8 The Physical and Environmental Boundaries of “Townlife” in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh

Graeme Morton

Elizabeth Ewan introduced the academy to the concept of “townlife” in her first single-authored monograph, Townlife in Fourteenth-Century Scotland.[1] Sourced from a mix of archaeological and archival research, Ewan pieced together the structures that underpinned the social history of the nation’s burghs, sketching out the managed environment within which ordinary people transitioned into townspeople. By juxtaposing “town” and “life,” she drew attention to the construction, governance, and maintenance of community life revealed within, and marked by, the administrative boundaries of the burgh. This research into the administrative spread of the town, and on managing its growing complexity, was built on the work of Michael Lynch and those who have highlighted the importance of institutional longevity in the transition from the medieval to the early modern burgh.[2]

It was increasingly characteristic of late medieval European towns that administrative and governmental structures enforced and limited by proscribed legal reach marked an economic place distinct from the countryside, although habitually linked through contract and debt.[3] Boundary making created a degree of local independence along with the imposition of obligations to act within the conventions and norms of what was to become urban life.[4] It is axiomatic that town life remained socially weakened and demographically fragile without governmental and administrative intervention, yet the urban experience, and the experience of being an urban person, was neither straightforward nor uniform. It is here that Ewan’s conceptual insight into the managed urban environment helps us explore the balance between local government and an emergent civil society. This urban community was the product of a managed infrastructure within an evolving set of administrative boundaries, whether those borders were marked by wattle fences, ditches, or gullies. The interconnection between burgesses and urban government was defined territorially, yet the relationship with the surrounding countryside remained fluid. Pastoral land as well as waste land was used by the townspeople for their animals, and many burgesses owned arable land, often divided into rigs, close to the town.[5] It was far from unusual to find townspeople who were also agricultural workers, and the town would inevitably suffer at times of poor harvest, such was the level of interdependence between the two. Townlife was not sealed by its boundaries and remained beholden to its natural environment and the unhealthiness of a cold and damp climate. Yet the late medieval and early modern community encapsulated therein was the product of administrative processes that involved negotiation and compromise within itself and at its margins.

This process of intervention, negotiation, and compromise, in shape and intent, continued during the decades when Scotland’s towns and cities experienced exceptional population and territorial growth, with all the concomitant pressures that transformation brought to bear upon their infrastructure and public health. By transporting Ewan’s conceptual innovation forward in time, this chapter examines local governance and management of the physical and natural environment of Edinburgh at the point when townlife transitioned into citylife. It was a period when the independence of local government grew against a background of administrative centralization in London, and the independence of action maintained by those who governed Edinburgh—a capital city in a stateless nation—reveals local government and associational activity to be key drivers in the creation of modern urban life and to the mitigation of a developing environmental challenge.[6]

Physical and Political Environment

In the decade that preceded Victoria’s ascension to the throne in 1837, the civic leaders of her Scottish capital sought legislation to create the administrative, policing, and infrastructural resources to govern a place widely proclaimed as the Athens of the North. Reflecting the operational difficulty of bringing Ferguson’s concept of civil society into a new age of urban complexity, this decade included the city’s bankruptcy and fundamental reform to its political representation.[7] With the burgh’s territorial size having changed little from the late medieval period through to 1814,[8] over the next century there were eight Extension Acts that spread the city from 598 acres to 10,877 acres by 1901. In 1920, when the city re-acquired the burgh of Leith—separate since 1833—along with the Midlothian parishes of Inveresk, Colinton, Longstone, Corstorphine, Cramond, Gilmerton, and Liberton, it meant another 23,000 acres were added.[9] In terms of governance, the fifteen layers of administration and ten layers of taxation built up between the burghs of Edinburgh and Leith were amalgamated into three administrative authorities and two rating authorities across one rating area.[10]

During the 1820s, the fourth and final phase of the New Town development was completed to ensure—for that part of the city at least—social order was manifest in the quartz sandstone that formed the frontages and gables of tenements that rose skywards from fine streets, crescents, and circles. Even when deprived of a proposed layout that followed the lines of the Union Flag, exactitude, coherence, and a regimented aesthetic emerged to bring a philosophy of rationality into physical form. The New Town’s architect James Craig was the nephew of James Thomson, poet and lyricist to the patriotic ode Rule Britannia (1740), whose jingoistic words adorned Craig’s maps. The naming of the new development’s streets honoured the Hanoverian family who held the united kingdom in their name, accentuating Edinburgh as Britain’s northern capital.[11] First began in 1767, the increasingly popular New Town would be connected to the medieval Old Town by the construction of George IV Bridge and by an earthen mound, the city magistrates’ growing ambition later laid out and funded through the Edinburgh Improvement Act of 1827. While not unique—and one can think of the metropolis of London in this regard—Edinburgh was and remains a city of connected villages, with the New Town being the most prestigious. The city’s population had swollen from around 57,000 in Webster’s estimate of 1755 to 111,235 in 1821, and then 136,294 in 1831 following the largest decadal growth of the century. By 1831, there were 10,607 houses valued at £10 or upwards in Edinburgh’s parliamentary returns, of which 9,383 returned inhabited house duty and the assessed taxes for the city stood at £68,547 8s 7d.[12] This income was enhanced by city customs exigible on cart loads of wheat, pease, beans, fruit, and other products, as well as animals and associated buildings that brought in around £4,337 per annum.[13] Yet this tax base swiftly required expansion—in the schedules of taxable income and in the extent of liability—for a burgeoning citylife to be administered and managed.

Table 8.1: Population of the city of Edinburgh, 1801–1901

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1801 | 67,288 |

| 1811 | 82,624 |

| 1821 | 111,235 |

| 1831 | 136,054 |

| 1841 | 138,182 |

| 1851 | 160,511 |

| 1861 | 168,121 |

| 1871 | 196,979 |

| 1881 | 228,357 |

| 1891 | 261,225 |

| 1901 | 298,113 |

Source: Rodger, Transformation of Edinburgh, 23

In contrast to the emerging suburbs, the city’s ancient royalty sat atop a narrow ridge of the volcanic plug leading up to the renowned medieval Castle that would morph close to its current silhouette with its Esplanade, first constructed in 1752–3, remodelled to better allow Scotland’s people to welcome George IV in 1822.[14] The Old Town had little room for expansion without its older properties being removed, and although linked by the North and South Bridges to the city’s expanding commercial and residential elite, in ease of access, if not in miles, the New Town remained a disconnected settlement. One contemporary bemoaned this isolation: “We have a large town on the north, and another on the south, which are so placed as if easy and mutual communication were of extremely little consequence to both.”[15] Managing the wynds, vennels, and closes of the Old Town was increasingly problematic as population densities increased. When the area experienced the great fire of 1824, it came with the enforced clearance of some of the city’s earliest tenements. This destruction resulted from a series of fires that originated in the premises of an engraver just off the High Street in Old Assembly Close—with at least 17 people reported injured and dead.[16] Clothing was collected and distributed in an act of charity for those who lost their belongings,[17] but it was increasingly clear that citylife had outgrown the boundaries of townlife.

