1 “She was the cause of the collapse of the entire Kingdom of the Isles”: Women, Reproductive Politics, and the Construction of History in the Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles

R. Andrew McDonald

[1102] [King Olaf Godredsson] had many daughters, one of whom married Somerled, ruler of Argyll; she was the cause of the collapse of the entire Kingdom of the Isles.

[c. 1223] … stimulated by bitterness and resentment, King Rognvald’s wife, Queen of the Isles, sowed the seeds of all the disharmony between Rognvald and Olaf.

— Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles (compiled ca. 1257)

For nearly two centuries, between 1079 and 1265, the Isle of Man in the middle of the northern Irish Sea basin lay at the heart of a transmarine kingdom that stretched from the Calf of Man to the Island of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides: the Kingdom of Man and the Isles. This far-flung realm was ruled by first one and later two vigorous dynasties of sea kings descended from the Hiberno-Norse warlord Godred Crovan, who conquered Man in 1079 and died on Islay in 1095. In the middle of the twelfth century the Kingdom fractured into two parts when Somerled of Argyll (d. 1164) wrested control of the Mull and Islay groups from Godred Crovan’s grandson. By the early 1260s, however, the maritime realms were hotly contested and their rulers increasingly squeezed between expansive monarchies in Scotland and Norway; following the turbulent events of 1263–65, the Treaty of Perth in 1266 formally ceded Man and the Isles to Scotland and marked the demise of the Kingdoms of Man and the Isles.[1]

The most important source for these medieval water worlds and their rulers is the mid-thirteenth-century Latin text known from its incipit as the Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles [Cronica regum Mannie et Insularum] (also known as the Manx chronicle), from which the passages quoted at the head of this essay are taken. The earliest surviving piece of indigenous historical documentation from the Isle of Man (excluding the corpus of carved stone memorials with inscriptions from the earlier Middle Ages), the Chronicles provides a brief, year-by-year account of significant events in the Isle of Man and the Hebrides from the year 1000 (correctly 1016) to the final entry in the year 1316. From the year 1047 (correctly 1066) the Chronicles provides unique information relating to the Isle of Man, its Norse-Gaelic ruling dynasty, and the connections of these kings with rulers in neighbouring lands, as well as the history of the Church, monasticism, and religious leaders in Man and the Hebrides. Production of the Chronicles began probably in the late 1250s at Rushen Abbey in the Isle of Man. Like most medieval chronicles it is anonymous, but a single scribe—almost certainly a monk of Rushen Abbey—wrote most of the text down to 1257; the narrative was then continued by several more scribes down to 1316. With its focus on the dynasty of Manx sea kings, this short text is full of vivid descriptions of rulers and other important figures, dramatic intrigues, plots, and rivalries worthy of Game of Thrones, as well as tantalizing glimpses into Manx and Hebridean society in this forgotten kingdom of the British Isles. At first glance, the Chronicles appears entirely male-dominated and devoid of a female presence: its compilers were primarily concerned with kings, warlords, battles, and politics, and the text therefore has the appearance of a dynastic chronicle designed to legitimize the status of the Manx kings.[2]

Closer examination of the Chronicles reveals an intriguing female presence, however. This paper highlights the hitherto largely neglected topic of women in the Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles, and poses some new questions concerning the dynamic interactions of gender, power, and historical writing in the medieval Kingdoms of Man and the Isles.[3] It pays particular attention to the intriguing problems raised by the brief excerpts above, where, at two separate places in the narrative—in the middle of the twelfth century and the early part of the thirteenth—the compiler of the text explicitly blames women for disasters that afflicted the Kingdoms. Although these Kingdoms were outwith the Scottish realm until their incorporation by the Treaty of Perth in 1266,[4] the subject of women in medieval and early modern Scotland comprises a central theme in much of Elizabeth Ewan’s pioneering work, and the present study is offered as a fitting tribute to her contributions in the field.[5]

There is nothing inherently surprising in the lack of a female presence in the Manx chronicle, of course. Most medieval texts are overwhelmingly male-dominated, and usually incorporate a degree of gender bias.[6] To take one example from many, the early thirteenth-century churchman and scholar Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis; d. ca. 1223), discussing the abduction of a rival’s wife by Diarmait Mac Murchada of Leinster (d. 1171), famously remarked in his Expugnatio Hibernica (ca. 1189) that “Almost all the world’s most notable catastrophes have been caused by women.” [7] Bearing in mind that the Manx chronicle was produced in an ecclesiastical context—at Rushen Abbey, a Cistercian house—it is only natural that it shares the general values and biases of the time. This is illustrated to good effect in the account of a miracle attributed to St Machutus around the year 1158. When the monastery of St Machutus came under threat of attack by the invading forces of Somerled, “The weaker sex, with dishevelled hair ran about the walls of the church, uttering lamentations and crying at the top of their voices, “Where are you now Machutus? … ”[8] Nevertheless, although women may be few and far between in its folios, a close reading of the text reveals that women play key roles. In fact, women’s roles as wives, mothers, and inciters are crucial to understanding some of the central themes of the text concerning succession politics, kin-strife, and what the compiler of the Chronicles lamented as “the cause of the collapse of the entire Kingdom of the Isles.” Thus, as Susan M. Johns has argued in a contemporary Welsh context, “placing women and gender at the heart of the analysis raises new questions about the construction of history.”[9]

Who are the women of the Chronicles? Excluding brief mentions of foreign rulers (such as the deaths of St. Margaret of Scotland in 1093, and of Queen Margaret of Scotland, sister of King Edward I of England, in 1274[10]) and one miracle attributed to the Blessed Virgin,[11] only five women are named in a Manx or Hebridean context in the Chronicles.

Affrica, the daughter of Fergus (d. 1161), the ruler of Galloway in southwest Scotland, married King Olaf Godredsson of Man (r. ca. 1113–53) sometime in the first half of the twelfth century. Their son was King Godred Olafsson (r. 1154–87). In its discussion of Olaf, the Chronicle observes that he “had many concubines from whom he begat three sons … and many daughters, one of whom married Somerled, ruler of Argyll,” an important statement to which we return below. [12]

Fionnula [Finnguala], described as “a daughter to MacLochlann, son of Muircheartach King of Ireland, and mother of Olaf [Godredsson],” was probably the daughter of Niall Mac Lochlainn, king of Cenél nEógain in the north of Ireland (1170–76).[13] Her marriage to King Godred Olafsson (d. 1187) in 1176 was conducted by a Papal Legate in the Isle of Man and was noted by the compiler of the Chronicles; this significant development is discussed further below.

