Chapter 6 – Economic Considerations

Corporate social responsibility is a hard-edged business decision. Not because it is a nice thing to do or because people are forcing us to do it… because it is good for our business”

(Niall Fitzerald, Former CEO, Unilever)

Corporate social responsibility is not just about managing, reducing and avoiding risk, it is about creating opportunities, generating improved performance, making money and leaving the risks far behind. (Sunil Misser, Head of Global Sustainability Practice, PwC)

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will accomplish the following learning objectives:

- You will understand some of the economic underpinnings of responsible management (RM)

- You will understand the importance of a holistic view of RM through the triple bottom line of sustainability

- You will understand the relationship between financial performance and social responsibility and sustainability principles of RM

The world’s forests are being cut down in ways and at rates that make natural recovery difficult, if not impossible — to the detriment of the life, livelihoods and services they support. The solution lies in radically changing how we value and manage forests. Forests will persist only when we pursue a circular approach that maximizes their value to our collective well-being and eliminates the wastefulness we have come to accept as inevitable.

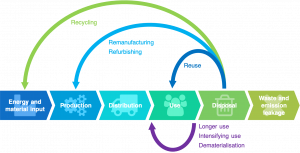

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a circular economy is based on the principles of designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use and regenerating natural systems: “Looking beyond the current take-make-dispose extractive industrial model, a circular economy aims to redefine growth, focusing on positive society-wide benefits. It entails gradually decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources, and designing waste out of the system.”

Canada’s forests are more than a part of our culture and national identity. They’re central to our food and water security, health and economy. With 9 percent of the world’s forests, and 24 percent of the world’s boreal forests, Canada can make important contributions to global well-being. Yet when we seek to measure the value of forests, we constrain ourselves by placing monetary value above all else. We see them for their timber, fruits and fibre — products that can be bought and sold. The recent federal budget framed the forest sector as an “important source of jobs and growth.” It is that, but the value forests bring to things like biodiversity, culture and quality of life, where monetized value can be harder to prove, is no less important to human well-being.

Once we are able to embrace the worth of forests beyond a dollar value, we can adopt a management strategy based on their overall contribution to society. We can make better plans that take into account and safeguard their effects on human well-being. That means moving from an industry that depends on raw materials and creates waste to one that uses design, technology and manufacturing innovation, to make the idea of waste obsolete — an industry that prioritizes recycling, reusing and remanufacturing throughout the life-cycle stages. An industry that, in short, can do more, and profit more, with less.

The impact of embracing a circular vision goes far beyond protecting any one forest.

It’s a rethink of the business model that is badly needed in Canada and beyond. This type of model, a central tenet of the circular and bioeconomy approaches, has been gaining ground throughout Europe. In 2015, the European Commission adopted an action plan to promote Europe’s transition to a circular economy. Finland, widely seen as a leader in this respect, set out its own national circular economy road map the following year. It is committed to creating more value with much less waste. It’s something we could learn from.

Canadian towns, cities and provinces have been taking action to reduce waste and move toward principles of a circular economy. Ontario’s Strategy for a Waste-Free Ontario takes steps to reduce waste and use waste more responsibly. Vancouver has a goal to cut down on landfill waste by 50 percent by 2020. The federal budget has proposed investing $251.3 million over three years in the forest sector, which would include support for innovation, renewable resources and clean growth. However, across the board, Canada lacks a comprehensive strategy for supporting this transition to a sustainable economy. Forests are a good place to start.

The impact of embracing a circular vision goes far beyond protecting any one forest. In Europe, circular economy strategies have been proven to create employment — with jobs that are well suited for the future — and to increase business competitiveness by reducing uncertainty around supply. A circular economy can also help mitigate the effects of climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which is in line with Canada’s clean progress agenda.

The theme of this year’s International Day of Forests was education. Let’s take the time to educate ourselves not only about Canada’s 347 million hectares of beautiful and essential forests but also about how we can keep our forests thriving into the future, long after the choices we make today take root.

Responsible management (RM) and its representation through CSR at the corporate level and sustainability via the triple bottom line (1) or the 5Ps of the United Nations Agenda implies that economics are interwoven in any discussion of RM.

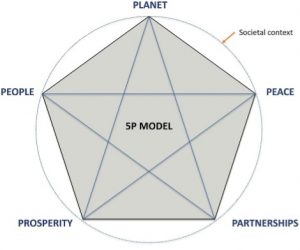

The triple bottom line is described as extending the concern of corporations beyond just profit as a singular bottom line into a concept that also includes planet and people (1). The three P’s as shown in Figure 1 are conceptualized as aspirational outcomes of businesses and organizations. From a holistic sense, integrating these concerns made sense in the late 1990s, particularly as ethical lapses, environmental disasters and social concerns impacted the operation of organizations.

As the basis for the UN Sustainable Development Agenda the triple bottom line was expanded to a 5P framework incorporating Peace and Partnerships in addition to Prosperity (profit), Planet, and People (see Figure 2). Seventeen goals of the Agenda include 169 targets with almost 232 economic indicators.