The political administration of the city also went through a bonfire of its own, notably with parliamentary reform in 1832 and burgh reform in 1833. Around 166 free holders possessed the vote in 1831, and the city was a closed corporation that elected its own members.[18] Once Francis Jeffrey and Henry Cockburn had drawn up Scotland’s reformed electoral franchise to operate in tandem with the expanded franchise in England, around 10% of Edinburgh’s population gained the parliamentary vote and the proportionate change in the number of urban Scots entitled to choose their MP was significantly greater than in England.[19] Prior to 1832, many of the estimated 3,500 parliamentary electors across Scotland’s towns decided to exercise their right to vote in more than one place, and Edinburgh was the only Scottish town that returned its own—rather than a shared—member to Parliament.[20] This link between place and political representation was modest, and Scotland’s capital had no great claim to democratic rectitude, but the relationship between urban government and the growing middle classes was reinforced with the new property-based franchise, although it came at a time when financial mismanagement was to the fore.[21] The city of Aberdeen was bankrupted in 1817 and Edinburgh endured the same dishonour in 1833, with the construction plans of 1827 causing significant debt. “An Inhabitant” had warned the city’s newspapers in 1825 that compulsory assessment for the regulation of the Police should only apply to “objects of necessity and obvious public utility; and the expense of ornamental improvements must be defrayed by private arrangements or voluntary assessments.” By leaving compulsory arrangements unquestioned, the writer condemned the city’s taxpayers for “forfeit[ing] every pretension to their reputed character of an enlightened and intelligent population.”[22] Yet in the ambition of the 1827 Improvement Act, “reputed character” drove those citizens whom Sir John Sinclair lauded for their “zeal and public spirit” in the matter.[23]

Operating alongside the town council, the police commission was empowered by the Burgh Police (Scotland) Act 1833 to administer the social and infrastructural needs to the city, including the provision and maintenance of lighting, paving, street widths, public access, and the cleanliness of the environment.[24] These two administrative bodies, increasingly but not entirely overlapping in membership, confirmed the link between property ownership on the one hand, and the administrative governance of the burgh and the goal of civic virtue on the other.[25] The council election that followed was found to be sober and unfettered, with none of the “riot and intemperance” that had been observed in recent English boroughs.[26] While the day was wet and stormy, the “free, open poll” that contrasted with the “old closed system” saw 1,530 out of around 3,500 electors within the royalty cast their votes for six councillors.[27] They elected eight merchants, five booksellers, three Writers to the Signet, three builders, two medical men, plus nine others who came from different trades or professions.[28]

The candidates chosen for office indicate that preference was given to property owners and investors to not only manage the city, but to envisioning its renewal. A study of trusts, endowments, and educational charities shows the extended city emerging from choices made on investment options and a willingness to borrow and spend.[29] There is a certain sagacity in property owners of the town trusting no-one but themselves to administer the city through the town council and the police commission. It was avowed that those with the greatest knowledge of the community should govern, and those with the greatest financial stake in the community should have the greatest say in who those governors were to be and what level of debt could be carried.[30] What is more, it was those individuals who also invested cultural, philanthropic, and religious capital in the city—through subscriptions, donations, home missionary, and organizational endeavour—that affirmed the link between legislative government and civil society.

Urban Society, Civil Society

The work of Lynch and Ewan charted the role of voluntary and civic institutions from the medieval to the early modern period, and the next and expanded phase of voluntary activity found in the modern age deepened this interlocking network within the boundaries of the municipality and further still—directly through their constitutions and obligations, and also indirectly through patronage and private participation—with the post-reform town council.[31] For the burgh to succeed as a community, any mix of governance and civic patriotism needed substance.[32] In addition to the great educational charities that invested in feu and sub feu duties to generate capital for the building industry—despite a temporary lull in activity during the banking crisis of the 1820s—smaller charities sought to enhance the life chances of people who were ostensibly left out from the city’s transformation.[33] While also acting as a metaphor for the journey from townlife to citylife, the bridges and earthen mound that linked the Old and New Towns were augmented by social bridges in the form of voluntary associations whose subscribers sought to mitigate divided communities. The contemporary term “social inclusion” is perhaps the best way to characterize the work of the charitable associations that brought the wealthiest parts of the city into contact with the poorest parts, and which channelled an emergent social gospel in multifarious attempts to “save” the destitute from illness and vice. The maxim that “the amount of effort in the cause of Christ is the measure of love to Christ” was the underlying principle of home missionary activity.[34] The House of Refuge for the Destitute located on the High Street in the heart of the Old Town enhanced its care by providing support for children with disabilities while offering employment training and moral guidance derived from scripture.[35] The Parochial Mission for the Employment of Scripture Readers in the Old Town was focused on helping the same people with spiritual and temporal instruction, and was a charity that leaned heavily on residents of the New Town for its subscriptions, including £1 from the Lord Advocate Charles Bailie, a resident of Randolph Crescent, and similar sums from anonymous “friends” resident in Saxe Cobourg Place, Great King Street, and Heriot Row.[36] The Association provided sabbath schools by engaging twenty teachers to instruct 250 pupils in the parish of St Giles within the ancient royalty.

Given the gravitation of the city’s wealth to its southern development, the Society for the Relief of the Destitute Sick—in existence since 1785—was another charity that drew upon the New Town for its subscriber base. There were 965 subscribers to the Society in 1853, with the majority proffering a few shillings, but some such as the Misses Abercrombie from 19 York Place gave three guineas, George Buchan and George Cadell donated £4, Sir Graham Montgomery, MP provided three guineas, and John Wedderburn of the Union Bank proffered £5.[37] In this example, the voluntary organization’s link to the town council was a direct one. A deed of authorization from the magistrates of the city was arranged in 1813—a Seal of Cause—which not only made the operation of the Society secure, but, as a Body Corporate, required any change in its rules, or alteration to its charitable purpose, to secure approval by two-thirds of the council.[38] The Society’s management committee divided the city up into twenty-four districts, each with its own “visitor” who attended their duties weekly “with no reward but the blessed one of trying to do good, from love and pity for the suffering.” Applications for help were made on a form submitted to the society’s hall, located at 150 High Street, with any claims to infirmity evaluated by a physician.[39]

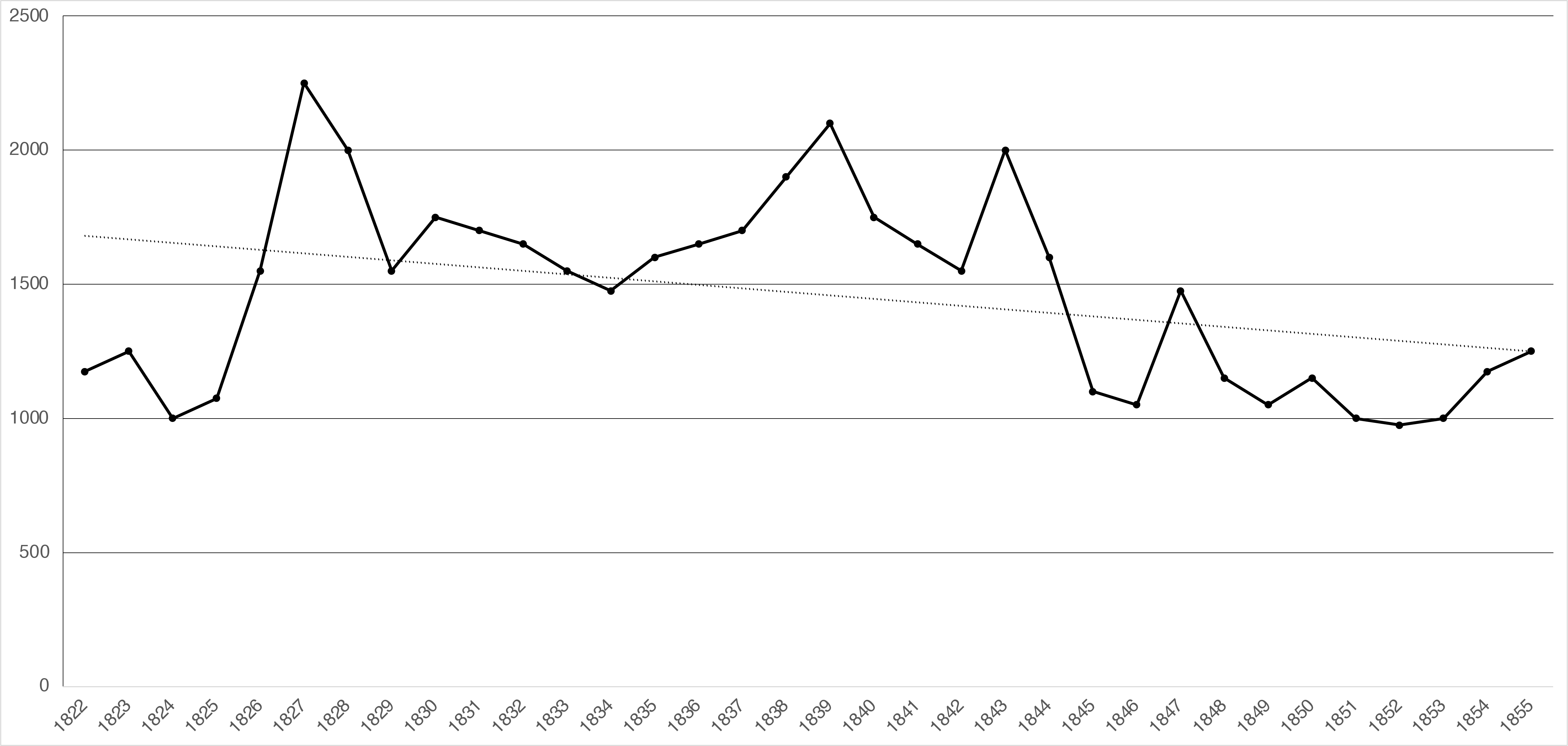

Figure 8.1: Financial Disbursement of the Destitute Sick Society, 1822–1855 (£)

