Chapter 4 – Individual Considerations

Now, the choice we face is not between saving our environment and saving our economy. The choice we face is between prosperity and decline. We can remain the world’s leading importer of oil, or we can become the world’s leading exporter of clean energy. We can allow climate change to wreak unnatural havoc across the landscape, or we can create jobs working to prevent its worst effects. We can hand over the jobs of the 21st century to our competitors, or we can confront what countries in Europe and Asia have already recognized as both a challenge and an opportunity: The nation that leads the world in creating new energy sources will be the nation that leads the 21st-century global economy. (Barack Obama, 2019)

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will accomplish the following learning objectives:

- You will understand individual considerations in the application of the principles of responsible management (RM)

- You will integrate the relationship between RM and leadership as an individual consideration for performance of CSR and sustainability

Example: The Alberta to British Columbia Transmountain Expansion Project

Source: https://cases.open.ubc.ca/the-alberta-to-british-columbia-trans-mountain-expansion-project/

This conservation resource was created by Lucia Park. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License.

Over the last decade, oil sands pipelines have been one of the most divisive issues in the political dynamics of energy in Canada. Oil sands are comprised of a mixture of sand, water, and bitumen (heavy oil which cannot flow on its own) (1). Due to their high viscosity and low mobility, oil sands are challenging to extract, transport, and refine. For these reasons, pipelines are considered to be the most convenient means of transporting crude oil and bitumen (2). At the centre of the discussions about oil sands pipelines is the Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Project. This project is proposed by an energy transportation and distribution company, Trans Mountain Pipelines.

On June 18, 2013, Kinder Morgan filed an application with the Canadian National Energy Board to triple the capacity of the pre-existing Trans Mountain pipeline to 1,150 km that transports oil from Alberta to British Columbia and Washington State (3). The Trans Mountain proposed to reactivate sections of the existing pipeline, enlarge storage terminals, and build new pump stations at the marine terminal in Burnaby (3). The federal government approved the Trans Mountain Expansion Pipeline on November 29, 2016 (3). However, the Federal Court of Appeal overturned the National Energy Board’s (NEB) approval of the Trans Mountain Expansion Pipeline in August 2018, citing insufficient consultation with First Nations groups and assessment of its environmental impact (4).

In June 2019, the Canadian government approved the Trans Mountain Expansion Pipeline for a second time (5). In July 2020, the Supreme Court of Canada dismissed the application from the Squamish Nation, Tsleil-Waututh Nation, and Coldwater Indian Band looking to challenge the federal government’s second approval of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion project. This decision by Canada’s top court ended the potential for any further legal challenges of the expansion project (6). In September 2020, despite challenges including the COVID-19 pandemic, a global slump in demand for fuel, and a $5.2-billion rise in its estimated cost to $12.6 billion, CEO Ian Anderson announced the project is advancing on schedule for completion by the end of 2022 (7). In March 2021, a study in British Columbia estimated that Canada will lose $11.9 billion because of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project (8). According to lead author and Simon Fraser University professor Thomas Gunton, the loss will be due to a “more than doubling of the Trans Mountain construction costs…combined with new climate policies that will reduced the demand for oil” (8).

INTERESTED STAKEHOLDERS AND RELATIVE POWER

The federal government of Canada is an interested stakeholder. They are a political decision-making body based in Ottawa, Ontario, outside of the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation community. The government of Canada has approved the Trans Mountain Expansion project because they believe it is in the Canadian public interest to provide thousands of middle-class jobs and increase access to global markets (9). Their objective is to generate $46 billion in government revenues over the first 20 years of operation (9). Through this project, the government of Canada hopes to become a stable global supplier of oil. Once the NEB releases its final report on the assessment of the project, the federal cabinet has the power to approve or reject the pipeline.