From an economic viewpoint, all SDGs are in some way involved even though they may have a focus on ecological or social objectives..

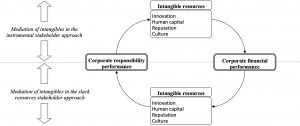

The link between a profitable and sustainable enterprise and its use of social responsibility has often been questioned and reviewed as lacking a direct relationship (2). Although a positive correlation between CSR and corporate financial performance (CFP) is not always clear from the perspective of individual organizations; on an aggregate basis the relationship is positive and may be an indirect relationship based on intangible factors linked to social and environmental progresses. Surroca and colleagues (3) describe a circular yet indirect relationship between CFP and CSR as described by the notions of leveraging intangible resources such as innovation, human capital, reputation and culture in a “virtuous circle”. For example, an excess of financial resources would allow the exploitation of intangibles to increase the CSR of an organization; and a commitment to CSR could leverage those intangibles to achieve better financial performance. This model as reproduced in Figure 3 from the original article is appropriate in a competitive environment as it identifies competences that could be used from a sustainability viewpoint and competitive viewpoint.

Friedman, a Nobel-prize winning economist, made an argument in a 1970 NY Times article from the last century (but still oft-repeated) that organizations needed to focus on the economic argument (4) rather than to concern themselves with ‘social causes’. However a closer reading of the article and listening to Friedman on pre-recorded episodes available through the internet does highlight the concern of economists for economic arguments. It must be remembered that during those times (in the early 1970’s), the socialist versus capitalistic models were in sharp contrast with looming global tensions between Soviet economies and Western economies threatening to break out into actual global nuclear conflicts.

Fast forward fifty years and the prevailing institutional opinions among the major global accounting firms relate to the importance of the triple bottom line and the 5Ps as embodied through the UN Sustainable Development Agenda. Reports and tools relating to the increasing awareness for the UN Agenda are available from major consulting organizations such as EY (https://www.ey.com/en_gl/sustainable-development-goals), PriceWaterhouse (https://datatech.pwc.com/SDGSelector/), and KPMG (https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/about/citizenship/global-goals-sustainable-development.html) among others detailing the prescriptive systems, and progress of firms in achieving the SDGs. The UN Global Compact, as another initiative promoting ten principles of doing business in a responsible manner (discussed in an earlier chapter) also regularly promotes the achievements of local firms and guides businesses towards achieving the SDGs (see for example the local Global Compact Network Canada website at https://globalcompact.ca/).

Institutional investors such as BlackRock Inc. with control over trillions of dollars in investment (as of 2020) have specifically signaled to shareholders and stakeholders a commitment to sustainability (https://www.blackrock.com/ca/investors/en/about-us/corporate-sustainability). From the practical to the academic, we can viewLaasch and Pinkse (5) describe four types of social responsibility models that firms embrace and explain this heterogeneity based on the context of the business environment that the firm finds itself in. They describe the models as embedding CSR through their “value proposition, creation, exchange, and capture” (5, pp. 16) in the following manner:

(1) As Discretionaries are located in an institutional space of homogeneous commercial demands, they morph responsibility elements to make commercial sense;

(2) Remedials’ heterogeneous institutional space is characterized by an ambiguity between commercial and responsibility demands, due to past responsibility transgressions which leads them to (over)compensate by intensively embedding responsibility;

(3) Reactives operate in a heterogeneous institutional space with less intense demands, allowing them to conform to achieve legitimacy with moderate intensity of responsibility embedding;

(4) Proactives share the same institutional space but choose to actively signal their leadership by intensively embedding responsibility to emerge as progressive responsibility leaders (5, pp. 16).

In addition to the high level impact investing that can be read about or seen in the current media, there are other specific actions that will impact the economic performance of firms. These ground level operational changes are reviewed below: life cycle pricing and the circular economy framework.

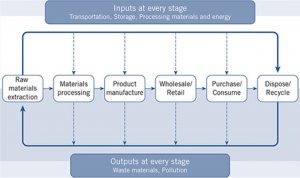

Life cycle pricing incorporates all inputs that leads to the production of a service or good into the pricing paid by the end user (see Figure 4). This includes the cost of replenishing the good consumed and by its very nature forces consumers to think and adjust their consumption behaviour (6, pp. 197-200). An example, although imperfect, could be the carbon tax applied at the gasoline pump as it tries to influence consumer behaviour by taxing the carbon content of fuel. Other organizations may also provide the information linked to processing along every step of their supply chain to highlight their steps towards sustainability (for an example of considering sustainability as integral to a corporate model listen to Interface’s late CEO Ray Anderson in this TedTalk https://www.ted.com/talks/ray_anderson_the_business_logic_of_sustainability).

Circular economy frameworks are another way of integrating sustainability and principles of CSR. In a circular economy (as seen in Figure 5), the focus is on re-integrating organic components into the value chain and re-using or refurbishing inorganic goods. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation is an excellent resource to understand this framework and the impact that one can have within this framework (https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/). This holistic system can benefit from active participation by organizations in a geographical cluster. For example, the Guelph-Wellington Circular Economy Initiative was funded through a Canadian $5 million dollar investment from the Federal Economic Development Agency (the result of a national competition) and is now focused on developing cooperative circular economy projects focused on food -related iniatives (https://guelph.ca/2021/04/growing-the-circular-economy-in-guelph-wellington-and-across-canada/).

