Chapter 8 – Standards and Norms

“When sustainability is viewed as being a matter of survival for your business, I believe you can create massive change.” — Cameron Sinclair, architect and CEO of the Worldchanging Institute.

“Businesses must reconnect company success with social progress. Shared value is not social responsibility, philanthropy, or even sustainability, but a new way to achieve economic success. It is not on the margin of what companies do but at the center. We believe that it can give rise to the next major transformation of business thinking.” (Michael Porter)

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will accomplish the following learning objectives:

- You will understand the importance of standards and norms in reinforcing responsible management (RM)

- You will understand the linkages between reporting and good governance as part of the principles of RM

Example: Canadian CEOs out of step with stakeholders on ESG goals

By Erica Barbosa and Brian Gallant July 13, 2021

The pandemic has heightened awareness that continuing crises around climate, inequality and social cohesion are interconnected and must be addressed collectively. Economic thinkers from Mariana Mazzucato to Mark Carney agree that capitalism can no longer leave its negative impacts for government and philanthropy to solve.

The need to alter the economy’s trajectory toward an inclusive, equitable and sustainable future is behind escalating interest in environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing and reporting. To safeguard our collective future, corporate Canada needs to collaborate with community and public sectors to reshape markets in the public interest.

In a recent federal government report entitled, The Future of Business in Society, Coro Strandberg, co-founder of the United Way Social Purpose Institute (SPI), writes, “All signs point to successful businesses embrac[ing] a stronger role in creating value not just for themselves and their shareholders, but also for society and stakeholders [so that] nature is replenished and people and communities thrive.” While the conventional role of the United Way is to channel donations from companies to community organizations, the SPI offers assistance in the other direction — helping companies embed social values in their governance, business practices and reporting.

Too few of Canada’s corporate CEOs are paying attention. Fewer than half of those responding to the 2021 PwC CEO survey plan to spend more on ESG issues over the next three years. Over two thirds have yet to factor climate change into their risk management strategies.

Of 3000 Canadians surveyed by the Canadian Centre for the Purpose of the Corporation, 85 percent agreed business should put shareholder interests on par with those of communities, employees, customers and the environment. Further, 75 per cent want capitalism reformed to be more inclusive, sustainable and fairer — or be replaced.

ESG criteria provide starting points for this shift, but mere risk management is not enough. Allyson Hewitt, who coordinates the Business for Purpose Network at MaRS Discovery District told us, “The key is to define a company’s social purpose, align ESG activities around it, and engage with government and community partners around bold goals.”

The 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) outline a scientifically validated and widely endorsed set of bold goals for humanity. In many countries, they’re shaping public policy, investment and civic engagement in systemic change — but not yet in Canada.

According to John McArthur, Director of the Centre for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution and an authority on SDGs, Canada is struggling to gain traction on many SDGs: “The country’s corporate leaders need to play a much bigger role in helping to drive change,” he told us. Canada needs a corporate or tri-sector council on SDG implementation.

But not all CEOs are out of step; some are leading the way:

Advancing economic reconciliation

Reconciliation with Indigenous peoples includes making amends for the withdrawal of economic rights under the Indian Act. In cooperation with non-profit SHARE (Shareholder Research for Research and Education), the National Aboriginal Trust Officers Association and the Atkinson Foundation, TMX Group – which owns the Toronto Stock Exchange – has made a landmark commitment to this issue. Working with the Canadian Council on Aboriginal Business, TMX will set new targets around board and employee diversity and augment efforts to raise capital for Indigenous businesses.

Investing in employee equity

Non-profit Social Capital Partners (SCP) recently enabled 1200 employees of the US Taylor Guitar Company to purchase the company, in a $100 million ESOP (Employee Share Ownership Plan) deal financed by the Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan. As SCP founder Bill Young told us: “ESOPs enable wage earners to build equity and help ensure that good jobs stay in communities. Given how ESOPs have flourished in the UK and the US, their potential in Canada is enormous.”