The Kinder Morgan company is a parent company of the Trans Mountain Expansion Project and it is an interested stakeholder. It is a Texas-based company and holds great importance to the economies of British Columbia and Canada (10). Its interests are in expanding the existing Trans Mountain Pipeline to access global markets and increase its revenues and profits. They have support from the federal government of Canada and pro-resource development advocacy groups. While not as powerful as the government of Canada, the Kinder Morgan company has significant power to influence major decisions.

Environmental organizations such as Raincoast Conservation Foundation is an interested stakeholder. It is based in British Columbia and is comprised of conservationists and scientists committed to protecting habitats and resources of umbrella species (11). Raincoast Conservation Foundation teamed up with other organizations to file a motion in the Federal Court of Appeal to appeal the pipeline expansion approval in November 2019 (11). These environmental organizations have been successful before at convincing the court to overturn cabinet approval of the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion project(11). These organizations are not as powerful as the government of Canada and the Kinder Morgan company when it comes to major decision-making power.

References

(1) Canadian Association of Petroleum Products (2019). Oil sands. Retrieved from https://www.capp.ca/canadian-oil-and-natural-gas/oil-sands

(2) Hart, A. (2013). A Review of Technologies for Transporting Heavy Crude Oil and Bitumen Via Pipelines. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-013-0086-6

(3) Trans Mountain (2019). Who We Are. Retrieved from https://www.transmountain.com/who-we-are

(4) Federal Court of Appeal (2018). Tsleil-Waututh Nation v. Canada. Retrieved from https://decisions.fca-caf.gc.ca/fca-caf/decisions/en/item/343511/index.do

(5) National Observer (2019). Canada Approves Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion For Second Time. Retrieved from https://www.nationalobserver.com/2019/06/18/news/canada-approves-trans-mountain-pipeline-expansion-second-time

(6) “Supreme Court dismisses First Nations’ challenge against Trans Mountain pipeline”.

(7) Trans Mountain pipeline expansion on schedule, on budget: CEO “Trans Mountain pipeline expansion on schedule, on budget: CEO.”

(8) “Evaluation of the Trans Mountain Expansion Project”.

(9) Government of Canada (2019). Economic Benefits of the Trans Mountain Expansion Project. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/campaign/trans-mountain/the-decision/backgrounder9.html

(10) Zmuda, K. (2015). Evaluation of the Regulatory Review Process for Pipeline Expansion in Canada: A Case Study of the Trans Mountain Expansion Project. Retrieved from http://rem-main.rem.sfu.ca/theses/ZmudaKatherine_2017_MRM675.pdf

(11) CBC (2019). Environmental Groups File New Challenge To Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Approval. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/trans-mountain-appeal-ecojustice-1.5204053

The previous chapter focused on the organizational form and the pressures and societal constraints that lead organizations to implement social responsibility (also known as CSR at the firm level) and more generally responsible management (RM). However, organizations are composed of individuals joining together for a common purpose. As the example in this chapter describes, the fact that Canada is a resource-rich country requires the negotiations and accomodations between different stakeholders to ensure a balance is struck among conflicting needs in the societal, environmental and economic dimensions.

In a for-profit firm, individuals join this organizational form towards capitalistic end results of making a profit within the ethical, rational, and economic constraints of what society imposes (1).

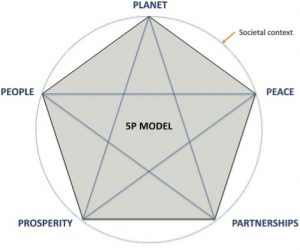

In a not-for-profit organization, individuals can choose aims that are aligned along multiple purposes, often-times in a way that aligns with the triple bottom line or the 5P model of sustainability (see Figure 1 that illustrates the 5P model) (2).

In governance-based organizations such as political groups or governments such as local councils, governing bodies, and other similar bodies, individuals can be elected or appointed to represent constituencies. The principles of responsible management here reflect the will of the society that the governing body represents in democratic institutions and the will of the governing body in more autocratic organizations. Our concern here is not with the political form but more with the implications for responsible management in the context of sustainability.

