Chapter 5 – Forming Linkages

Sustainability is the integration of environmental health, social equity, and economic vitality in order to create thriving, healthy, diverse and resilient communities for this generation and generations to come. (UCLA Sustainability Committee, 2016)

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will accomplish the following learning objectives:

- You will make the linkages between individuals and organizational performance of responsible management (RM)

- You will understand the importance of the base of the economic pyramid in global considerations for RM

- You will understand the linkages to equity, diversity and inclusivity as key components of RM

Example: The background of the emergence of Grameen Bank

Source: Rahman, R., & Nie, Q. (2011). The synthesis of Grameen bank microfinance approaches in Bangladesh. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 3(6), 207-218.

https://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ijef/article/view/12701

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The Grameen Bank started with the belief of an individual- a young economist visiting the famine driven rural communities of Bangladesh in 1974. Through a conversation encounter with a bamboo stool maker who was trapped in the vicious cycle of poverty, this young economist, by the name of Muhammed Yunus, discovered a dire condition and a dire need in Bangladesh (1). As the high-interest rates offered by moneylenders, many rural areas were cursed by poverty. With a strong faith in the poor- a faith that they would repay on time without the threat of confiscation or collateral, and faith that they would know how to maximize the benefits of their loans without any training – Yunus decided to take action, lending $27 of his own money to the villagers (1). As his $27 loan was fully repaid, Yunus was more influenced that the people who were poor were equally ready and capable to repay loan on their own ingenuity. This is also believed by him that he had found a workable process that might help the poorest of the poor earn though self-starting.

Yunus applied the Grameen Bank project in 1976 as pilot basis in Jobra village (a village adjoining to Chittagong University, Bangladesh) as a trial to judge his belief on a large scale. The research project was examining the possibility of designing a credit delivery system to provide banking services targeted at the rural poor. The bank primarily restricted its extent to the village of Jobra, but after two years of success, it extended to the district of Tangail. The successful Grameen Bank project officially became the Grameen Bank in 1983- a self-regulating, member owned bank for the poor. Today Grameen bank is owned by the rural poor whom it serves. Borrowers of the Bank own 95% of its shares, while the remaining 5% is owned by the government (2) (3).

While small loans to women have been the primary focus of Grameen Bank since its inception in the course of its development, it realized that new organizations are needed to be established to focus on the non-banking activities. The Grameen family of organizations was thus founded and currently eight different organizations are providing devoted activities in the following areas: venture capital, communications, Internet service provision, textiles, energy, education, and telecom.

References:

(1) Dowla. Asif and Dipal Barua. (2006). The Poor Always Pay Back: The Grameen 2 Story. Bloomfield: Kumarian Press Inc.

(2) Casuga M.S. (2002). Documentation of product development process in selected MFIs-review of literature. Microfinance council of the Philippines. Inc. Philippines.

(3) GB. (2010). Grammen Bank. banking for the poor. http://www.grameen-info.org/index.php?option=com_frontpage&Itemid=68.

Responsible management through corporate social responsibility initiatives or other sustainability initiatives happens because our society has embraced the organization of individuals into groups for profit-seeking actitivities (corporations), for social purposes (not-for-profit and NGOs), for political governance (governments) and for combinations of many of these purposes (social entrepreneurial enterprises are an example of firms that embrace profit-seeking motives but have a fundamental commitment to social contributions). And so it is that in the given example of the Grameen Bank, a shared value is created between stakeholders and the organizational business structure.