Affrica Godredsdottir was the daughter of King Godred Olafsson (d. 1187). She married John de Courcy (d.c. 1219), the Anglo-Norman conqueror of Ulster, probably around 1180, though the date is nowhere recorded and represents a modern estimate.[14] The marriage is significant in terms of Hiberno-Manx relations in the wake of the arrival of the English in Ireland in the 1160s,[15] but Affrica herself remains relatively neglected. She is known principally as the founder, in 1193, of Grey Abbey in County Down, where an effigy traditionally held to be hers is of a later date, and she is known to have outlived her husband.[16]

Lauon (Lavon), described as the “daughter of a certain nobleman of Kintyre,” married Olaf Godredsson (d. 1237) around 1223. Lauon’s sister (who is not named—and more on her below) was married to Olaf’s brother and rival, King Rognvald Godredsson (d. 1229).[17] The fact that the Chronicles do not name her father is an interesting problem. Since the dominant family in Kintyre around the time of the events described included the descendants of Somerled of Argyll (d. 1164), the long-time rivals of the Manx kings, it is possible that Lauon’s father was a member of this rival kindred (perhaps Ruaidri the son of Ranald [Raghnall] the son of Somerled), and his name, accordingly, may have been excluded from the record for reasons of partisanship.[18] On the other hand, this is far from certain (our understanding of thirteenth-century landholding in Kintyre is vague at best[19]), and it is also possible that the chronicler simply did not know the name of her father.

After the bishop of the Isles declared Olaf Godredsson’s marriage to Lauon uncanonical and annulled it around 1223, Olaf subsequently married Christina, the daughter of Earl Ferchar of Ross in Scotland (d.c. 1251); Ferchar was a significant figure in the north-west highlands of Scotland in the reign of the Scottish king Alexander II (r. 1214–49).[20] It is an interesting question whether it was Christina or Lauon who was the mother of King Olaf’s son Harald, who succeeded him and died in a shipwreck in 1248. The Chronicles states that Harald was fourteen years old when he began to rule in 1237;[21] if correct, this would place his birth around the events of 1223, and would allow the possibility that he was the son of either Lauon or Christina. Given the manner in which Olaf’s marriage with Lauon seems to have been regarded as uncanonical, however, and given the concerns of the compiler of the chronicle with such matters (discussed below), it seems difficult to imagine that the chronicler would not have had something to say about it. Still, the issue is an intriguing one, and it is interesting that the Chronicles does not make an explicit statement about his maternity—particularly when it does make an explicit statement about the maternity of another ruler, King Olaf Godredsson (d. 1237).[22]

Several more unnamed women appear in the Chronicles. King Rognvald Godredsson’s (d. 1229) wife, Lauon’s sister, is described as “queen of the Isles” (regina Insularum). She is mentioned twice and named on neither occasion, and the reference to her as regina Insularum is unique in the text.[23] She is alleged to have incited the strife between the brothers Rognvald and Olaf around 1223 by sending a letter in King Rognvald’s name to his son Godred in the Isle of Skye, to the effect that Godred should kill his uncle Olaf.[24] Her culpability for these events and her namelessness in the Manx chronicle are important points which we shall analyze in greater detail below. Finally, there is an unnamed daughter of King Rognvald who seems to have been married to, or else was intended to be married to, the son of Alan, Lord of Galloway (d. 1234), as part of the political intrigues that marked the tumultuous conclusion to Rognvald’s reign.[25] This marriage was the catalyst that led to Rognvald’s expulsion by the Manx and to the eventual victory of Olaf in struggle with his brother.[26] Additionally, there are several mentions of unnamed concubines throughout the text—important references to which we will return below.

All of these women are defined solely in terms of matrimonial politics, expressed in their depiction as, first and foremost, wives and mothers. [27] The marriage alliances described by the text reflect the wide-ranging, kaleidoscopic, foreign relations of the Manx dynasty around the Irish Sea basin, cemented at various points in the dynasty’s history by unions with rulers in Galloway, Ireland, Ulster, Kintyre, and Ross.[28] The union of Fionnula with Godred Olafsson (d. 1187), for example, reflects the strong Irish links of the Manx dynasty in the first century or so of its existence, while the marriage of Godred’s daughter, Affrica, to the Anglo-Norman adventurer John de Courcy represents one way in which Manx interests in Ireland were radically reoriented in the decades following the English invasion of Ireland in the late 1160s.[29] The intriguing matrimonial politics of the brothers Olaf (d. 1237) and Ragnvald Godredsson (d. 1229) reflect not only the dynamics of the involvement of foreign powers like Scotland and Galloway in the civil war between the two brothers, but the marriage of Olaf Godredsson to a daughter of Ferchar of Ross also relates to the expansion of Scottish royal authority in the western seaboard.[30] Thus, at one level, these marriage alliances reflect the far-reaching foreign relations of the Manx dynasty.

Additionally, however, the Manx chronicle seems especially concerned with what might be described as “legitimate” as opposed to “illegitimate” marriages and unions. In particular, the theme of polygyny (a form of polygamy in which a man had a principal, official wife and one or sometimes even more secondary wives or concubines), frequently appears throughout the text.[31] The compiler of the Chronicles famously remarked upon King Olaf Godredsson’s (d. 1153) practice of keeping concubines that: “he was devout and enthusiastic in matters of religion…except that he over-indulged in the domestic vice of kings.”[32] As we shall see, this “domestic vice of kings” was regarded as having significant consequences for the history of the Kingdom. Moreover, despite the regularization of King Godred Olafsson’s (d. 1187), marriage by a papal legate in 1176, the practice evidently continued into the early thirteenth century. Godred’s son, King Olaf Godredsson (d. 1237), is said to have kept a concubine prior to his marriage to Lauon—one of her cousins, in fact.[33] Thus, the practice of concubinage recurs across nearly the entire history of the dynasty.

There was nothing unusual in this behaviour, which was practiced in many contemporary societies in Ireland, Wales, Scotland, the Hebrides, Norway, and elsewhere. Somerled of Argyll, for instance, said by the Chronicles to have married a daughter of King Olaf (d. 1153) and to have had four sons by her, is reputed in later Gaelic tradition to have had additional children from other unions, possibly born to concubines or the result of other marriages.[34] Such customs came increasingly under fire from the Church reformers of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, who regarded them, in the words of one modern scholar, as “outlandish, barbaric and utterly corrupt.”[35] The struggle for reform was very much an uphill one, however, and secular marriage persisted into the seventeenth century in Gaelic Ireland, Scotland, and elsewhere.[36] Similar complaints were registered by reformers about the matrimonial and sexual situation in contemporary Wales. The churchman and scholar Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis), for instance, listed incest, trial marriage, and inheritance by illegitimate sons among the less praiseworthy characteristics of the Welsh people,[37] although it appears that native matrimonial customs did not persist in Wales to the same degree that they did in Ireland and Scotland.[38]