Source: Seventieth Report of the Society for the Relief of the Destitute Sick, 11. Funds distributed during the 12 months prior to 15 November of the stated year.

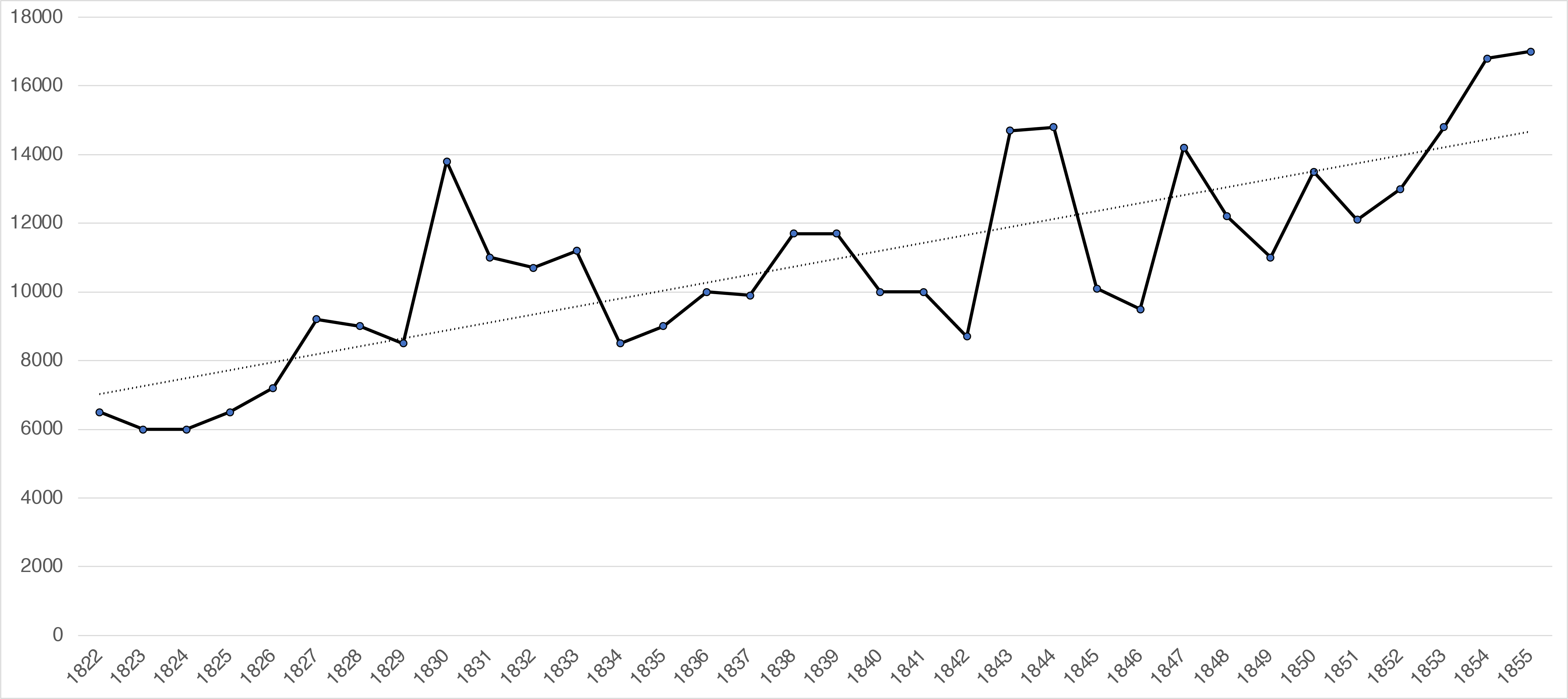

Figure 8.2: Number of Individuals visited by the Destitute Sick Society, 1822–1855

Source: Seventieth Report of the Society for the Relief of the Destitute Sick, 11. The number of people is counted for each repeat visit.

Over the period 1822 to 1855, a juncture that includes the introduction of the new Poor Law in 1845, the trendlines in figures 8.1 and 8.2 show the society’s financial disbursement diminished despite an increase in demand evidenced by a growing number of home visits. Taking that final year as an example shows £1,196 14s 10d was dispersed following 6,600 visits—with doles ranging from 4 or 5s per week to as much as 7s per week—plus there were 1,317 coal tickets and 5,405 meal tickets handed out, along with blankets, shoes, and clothing.[40]

Within annual reports replete with details from those given help in the face of social exclusion, the Destitute Sick Society assured its subscribers that “[v]ice has been assailed in its own dens with Christian weapons.”[41] When making an appeal for funds to build a “bridge between wealth and want,” Rev. Robert Wallace, of Trinity College Church, praised the society for bringing much needed cohesion to the city:

… we find that we have practically two cities before us—a city of poverty and a city of wealth—a city of enlightenment and moral eminence, and a city of ignorance and moral degradation. And just as commerce has found it needful, for the ends of traffic, at one place to span the separating ravine with a stately bridge, and at another to make it passible by a gigantic embankment, so the Christian philanthropist feels that there must be moral viaducts erected to bridge over the chasms that divide the different classes of Christian society, so that the knowledge of the enlightened may be channelled over to the ignorant, the piety of the good to the irreligious, and the sympathy and help of the affluent to the humble and the poor.[42]

While never of the scale to socially engineer a fundamental redistribution of wealth and want, philanthropic associational activity of this sort—defined in social purpose and geographic reach—was core to middle class identity, to urban management, and to advancing social justice within citylife.[43]

Boundary Expansion and Social Inclusion

A further aspect in the making of citylife, already suggested, was to expand the boundaries of the city to ensure those who lived within its environs were brought into its administrative, judicial, and taxable scope. The principle underlying the Royal Commission on Municipal Corporations of 1835 was for urban space to be manifest in “the important interests which the inhabitants of a town have in common,” ensuring that “arbitrary lines” were trumped by “interests occasioned by the contiguity and intermixture of small properties.”[44] Yet the Burgh Police acts of 1848 and 1850 had allowed any populous place over 1,200 persons in Scotland to become a distinct police burgh, and the Lindsay Act of 1862 reduced that minimum figure to 700. It meant that a simple vote could create a community with its own building and sanitary powers supported by a modest rate of taxation, allowing those communities to be separate and therefore exempt from the municipal rate.[45] Edinburgh and Glasgow both attempted to negate the “flight to the suburbs” that followed and regain those “free riders” who paid their own lower burgh rate, but still benefited from the city’s parks and public institutions.[46] Glasgow expanded its boundaries eleven times between 1830 and 1914, spreading tenfold in acreage to incorporate the burghs that had previously encircled the city.[47] Edinburgh expanded eight times between 1832 and 1901 (Table 8.2), enlarging its acreage by a factor of 2.5. The intention behind its extension in 1861, for instance, was to establish a process for administrative and sanitary oversight of the adjacent but still separate burgh of Leith, with legislation giving the council the right to buy land to reduce housing densities.[48] The city magistrates had previously known significant debts when incorporating neighbouring workhouses and asylums at times of boundary expansion and looked not to repeat the experience.[49]

Table 8.2: Edinburgh’s Expansion under Municipal Extensions Acts, 1832–1901

| Date of Municipal Extension Act | Approximate Area of Successive Additions (Acres) | Approximate Area of City (Acres) |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient Royalty (1685–1736) | N/A | 138 |

| Extended Royalty (1767–1814) | 460 | 598 |

| 1832 | 3,703 | 4,301 |

| 1856 | 263 | 4,564 |

| 1882 | 1,302 | 5,866 |

| 1885 | 95 | 5,961 |

| 1890 | 174 | 6,135 |

| 1896 | 2,468 | 8,603 |

| 1900 | 1,462 | 10,065 |

| 1901 | 812 | 10,877 |

Source: City of Edinburgh, 1920. Existing area of the city, showing the ancient royalty and areas of successive additions (London: HMSO, Ordnance Survey, 1920).

