Chapter 10 – Organizational constraints

“The basic building block of peace and security for all peoples is economic and social security, anchored in sustainable development. It is a key to all problems. Why? Because it allows us to address all the great issues-poverty, climate, environment and political stability-as parts of the whole.” (Ban Ki-moon)

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will accomplish the following learning objectives:

- critically review organizational linkages and constraints through the lens or responsible management

- understand relationships to sustainability and CSR in the organizational literature

In mid-May, the federal government announced a major program to help large companies address the economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. The Large Employer Emergency Financing Facility (LEEFF) will provide bridge loans to help companies address cash shortfalls due to the downturn. To access the program, companies must meet several requirements. One of them is to publish annual climate disclosure reports consistent with international standards, including how their future operations will contribute to achieving Canada’s climate goals.

Having companies report climate progress and risk exposure is smart. Climate-related financial disclosures are a reporting technique companies use to identify and disclose the material risks posed by climate change to their operations. This information helps companies to plan investments that mitigate the risks posed by climate impacts on their operations, supply chains, products and strategy. It also helps investors, lenders and insurers understand the risks a business faces.

Climate reporting is becoming increasingly common; 79 percent of Canada’s TSX-listed firms now provide some level of climate disclosures. Under the federal LEEFF program, firms’ reporting must follow the standards set by the Task Force for Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) – a widely accepted international best practice that has been endorsed and adopted by over 1,000 global companies and investors with a combined market cap of US$12 trillion.

Accessing LEEFF funding also requires companies to report on how their plans align with Canada’s international climate commitments – to achieve a 30 percent reduction by 2030, and net-zero emissions by 2050. This is smart policy. It supports emission reductions, and helps Canadian businesses prepare for where the global economy is going. Most firms are already moving in this direction by boosting energy efficiency, shifting to renewable power, adopting cleaner technologies, and developing plans to succeed in the global transition to a low-carbon economy, which offers a $26 trillion market opportunity across all sectors.

Some have taken issue with adding climate (and other) conditions to these federal loans, arguing that they should come with no strings attached. That is short-sighted. Responsible climate reporting and performance is increasingly becoming a requirement to secure investment, as evidenced by Blackrock, the Norwegian Pension Fund and many others who have recently announced they are divesting from high carbon businesses. To attract private capital, Canadian companies will need to meet the disclosure standards that most major investors are adopting.

Given that Canadian taxpayers are providing public money to support large businesses (as we should in this difficult time), it is smart and responsible to require those same world-class climate reporting standards. It is also entirely appropriate that those funds produce both private and public benefits – such as protecting workers’ pensions, promoting equity (by avoiding executive bonuses), and preparing for a low carbon future.

Responsible management may be executed as a holistic operation by individuals in organizations and is thus contingent on the particular ethical lens of the decision-making individuals within the context of their environment. Chandler (1) prescribes the use of CSR filters in the operationalization of organizational strategies into tactics. These filters are analogous to mediums that transmit the desired products to the end user – think of the sieves that allow fine grains but retain the husk. With that image in mind, consider what parameter constrains the use of those filters and how that then shapes the direction and actions of the organization.