We can view individual considerations through the lens of several organizational theories which will be described with examples as to the individual contribution through these lenses to responsible management, to social responsibility, and to sustainability.

Agency theory is an important one to consider as responsible management by its very definition implies that the manager or leader is actually acting responsibly. The theory as initially proposed (3) was one that described the principal to agent relationship as a governance issue relating to conflict resolution between the two – owner to manager, employer to employee, etc. The important take-aways of agency theory are the resolution of information asymmetry between a principal and the agent, and the resolution of risks and uncertainties that result from this imperfect knowledge sharing (4). In the case for responsible management, agency theory is a factor that can determine the organizational behavior of a firm. For example Rimanoczy (5) studied the sustainability mindset of leaders and found an impact of mindfulness and reflective practices that translated into an organizational wide vision and mission. Providing a unified purpose and reducing uncertainty through the action of leaders can address some of the challenges identified through agency theory (3)

From a broader viewpoint, Freeman (6), reflected on the importance of identifying and considering all stakeholders as important to organizational strategy making. Stakeholders are identified as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of a corporation’s purpose” (7, pp. 6). Replace corporation by organization and you will have a more contextually accurate description of how stakeholder theory can be viewed in today’s environment.

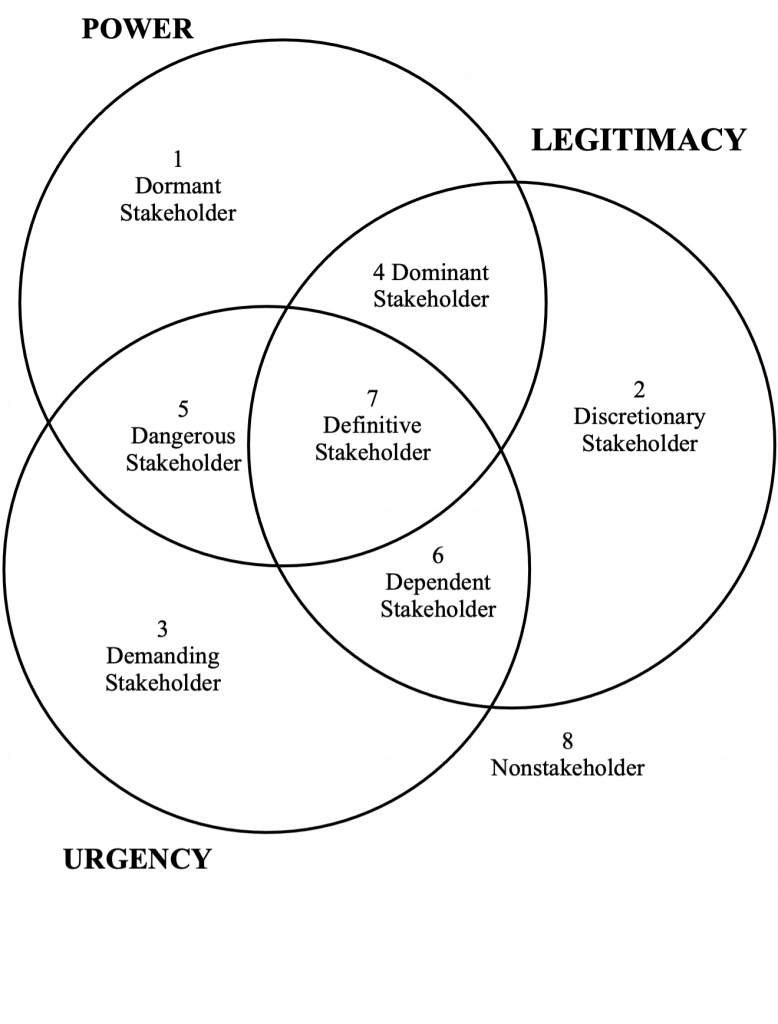

There is concern to ensure responsible management by managing for stakeholders (7). In that vein, it is important to identify who in fact are the stakeholders that should be prioritized as it is impossible to prioritize everyone. Mitchell and colleagues (8) described a conceptual model that prioritizes stakeholders according to their power, their legitimacy, and urgency as viewed by the management of organizations. This PUL model (shown in Figure 2) has been used in various project management settings and adjusted to account for additional vested interests (9). It is also used in considering the PUL from the viewpoint of sustainability (10)(11).