Concurrent with extending the tax base through boundary expansion was the conferment of rights and privileges and the enforcement of due obligations to ensure the newly annexed territory was fully part of the city administration. The magistrates took over all debts, including all bonds, assignments, leases, grants, conveyances, or other deeds or securities made under previous Acts, and confirmed that all contracts agreed under those Acts would remain valid.[50] The town councils of the neighbouring burghs being annexed as well as local landowners being impacted were to be compensated. The incorporation of the Braid Hills in 1890 required the area to be maintained by the town council as a public park and pleasure ground, where any games taking place were to be regulated. Both parties bound and obligated themselves to implement and perform their respective parts of the agreement under penalty of one hundred pounds sterling.[51] This administrative goal of matching the municipal and parliamentary boundaries, and the equal conferment of paving, lighting, gas, electricity, and policing obligations—building citylife through a process of negotiation and enforcement—required the aid and authority of Parliament to come into being. The procedure for each burgh extension saw a map of the boundaries being deposited with the town clerk. In the event of any dispute this map was granted precedence over the descriptions given in the legislation.[52]

The legislative landscape was iterative and not without complexities, which at times generated county and central government opposition and the perpetuation of social exclusion.[53] Where burgh incorporation had not taken place, cross-boundary Trusts were created to manage affairs and to provide political representation. Under the Water Act (1869), the undertakings of the Edinburgh Water Company were transferred and vested in the Edinburgh and District Water Trustees representing the city of Edinburgh, the burgh of Leith, and the burgh of Portobello for the management and administration of the supply for those communities and nearby districts. The bulk of the city’s water came from rainfall accumulating on the western slopes of the Pentland Hills, the springs lying between ten and sixteen miles distant.[54] The trustees under the Act were the lord provost of the city, the provosts of Leith and Portobello, seventeen representatives appointed from the corporation of Edinburgh, four from the corporation of Leith, and one from the corporation of Portobello. By 1920, such was the extent of these arrangements—and the rationale for the administrative streamlining then put in place—that 60% of Edinburgh’s capital debt, amounting to £6,127,425, lay with statutory Trusts and therefore was not directly controlled by the city.[55]

The conferment of harmonized rights, privileges and obligations through annexation, and the provision of equal access to, and ratable liability for, infrastructural and utility provision through statutory trusts, reinforced how social inclusion was beholden to the negotiation, management, and outcome of boundary expansion. In framing the horizontal community of citylife, this legislation augmented the property-based boundary of its political limits and the philanthropic reach of its civil society.

Nature, Density, and Overcrowding

Unlike its importance to the arrangement of statutory trusts and rating authorities, the legally defined boundaries of the city held little sway over climate and air quality. But managing and cultivating, and when necessary mitigating, the natural environment could not be neglected with impunity. Attempts to harness the natural world involved eschewing the commercial potential of undeveloped land for the health and cultural benefits that came from securing parkland for public use. The completed New Town gave up around one-tenth of its acreage to pleasure gardens, with half of those spaces being less than one acre in size, and the remainder evenly split between plots of one and three acres and over three acres. These private gardens were generally small and modest, with the houses orientated to the residents’ parks in front.[56] The public park, by contrast, was an attempt to improve the air quality of the city for those not able to afford the openness of the suburbs. In a lecture to the Saturday Half-Holiday Association meeting in Edinburgh in November 1856, Dr James Begg described public parks as the lungs of the city and essential to the future health and renewal of the working classes.[57] David Esdaile’s observations from his experience as a rural doctor also concluded that those born in “good air are much stronger and healthier” than those who are born into “crowded courts and back passages.”[58]

