Chapter 9 – Sustainable Development

“We are living on this planet as if we had another one to go to.”

– Terry Swearingen, Nurse & Winner of Goldman Environmental Prize in 1997

“Our biggest challenge in this new century is to take an idea that seems abstract – sustainable development – and turn it into a reality for all the world’s people”

– Kofi Annan – Former secretary general of the United Nations

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will accomplish the following learning objectives:

- You will understand principles of sustainability as applied to responsible management

- You will integrate various concepts of sustainability including conceptions with indigenous considerations, and global framing of sustainability challenges

Example: Trade agreements must be climate-focused, new IPCC report shows – Governments need to repair the incoherence between climate objectives and the emissions-intensive trajectory of the global economy

By: Sabaa Khan February 28, 2022

Source: https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/february-2022/trade-agreements-climate-action/

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report gives more stark evidence that ecosystems and human societies are on the brink of collapse, and that our efforts to adapt have been no better than efforts to mitigate the crisis.

The cascading impacts of an overheating climate will especially affect the most vulnerable — people already suffering extensive loss and damage. The persistence of global inequalities in socioeconomic development will lead to millions more people facing energy, food and water insecurity.

The recent report, Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, calls for transformational change in the way we produce and consume, and points to the dire need for governments to invest more in adaptation. But domestic and international climate policy alone can’t solve this problem. Governments need to acknowledge the profound impact of their trade and investment policies on climate change, and reverse longstanding patterns of deep incoherence between our climate policy objectives and the emissions-intensive trajectories of the global economy.

This is the second of three working group reports, which along with three special reports and a synthesis report make up the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment (AR6). The first, released in August 2021, assessed the physical science, showing climate change is widespread, rapid and intensifying. The third, expected in March, will focus on climate change mitigation.

The latest report signals that behavioural changes are required throughout society — from individuals and communities, to institutions and governments. But it’s clear that, above all, governments must assume with far greater urgency their shared responsibility to set the parameters of the global economy to enable everyone to adopt more climate-sensitive lifestyles and ensure global inequalities don’t worsen.

As one of the largest per capita greenhouse gas emitters and exporters of coal, oil and gas, Canada has a major role to play. The report should motivate government to enhance the international co-operative dimensions of its National Adaptation Strategy to assume its fair contribution to international climate finance and, most importantly, to mobilize its trade and investment policies as real vectors for climate action.

Although multilateral and bilateral agreements for sustainable trade and investment are key to changing global industrial production and consumption patterns, trade wasn’t a major topic at the 2021 COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. But commitments made by Canada and others, including those aimed at halting deforestation and ending international fossil fuel project financing, have clear links to trade and investment policy.

Just a few days after COP26, Canada and the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) announced negotiations for a comprehensive free trade agreement. While these could be an opportunity to create trade rules and practices aligned with international and domestic climate policy objectives, climate change wasn’t mentioned in the international trade minister’s notice of intent to enter negotiations. The minister’s mandate letter incorporates expectations linked to advancing Canada’s climate change commitments, but it doesn’t include any explicit references to climate change regarding free trade opportunities.

A joint economic analysis by the trading partners projected that a trade deal with ASEAN could increase Canada’s GDP by US$2.54 billion, but it offers little insight into how the projected growth relates to and may negatively affect the climate, nature and pollution crises.

In light of the recent IPCC reports, Canada’s so-called progressive approach to free trade negotiations is outdated and risks exacerbating the climate crisis. Canada should follow the transformative lead of New Zealand, Costa Rica, Fiji, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland: In 2019, they started negotiating an Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability, intended to bring together climate, trade and sustainable development agendas.

The ACCTS negotiations cover removal of barriers to environmental goods, binding commitments on environmental services, efforts to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies and guidelines for high-integrity eco-labels. Canada should draw on this innovative approach and reorient its trade policy agenda to centralize the economic, social and environmental threat of the climate crisis. To ensure that greening trade policy doesn’t impact poor countries, it must also incorporate rules to promote transfer of sustainable technologies and increase access to intellectual property.