These changing attitudes towards concubinage and illegitimate children are clearly evident and may be traced in the Manx chronicle. We have already noted the text’s condemnation of King Olaf for keeping concubines, and this attitude is shared in the account of the annulment of Olaf Godredsson’s marriage by Reginald, the bishop of the Isles in the 1220s, whose speech denounced the match as illegitimate.[39] An important turning point appears to have been a visit to the Isle of Man by the papal legate Cardinal Vivian in 1176–77, during which Vivian “caused king Godred Olafsson to be lawfully betrothed to his wife called Fionnula [Finnguala], a daughter to MacLochlann, son of Muircheartach king of Ireland, and mother of Olaf who was then three years old.”[40] The Cardinal’s Irish Sea itinerary is attested in other contemporary sources,[41] and the episode incidentally illuminates the status of the Manx kings as supporters of the ecclesiastical reforms of the twelfth century, as well as foreshadowing the even closer connections forged by Godred’s son, Rognvald, when he became a vassal of the papacy in 1219.[42]

A serious dynastic problem arising from the practice of polygyny was often a proliferation of sons by women of differing social status; this, in turn, led to frequent dynastic infighting and kin-feuds as members of the royal kindred (often brothers or half-brothers) struggled for political supremacy. [43] In Man and the Isles, the kingship was regularly contested among members of the royal kindred, from the death of the dynasty’s founder, Godred Crovan, in 1095, down to the last generation of his descendants in the 1250s; the episodes of kin-strife were outlined, sometimes in great detail, by the compiler of the Manx chronicle, for whom they formed a subject of considerable importance.[44] Briefly, there were major feuds among Godred Crovan’s sons between 1095 and the early twelfth century, and the end of the long reign of Godred’s son Olaf (r. 1113–53) was marked by his violent death at the hands of his nephews in 1153; Olaf’s son Godred then took revenge on the killers of his father in 1154. A few years later, the feuds took on another dimension when Somerled of Argyll (d. 1164), who had married a daughter of Olaf Godredsson by a concubine, seized control of Man, drove out King Godred Olafsson, and fractured the kingdom. In the later twelfth century, there were tensions between Godred’s sons Olaf and Rognvald in 1187—tensions which exploded into violent civil strife that sucked in neighbouring powers from 1223 until 1229/30, and to which we will return shortly. In 1230/31, Rognvald’s son Godred Don was slain in what looks like a continuation of the feud between his father and uncle, while in 1237 there was some sort of disturbance in the Isle of Man that may or may not have been related to these kin-feuds. The death of King Harald Olafsson in a shipwreck off Shetland in 1248 sparked a new round of dynastic struggles. Harald’s successor, his brother, Rognvald [Reginald], was assassinated in May of 1249, and a son of Godred Don named Harald seized the kingship. Harald was summoned to Norway by King Hakon IV Hakonarson (r. 1217–63) and is not heard from again, but the early 1250s in Man and the Isles were a turbulent time characterized by further struggles until King Magnus Olafsson (d. 1265), the brother of Harald and Rognvald, established himself in power about 1252–54. It is only at this point that the Manx chronicler notes that the hopes of his opponents were dashed and “they gradually faded away.”[45] The dynastic feuds were noteworthy for their duration, intensity, and bloody nature, but they also destabilized the kingdom and have been regarded as a source of weakness in the dynasty and the medieval Kingdoms of Man and the Isles.[46] In two instances the compiler of the Chronicles makes a direct link between reproductive politics and political fragmentation in the Kingdom, and it is to these episodes that our analysis will now turn.

The first instance occurred in the mid-1150s, with the rise of Somerled, styled by Irish annals on his death in 1164 as King of the Hebrides and Kintyre.[47] This is not the place for an extended discussion of Somerled’s origins and ancestry,[48] but the Manx chronicle relates how, soon after the establishment of King Godred Olafsson in power in 1154, Godred began “exercising tyranny against his chieftains.”[49] This prompted one of the disaffected chieftains to invite Somerled to send his son, Dugald, to be installed as king in the Isles. According to the Chronicles, Somerled allowed his son to be conducted through the Isles in what looks like a royal progress. King Godred, learning this, assembled a fleet and challenged Somerled, with the resulting battle fought at an unstated location on the night of the Epiphany in 1156 causing “much slaughter on both sides.” The Chronicles comment that, “When day dawned they made peace and divided the Kingdom of the Isles between them. The kingdom has existed in two parts from that day up until the present time, and this was the cause of the break-up of the kingdom from the time the sons of Somerled got possession of it.”[50]

An earlier entry in the Chronicles provides vital context for understanding this important episode. In its account of King Olaf Godredsson and his reign that begins under the year 1102, the chronicler provides the crucial information that Somerled had married a daughter of King Olaf by one of his concubines: “he [King Olaf] had many concubines from whom he begat three sons … and many daughters, one of whom married Somerled, ruler of Argyll.”[51] King Godred Olafsson, whom Somerled challenged in the late 1150s, was therefore Somerled’s brother-in-law, and it is possible to view the episode within the framework of kin-feuds that so fascinated the compiler of the chronicler. Moreover, it is striking that, in its earlier account of King Olaf’s matrimonial and reproductive politics, the chronicler explicitly blames this unnamed woman for the division in the kingdom: “she was the cause of the collapse of the entire Kingdom of the Isles.”[52] Is this, perhaps, why she goes unnamed by the chronicler?[53] Whatever the case, it is interesting to observe that there is a clear connection made by the chronicler between the matrimonial and reproductive politics of the Manx kings and the fragmentation of the kingdom, which endured down to the time the Chronicles was being compiled (the 1250s). In fact, the date of the compilation of the chronicle in the 1250s (probably around 1257) may be directly relevant here, since the early 1250s witnessed a renewed period of struggle between the Manx and Somerledian lines. The Manx chronicle relates that, in 1250, when Magnus son of Olaf and one of Somerled’s descendants, called “John son of Dougal” (correctly John [Ewen] son of Duncan of Argyll [d. c. 1268]), arrived in Man, the latter’s arrogant behavior alienated the Manx and led to a skirmish at St. Michael’s Isle, in which many of John’s [Ewen’s] followers were slain or drowned while fleeing to their ships.[54] It is therefore possible that the subject of the original splitting of the kingdom in the 1150s struck a chord with the compiler of the chronicler a century later, in the wake of the events of the early 1250s. Certainly the fracture of the kingdom resonated with contemporaries, as evidenced by the chronicler’s remark about King Godred’s defeat by Somerled in 1156 that “the kingdom has existed in two parts from that day up until the present time … ”[55]

The second instance of an episode in which the political fragmentation of the Kingdom is blamed on a woman relates to the most intensive period of internecine rivalry in the history of the entire dynasty: that between the brothers Rognvald and Olaf in the early thirteenth century. The chronicler begins his discussion: “For the benefit of the readers it is considered not out of place now to relate briefly something about the deeds of the brothers Reginald and Olaf.”[56] It has been suggested that this narrative device is utilized with the intent of emphasizing the significance of the episode within the text—something that is further supported by the positioning of the episode at nearly the mid-point of the Chronicles, as well as by its significant length: it represents about fifteen percent of the total length of the text.[57] The episode also represents the most detailed portion of the text, which suggests that the compiler was an eyewitness, had first-hand information, or was perhaps relying on a detailed narrative account that no longer survives.