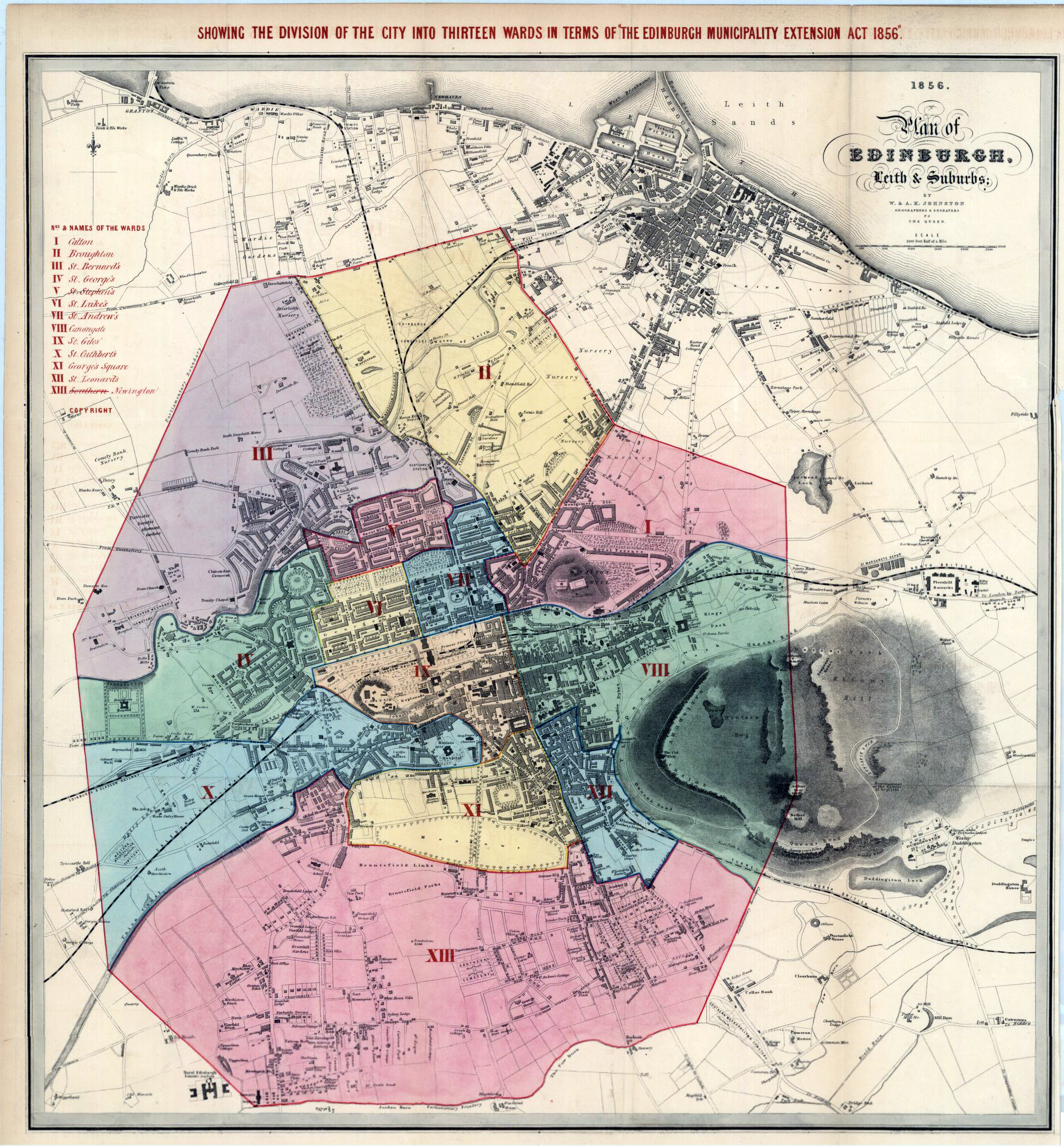

Nor had it gone unnoticed that the generous gardens and low-density housing of the New Town gave a false impression of the city’s moral and physical health. With a population of 170,444 in 1861 distributed across 4,191 acres, the city could boast that only 40 people were housed per acre. This compared well with Liverpool, which was home to 93 people per acre, and to Glasgow (83), Manchester (79), Dublin (66), and Birmingham (41). Yet Edinburgh’s spaciousness included the 243 acres of unpopulated land given over to Arthur’s Seat, masking significant variations between the 23.2 people per acre in the New Town and the 314.5 people per acre in the Tron area of the Old Town and the nearby areas of Grassmarket (237.6) and Canongate (206.7). The amount of unbuilt land surrounding the centre of the city, wards VIII, IX, XI and XII, and from Leith, is shown in stark relief in Figure 8.3. Even after these empty spaces started to be filled over the next decade, the death rate in the lower New Town (ward III) was 15.47 per thousand people, while the Tron (ward IX) was 34.55 per thousand people, fuelling contemporary concern over the relationship between housing density, poor air and light, and ill health.[59]

Figure 8.3: The Division of the city of Edinburgh into 13 Wards following the Edinburgh Municipal Extension Act (1856)

Source: Plan of Edinburgh, Leith & suburbs, showing the division of the city into thirteen wards in terms of the Edinburgh Municipality Extension Act, 1856. Edinburgh: William & A.K. Johnston, 1856. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Irrespective on the stage of the debate between miasmic and germ transmission theories of disease, overcrowding in the city had a disproportionately negative effect on life expectancy and mortality rates, notably amongst the very young. Of all deaths reported in 1858 in Scotland’s principal towns, 48% were children aged under five, amounting to 11,290 out of 23,420 people. In Leith the figure was 50% of the burgh’s deaths and in Edinburgh it was 41%. These rates had been steady over the previous three years and were considerably worse when only the poorest were counted.[60]

The creation of green space for leisure and the clearance of dilapidated tenements, cellars, and dens was part of the city’s response to these mortality rates, fuelled by the attention drawn by medico-climatologists to the effects of air pollution on health.[61] Dr Henry Littlejohn was appointed to the post of Medical Office of Health for the city in 1862, and while there was local opposition to the cost of his and similar offices elsewhere, across Scotland around £2m was borrowed by local authorities to remove poor quality housing.[62] Yet there was no immediate gain, and in 1868 it was possible to believe “there is no city in the empire where the inhabitants are more closely packed together in some districts, where there is a higher death rate, more disease, more abject poverty, more vice and wretchedness, than are sheltered in the miserable dens of the Old Town, which are seldom visited by the well-to-do inhabitants of our palatial abode.”[63] By the 1880s, an estimated £300,000 had been spent demolishing 30,000 insanitary homes in Edinburgh, with further demolitions taking place in Leith. Again, improvements were not immediately realized, a failing not helped when the President of the city’s trades council declared the town council had no responsibility for rehousing those people who were displaced. This was an argument driven by fear that intervention by the public purse would stymy the work of private builders, despite the town council being responsible for the public health and sanitary baseline of the city.[64] In 1885, Ballie Morrison raised with the town council the widespread concern that when demolition took place large numbers of people were never given the opportunity to access similar amounts of sanitary housing.[65] But there were limited signs of longer-term plans coming to fruition. Edinburgh’s City Improvement Trust, formed in 1867 to advance the layout, density, and sanitary health of the city’s streets, was enacted by parliament but operated separately from the town council in civil society. Its effectiveness can be measured in the reduction of the city’s death rate from 26.26 per thousand in the decade 1865–1875 down to 19.94 per thousand in the period 1875–1885.[66]

Yet averages, as we have seen, masked the levels of mortality recorded in the most unsanitary parts of the city, which were almost double those in the more salubrious west-end districts. Leith, empowered similarly, and in receipt of £100,000 borrowed for the purpose, had achieved little urban clearance by the middle of the 1880s.[67] This inability to harmonize density and mortality rates across the annexed burghs and combined rating areas of the expanded municipality was further challenged by changing climate trends and the arrival of influenza in the final decade of the century. Here citylife was exposed to a threat beholden to no boundaries, yet its mitigation was dependent on a reduction in social inequality.

Medico-Climatological Challenge

While the Edinburgh Municipal and Police (Amendment) Act of 1891 was a minor tweak on the Edinburgh Municipal and Police acts that had been passed since 1879, it created new controls to manage the risk of zoonosis and human infection.[68] The 1891 Act extended the magistrate’s power to inspect meat and order destruction of unsound food, and the power to enter byers to check cows and their milk. No wake would be held over the body of any person who had died of an infectious disease, and the occupier of the house where such a case was found, as well as anyone who knowingly attended, was liable to a fine of up to 40 shillings. The same penalty applied to parents of children who attended school after being in an infected house and for any teacher who knowingly allowed that child’s attendance in the classroom. The legislation was not without its failures, however. In 1897, it was thought that contaminated milk had been the cause either directly or indirectly of several breakouts of scarlet fever over the past two decades. Unhelpfully, the obligated warnings issued under the Notification Act suffered from the difficulty of differentiating scarlet fever from diphtheria, with the consequence that it was often acted upon too slowly.[69]

The challenge of keeping the people of Edinburgh safe in their consumption of food and milk was worsened where meat markets, dairies, and abattoirs were sited close to residential areas. In 1890, post-mortems carried out on a sample of 300 dairy cows in the city found 40% had bovine tuberculosis.[70] The mix of commercial, industrial, and residential activity in the poorer areas of the city, and the numbers of adults sleeping in rooms of limited cubic air capacity, evidenced the physical harm caused by a polluted atmosphere.[71] So, too, the environmental impact of cutting the quartz sandstone taken from Craigleith quarry to build the New Town, which took a heavy toll on the quarriers, stonemasons, and craftsmen involved. William Sankey, chartist and medical researcher, identified the danger of silico-tuberculosis from those workers inhaling dust imbued with quartz.[72] Along with the gestation of inorganic matters from cutting stone, “black lung” had also been observed amongst those working in the coal mines.[73] The economic activity of Glasgow and its environs was central to the UK’s industrial transformation, and that city’s levels of airborne carbon, the subject of Lord Kelvin’s research, revealed an atmosphere worse than—or at best equal to—that of London and Paris.[74] Edinburgh’s sobriquet of “auld reekie” came from the unceasing output of its domestic as well as its industrial chimneys, with the epidemiological impact from air pollution increasingly well known.[75] The Edinburgh-published Encyclopaedia Britannica did not include smoke as a subject until the fourth edition of 1810, then framed its entry around the negative consequences for health.[76] By 1891, the Royal Observatory on Calton Hill had become almost inoperable due to the “smoke-laden character of the air in that locality,” moving instead to the Blackford Hill at the city’s southern edge.