Co-creating systemic change

The Transition Accelerator is a charity that creates values-based consortia to decarbonize Canada’s economy in the energy, transportation and building sectors. It does so by convening academics with businesses, communities and governments. CEO Dan Wicklum told us, “Centering social values in Canada’s transition to net zero is in the best interests of society. This in turn requires collaborative investment by philanthropy, the public sector, corporate finance and capital markets.”

We can and must do better. An economy that works for all and for future generations is within reach, if only the private sector works with community and public sector stakeholders to build it.

Reporting that you do what you have planned to do and that you plan what you will report, indicates a strong sense of governance for an organization. In the corporate world and in the not-for- profit world governance is critical towards achievement of strategic objectives. The article in the example pulled from various sectors mechanisms for reporting on what you do which is an important element of corporate governance.

What is commonly known as corporate governance could just as well be applied to organizational governance. It is that level of management that interfaces between its individual agents and stakeholders. It may be the top level management staff, the board of directors, or the principal or managing directors of an organization. Visser (1) in his CSR 2.0 book claims that sustainability and accountability are at the heart of corporate governance.

In effect, two of the key elements for effective governance are the transparency that is communicated and the accountability of the governance layer to its shareholders. To enable transparency and accountability within our societal context implies the use of reporting mechanisms. These mechanisms may be voluntary or regulated. For example, the UN Sustainable Development agenda has 232 indicators that are measured and reported back by national institutions to the supra-national statistical entities of the UN which then enables a fulsome measurement of the efficacy of the UN SDGs. These reports may or may not form part of national legal reporting requirements.

Of increasing interest are integrated reporting requirements emanating from financial market regulators. These reports increasingly require the explicit description of a company’s actions along the environmental (E), societal (S), and governance (G) dimensions of their performance. These ESG reports form an important component of the information disclosed to investors and signal an institutional compliance by organizations to increasing societal compliance to a triple bottom line perspective.

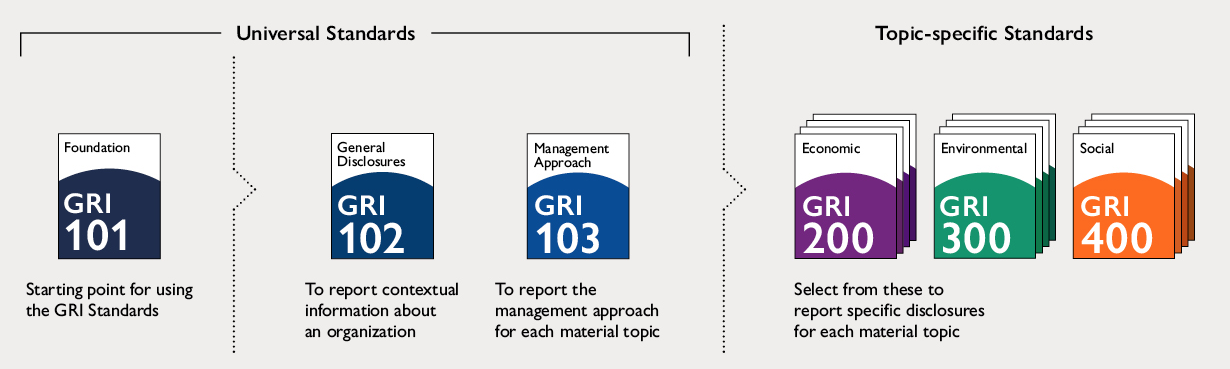

In the US, regulatory requirements from the SEC require a materiality risk assessments in the annual reports. In addition, Canadian reporting follows the guidance of the Accounting Standards Board (AcSB) and may adopt IFRS © standards for reporting as appropriate. On a global basis, the Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB) is responsible for developing the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI standards). The GRI provides standards related to transparency and accountability along ESG dimensions and provides common terminology and metrics to compare organizational performances (see Figure 1). It has been reported that most of the global top Fortune 250/500 companies in the world use GRI metrics to provide integrated reports of their activities or else specifically align their activities with UN SDGs. The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) has also published a framework detailing how to structure financial and ESG metrics (first published in 2013, it was updated in 2021 and can be obtained by accessing https://www.integratedreporting.org/resource/international-ir-framework/).