The foundation for the struggle was laid in the reign of King Godred Olafsson (d. 1187). Godred—perhaps in an attempt to stabilize the succession following his own experience in 1153/54—had made provision that his younger son Olaf should succeed him, since he was said to have been “born in lawful wedlock” (discussed below). The Chronicles relates, however, that, upon Godred’s death, the Manx instead chose Olaf’s elder brother Rognvald as king, since he was “a sturdy man and of maturer years,” while Olaf was said to have been only ten years of age. Upon taking up the kingship, Rognvald granted his brother the island of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides.[58] When Olaf approached Rognvald for a larger share of the kingdom, Rognvald had him arrested and sent to King William I of Scotland (r. 1165–1214), who imprisoned him; this reference places the period of his captivity between about 1207 and late 1214 or early 1215, since William died on 4 December 1214.[59] Following his release, Olaf undertook a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostella, from which he returned an undisclosed time later to be received peaceably by Rognvald, who then prevailed upon his brother to marry the daughter of a “certain nobleman from Kintyre” named Lauon, the sister of Rognvald’s own wife. Olaf was again granted the Isle of Lewis and went off to live there. Not long after Olaf had settled in Lewis, however, Reginald, the Bishop of the Isles (d. c. 1226), informed Olaf that his recently-contracted marriage was illicit, because Olaf had previously been married to the first cousin of his wife. Bishop Reginald assembled a synod and annulled the marriage between Olaf and Lauon; Olaf then wedded Christiana, the daughter of Ferchar Maccintsacairt, either already, or soon to be, styled earl of Ross, an important figure in the north-west of Scotland who was closely aligned with the Scottish king Alexander II (1214–49).[60]

These events so angered Rognvald’s wife, Lauon’s sister, that she “sowed the seeds of all the disharmony between Reginald and Olaf.”[61] She did this by sending a letter secretly under King Rognvald’s seal to his son Godred in the Isle of Skye, instructing him to kill Olaf. Godred duly collected an army and went to Lewis, but Olaf eluded him and escaped in a small boat to the court of his father-in-law in Ross. Meanwhile, a disaffected official, Paul, son of Boke, the sheriff of Skye, defected from Godred and joined Olaf in exile in Ross where he and Olaf entered into an alliance. Olaf and Paul returned to Skye, gathered support, and ambushed Godred at a “certain island called the isle of St. Columba,” the exact location of which is disputed.[62] Whatever the location, Godred’s supporters were cut down and he himself was taken, blinded, and castrated (though he apparently survived). These events took place in the year 1223.

The next year, 1224, Olaf came to Man and landed at Ronaldsway. The Chronicles relate that Rognvald and Olaf divided the kingdom between them, but the division was short-lived, and by 1226 Rognvald found himself ousted entirely, living in exile at the court of Alan, Lord of Galloway (d. 1234). The final acts of the feud were played out in the winter of 1228–29. An invasion of the Isle of Man by Alan and Rognvald was repelled by Olaf, and so a second invasion was orchestrated in January 1229 in which Rognvald attacked and burned Olaf’s ships at Peel and managed to gain enough support in the island to force a showdown with his brother. On the fourteenth day of February, the two brothers with their respective armies met at Tynwald, the ancient assembly-centre for the annual Þing and the ceremonial heart of the Island. The meeting near this important site suggests that a parley or negotiation may have been intended, although the outcome was a battle in which Rognvald’s army was defeated and Rognvald himself was slain.[63]

Even the death of Rognvald and the seeming triumph of Olaf failed to end the feud, however, which resonated for another twenty years, down to the early 1250s. Rognvald’s son, Godred Don, was slain in what looks like a continuation of the strife in Lewis in 1230/31,[64] while Godred Don’s son Harald seized the kingship following the assassination of King Reginald/Rognvald in 1249 in circumstances that have led to suspicions about his complicity in the new king’s killing. The Chronicles regarded Harald unfavourably[65] and, as an illustration of Harald’s alleged tyranny, present a miracle story in which the Blessed Virgin Mary helps a chieftain named Donald, who had been persecuted by Harald, escape from incarceration.[66] It was only in the early 1250s that the threat from King Rognvald’s line seems to have evaporated.

It is noteworthy that the compiler of the Chronicles elucidates the causes of the feud between the brothers very clearly in this section of the text, and these return us to questions of marriage, concubinage, and (for the compiler of the text) the evil nature of women. The cause of the feud was the annulment of Olaf’s marriage to Lauon, and his subsequent marriage to Christina, both of which were enforced by Bishop Reginald. Moreover, the catalyst of the feud was the actions of King Rognvald’s wife, Lauon’s sister, who took matters into her own hands and sent a letter in her husband’s name to her son, Godred, ordering him to kill Olaf. Indeed, the chronicler remarks bluntly that “stimulated by bitterness and resentment, King Reginald’s [Rognvald’s] wife, Queen of the Isles, sowed the seeds of all the disharmony between Reginald [Rognvald] and Olaf;” further judgment is evident in the characterization of these actions as the “wicked wish” of the Queen.[67]

This passage also probably helps to resolve the intriguing puzzle mentioned near the outset of the paper as to why Rognvald’s wife is nowhere named in the Chronicles. This omission is as curious as it is significant. The compiler of the Chronicles cannot have been ignorant of her identity since he knows the names of Olaf’s two wives, as well as the name of King Godred’s principal wife, Fionnula; moreover, the events occurred within living memory of the inception of the chronicle in the late 1250s, and it is therefore very difficult to believe that the name of this Queen of the Isles was unknown when so many other notable women of the dynasty are named within the pages of the text. Names are important, and this un-naming therefore has the appearance of a campaign to remove from history the identity of the woman who was considered responsible for the “disharmony” between brothers that characterized the 1220s in the Isle of Man: a case of medieval Manx damnatio memoriae, a condemnation of memory and a form of dishonour which sought to erase someone from history. If this was in fact the intent of the scribe, then his effort was successful, for, as strange as seems, no trace of the name of Rognvald’s wife appears to survive: she was a victim of what has been described as the “propaganda and character assassination” that often accompanied contemporary succession politics.[68] Such manipulation of memory relating to female members of dynasties is not as far-fetched as it may seem. J. Beverley Smith remarks, in a near-contemporary Welsh context concerning the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (d. 1282), that “the genealogists, who so meticulously recorded the affiliations of a multitude of other men, failed to retain a memory of the name of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s mother.”[69] Susan M. Johns suggests that this omission demonstrates the manner in which social memory could be gendered from its inception, but neither Smith nor Johns goes so far as to ascribe it to a deliberate campaign of damnatio memoriae as I am suggesting transpired in this instance.[70]