As responsible managers need to understand their organizational stakeholders, they also need to understand the relevance of contextual issues and how the organizations react to those issues. Zadek (12) provides an analysis that combines the salience of an issue with the organizational response by using real-life examples such as Nike, BP, Nordisk, and Rio Tinto. There are five stages that organizations exhibit systems-wide or specific to an issue (defensive, compliance, managerial, strategic, and civil) in the context of four stages of issue maturity (latent, emerging, consolidating, and institutionalized). Navigating through these issue-specific stages and how an organization reacts to their current issue illustrates the importance of stakeholder salience.

When there are institutions that promote responsible management such as the Principles for Responsible Management Education group of the United Nations, it is important to consider whether institutions would consider whether joining PRME is relevant or adds value to their organization? Majoch and colleagues (13) reviews the empirical evidence and concludes that in fact, there is value in organizations joining PRME and that institutionally, this type of stakeholder salience analysis provides benefits to the firms.

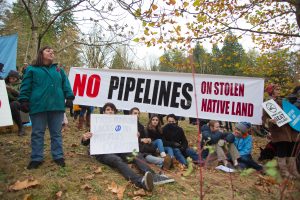

Leadership theories abound and have developed in line with societal developments. Perceptions of what makes a leader, what makes a follower and the relationship of the leader and followers with each other and within their organizations are important in relating to responsible management in the context of sustainability (14). For example, the question to be reflected on is whether leadership affects behavior or sustainability performance in organizations, does gender matter, what about indigenous leadership? (See Figure 3 for an illustration of current indigenous conflict between pipeline construction and native land sovereignty.) Go to the ‘take-aways’ section to explore some of the recent articles discussing these topics.

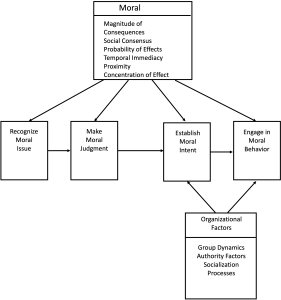

Ultimately, all individuals when faced with complex (or simple) problems follow a heuristic of decision making that can be derived from their ‘gut feeling’ (implicitly developed) or normative. Research theorists such as Jones (15) have proposed a model of decision making through the contextual lens of ethics, moderated by internal and external factors. Figure 4 describes the general steps towards ethical decision making. This model has been proposed and can be used in almost any situation. The complexity of decision making can increase when decisions are to be made as a group or need to be conveyed by a leadership team and may result in various stages of negotiations towards a consensus or a best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA as discussed in the negotiaton literature)(16).

Contemporary concerns with sustainability – particularly the existential dilemma faced in today’s anthropogenic age requires stakeholders to reflect deeply and make decisions that affect organizations, individuals, and political systems. This is where individual and organizational considerations overlap – as holistic considerations (often viewed through a systems theory lens) need to be viewed at multiple levels of analysis, at different times to arrive at decisions that are often just satisficing current problems rather than resulting in optimal solutions (17).

Responsible management is thus not just a leadership responsibility but cascades through all stakeholders involved in any issues (18). Results may be agreeable to many stakeholders but not provide evidence of an impact on sustainability which then results in other stakeholders actively reacting (see the example of stakeholder activism as a result of the laying of pipelines across Northern BC).

In the next chapter we will explore the linkages between organizational and individual considerations for responsible management in the context of sustainability.