Other Economic Considerations

Organizations work within the regulatory constraints of their economic environment and few are more important than legislation that is applied across an entire economy. One such legislation is the cap and trade and carbon pricing models that are used or have been used to varying degrees in Canada and internationally. The cap and trade system is essentially a trading system to trade on emissions that extend beyond a regulatory cap. However, as discussed in this chapter, Canada uses a carbon tax to incentivize a move away from carbon producing fuels. A Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act was federally legislated in 2018 and is progressively adding a surtax to fuel in order to change consumer habits and incentivize innovations (https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/pricing-pollution-how-it-will-work/putting-price-on-carbon-pollution.html).

Other regulatory constraints exist depending on the industry or market segment. The Canadian government provides guidance on responsible management through CSR via its CSR Guidebook (https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.629847/publication.html) which is applicable to organizations across Canada.

Organizations considering the economic aspect of the 5P framework, the triple bottom line, or economic sustainability need to implement processes at the outset of their organizational start-up if possible or consider their strategy through the lens of RM embodied through sustainability. At the outset, a sense of purpose interlinked with an organization’s management of its brand and culture are fundamental to the economic success of the firm (7).

Throughout its operation, organizations need to implement strategies with an awareness that adding them as ‘saddlebags’ to existing strategy will imply that the operations resulting from these strategies will be cut or curtailed at signs of economic distress (such as the recent covid-19 pandemic). However, if the strategies are adopted by embedding principles in the core of the organization then financial success can result (refer to the earlier discussion about the indirect relationship between CSP and CSR).

From an economic viewpoint in the context of an externally competitive world, embedding sustainability in the strategy and tactics of an organization can result in a competitive advantage particularly if that strategy leads to a core competence as described by Barney (8) through the VRIO framework of analysis.

Finally, consider that the competitive advantage (CO) of an organization can be described as a function of sustainable development (SD) which then links to a combination of organizational value (Ov), innovation (In), and social capital (Sk) (9).

CO=kSD=f(Ov; In; Sk)

This model is similar to the conceptualization provided by Surroca et al.(3) in that the strength of intangibles determine the competitive advantage of a firm. In this specific model, Sambiase et al. (9) focus on the importance of organizational values as determined by a sustainability mindset and the leadership that results from this purposeful consideration of sustainability.

In summary, responsible management and CSR impact organizations at an existential level, which is the economic underpinning of the firm. As Carroll (10)(11) described in his model describing the relationship between factors of CSR, the economic sustainability of the firm is an important pillar of the survival of any organization.

Key Takeaways

Your key takeaways may be that:

- that various economic models underpin responsible management such as the triple bottom line, the 5P framework, the life cycle model, the circular economy model;

- and that responsible management is also affected by leadership in the context of their organization’s environment (as a social entreprise or for profit firm).

You may want to read more Laasch & Pinkse (2020) to more fully inform yourself on business models:

Reflective Questions

Take some time to reflect on how you would answer the following questions:

- On an aggregate basis, what type of correlation exists between CSR and financial performance of a company?

- If the goal of business is to increase financial performance, how does integrating CSR into company principles contribute towards achieving this goal?

References used in the text – you are encouraged to consult these references through your institutional library services or through the internet

(1) Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: the triple bottom line of 21st century business. Wiley.

(2) Margolis, J.D., & Walsh, J. P. (2003). Misery Loves Companies: Rethinking Social Initiatives by Business. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(2), 268–305. https://doi.org/10.2307/3556659

(3) Surroca, J., Tribó, J. A., & Waddock, S. (2010). Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strategic management journal, 31(5), 463-490.

(4) Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). A Friedman doctrine–: The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In The New York Times (pg. SM17). Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

(5) Laasch, O., & Pinkse, J. (2020). Explaining the leopards’ spots: Responsibility-embedding in business model artefacts across spaces of institutional complexity. Long Range Planning, 53(4), 101891.

(6) Chandler, D. (2020). Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Sustainable Value Creation (5th Edition). SAGE.

(7) Houston, C., & Pinches, J. (2017). For Goodness’ Sake: satisfy the hunger for meaningful business (2nd Ed.). Chris Houston & Ogilvy & Mather.

(8) Barney, J. (1995). Looking inside for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Executive, 9(4), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.1995.9512032192

(9) Sambiase, M. F., Brito, E. P. Z., & Brunnquell, C. (2021). Sustainable Development Goals as a factor in organizational competitiveness and the role of sustainability leadership: a conceptual model. In Ritz, A.A., & Rimanoczy, I. (Eds.) Sustainability mindset and transformative leadership: A multidisciplinary perspective. Springer International Publishing AG. Chapter 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-76069-4_4

(10) Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G

(11) Carroll, A. B. (2016). Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 1(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6