The Manx chronicler, then, places the responsibility for the feud squarely on the wicked wish of the unnamed queen. But is it possible there was another underlying factor at play? Is it possible that the status of Rognvald and Olaf as sons of Godred by different mothers was the elephant in the room? To begin, the Chronicles inform us that, at the time of Godred’s death in 1187, Rognvald was “a sturdy man of maturer years” while Olaf was only ten years old. Olaf, however, had been appointed in Godred’s lifetime to succeed him in the kingship, “as this inheritance was his by right, for he had been born in lawful wedlock,” and, indeed, the chronicle states specifically that his mother was the Irish princess Fionnula when it mentions her marriage to King Godred in 1176.[71] When Godred died, however, the Manx people chose Rognvald as king, since he was older and more experienced than Olaf. This, says the chronicler, “was why the Manx people established Reginald [Rognvald] as their king.”[72] But there are problems here. The reference to Olaf having been born in lawful wedlock and the inheritance being his by right must be considered in the context of the formalization of Godred’s marriage to Fionnula by the Papal Legate Cardinal Vivian in 1176: if Rognvald, the elder brother, had been born before this, he may have been regarded as illegitimate. Olaf, however, may have been acceptable because he was born either just before or immediately following the settlement.[73] There is some contradictory information concerning Olaf’s age, however: he is said to have been three years old at the time his father married Fionnula in 1176, but in 1187 he is said to have been ten years old.[74]

Another problem relates to the identity of Rognvald’s mother. While the Manx chronicle makes explicit mention of Olaf’s mother—Fionnula [Finnguala]—nowhere is the identity of Rognvald’s mother mentioned, which again seems unusual in light of the information provided by the chronicler on the parentage of Olaf. Some evidence points in another direction, so perhaps the omission is important. In an Irish praise poem, probably contemporary with the first half of his reign, King Rognvald is addressed in two places as “macSadhbha,”[75] apparently indicating that his mother’s name was Sadhbh—perhaps an otherwise unknown Irish concubine or wife of Godred, but certainly not a detail that a good poet would have gotten wrong.[76] This is possible in light of the Irish connections of not only Godred but his father Olaf as well. There is also a fragmentary letter from Rognvald’s brother Olaf to King Henry III of England, dated circa 1228, in which Olaf describes his brother as a bastard, but does not refer to the identity of Rognvald’s mother. [77] Given the intense conflict that existed between the two brothers over the kingship at that time and the partisan nature of the document, this could just as easily be intended as a slur on Rognvald’s claim to the kingship as an indication that he was the son of an irregular (from the point of view of the Church) relationship with a concubine. In the end, no firm conclusion about the identity of Rognvald’s mother is possible, but the weight of evidence is convincing to indicate that she was of Gaelic, likely Irish, stock. It must remain an open question whether she was Finnguala or else the Sadhbh of the praise-poem, although there is a strong possibility that she was the latter.[78]

If Rognvald and Olaf were sons of Godred by different mothers, this might explain the intensity of the struggle between the two brothers, and their apparent hatred for one another. Bart Jaski has suggested that, in the contemporary Irish context, tensions between half-brothers could be shaped by the political background, social status, and reputation of their respective mothers. Jaski adds: “the sources are silent about intrigues at court, the vying for power, the scheming behind the scenes, the competition between queens and concubines and other personal and political games which often form the icing on the cake in historical writing.”[79] Pauline Stafford has remarked upon the manner in which nearly contemporary succession politics in England (mid-tenth to mid-twelfth centuries), “produced a hotbed of gossip, intrigue, and suspicion. Issues of birth, and thus of marriage, are frequently aired, especially at a time when reforming ecclesiastical views are focusing attention on the definition of marriage itself. Women, as the wives and mothers of claimants, are natural targets … ”[80] Reading the Manx chronicle with an eye to gender therefore reveals, among other things, the intriguing intersection of matrimonial and reproductive politics with the construction of history in the medieval Kingdom of Man and the Isles.

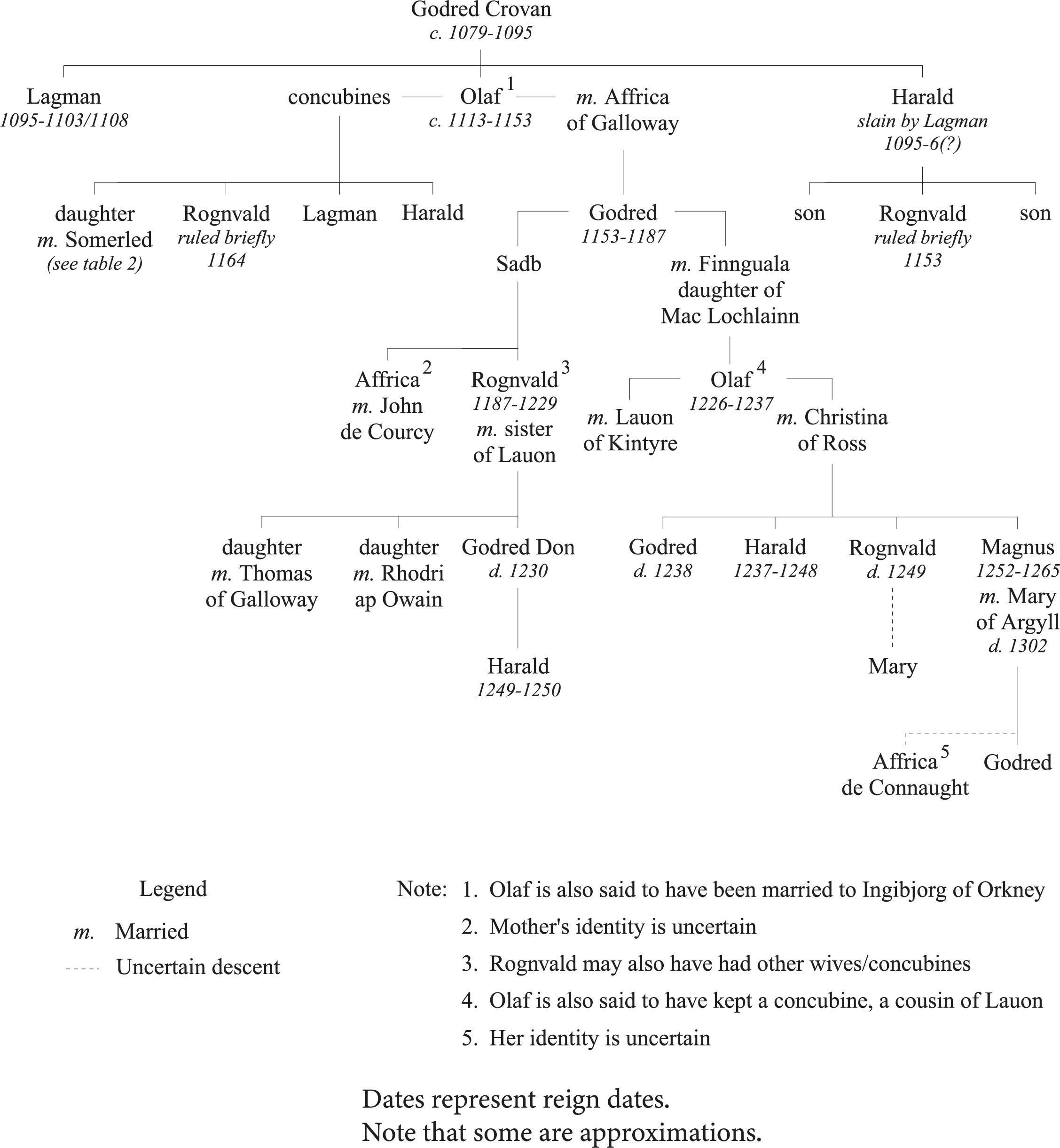

Figure 1.1: The Crovan Dynasty, c.11th–14th centuries

- The author is grateful to Angus A. Somerville and Benjamin T. Hudson for discussion of the topic on many occasions and for commenting on parts of the essay; he is also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. Special thanks to Loris Gasparotto and Christina Gleave for producing the genealogical table at the end of this chapter.

