate, 2009), ch 6, is suggestive on the analytical approaches that might be used to assess the later medieval Scottish situation. ↵

- RPS 1504/3/25, RPS A1504/3/124. Note too the comment of Barrow, Kingdom, 335 (“men of the late thirteenth century, when they thought of Kintyre, Argyll and the west coast generally, tended to associate these remote districts with the Isles”); perhaps this remained true at the beginning of the sixteenth century, although Dean Monro’s Description of the Occidental i.e. Western Isles of Scotland, written in 1549, makes only incidental mention of adjacent mainland regions. ↵

- See MacQueen, Law and Legal Consciousness, ch 3, text with nn. 86–90; ch. 8, text with nn 116–8. ↵