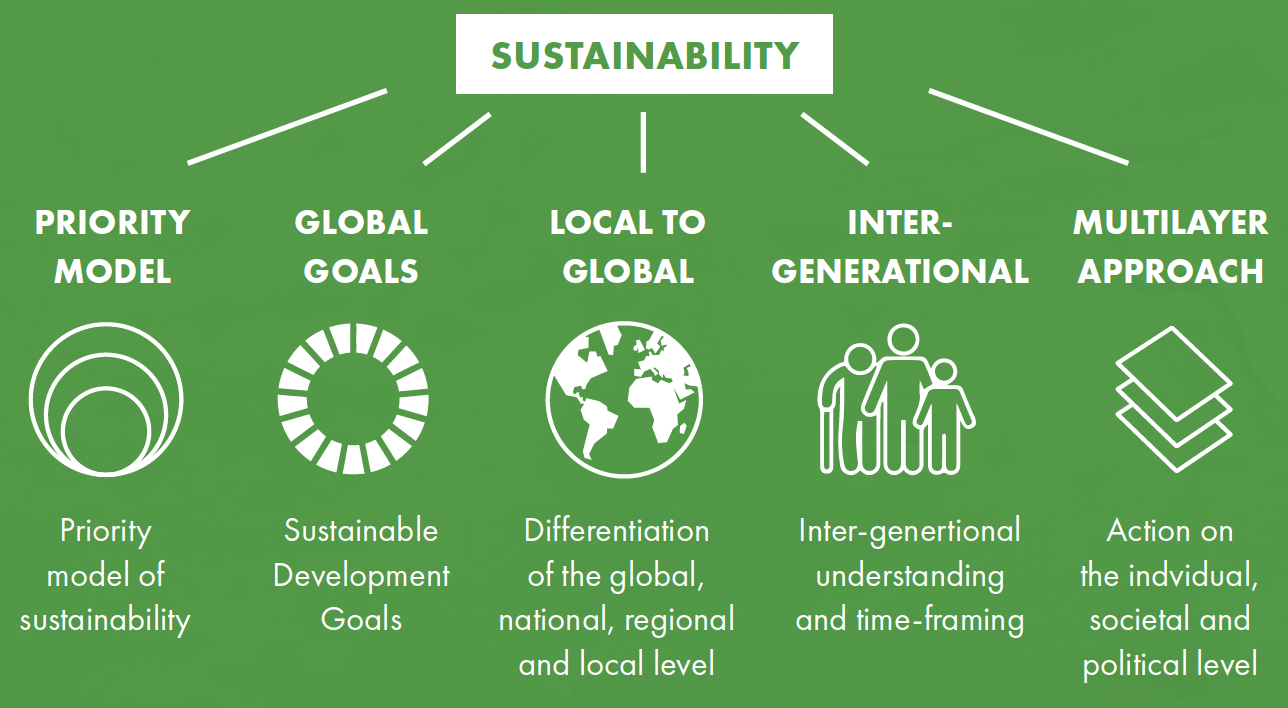

In previous chapters, we separated individual considerations, organizational considerations and discussions of theory. In this chapter, we provide linkages between these concepts based on current research in a Canadian context and premised on holistic lenses from broader societal goals articulated by organizations and agendas such as the UN Sustainable Development Agenda as promoted through the logo shown on Figure 1 (1), the Principles for Responsible Management initiatives (https://www.unprme.org/), and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues guiding corporate behaviour.

We adopt a social constructivist view of society which basically means that we, as participating members of society, construct our own reality and evolve it with changing societal conditions. This greater emphasis on stakeholder involvement for sustainability is described by Freudenreich and colleagues (2) as a need for businesses to consider the variety of stakeholder needs and changing values in the creation of value, not solely for the business but more specifically for enhancing stakeholder relationships.

Taking the Western view of management (sometimes referred to as a neo-colonizing viewpoint), groups of individuals gather into organizations to satisfy specific needs determined by the organizers of the group. In CSR literature and the responsible management (RM) literature, the focus is on corporations – that is businesses that operate according to certain regulatory principles and laws. These corporations are aligned behind a business vision (mostly articulated but sometimes implicit) that attempt to provide a guiding light with missions and strategies aligned to that vision. In most cases, the business’s objective is to deliver value of some sort to consuming stakeholders and through this transactional operation become economically sustainable.

Porter and Kramer (3) in a seminal paper, explored the determination of value and its relationship to the firm and focused on the importance of creating shared value that integrated social good with a business framework to enhance competitiveness. In later research, the concept of shared value with explicit linkages between social and business results was expanded on by reconceptualizing the definition of the organizational outputs (products and markets), redefining the supply chain, and expanding on the benefits of mutual accomodations from cluster configurations and developments (4). The focus on shared value then is the underlying motive behind strategic purpose that incorporates the elements of sustainability. An example of the multi-dimensional aspect of sustainability is illustrated through Figure 2.

To achieve responsible management within the firm, it is important to embed sustainability principles in the process of determining the firm’s strategy. This includes not only the transactional aspect of determining value for a firm’s consumers but also for the other stakeholders who have input or influence on the firm. An often-neglected stakeholder group who not only helps to determine the firm’s value but is also fundamental to its viability is composed of the individuals who make up the organization – employeers, managers, owners, directors.

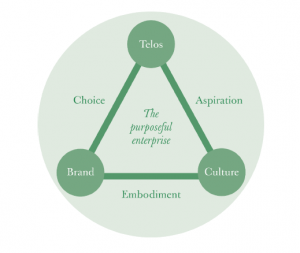

In their practical discussion of purposeful organizations, Houston and Pinches (5) have argued that the sustainability and success of firms are tied to the strength of the linkages between the purpose (defined through the greek word – telos) of the firm, its brand, and its culture all embodied through the commitment of the organizational members. Each one of the pillars are critically linked by transformational levers. This model is shown in Figure 3. The purpose/telos of the firm is embodied through the explicit and perceived branding that the firm portrays and is embedded through the lever of aspiration to its culture. Individuals feel more connected when their organizational purpose aligns with their own values. So the transformational lever of embodiment operationalizes or makes real that alignment between the culture of the organization and its brand. The leadership of the organization when appropriately contextually applied as servant, relational, or transformational leadership creates a condition where individuals can believe that their own individual purpose is aligned with that of their organization. So, in effect, the firm’s values can be shaped through its internal culture and sense of purpose (5).