A recent survey is R. A. McDonald, The Sea Kings: The Late Norse Kingdom of Man and the Isles c. 1066–1275 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2019); see also S. Duffy and H. Mytum, eds., A New History of the Isle of Man Volume III: The Medieval Period 1000–1406 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015). The orthography of personal names presents a significant challenge in a study such as this, since names take different forms depending on the language of the original document and there are no well-established scholarly norms. I here use Anglicized forms of names, while recognizing that this will inevitably not please all readers. Note that although the Norse form Rognvald is utilized here (as in King Rognvald Godredsson, d. 1229), when the name appears as Reginald(us) in the Manx Chronicle, I allow the form “Reginald” to stand in the translation. There is a useful concordance of personal names in Duffy and Mytum, eds., New History of the Isle of Man Volume III, 3. ↵

- A full digital facsimile of the entire manuscript is accessible on the British Library’s Digitised Manuscripts Website (http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Cotton_MS_julius_a_vii); the most recent edition and translation is Cronica Regum Mannie et Insularum. Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles BL Cotton Julius Avii, ed. and trans. G. Broderick, 2nd ed. (Douglas, 1995) [hereafter CRMI]; this edition is used throughout, cited by folio number. On the Chronicles see B. Williams, “The Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles,” in New History of the Isle of Man Volume III, 305–28; and McDonald, Sea Kings, ch. 2. Rushen Abbey was founded by King Olaf Godredsson as a Savignac house in 1134, but with the absorption of the Savignacs into the Cistercian Order in 1147, Rushen also changed its affiliation: see P. J. Davey, “Medieval Monasticism and the Isle of Man c. 1130–1540,” in New History of the Isle of Man Volume III, 349–76. ↵

- Some of which were originally developed in R. A. McDonald, Kings, Usurpers, and Concubines in the Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019). ↵

- The Acts of Alexander III King of Scots, 1249–86, ed. C. J. Neville and G. G. Simpson (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 2012), no. 61; abridged translation in Scottish Historical Documents, trans. G. Donaldson (London, 1970, repr. Glasgow, 1997), 34–7. ↵

- See, e.g., E. Ewan and M. Meikle, eds., Women in Scotland c.1100–c.1750 (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 1999, 2000); E. Ewan, R. Pipes, J. Rendall, and S. Reynolds, eds., The New Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women, 2nd ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018). ↵

- M. Bull, Thinking Medieval: An Introduction to the Study of the Middle Ages (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 77; for the possibilities of the sources, see K. L. French, “Medieval Women’s History: Sources and Issues,” in Understanding Medieval Primary Sources: Using Historical Sources to Discover Medieval Europe, ed. J. T. Rosenthal (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), 196–209. ↵

- Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales), Expugnatio Hibernica: The Conquest of Ireland, ed. and trans. A. B. Scott and F. X. Martin (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1978), 24–5; Giraldus added that, “No doubt she was abducted because she wanted to be and, since ‘woman is always a fickle and inconstant creature,’ she herself arranged that she should become the kidnapper’s prize.” ↵

- CRMI, f. 38v. ↵

- S. M. Johns, Gender, Nation and Conquest in the High Middle Ages: Nest of Deheubarth (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), 229. ↵

- CRMI, f. 33v, f. 49v. ↵

- CRMI, f. 47v–48r. ↵

- CRMI, f. 35v. A late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century summary of Norwegian kings’ history relates that Olaf married Ingibjorg, the daughter of Hakon Paulsson, earl of Orkney (c. 1103–23): Ágrip ap Nóregskonunga Sögum: Fagrskinna – Nóregs Konunga Tal, ed. B. Einarsson (Reykjavik: Íslenzka fornritafálag, 1985), 373. Perhaps the Manx chronicle regarded her as a concubine rather than a canonical wife. ↵

- CRMI, f. 40r; F. X. Martin, “John, Lord of Ireland, 1185–1216,” in New History of Ireland, volume II: Medieval Ireland, 1169-1534, ed. A. Cosgrove (Oxford: OUP, 1987), 135. ↵

- CRMI, f. 41r; Giraldus Cambrensis, Expugnatio Hibernica, 180-81. On De Courcy see, inter alia: S. Duffy, “The First Ulster Plantation: John de Courcy and the Men of Cumbria,” in Colony and Frontier in Medieval Ireland: Essays Presented to J. F. Lydon, eds. T. B. Barry, R. Frame, and K. Simms (London: Bloomsbury, 1995), 1–28; S. Flanders, De Courcy: Anglo-Normans in Ireland, England and France in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2008). ↵

- R. A. McDonald, Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting 1187–1229: King Rögnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2007), 125–28; R. A. McDonald, “Man, Ireland, and England: the English Conquest of Ireland and Hiberno-Manx Relations,” in Medieval Dublin Vol. VIII, ed. S. Duffy (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2008), 131–49. ↵

- CRMI, f. 41r; J. Hunt and P. Harbison, Irish Medieval Figure Sculpture, 1200–1600, 2 vols (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1974), i, 133–34 and ii, plate 22; J. Otway-Ruthven, “Dower Charter of John de Courcy’s Wife,” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 12 (1949): 77–81. ↵

- CRMI, f. 42r. ↵

- See A. Woolf, “The Age of Sea-Kings: 900–1300,” in The Argyll Book, ed. D. Omand (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2004), 94–109 at 107. ↵

- See e.g. R. A. McDonald, The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland’s Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c.1336 (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 1997), 83–5; and Woolf, “Age of Sea-Kings: 900–1300,” 105–08. ↵

- CRMI, f. 42v. On Ferchar see R. A. McDonald, “Old and New in the Far North: Ferchar Maccintsacairt and the Early Earls of Ross, c.1200–74,” in The Exercise of Power in Medieval Scotland, c. 1200–1500, eds. S. Boardman and A. Ross (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2003), 23–45. Christina is discussed in E. Sutherland, Five Euphemias: Women in Medieval Scotland 1200–1420 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999), 63–8, where her status as queen of the Isles is highlighted. ↵