Key Takeaways

Your key takeaways may be:

- that ethical decision making in the context of prioritization is not easy and is heavily context dependent;

- that responsible management should also be linked appropriate leadership behaviors that depend on the situation that an organization finds itself in.

Although agency and stakeholder theories are important as organizational theories, there are other theories that explain CSR as described by Frynas and Yamahaki (2016) in their roadmap article:

Reflective Questions

Take some time to reflect on how you would answer the following questions:

- What are the considerations that for-profit firms must take into account other than profit considerations (social and environmental sustainability and acting within the ethical, rational, and economic constraints of what society imposes)?

- Think of some constraints that society imposes on for-profit forms

- How do shareholders’ interest become aligned with company business principles and practices (management/executives/agency)

- Why is it in the interest of a corporation to create value for all stakeholders rather than just shareholders

- Revisit the 17 SDGs – How do the 17 SDGs developed by the UN reflect the 5Ps (re-word). What goals reflect what P(s). How are the 5Ps reflected across the 17 SDGs

References used in the text – you are encouraged to consult these references through your institutional library services or through the internet

(1) Chandler, D. (2020). Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Sustainable Value Creation (5th Edition). SAGE.

(2) Lawrence, R. J. (2020). Overcoming Barriers to Implementing Sustainable Development Goals. Human Ecology Review, 26(1), 95-116.

(3) Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of financial economics, 3(4), 305-360.

(4) Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/258191

(5) Rimanoczy, I. (2014). A matter of being: Developing sustainability-minded leaders. Journal of Management for Global Sustainability, 2(1), 95-122.

(6) Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management : a stakeholder approach. Pitman.

(7) Freeman, R. E., Wicks, A. C., & Harrison, J. S. (2007). Managing for Stakeholders : Survival, Reputation, and Success. Yale University Press.

(8) Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886. https://doi.org/10.2307/259247

(9) Olander, S. (2007) Stakeholder Impact Analysis in Construction Project Management. Construction Management and Economics, 25, 277-287.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01446190600879125

(10) Burga, R., & Rezania, D. (2016). Stakeholder theory in social entrepreneurship: a descriptive case study. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0049-8

(11) Kusyk, S. M., & Lozano, J. M. (2007). SME social performance: a four-cell typology of key drivers and barriers on social issues and their implications for stakeholder theory . Corporate Governance, 7(4), 502–515. http://dx.doi.org.library.sheridanc.on.ca/10.1108/14720700710820588

(12) Zadek. (2004). The path to corporate responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 82(12), 125–150.

(13) Majoch, A. A., Hoepner, A. G., & Hebb, T. (2017). Sources of stakeholder salience in the responsible investment movement: why do investors sign the principles for responsible investment?. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(4), 723-741.

(14) He, J., Morrison, A. M., & Zhang, H. (2021). Being sustainable: The three-way interactive effects of CSR, green human resource management, and responsible leadership on employee green behavior and task performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(3), 1043–1054. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2104

(15) Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Organizations: An Issue-Contingent Model. Academy of Management Review. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1991.4278958

(16) There are many current textbooks focused on negotiation that explain BATNA; our reference is Lewicki, R., J., Barry, B., & Saunders, D., M. (2007). Essentials of Negotiation (4th Ed.). McGraw-Hill Irwin.

(17) An excellent discussion of the challenges of applying a systems approach and embedding sustainability is discussed in Laszlo, C., & Zhexembayeva, N. (2011). Embedded Sustainability: The Next Big Competitive Advantage. Stanford Business Books.

(18) Responsible management is promoted through various institutions such as the PRME iniative from the UN SDGs. Dr. Laasch has written articles and a textbook focused on this topic. Read the following: Laasch, O., & Pinkse, J. (2020). Explaining the leopards’ spots: Responsibility-embedding in business model artefacts across spaces of institutional complexity. Long Range Planning 53, 101891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.101891; also read Laasch, O. (2021). Principles of Management: Practicing ethics, responsibility, sustainability. SAGE Publications Ltd.