One of the emergent concerns that impact social responsibility, particularly among nations that are existing beyond the subsistence level is the struggle to achieve equity, diversity and inclusivity (EDI) in all aspects of daily living. In Canada, a multicultural society, this concern extends beyond accessibility concerns for those individuals who are disadvantaged by services and products aimed at people who are unaffected by differently abled attributes such as blindness, deafness, inability to use one or more bodily function or limb and differently abled inviduals with unique mental or intellectual abilities. Changing demographics in Canada and the rest of the world does demand a rethink. For example, Golub and colleagues (6) found how intergenerational equity based on a reflection on historical drivers of injustices and forms a frame for “restorative justice” and ultimately support for sustainability from a societal viewpoint. These concerns are often addressed by regulatory and legislative requirements for accessibility in federal, provincial and privately-initiated services.

In addition, responsible management has to be concerned with a widening concern for elder care (as particularly salient in the high death rate resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada) and for considerations and care for communities of people who identify in a different way than the majority of the population (whether that is defined by labels such as LGBTQ2 or by racialized individuals or communities). The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom (7) in Canada and various human rights codes (for example the Ontario Human Rights code) specifically prohibit discriminations along multiple factors. In addition, supra-national initiatives such as the UN Sustainability Agenda have Sustainable Development Goals specifically aimed at reducing inequalities (SDG #10 ) and gender equality (SDG #5). (Each of the SDG logos are shown in Figures 4 and 5.) The application of EDI goes beyond just fulfilling legal and regulatory requirements but as Daya (8) explains from researching these issues in a South African context, organizational effectiveness improves when EDI becomes an inclusionary part of internal operations.

In the application of sustainability as visioned by the SDGs (SDG 5 on gender equality and SDG 10 on reducing inequalities), Adamson and colleagues (9) ask us to be critical about understanding the differences between terminology that is currently used such as ‘inclusion’ and ‘diversity’. They suggest that inclusion is linked to reducing barriers whereas the use of diversity implies the heterogeneous make up of an organization. However, aiming to achieve greater diversity and inclusion may also enhance organizational tensions when considering the different aspects of sustainability. Ashraf and colleagues (10) examined these tensions in the context of environmental projects such as reduction of waste and control of greenhouse gases to conclude that firms in effect, the organizations undergoing tension need to broker some type of accomodation between stakeholders groups to achieve a satisficing level that addresses different aspects of sustainability.

The gender aspect of sustainability is also important as Al-Shaer and Zaman (11) find that more gender diverse boards lead to greater quality sustainability reporting. Below the board level of management, however, Henry and colleagues (12) explains that top management diversity from the viewpoint of different functional skills leads to better performance in achieving triple bottom line goals. Gender diversity, in addition, influence leadership styles and subsequent integration of corporate social responsibility as Alonso-Almeida and colleagues (13) describe in their analysis of top managers in Spain.

Exploring the linkages between individuals and their organizations; the link to setting up values, and the preoccupation of achieving meaningful results against international sustainability standards can also be viewed from the perspective of the ‘base of the pyramid’ segment of the global population. This base of the pyramid discussion was popularized by Prahalad and Hart (14), Hart and Christensen (15) among others, and further elaborated in a book by Prahalad (16) discussing the opportunities that exist in the lower economic tiers of the global population. These opportunities are viewed as synergistic and mutually advantageous to firms trying to leverage their presence in an emerging market and for local firms to leverage their innovations into value that can be translated not only within their market but in other markets. An example can be viewed through various efforts by firms such as Unilever and the innovations they developed for emerging markets and by innovators in emerging markets leveraging existing technology to address local economic and social needs. An example of the latter can be seen through the Grameem Bank in Bangladesh, set up by Ashoka Fellow Mohammed Yunnus to provide micro-credit and lending opportunities for otherwise non-liquid borrowers who would not otherwise qualify for loans. This example has been copied and used in various parts of the world.