- CRMI, f. 44v. ↵

- CRMI, f. 40r. ↵

- See note 69 below. ↵

- CRMI, f. 42v. ↵

- CRMI, f. 44r ↵

- Another daughter of Rognvald was married to the Prince of Gwynedd, Rhodri ap Owain, sometime before his death in 1195, but this match is unremarked upon by the Manx chronicle: McDonald, Manx Kingship, 103–05. ↵

- A treatment of the topic in an Irish Sea/Scottish context is R. A. McDonald, “Matrimonial Politics and Core-Periphery Interactions in Twelfth- and Early Thirteenth-Century Scotland,” Journal of Medieval History 21 (September 1995): 227–47. See also H. B. Clarke, “The mother’s tale,” in Tales of Medieval Dublin, eds. S. Booker and C. N. Peters (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2014), 52–62. ↵

- See, e.g., McDonald, Manx Kingship and Sea Kings, passim; R. Oram, The Lordship of Galloway (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2000), 68–73, 92, 104–05; Woolf, “Age of Sea-Kings: 900–1300,” 106–7. ↵

- McDonald, “Man, Ireland, and England,” 131–49. ↵

- Woolf, “Age of Sea-Kings: 900–1300,” 107; N. Murray, “Swerving from the Path of Justice: Alexander II’s Relations with Argyll and the Western Isles, 1214–1249,” in The Reign of Alexander II, 1214–49, ed. R. Oram (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2005), 285–305. ↵

- See D. Ó Corráin, “Women in Early Irish Society,” in Women in Irish Society: the Historical Dimension, eds. M. MacCurtain and D. Ó Corráin (Dublin: Arlen House, The Women’s Press, 1978), 1–13; B. Jaski, “Marriage Laws in Ireland and on the Continent in the Early Middle Ages,” in ‘The Fragility of Her Sex’? Medieval Irish Women in their European Context, eds. C. Meek & K. Simms (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1996), 16–42; A. Candon, “Power, Politics and Polygamy: Women and Marriage in Late Pre-Norman Ireland,” in Ireland and Europe in the Twelfth Century: Reform and Renewal, eds. D. Bracken & D. Ó Riain-Raedel (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2006), 106–27. For a Norwegian context see J. Jochens, “The Politics of Reproduction: Medieval Norwegian Kingship,” American Historical Review 92 (1987): 327–49. An important study dealing with the early medieval period is P. Stafford, Queens, Concubines and Dowagers: The King’s Wife in the Early Middle Ages (University of Georgia Press, 1983), see esp. 62–79. ↵

- CRMI, f. 35v. ↵

- CRMI, f. 42r–42v. ↵

- “History of the MacDonalds,” in Highland Papers, vol. 1, ed. J. R. N. MacPhail (Edinburgh: Printed for the Scottish History Society, 1914), 5–72, at 11; discussion in W. D. H. Sellar, “Marriage, Divorce and Concubinage in Gaelic Scotland,” Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness 51 (1978–80): 464–93; McDonald, Kingdom, 45, 69. ↵

- D. Ó Corráin, “Marriage in Early Ireland,” in Marriage in Ireland, ed. A. Cosgrove (Dublin: College Press, 1985), 5–24 at 21. See the important evidence provided by The Letters of Lanfranc Archbishop of Canterbury, ed. and trans. H. Clover and M. Gibson (Oxford: OUP, 1979), nos. 9 (to Guthric), 10 (Toirrdelbach); no. 8 displays the concern of Pope Gregory VII with Irish marriage and sexual practices. ↵

- D. Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, 400–1200 (London: Longman, 1995), 127; Sellar, “Marriage, Divorce and Concubinage in Gaelic Scotland,” 464–93 at 473. ↵

- Gerald of Wales, The Journey Through Wales and The Description of Wales, trans. L. Thorpe (London: Penguin, 1978), 262–4, 273; these comments ought to be viewed through the lens of Gerald’s attitudes toward the Welsh and Irish peoples, however: see J. Gillingham, “The Beginnings of English Iimperialism,” Journal of Historical Sociology 5,4 (1992): 392–409; reprinted in The English in the Twelfth Century: Imperialism, National Identity, and Political Values (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2000), 3–18. ↵

- H. Pryce, Native Law and the Church in Medieval Wales (Oxford: OUP, 1993), ch. 4; see also R. R. Davies, “The Status of Women and the Practice of Marriage in Late Medieval Wales,” in The Welsh Law of Women, eds. D. Jenkins and M. Owen (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1980), 93–114, esp. at 106–08, which deals for the most part with the later medieval period. ↵

- CRMI, f. 42r–42v. ↵

- CRMI, f. 40r. ↵

- Giraldus Cambrensis, Expugnatio, 174–75, 180–81 and notes on 332–3; P. C. Ferguson, Medieval Papal Representatives in Scotland: Legates, Nuncios, and Judges-Delegate, 1125–1286 (Edinburgh: The Stair Society, 1997), 53–5. ↵

- Vetera Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum Historiam Illustrantia, ed. A. Theiner (Rome, 1864; repr. Osnabrück, 1969), no. 26, p. 11; translated in Monumenta de Insula Manniae, or a Collection of National Documents Relating to the Isle of Man, ed. and trans. J. R. Oliver (3 vols, Douglas: Printed for the Manx Society, 1860–2), ii, 52–7; discussion in McDonald, Manx Kingship, 143–52. ↵

- R. Frame, The Political Development of the British Isles, 1100–1400 (Oxford: OUP, 1990), 112; Gillingham, English in the Twelfth Century, 16. ↵

- Dynastic strife is analyzed in more detail in McDonald, Manx Kingship, ch. 2, and R. A. McDonald, “‘Disharmony between Reginald and Olaf’: the Feud between the Sons of Godred II and Kin-strife in the Kingdom of Man and the Isles,” in Familia and household in the Medieval Atlantic Province, ed. B. T. Hudson (Tempe: ACMRS Press, 2011), 155–75. ↵

- CRMI, f. 49r. ↵

- D. Carpenter, The Struggle for Mastery. Britain 1066–1284 (London, 2003), 117. An important work on feuding in a British context is J. Gillingham, “Killing and Mutilating Political Enemies in the British Isles from the Late Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century: a Comparative Study,” in Britain and Ireland 900–1300: Insular Responses to Medieval European Change, ed. B. Smith (Cambridge: CUP, 1999), 114–34. ↵

- Annals of Tigernach, 1164.6: https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T100002A/index.html ↵

- See W. D. H. Sellar, “The Origins and Ancestry of Somerled,” Scottish Historical Review 45 (1966): 123–42; A. Woolf, “The Origins and Ancestry of Somerled: Gofraid mac Fergusa and ‘The Annals of the Four Masters’,” Mediaeval Scandinavia 15 (2005): 199–213. ↵