Scotland’s Astronomer Royal had taken over the onerous task of reducing into summary form the instrumental weather records compiled by the Scottish Meteorological Society (SMS).[77] The science of meteorology was deployed to explain variation in levels of mortality and morbidity across Scotland, across the burghs, and across the social classes.[78] In 1890, to take one example that illustrates the practical use made of these data, the town council of Edinburgh looked to its medical climatologists to help manage the influenza epidemic that was affecting all social classes within and across its boundaries. The epidemic had spread in the northern hemisphere contrary to the prevailing winds, spreading from east to west, and from north to south. Despite signs of influenza being present during October 1899, its arrival into Leith only came on 17 December with a crew from Riga. Other cases were confirmed throughout December in Aberdeen, Inverness, and Glasgow. Caithness and Sutherland were the areas worst hit with thirty deaths. Possibly only Glasgow reached the level of epidemic in January 1890, and levels of infection in Scotland were still relatively low compared to its prevalence in England.[79] Influenza was spreading in London amongst the children at Barnardo’s Home and had affected severely the operation of police constables and post office workers,[80] with both groups similarly impacted disproportionately in Cardiff.[81]

While the theatre and commercial districts of London were also badly hit, the Dundee Courier was at pains to doubt these cases were beyond the “normal levels of catarra attack”[82] and this sought to underplay the threat. As the first week of the New Year passed, the report from the Edinburgh Medical Officer of Health, tabled before the town council, listed no influenza patients being cared for. Bailie Russell, looking to reassure the council given cases had been identified in Leith, Aberdeen, and Dundee, assured his colleagues “we are quite prepared for them. We have a ward ready for them.”[83] Yet the town council almost immediately had cause for concern and the need for more hospital beds. On 14 January an estimated 14,000 cases were identified in Edinburgh and Leith, with the spread now classed an epidemic. By February, Pope Leo XIII—who in 1878 had restored the Catholic Hierarchy in Scotland—dispensed with Lenten fasting and abstinence given the threat posed by the disease to the earthly body.[84] By the third week of January, the Royal Asylum at Morningside had around 25% of its 990 staff and patients infected. The medical advice was to “study and observe the ordinary laws of health; breathe pure fresh air day and night, eat plain and simple, easily digested food; avoid mixtures; and in clothing study weather and temperature; keep mind and body usefully employed … ”[85]

Edinburgh’s medical climatologists had made use of research carried out on London to examine the association between climatic change and ill health in the city. Sir William Mitchell and Alexander Buchan reported their conclusions to the SMS. They had found a regular winter maximum in deaths due to influenza and a summer minimum for the years 1845–1890 that were associated with mean temperature.[86] While influenza was prevalent within the winter months, Mitchell established that it tended to take hold when those winter temperatures were exceptionally above average.[87]

Edinburgh’s average temperature for 1890 was more than one degree above the mean (for 1764–1896) and included a remarkably warm January average of 5.3°C against a norm of 2.7°C.[88] One who reflected on these data was Dr Alexander Lockhart Gillespie, appointed Medical Registrar for Edinburgh Infirmary in 1891. Working from the hypothesis that spikes in hospital admissions for bronchial and gut related diseases were linked to changes in the weather, Gillespie found that influenza had a distinct impact on admissions and its incidence developed irrespective of residential location. Seven years of data, amounting to 27,569 admissions to the Royal Infirmary, were logged, averaging 3,938 people per year. By examining extreme changes in temperature, rather than the mean, he investigated which climatic factors had the greater influence.[89] These were not patients with chronic conditions but instead had been admitted for acute or sub-acute reasons associated with influenza.

The epidemic of January 1890 lasted nine weeks before further incidences occurred in October 1891 and October 1893, with less destructive periods of spread in between. Gillespie’s control group of patients came from the staff at the Edinburgh post office who, as was the case in London and Cardiff, had experienced disproportionately the virulent outbreak. Post office employees were amongst the first body of workers to become ill, and were a group required to constantly criss-cross the wards of the city to make their deliveries. And while they were of a similar social class, it was established that these workers did not reside in close proximity to one another.[90] In contrast, though, Glasgow’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr James B. Russell, identified the city’s police and post office workers as experiencing only modest cases of influenza, whereas the growth of illness was greatest amongst those who were comparatively better off.[91] Yet in both cases, the climatic influence on the spread of the disease overwhelmed the internal and external boundaries of the city.

In this example, contemporaries had found that extreme and unseasonal temperatures exacerbated the effects of epidemic disease and undermined how effectively the health of the city could be managed. In extending the boundaries of the city, rights, obligations, and taxation were matched, and voluntary organizations worked with Christian zeal to bridge the gap between wealth and want. Yet still it was left beholden to town councillors and voluntary associations to tackle as best they could the prevalence of climate-induced zymotic diseases that spread across the urban environment.

Conclusion

Weather patterns may be localized but are wont to pay little attention to the administrative boundaries of a city. Townlife, and then citylife, was shaped by the success or otherwise of urban managers who raised taxation within those boundaries, and through local acts and trusts that managed the health and well-being of those who lived there. Whether in the fourteenth century or the nineteenth century, the structures of local and central government left space for guilds and philanthropic voluntary organizations to endeavour to mitigate inequalities in health and want. Improvement in sanitary conditions was uneven rather than lineal. Of the city’s 7,106 one-room houses surveyed in 1913, only 6.26% had a separate water closet with the remainder sharing facilities. Over half (57%) had a separate sink. Of those with two rooms—the largest category of housing at 23,466—64.3% had a separate water closet and 93.8% had a separate sink. Sculleries, though, were not common features. Only 0.2% of one-roomed houses, 4.2% of two-room; 18.7% of three-room, and 23% of four-room houses had this facility and therefore the means to separate household cleaning from food preparation. Where there was no scullery, the sink was generally found in the kitchen or on a shared landing or stair. Ashpits were no longer commonly used, and bleaching greens and public washhouses were provided, but heating remained a major cause of air pollution.[92] From the late medieval hearth, located in the centre of the room to provide both heat and a means of cooking, with peat most commonly used as fuel,[93] to the open range of the 1880s miner’s cottage, fuelled by slag and discounted or free coal, smoke was emitted and enveloped the city.[94] In 1857, Lord Campbell, who had first represented the Edinburgh constituency in 1834, told the Commons of the “heavy clouds of smoke” under which the classical cityscape was “overwhelmed and obscured.”[95] The subsequent Smoke Nuisance (Scotland) Abatement Act (1858) required all furnaces, whether locomotive or supplying a mill, factory bakehouse or public bath, or washhouse, to consume their own smoke. Yet “auld reekie” would continue to pollute the lungs of its residents, and after air monitoring was first introduced in 1914, with more robust data available for the 1930s, there is found a pattern of heavy concentrations of smoke around mealtimes at the start of the day and in the evening.[96]

It is the assessment of R. J. Morris that “Edinburgh was and is one of the most distinctive capital cities in Europe,” not least because it “was both a medieval and a modern city.”[97] Its medieval guild structure, the centrality of its feudal property law, and the nature of its trade within the British archipelago were part of this, but so too was the role of the guilds and their philanthropic successors—in the form of voluntary organizations and subscriber democracies—to manage the inequalities of its economy and society, and provide the means for its burgh community to be sustained. As Scotland’s capital city—in a nation without its own state—the people of Edinburgh learned to rely on voluntary organizations to help govern their citylife. The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland provided an important outlet for national debate, but the town council and the police commissioners were where local power was centralized.

Attempts to mitigate the increasingly recognized medico-climatic challenge to citylife radiated out from the capital through the work of scientists and amateur enthusiasts associated with the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Scottish Meteorological Society, although both bodies were hamstrung by their exclusion from the Treasury funding provided to the Royal Society and the Meteorological Department, then Office, in London.[98] From the fifteenth century to the first half of the twentieth century, Scotland’s climate warmed by 0.4°C,[99] with most of that rise coming in the 1930s after citylife had matured, thus mirroring the climatic consequences of urbanization and industrialization across the northern hemisphere.[100] The historical research presented here suggests that if today’s climatic challenge posed by and to citylife is to be arrested, and climate-caused poverty and ill-health be “assailed in its own dens,” as were its social and economic causes, then intervention, negotiation, and compromise at the boundaries of local government and civil society must be deepened.