In the face of an existential threat, there’s no room for 20th-century approaches to international trade. As a globally interconnected society, transnational partnerships and global solidarity are key. We need a vastly different kind of economic globalization, an overhaul of the fundamental principles that underlie our commercial relations, including abandoning investor-state dispute settlement processes.

International trade was promoted after the Second World War under the belief that greater economic interdependence would reduce protectionism and war, and foster peace and prosperity. Sadly, the way we’ve liberalized trade has increased health inequities in the globalized workforce and worsened the climate, nature and pollution crises. Exploitation-based growth has fuelled global conflict and inequalities. We must act now to avoid history repeating itself.

Responsible management integrates concepts of sustainability into its principles. The IPCC report described in the example above is an outcome of global concern with the state of our climate which is the result of sustainability efforts (or lack of them) by global human society.

Remember that words and terms used in the sustainability literature have roots that may impart meaning a multitude of meanings. However, our social constructivist approach to responsible management means that we need to consider the meaning of sustainability within today’s context and its relevance to societal thinking. In this chapter we look at the environmental considerations relating to sustainability with the constant awareness that responsible management holistically integrates principles covered in corporate social responsibility, in ecological sustainability, and social purpose actions. We will start with a broad view of our impact on the planet’s ecology, discuss the reports underpinning our awareness of our own anthropogenic impacts, and drill down to collective considerations often found trough indigenous considerations and our own individual considerations.

It is widely reported that we have reached the Anthropocene age where our human actions (or inactions) create permanent change to the planet ecology. In the past 100 years, human activity along industrial, agricultural and societal dimensions have impacted the complex environment and relationships of the globe to a point that threatens its resiliency (1)(2).

In the colonial viewpoint, human economic development is a zero-sum contest when contrasted to ecological considerations (3). Human activities in this context used resources extracted in some way from the planet to better the well being of society. It is debatable as to when this activity materially impacted the earth, but one could consider the example of the tragedy of the commons (4) where mono-agricultural and farming activities exhausted the local availability of certain foodcrops and denuded landscapes to benefit the farming of sheep. As an isolated incident in the geologic timescale of the earth’s development, the tragedy of the commons could have been healed over the long term through natural forces. However, the struggle to gain greater resources and human ingenuity accelerated the need for more planetary resources to the point where the transition from an agrarian economy exploded into the industrial revolution – the ‘discovery’ of new worlds by Western colonials, and possibly worst of all, the subjugation of local indigenous societies by these colonials in their effort to acquire more resources and ‘riches’ for themselves.

It is argued that in the past 100 years, more damage has been done to the planet than in the previous 200,000 years of human evolution. Part of human evolution includes the globalization of communication and the increasing awareness of our impact on the planet. It could be argued that the severity of our impact was brought to light most universally when nations realized that we were actually creating holes in our ozone layer due to our polluting air-borne fluorohydrocarbons. Global conferences generated agreements such as the Montreal Protocol in 1987 to address ozone depletion, the Rio Agenda 21 of 1992 to address sustainable development which included environmental concerns, the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 to rein in and provide regulatory constraints on greenhouse gas emissions, and various global conferences to address what we view as an existential crisis to human survival (more about these Conferences of Parties – COP later).

In the same time frame, the United Nations, commissioned a report by the Brundtland Commisision into sustainable development which resulted in an oft-quoted definition of sustainable development as development “that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (5). At the Rio Conference in 1992, nations discussed and agreed to efforts in promoting goals that would remedy economic and social disparities along with what was becoming viewed as environmental challenges and promoted this Agenda. In 1997, Secretary General Kofi Annan led a Millennium Assembly towards reforming the UN mission towards environmental and societal positive changes resulting in the Millennium Goals in 2001. These goals as described in the list below address human needs (goal 1, 4, 6), societal needs (goals 2, 3, 5), environmental needs (goal 7) and partnerships towards economic development (goal 8). Hulme and Scott (6) provide a summary of the development of the Millennium Development goals and how their lack of specificity made them difficult to assess their success. The full list of Millennium Development Goals can be seen below and more information can be found at (https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/).