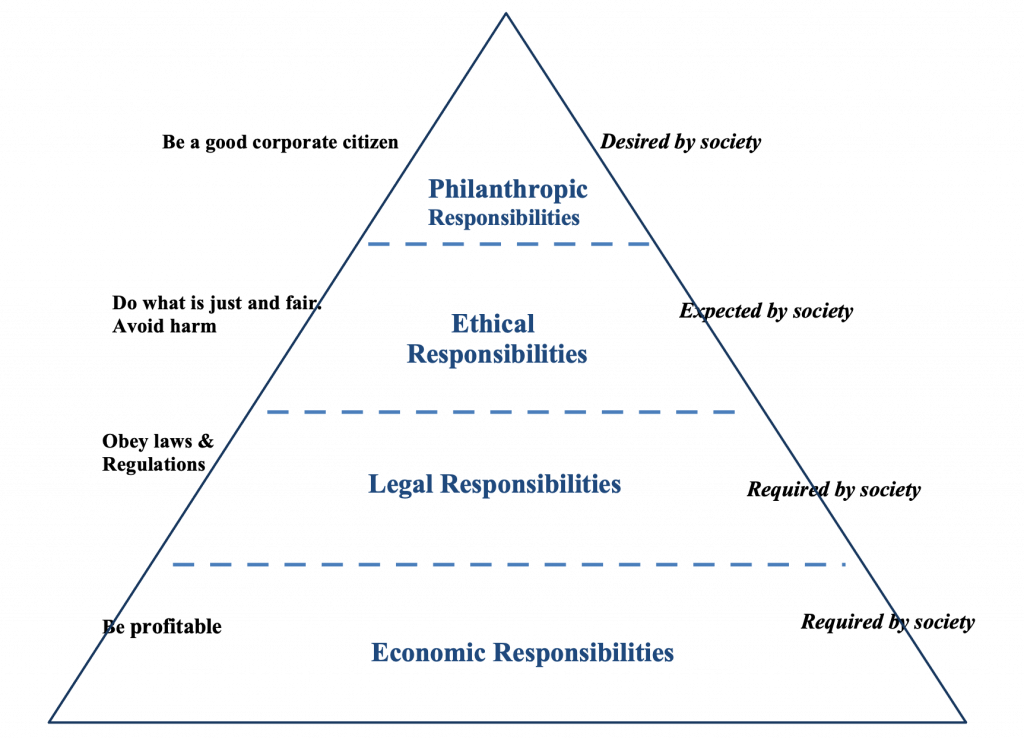

By reflecting on the pyramid of social responsibility (see Figure 1) and the discussions by Carroll (2) of the interactivity of its levels: one can consider the organizational constraints inherent in the levels of economic responsibilities, legal or regulatory responsibilities, ethical responsibilities and philanthropic responsibilities.

Economic constraints

Organizations function within a societal context where they need to operate with economic constraints. One way to look at the constraints on an organization is to take a resource based view (3). Barney (3) described a framework where unique resources form the basis for competitive advantage. Every firm or organization possesses competences or capabilities that they can do well but there are unique ones that can lead to a competitive advantage over others in the same space. Barney (4) provides a guide to identifying this core competence by using a VRIO framework where V defines the value of the competence, R defines its rarity, I defines its inimitability or uniqueness and O defines how this competence is organized or leveraged within the organization.

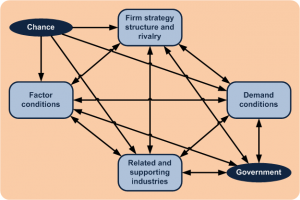

However, a contrasting view of economic constraints is proposed through the framework of industrial competition. Porter (5) considers four attributes at a national level in a ‘diamond’ framework to define the competitive advantages of nation (see Figure 2). There is an assumption of linkages and interactions between a firm’s strategy and structure at a local level, the nature of its demand (or local requirement) conditions, its attributes relating to ‘factors’ (availability of infrastructure and resources), and the impact of clustering or related industries. At an organizational level, Porter further explains the importance of a five forces model that considers the firm’s place within its industry as constrained by competitive rivalries, threats of potentital market entrants or substitute products/services, and the constraints resulting from power imbalances between suppliers and buyers.

The perspective of the stakeholder forms part of a holistic perspective as organizations exist within the constraints of society. Porter and Kramer (6) expanded on the concept of generating value that matters by a deeper consideration of stakeholders and what they value. In a complex and inter-related world, the concept of responsible management, then extends beyond considering resources exclusively or competitive industry pressures exclusively but rather integrates the perspective of what stakeholders value. The value proposition and its consideration become key to sustainability (7).

Responsible management links the economic survival of an organization to balancing the needs of society as described through sustainability efforts. Organizations need to incorporate responsible management through sustainability practices and CSR at the outset, through strategic planning and execution. This incorporation needs to be framed from an educational purpose at the outset of the academic journey (8) so that subsequent deep learning can form part of the behaviour of graduates as they engage with organizational careers (9). Ensuring that sustainability is part of this deep learning also requires intentional reinforcement of thinking along the ecological worldview, using a systems perspective, developing emotional and spiritual intelligence (10). Eventually responsible management depends on individuals making the ‘right’ decisions within the framework of achieving sustainability and CSR. The importance of individual actions can’t be minimized. Jaen, Reficco, and Berger (11) found that promoting inclusivity in a supply chain in the context of weak infrastructures such as the base of the economic pyramid requires a strong ethical foundation and behaviour by the organizational leader.

Legal or regulatory constraints

The legal and regulatory constraints are often governed by local governments and are highly context specific. Although, international guidance can be provided through supranational institutions like the UN and its 2030 Agenda of 17 SDGs or the ISO standards relating to CSR and sustainability (for example ISO-2600 is specifically oriented around implementing CSR within an organization), organizations isomorph towards conformance to local requirements. In Canada, the federal government provides guidelines for implementing CSR practices as suggested practices (https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/corporate-social-responsibility/en/implementation-guide-canadian-business); regulatory and standards bodies such as Standards Canada (https://www.scc.ca/) provide guidance from the mundane to the technical aspect of daily life. One of the standard bodies, the CSA Group provides information and guidance to all stakeholders regarding the linkages between the SDGs and the use of CSA standards (https://www.csagroup.org/sdg/).