- Elizabeth Ewan, Townlife in Fourteenth-Century Scotland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990). ↵

- J. R. D. Falconer, “Surveying Scotland’s Urban Past: The Pre-Modern Burgh,” History Compass 9, no. 1 (2011): 34–5; Michael Lynch, “Whatever Happened to the Medieval Burgh? Some Guidelines for Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Historians,” Scottish Economic and Social History 4 (1984): 5–20; Patricia Dennison, The Evolution of Scotland’s Towns: Creation, Growth, and Fragmentation (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), 110–37. ↵

- Chris Wickham, “How did the Feudal Economy Work? The Economic Logic of Medieval Societies,” Past & Present 251, no. 1 (2021): 24, 26–32. ↵

- Ewan, Townlife, 41, 137–9. ↵

- Ewan, Townlife, 14, 108–09, 157–8. ↵

- R. J. Morris, “Scotland 1830–1914: A Nation Within a Nation,” in People and Society in Scotland, vol. II: 1830–1914, eds. W. Hamish Fraser and R. J. Morris (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1990), 1–7; Joseph Curren, “Civil Society in the Status Capital: Charity and Authority in Dublin and Edinburgh, c.1815–c.1845,” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2017); Ciarán Wallace, “Civil Society in Search of a State: Dublin, 1898–1922,” Urban History 45, no. 3 (2018): 426–52; David McCrone, Who Runs Edinburgh? (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022), 24–32. ↵

- Adam Ferguson, An Essay on the History of Civil Society, 2nd edn. (London: Millar and Caddell, 1768), 338–52. ↵

- Richard Rodger, The Transformation of Edinburgh: Land, Property, and Trust in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 14. ↵

- Edinburgh Public Library, qYJS 4234.920, C22819. Edinburgh Boundaries Extension and Tramways Bill, 1920. Plans and Photographs; Edinburgh Boundaries Extension and Tramways Act (1920), 10 & 11 Geo 5, c. LXXXVII. ↵

- Edinburgh Boundaries Extension and Tramways Bill. Brief for Counsel for the Promotors. The Corporation of the City of Edinburgh. Edinburgh Corporation. Session 1920, 3–8. ↵

- M. K. Meade, “Plans of the New Town of Edinburgh,” Architectural History 14 (1971): 40, 44, 51. ↵

- Municipal Corporation: Burgh of Edinburgh. Report of Boundary Commissioners (1832), 9. ↵

- Duncan McLaren, Proposed Heads of Agreement to be Submitted to the Treasurer’s Committee of the Town Council of Edinburgh, by the Committee of Farmers and Traders, for a Commutation of all the City’s Customs (Edinburgh: T. Allan & Co., 1839), 24. ↵

- R. J. Morris, “Edinburgh Castle in the Modern Era: Presenting Meanings,” Edinburgh Castle Research Report (Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland, 2019), 1–2. ↵

- The Scotsman, July 25, 1827, 468. ↵

- The Scotsman, November 17, 1824, 819. ↵

- The Scotsman, November 20, 1824, 833. ↵

- House of Lords Deb. 13 August 1833, vol 20 cc563–76 “Burgh Reform Scotland”; Theodora Keith, “Municipal Election in the Royal Burghs of Scotland: II From the Union to the Passing of the Scottish Burgh Reform Bill in 1833,” The Scottish Historical Review 13, no. 15 (1916): 278. ↵

- Graeme Morton and R. J. Morris, “Civil Society, Governance and Nation: 1832–1914,” in The New Penguin History of Scotland: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day, eds. R. A. Houston & W. W. J. Knox (London: Penguin Books, 2001), 377–80. ↵

- Archibald Fletcher, “Memoir Concerning the Origin and Progress of the Reform, Proposed by the Internal Government of the Royal Burghs of Scotland,” The Edinburgh Review, January 1831, CIII, 210; John W. Gulland, How Edinburgh is Governed; A Handbook for Citizens (Edinburgh: T. C. and E. C Jack, 1891), 11. ↵

- Edinburgh’s pre-reform elections had been the subject of numerous challenges. See Edinburgh Public Library: Edinburgh Town Council – Election Cases, 1817–1821, vol. 1. ↵

- National Library of Scotland (NLS), 3.2844 (17): Papers Relative to the Edinburgh Compulsory Assessment Bill. Edinburgh, 1825: An Inhabitant, March 30, 1825, and April 1, 1825. ↵

- The Scotsman, March 21, 1827, 183. ↵

- Burgh Police (Scotland) Act 1833, 3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 46; Morton and Morris, “Civil Society, Governance and Nation,” 379. ↵

- David Barrie, “Police in Civil Society: Police, Enlightenment and Civic Virtue in Urban Scotland, c.1780–1833,” Urban History 37 no. 1 (2010): 45–65. ↵

- The Scotsman, November 9, 1833, 2. ↵

- The Scotsman, November 6, 1833, 3. ↵

- The Scotsman, November 6, 1833, 3. ↵

- Rogers, Transformation of Edinburgh, 4, 12. ↵

- Michael Dyer, Men of Property and Intelligence: The Scottish Electoral System Prior to 1884 (Aberdeen: Scottish Cultural Press, 1996). ↵

- Lynch, “Whatever Happened to the Medieval Burgh?”; Ewan, Townlife; R. J. Morris, “Urban Associations in England and Scotland, 1750–1914: The Formation of a Middle Class or the Formation of Civil Society?” in Civil Society, Associations and Urban Places, eds. G. Morton, B. de Vries, and R. J. Morris; Peter Clark, British Clubs and Societies, 1500–1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). ↵

- R. J. Morris, “Introduction: Civil Society, Associations and Urban Places: National and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Europe,” in Civil Society, Associations and Urban Places, 1–16. ↵

- Dyer, Men of Property, 6–7, 98. ↵

- History of Broughton Place United Presbyterian Church, with Sketches of its Missionary Operations (Edinburgh: William Oliphant and Co., 1872), 161. ↵

- House of Refuge for the Destitute, and Asylum for their Children, Morison's Close, 117 High Street, Edinburgh (Edinburgh: The House, 1832). ↵

- The Parochial Mission for the Employment of Scripture Readers in the Old Town, “List of Subscriptions” (Edinburgh: Neil and Co, 1858), 8–11. ↵

- Sixty-eighth Report ... Destitute Sick. ↵

- Seventy-second Report of the Society for the Relief of the Destitute Sick, Edinburgh, for the Year Ending 15th November 1857 (Edinburgh: Andrew Jack, 1857), 3–4; Seventy-Seventh Report of the Society for the Relief of the Destitute Sick, Edinburgh, for the Year Ending 15th November 1862 (Edinburgh: Ballantyne and Co, 1862), 4. ↵

- Seventy-second Report ... Destitute Sick, 5–6. ↵

- Seventieth Report of the Society for the Relief of the Destitute Sick, Edinburgh, for the Year Ending 15th November 1855 (Edinburgh: Andrew Jack 1855), 11. ↵

- Seventieth Report ... Destitute Sick, 5. ↵

- Seventy-Seventh Report ... Destitute Sick, 17–8. ↵

- Morris, “Urban Associations,” 141–2; Clark, British Clubs and Societies, 140. ↵

- Quoted in R. J. Morris, “New Spaces for Scotland, 1800 to 1900,” in A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1800 to 1900, eds. Trevor Griffiths and Graeme Morton (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), 228–9. ↵

- Morton and Morris, “Civil Society, Governance and Nation,” 379; Graeme Morton, “Civil Society, Municipal Government and the State: Enshrinement, Empowerment and Legitimacy, Scotland, 1800–1929,” Urban History 25, part 3 (Dec. 1998): 355. ↵

- Michael Pugh, “‘Centralisation has its draw backs as well as its advantages’: The Surrounding Burghs’ Resistance to Glasgow’s Municipal Expansion, c. 1869–1912,” Journal of Scottish Historical Studies 34, no. 1 (2014): 40–66; Morris, “New Spaces for Scotland,” 229. ↵

- Nicholas J. Morgan “Building the City,” in Glasgow Volume II 1830–1912, eds. W. Hamish Fraser and Irene Maver (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), 9. ↵

- General Police Act for Scotland. Report by Lord Provost to the Lord Provost's Committee, on Printed Letter of Provost of Leith, December 1860. 1861. ↵

- Edinburgh City Archives, SL146/9/1 “Register of the Edinburgh Charity Workhouse: July 1, 1835–June, 30, 1841.” ↵