The 8 Millennium Development Goals are to:

-

- Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger

- Achieve Universal Primary Education

- Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women

- Reduce Child Mortality

- Improve Maternal Health

- Combat HIV/AIDS, Malaria and Other Diseases

- Ensure Environmental Sustainability

- Global Partnership for Development

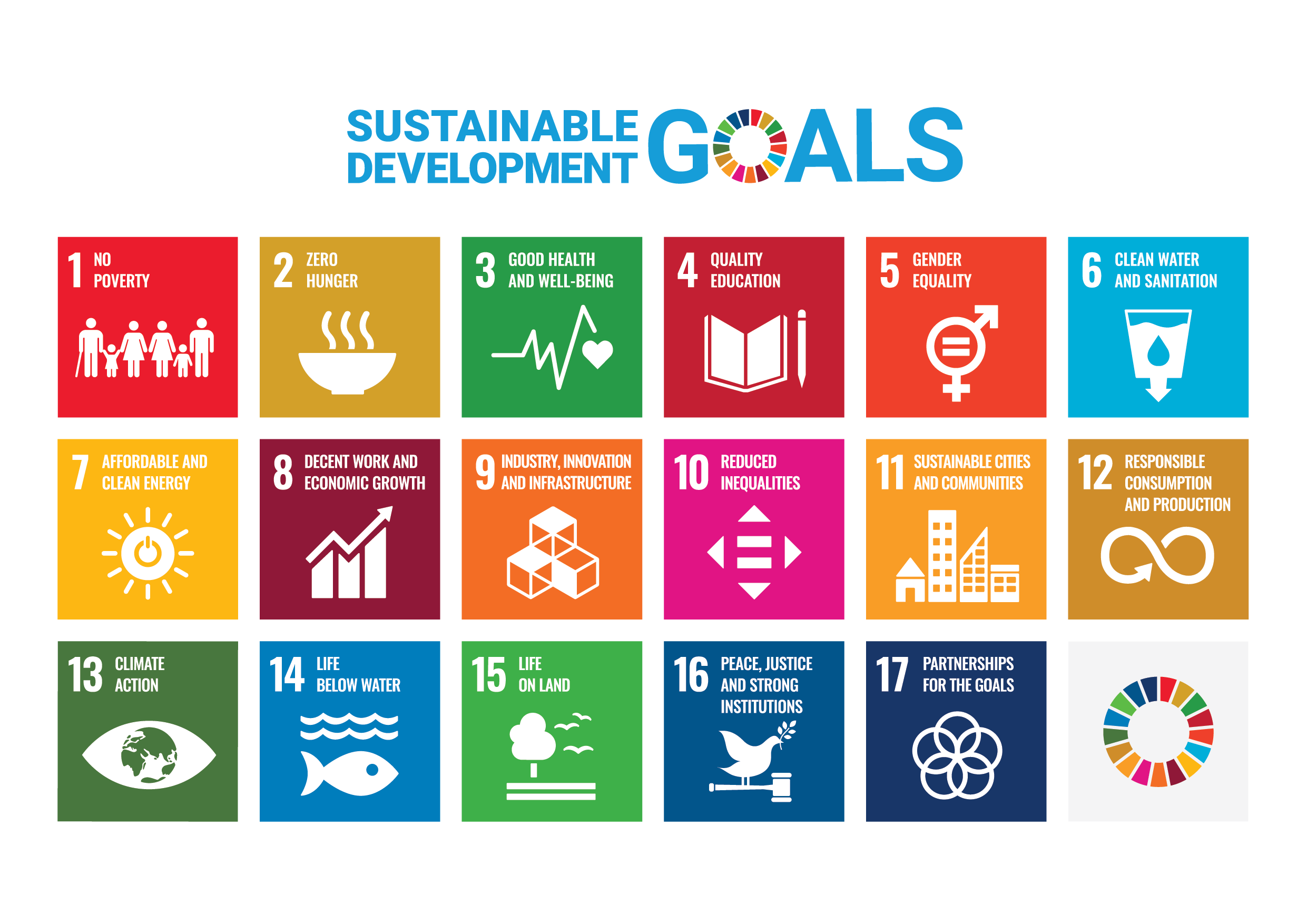

Through the experiences of the Millenium Goals, the UN with the guidance of Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon created working groups to improve the effectiveness of the goals and to provide measurable indicators towards their achievement. This resulted in the UN Sustainable Development Agenda 2030 which was composed of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (see Figure 1) described through 169 targets and over 232 measurable indicators. These SDGs were meant to act as supra-national objectives that would be monitored by national governments to be reported back to the UN on a yearly basis. The responsibility for achieving the goals was not defined to any single entity but instead was a collective ‘task’ which resulted in activist organizations putting pressures on institutions and corporations, on standard setting organizations providing guidances, norms and standards to voluntarily or regulatorily control the achievement of the goals – enforcing principles of transparency and accountability.

In a more existential vein as described by this chapter’s example the UN also has a working group, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), that was tasked with reviewing and sharing knowledge about climate change resulting from human impact. They provide scientific documenting of the state of the planet. Since 1988, the IPCC has released periodic reports that have been the guiding documents for UN Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings dealing with environmental concerns and climate change. The COP 21 conference in Paris in 2015 was famous for its global unanimity in agreeing to address climate issues by commitments by all participating nations to restrict their carbon equivalent emissions and restrict global warming to an average of less than 2 C by the mid 21st century. The IPCC report of 2022 and the COP26 conference in Glascow however recognized that this target may not be achieved which resulted in stakeholder activism and demonstrations across the globe. This IPCC report, the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC can be accessed through (https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/) in a variety of formats. Some of the key points described in the summary for policy makers are (note that the summary report is over 40 pages long and so only a few of the key points are listed below):