Ethical constraints

Ethics and morals are linked. Stages of moral development influence the ethical orientation of individuals. Kohlberg’s stages of moral development were described by Baxter and Rarick (12) as important in the education of managers. Individuals go through six stages of moral development segmented into preconventional morality (where there is an orientation in the first two stages to obey rules and be transactional with obtaining rewards), conventional morality (where individuals over two stages are aware of social censures and approvals) and postconventional morality (where actions in these two stages are guided by more mature ethical principles that may lie along teleological or deontological dimensions).

Teleological ethics, as a consequential framework, focuses on the outcomes whereas deontological ethics, are focused on the process of universal rights and duties. From both of these views, as well as other views of ethics (such as virtue ethics, ethics of caring, ethics of justice and other frameworks), responsible management makes decisions that contingent on situational and personal circumstances result in outcomes that can impact sustainability and CSR. Jones (13), as discussed in an earlier chapter describes the ethical decision making process as one dependent on multiple factors but hinging on one’s perspective of ethics.

Constraints to purely philanthropic efforts

Rounding out the framework proposed by Carroll (2)(14), the philanthropic aspect of CSR depends on how responsible management views its applicability. As a purely non-transactional action, philanthropy can be highly individualistic. However, as part of responsible management it can be not only strategic in its implementation but also signal to external stakeholders a commitment to societally acceptable causes such as ecological and societal sustainability. Husted (15) provides a CSR governance model where philanthropy becomes embedded in an organization’s strategy by examining the centrality (how important is it to the core purpose of the organization) and specificity (how transactionally important is it to the organization) to classify relationships and networks to form partnerships through collaboration, focus on charitable giving or take a philanthropic project in-house.

This chapter described the constraints on an organization through the CSR framework provided by Carroll (2) composed of economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities by viewing those responsibilities as constraints on organizational action. This is just one of many possible ways of looking at the organizational constraints that must be considered by responsible management in their efforts towards sustainability and CSR.

Key Takeaways

Your key takeaways may be:

- that the pyramid of CSR framework provided by Carroll can be useful in describing organizational constraints;

- that responsible management needs to consider external and internal factors to achieve societal objective of sustainability.

If you are interested in exploring how business processes of SMEs can align with the SDGs, Verboven and Vanherck (2016) provide some prescriptive ideas to link tangible actions to the goals:

Reflective Questions

Take some time to reflect on how you would answer the following questions:

- Reflect on the “CSR pyramid” and identify the broader responsibility for an organization at each level of the pyramid. How does Carroll state that the pyramid levels are related to each other – are they interlinked, are they hierarchical, are they unique and different?

- Identify some of the key constraints placed on organizations (economic, regulatory, ethical, and philanthropic constraints) discussed in this chapter.

- How do the UN SDGs act as a regulatory constraint (or what is their relationship) at a national or organizational level?

References used in the text – you are encouraged to consult these references through your institutional library services or through the internet

(1) Chandler, D. (2020). Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Sustainable Value Creation (5th Edition). SAGE.

(2) Carroll, A. B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: The centerpiece of competing and complementary frameworks. Organizational Dynamics, 44(2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.02.002

(3) Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

(4) Barney, J. (1995). Looking inside for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Executive, 9(4), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.1995.9512032192

(5) Porter, M. E. (1990). The Competitive Advantage of Nations. (cover story). Harvard Business Review, 68(2), 73–93.

(6) Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and Society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard business review, 84(12), 78-92.

(7) Hart, S. L., & Milstein, M. B. (2003). Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Executive, 17(2), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.2003.10025194

(8) Sharma, S., & Hart, S. L. (2014). Beyond “Saddle Bag” Sustainability for Business Education. Organization and Environment, 27(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026614520713

(9) Burga, R., Leblanc, J., & Rezania, D. (2017). Analysing the effects of teaching approach on engagement, satisfaction and future time perspective among students in a course on CSR. International Journal of Management Education, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2017.02.003

(10) Hermes, J., & Rimanoczy, I. (2018). Deep learning for a sustainability mindset. International Journal of Management Education, 16(3), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2018.08.001

(11) Jaén, M. H., Reficco, E., & Berger, G. (2021). Does Integrity Matter in BOP Ventures? The Role of Responsible Leadership in Inclusive Supply Chains. Journal of Business Ethics, 173(3), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04518-0

(12) Baxter, G.D., & Rarick, C.A. (1987). Education for the moral development of managers: Kohlberg’s stages of moral development and integrative education. Journal of Business Ethics, 6, 243–248. https://doi-org.subzero.lib.uoguelph.ca/10.1007/BF00382871

(13) Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Organizations: An Issue-Contingent Model. Academy of Management Review. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1991.4278958

(14) Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G

(15) Husted, B. W. (2003). Governance choices for corporate social responsibility: To contribute, collaborate or internalize? Long Range Planning, 36(5), 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(03)00115-8