In this chapter, we expand our vision beyond the neo-colonial perspective that dominates transactional and global economics to an indigenous perspective. The indigenous perspective is described by the viewpoint of peoples who inhabited lands prior to the arrival of colonials – such as the Maori in New Zealand, the Aboriginal tribes in Australia (some interesting discussion is provided by Throsby and Peterskaya (17)), and various tribes and groups across Africa, most of North and South America (Merino and Gustaffson (18) discuss that indigenous movements in Peru are being recognized as environmental stewards). Scheyvesn and colleagues (19) looks at indigenous tourism practices in the context of indigenous people in Fiji, Australia, and New Zealand and how community engagement furthers the achievement of the SDGs. In the context of the Canadian experience in this book, the indigenous perspective is that of First Nations and Inuit people in Canada. This perspective has a holistic viewpoint expressed through covenants with each other, with the land, and across generations [refer to the seventh generation perspective described in the Truth and Reconciliation Committee reports]. Under this perspective the linkages between people and the land is mediated and given voice through a systemic execution of sustainability in their narratives, in their oral traditions, cultures and mores and in their traditional living (for an interesting narrative centered on this sustainability viewpoint read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer).

We appear to have come full circle with an initial chapter discussing the viewpoints of individuals, those of organizations, and by exploring the linkages in this chapter, we arrive at the proposition that individuals link through organizations to enable responsible management for the benefit of individuals. It is our responsibility to manage effective linkages, since as former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon stated – “We might have a plan B, but we do not have a planet B. I am confident that youth can and will make a difference in the fight against climate change. With dedication, passion and teamwork, we will make a notable difference—let’s preserve planet A” (https://www.un.org/youthenvoy/2014/09/no-planet-b-for-youth/).

Key Takeaways

Your key takeaways may be:

- that sustainability must involve stakeholders at all levels and forms of organizations;

- that CSR and sustainability movements need to be embedded in purposeful organizations and executed through appropriate leadership to ensure inclusivity and diversity are front and center.

If you are interested in the shared value literature, you should read Dembek, Singh, and Bhakoo (2016):

Reflective Questions

Take some time to reflect on how you would answer the following questions:

- In general, what is the role of corporations, NPOs/NGOs, government, and social entrepreneurial enterprises?

- Reflect on what it means and why it would be important to adopt a social constructivist view of society.

- At what level are sustainability principles incorporated into a firm? (mission, strategy, vision)

References used in the text – you are encouraged to consult these references through your institutional library services or through the internet

(1) https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/

(2) Freudenreich, B., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Schaltegger, S. (2020). A Stakeholder Theory Perspective on Business Models: Value Creation for Sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04112-z

(3) Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and Society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard business review, 84(12), 78-92.

(4) Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 62–77

(5) Houston, C., & Pinches, J. (2017). For Goodness’ Sake: satisfy the hunger for meaningful business (2nd Ed.). Chris Houston & Ogilvy & Mather.

(6) Golub, A., Mahoney, M., & Harlow, J. (2013). Sustainability and intergenerational equity: do past injustices matter?. Sustainability science, 8(2), 269-277.

(7) A fullsome discussion of the Charter with resources to the document itself can be found at https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/rfc-dlc/ccrf-ccdl/

(8) Daya, P. (2014). Diversity and inclusion in an emerging market context. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 33(3), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-10-2012-0087

(9) Adamson, M., Kelan, E., Lewis, P., Śliwa, M., & Rumens, N. (2021). Introduction: Critically interrogating inclusion in organisations. Organization, 28(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508420973307

(10) Ashraf, N., Pinkse, J., Ahmadsimab, A., Ul-Haq, S., & Badar, K. (2019). Divide and rule: The effects of diversity and network structure on a firm’s sustainability performance. Long Range Planning, 52(6), 101880.

(11) Al-Shaer, H., & Zaman, M. (2016). Board gender diversity and sustainability reporting quality. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics, 12(3), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2016.09.001

(12) Henry, L. A., Buyl, T., & Jansen, R. J. G. (2019). Leading corporate sustainability: The role of top management team composition for triple bottom line performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(1), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2247

(13) Alonso‐Almeida, M. D. M., Perramon, J., & Bagur‐Femenias, L. (2017). Leadership styles and corporate social responsibility management: Analysis from a gender perspective. Business Ethics: A European Review, 26(2), 147-161.

(14) Prahalad, C. K., & Hart, S. L. (2002). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Strategy + Business, 26 (Spring). Reprint 02106.

(15) Hart S. L., & Christensen, C. (2002). The great leap – Driving innovation from the base of the pyramid. MIT Sloan Management Review, 44(1), 51–56.

(16) Prahalad, C. K.. (2005). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Wharton School Publishing.

(17) Throsby, D., & Petetskaya, E. (2016). Sustainability Concepts in Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Cultures. International Journal of Cultural Property, 23(2), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739116000084

(18) Merino, R., & Gustafsson, M. T. (2021). Localizing the indigenous environmental steward norm: The making of conservation and territorial rights in Peru. Environmental Science and Policy, 124, 627–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.07.005

(19) Scheyvens, R., Carr, A., Movono, A., Hughes, E., Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Mika, J. P. (2021). Indigenous tourism and the sustainable development goals. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 103260.