- An Act to Amend and Consolidate the Acts Relating to the Municipality and Police and Roads and Streets of the City of Edinburgh; And for Other Purposes [21st July 1879]: 42 & 43 Vict., c. cxxxii. ↵

- An Act for Enabling the Purchase of the Braid Hills by the Lord Provost, Magistrates and Council of the City of Edinburgh to be Completed; For Extending the Municipal and Police Boundaries of the City, Including the Royal Burgh; For Prohibiting and Regulating Games on Bruntsfield Links; And for Other Purposes [2 May 1890]: 53 Vict., ch. iv. ↵

- Municipal Corporation: Burgh of Edinburgh. Report of Boundary Commissioners (1832), 910. ↵

- Michael Pugh, “Civic Borders and Imagined Communities: Continuity and Change in Scotland’s Municipal Boundaries, Jurisdictions and Structures—from 19th-Century ‘General Police’ to 21st-Century ‘Community Empowerment’,” Etudes Écossaises, 18 (2016): 29–49. ↵

- The Present Water Supply of Edinburgh, Leith and Portobello, with Suggestions for its More Perfect Distribution (Edinburgh: Colin Sinclair, 1870), 3–4. ↵

- Edinburgh Boundaries Extension and Tramways Bill. Brief for Counsel. ↵

- Connie Byrom, “The Pleasure Grounds of Edinburgh New Town,” Garden History 23, no. 1 (1995): 69. ↵

- Caledonian Mercury, November 17, 1856. ↵

- David Esdaile, Contributions to Natural History Chiefly in Relation to the Food of the People (Edinburgh: Wm Blackwood, 1865), 160. ↵

- Condition of the Poorer Classes, 12–3. ↵

- Fourth Detailed Annual Report of the Registrar-General of Births, Deaths, and Marriages in Scotland (Cd 3098, XIV.293 (1863): xxv– xli. ↵

- Appeal on Behalf of the Proposed Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh (Edinburgh, 1859), 34. ↵

- Anthony S. Wohl, Endangered Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain (London: J.M. Dent, 1983), 201. ↵

- Condition of the Poorer Classes, 12. ↵

- British Architect 23, no. 21 (May 22, 1884), 241. ↵

- The Scotsman, May 15, 1885, 6. ↵

- Second Report of Her Majesty’s Commissioners for Inquiry into the Housing of the Working Classes. Scotland (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1885), 6. ↵

- Second Report of Her Majesty’s Commissioners for Inquiry into the Housing of the Working Classes, 6. ↵

- An Act to Amend the Acts Relating to the Municipality and Police and Roads and Streets of the City and Royal Burgh of Edinburgh. [July 21, 1891]: 54 & 55 Vict. c. CXXXVI. ↵

- The Scotsman, November 17, 1897, 12. ↵

- Report of the Royal Commission appointed to Inquire into the Effects of Food Derived from Tuberculous Animals on Human Health (London: HMSO, 1898), 80-81. ↵

- John Tyndall, “Dust and Disease,” The British Medical Journal 24 June (1871): 661; T. Carnelley, J. S. Haldane, and A. M. Anderson, “The Carbonic Acid, Organic Matter, and Micro-organisms in the Air, more especially of Dwellings and Schools,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, 178 (1887): 66. ↵

- K. Donaldson, W. A. Wallace, C. Henry, A. Seaton, “Death in the New Town: Edinburgh’s Hidden Story of Stonemasons’ Silicosis,” Journal of the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh 47, no. 4 (2017): 377; W. V. Sankey, “Observations of the Masons’ or Stone-Cutters’ Disease,” The Medical Times, January 9, 1841, 177. ↵

- Tyndall, “Dust and Disease,” 661–2. ↵

- Karen L. Aplin, “Smoke Emissions from Industrial Western Scotland in 1859 Inferred from Lord Kelvin’s Atmospheric Electricity Measurements,” Atmospheric Environment 50 (2012): 373. ↵

- Duncan Lee et al. “Air Pollution and Health in Scotland: A Multicity Study,” Biostatistics 10, no. 3 (2009): 409–23; Matthew R. Heal et al., “Total and Water-Soluble Trace Metal Content of Urban Background PM10, PM2.5 and Black Smoke in Edinburgh, UK,” Atmospheric Environment 39 no. 8 (2005): 1417–1430; Andrea Sarzynski, “Bigger Is Not Always Better: A Comparative Analysis of Cities and their Air Pollution Impact,” Urban Studies 49 no. 14 (2012): 3121–3138. ↵

- John Douglas Billingsley, “The Perception of Air Pollution in Edinburgh” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 1973), 5.23. ↵

- Caledonian Mercury, July 30, 1858, 2. ↵

- Alexander Buchan and Arthur Mitchell, “The Influence of Weather on Mortality from Different Diseases and at Different Ages,” Journal of the Scottish Meteorological Society 4 (1875): 187–263. ↵

- Report on the Influenza Epidemic of 1889–90 by Dr Parson (London: HMSO, 1891), 11–2. ↵

- The Scotsman, January 2, 1890, 5; Daily Gazette, January 6, 1890, 3; The Scotsman, January 14, 1890, 7. ↵

- Aberdeen Journal, January 7, 1890, 5. ↵

- Dundee Courier, January 6, 1890, 3. ↵

- The Scotsman, January 8, 1890, 9. ↵

- The Scotsman, February 10, 1890, 9. ↵

- The Scotsman, January 21, 1890, 5. Original Emphasis. ↵

- Buchan and Mitchell, “Influence of Weather on Mortality,” 198–9. ↵

- The Scotsman, April 1, 1890, 3. ↵

- Robert C. Mossman, “The Meteorology of Edinburgh, Part II,” Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 39 (1897), 118. ↵

- A. Lockhart Gillespie, “The Weather, Influenza and Disease: From the Records of Edinburgh Royal Infirmary for Fifty Years,” Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 38 (1897), 579. ↵

- Gillespie, “The Weather, Influenza and Disease,”586–7. ↵

- The Scotsman, January 21, 1890, 5. ↵

- Report of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Industrial Population of Scotland, Cd. 8731, XIV.345 (1917–18), 77–8. ↵

- Ewan, Townlife, p. 22. ↵

- “Cooking on an Open Range” (c1880s), Newsquest, Licensor www.scran.ac.uk 000–000–121–038–R; “Coal Distribution,” Hansard, vol 385, 15 December 1942; “Miners (Coal Allowance),” Hansard, vol 415; “Miners” Concessionary Coal,” Tuesday Nov 6, 1945; Hansard, 484, February 12, 1951. ↵

- “Smoke Nuisance (Scotland) Abatement—Second Reading,” Hansard, 145: June 11, 1857. Public General Act, 20 & 21 Victoria I, c. 73; Act to Amend an Act of the Twentieth and Twenty-first Years of Her Majesty, for the Abatement of the Nuisance arising from the Smoke of Furnaces in Scotland, and an Act of the Twenty-fourth Year of Her Majesty, to Amend the Said Act. Public General Act, 28 & 29 Vict. I, c. 102; The Poor Law Magazine for Scotland, 8 (1866): 586. ↵

- Billingsley, “Air Pollution in Edinburgh,” 6.16–6.31. ↵

- R. J. Morris, “Philanthropy and Poor Relief in 19th Century Edinburgh,” Mélanges de l'école française de Rome Année 111 no. 1 (1999): 367–68. ↵

- Graeme Morton, Weather, Migration and the Scottish Diaspora: Leaving the Cold Country (London: Routledge, 2021), 28–65. ↵

- Morton, Weather, Migration and the Scottish Diaspora, 68; N. Ellis, Changes in the Scottish Climate: Meteorological Observations over the Last Century and Future Scenarios for Scotland. Information and Advisory Note No. 149 (Edinburgh: Scottish Natural Heritage, 2001). ↵

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, 2018: IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. ed V. Masson-Delmotte, et al. (Geneva: World Meteorological Organization), 21. ↵