- CRMI, f. 37v. ↵

- CRMI, f. 37v; see n. 56 below. ↵

- CRMI, f. 35v; see n. 53 below. ↵

- CRMI, f. 35v: Accepit autem uxorem affricam nomine filiam fergus de galwedia de qua genuit godredum habuit & concubinas plures de quibus filios tres scilicet, reignaldum, lagmannum & haraldum & filias multas generauit. Quarum una nupsit sumeledo regulo herergaidel que fuit causa ruine totius regni insularum. ↵

- Orkneyinga saga, composed in the early thirteenth century, named Olaf’s daughter, Somerled’s wife, as Ragnhild, though its information on Somerled must be treated with caution: Orkneyinga Saga: the History of the Earls of Orkney, trans. H. Pálsson and P. Edwards (London: Penguin, 1981), 208. See the pertinent comments of J. H. Barrett, “Svein Asleifarson and 12th-century Orcadian society,” in The World of Orkneyinga Saga, ed. O. Owen (Kirkwall: Orkney Islands Council, 2005), 213–23 at 216. ↵

- CRMI, f. 48r–48v. ↵

- CRMI, f. 37v. factumque est regnum biparititum a die illa usque in presens tempus, & hec fuit causa ruine regni insularum ex quo filii sumerledi occupauerunt. ↵

- CRMI, f. 41v. ↵

- McDonald, Manx Kingship, 98–9. ↵

- CRMI, f. 41v ↵

- Early Sources of Scottish History AD 500–1286, ed. and trans. A. O. Anderson (2 vols. Edinburgh, 1922; repr. Paul Watkins Publishing, 1990) ii, 398 n. 5. ↵

- McDonald, “Old and New in the Far North,” 23–45. ↵

- CRMI, f. 42v; see n. 68 below. ↵

- CRMI, f. 43r. Tiny Skeabost Island on the Isle of Skye, a few hundred metres above the mouth of the River Snizort, and Eilean Chaluim Chille in Kilmuir, which until the eighteenth century lay in the middle of the now drained Loch Chaluim Chille, are leading candidates: Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions of Scotland, Ninth Report, With Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the Outer Hebrides, Skye and the Small Isles (Edinburgh, 1928), no. 616; W. D. H. Sellar, “The Ancestry of the Macleods Reconsidered,” Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, 60 (1997–1998): 233–58; S. Thomas, “From Cathedral of the Isles to Obscurity—the Archaeology and History of Skeabost Island, Snizort,” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 144 (2014): 245–64 at 259. ↵

- CRMI, f. 44r. ↵

- There is, however, some doubt as to whether this is the same Godred who was incited to attack his uncle Olaf in 1223; the epithet “Don” (‘Brown’) used in the chronicle for the events of 1230 is not applied to the Godred of 1223. Either Godred survived the attack of 1223, or else Rognvald had two sons named Godred: see McDonald, Sea Kings, 149–50. ↵

- CRMI, f. 47r. ↵

- CRMI, f. 47v–48r. ↵

- CRMI, f. 42v; Dolens autem uxor reginaldi regis regina insularum tunc temporis super disiunctione sororis sue & olaui & mota felle amaritudinis totius quoque discordie seminatrix inter reginaldum & olauum, misit litteras latenter sub nomine reginaldi regis ad godredum filium suum ad insulam ski ut olauum comprehenderet & occideret. Godredus mox auditis litteris collegit exercitum, & reuera peruersam matris peracturum uoluntatem, si posset, uenit ad lodhus. ↵

- P. Stafford, “The Portrayal of Royal Women in England, Mid-Tenth to Mid-Twelfth Centuries,” in Medieval Queenship, ed. J. C. Parsons (New York: Springer, 1996), 143–67 at 146. The reference to Rognvald’s wife as regina Insularum, Queen of the Isles, is unique in the Manx chronicle and we know next to nothing about the Queens of the Isles. Ironically, perhaps, one of our final glimpses of the Manx dynasty comes in the person of Mary of Argyll, the daughter of Ewen son of Duncan, Lord of Argyll (d.c. 1268), who married Magnus Olafsson, the last Manx king, sometime before his death in 1265. She outlived her Manx husband and went on to marry no fewer than three further times. She died in 1302 and was regularly described as “queen of Man” long after Magnus’s death. Some basic information on her is collected at the People of Medieval Scotland Database: http://db.poms.ac.uk/record/person/7687; titles in Edward I and the Throne of Scotland 1290–1296: an Edition of the Record Sources for the Great Cause, ed. E. L. G. Stones & G. G. Simpson (2 vols. Oxford: OUP for the University of Glasgow, 1978), ii, 125 (“Mary, queen of Man and countess of Strathearn” from 1291), and 367 (“Domina Mar[ia] regina de Man,” appears, probably by mistake, among abbesses in a list of names in the Glasgow MS of those who swore fealty to Edward I in the summer of 1291). Further discussion in McDonald, Sea Kings, epilogue. ↵

- J. Beverley Smith, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd: Prince of Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1998), 37–41, quote at 39. ↵

- Johns, Gender, Nation, and Conquest in the High Middle Ages, 5. ↵

- CRMI, f. 40r. ↵

- CRMI, f. 40v. ↵

- Sixteenth-century Manx law allowed for the legitimization of a child born a year or two before the formalization of a marriage, although the application of later principles to an earlier period is something of which to be wary: The Statutes of the Isle of Man. Volume 1, ed. J. F. Gill (London, 1883; repr. 1992), 55, 68. ↵

- CRMI, f. 40r, 40v. ↵

- B. Ó’Cuív, “A Poem in Praise of Raghnall, King of Man,” Éigse 8 (1956–57), 283–301, at 289, 293; see also The Triumph Tree: Scotland’s Earliest Poetry AD 550–1350, ed. and trans. T. O. Clancy (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1998), 236–41. See now C. Etchingham, J. V. Sigurðsson, M. Ní Mhaonaigh, and E. A. Rowe, Norse-Gaelic Contacts in a Viking World: Studies in the Literature and History of Norway, Iceland, Ireland, and the Isle of Man (Brepols, 2019), ch. 3; Etchingham et al, 147, place the poem closer to the middle of the reign, perhaps ca. 1209–1212. ↵

- Ó’Cuív, 299 n. 8, cannot identify her, but states, “The name suggests that she was of Gaelic stock.” That the name may have held mythological and literary resonances is suggested in Etchingham et al, Norse-Gaelic Contacts, 188–90. ↵

- Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland Preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office, London, 5 vols: vols 1–4 ed. J. Bain (Edinburgh, 1881–88), vol. 5, ed. J. D. Galbraith and G. G. Simpson (Edinburgh, 1986), v, no. 9, p. 136. ↵

- B. Megaw, “Norseman and Native in the Kingdom of the Isles: a Re-assessment of the Manx Evidence,” in Man and Environment in the Isle of Man, 2 vols., ed. P. Davey (Oxford: BAR Publishing, 1978), ii, 278, states emphatically that Rognvald was not the son of Godred and Finnguala. ↵

- B. Jaski, Early Irish Kingship and Succession (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2000), 153. ↵

- Stafford, “Portrayal of royal women,” 146. ↵