Judy Kuszewski is Chair of the Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB), the independent entity that sets the GRI Standards. She said about the new GRI 13 standard:

It’s clear that ‘business as usual’ by companies will not result in the sustainability transformation we need to see. Shining the spotlight on the most significant impacts of organizations involved in crop cultivation, animal production, fishing or aquaculture, GRI 13 brings the clarity and consistency needed to inform responsible decision making. (https://www.globalreporting.org/news/news-center/advancing-sustainable-production-on-land-and-sea/)

The Canadian government provides a guide through its Government of Canada website that details reporting guidelines for any business involved in CSR. It can be accessed through this link: (https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/csr-rse.nsf/eng/h_rs00599.html#s3.3.4). Pay particular attention to sections 3.3 and 3.4 of this guide as it outlines prescriptively, CSR reporting and its relationship with legal constraints.

Finally, the use of standards and norms form a critical aspect of reporting and ultimately the transparency and accountability of the organization.

Standards are driven by stakeholder needs and often result in institutional isomorphism in the way electrical installations are done, construction is assembled, trade is conducted, goods are manufactured, and even guide the professionals like engineers, accountants, and medical practitioners. When standards are legislated, then accountability to the standards is expected as a legal requirement whereas when they are voluntary, stakeholders may be expecting compliance or at least reporting to those standards. There are even standards designed to integrate CSR into an organization such as ISO-26000. Waddock (2) discussed the institutionalization of various standards and norms into organizations. Integrated reporting mechanisms are also guided by standards whether voluntary or legislated to inform stakeholders and signal organizational sustainability and CSR initiatives.

As transparency and accountability are the key concepts to reporting frameworks, it is wise to reflect on the type of organizations that one belongs to and the regulatory or voluntary requirements that need to be complied with in order to achieve societal acceptance and to signal a commitment to responsible management, CSR and sustainability.

Key Takeaways

Your key takeaways may be that:

- Standards and norms whether regulated or voluntary are important elements in the reporting of sustainability and CSR; in effect showing the outcomes and guiding the process of responsible management;

- Second, that corporate governance is guided by accountability and transparency so that all stakeholders feel engaged in the organizational purpose and drive towards sustainability.

There are so many directions that can be taken in this chapter.

For those with an accounting and finance focus, you may be interested in reading Zadek (1998) and his article on balancing business ethics and accountability or Milne and Gray (2013) in their linking of the triple bottom line with the GRI and sustainability reporting;

Those who are interested in the Canadian perspective with respect to disclosure, should read Dilling and Harris (2018) as they explored financial and sustainability reports by Canadian companies:

Adopting the SDGs is the themeof a fascinating article by Rosati and Faria (2018) and a variety of institutional norms, standards and guidelines is discussed by Waddock (2008):

A critical view of sustainability disclosure and a possible theoretical lens to see how organizations are constrained by societal viewpoints is described by Cho and colleagues (2015):

Reflective Questions

Take some time to reflect on how you would answer the following questions:

- What are two of the key elements for effective governance?

- How is transparency and accountability enabled?

- What are the different dimensions of integrated reporting that are important for organizations to report on and disclose

References used in the text – you are encouraged to consult these references through your institutional library services or through the internet

(1) Visser, W. (2011). The Ages and Stages of CSR: Towards the Future with CSR 2.0, Social Space 2011.

(2) Waddock, S. (2008). Building a New Institutional Infrastructure for Corporate Responsibility. Academy of Management Perspectives, 22(3), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2008.34587997