- that climate change has caused drastic impact on ecosystems globally with disproportionate impact on indigenous communities world wide,

- that advances to meet the SDGs are negatively impacted by the severity of climate change outcomes,

- that in the short to mid term (2021-2040) and in the mid to long term (2040-2100), climate change due to increases of 1.5C or higher will increase risks to biodiversity, natural resource availability, and human socio-economic conditions,

However, the IPCC also suggests that:

- adaptation options are possible and that current societal awareness and actions by most countries (“at least 170 countries”) has resulted in policy changes and adaptation policies,

- that multi-sectoral adaptations and conservation measures can be effective in reducing risks,

- but that increasing global warming outcomes may constrain human and natural system adaptation unless institutional and political mobilization of resources are used to increase resilience and improve sustainability.

Throughout this increasing awareness of ecological impact by neo-colonial powers and by emerging nations, there has been a growing awareness of the holistic perspectives of indigenous peoples when it came to sustainability. Although, there are always exceptions to this consideration, it is believed that most indigenous peoples that were colonized or are undergoing colonization, lived traditions that were more in harmony with the planet than current traditions.

Kealiikanakaoleohaililani and Giardina (7) describe foundations of indigenous sustainability as part of the relationship and sacred exchanges that happen between human and natural resources. In South America, for example among the indigenous peoples of Peru, their activism has conceptualized them as environmental stewards particularly in the Amazonian jungle where territorial rights are in danger (8). Quechuan culture in the Andes, also promotes a framework of relationship with nature. There is a term for the earth which implies a maternal relationship with it – Pachamama; and a thankfulness for its abundance in providing food for its carers. Some of the earliest peoples in Peru practiced sustainable agriculture that leveraged the cultivation of crops along elevations and conditions in traditional ways considered as subsistence farming by neocolonials but that is holistic and integrated with a deep respect for nature and the earth (9).

In North America, the indigenous peoples and their way of synergistically relating to Turtle Island (as the North American continent is known by many peoples) and our awareness of this relationship has led to conflicts, reconciliations, and further conflicts into an awareness of other ways of dealing with the land than in a purely one-way manner or zero sum manner. If you are interested in this perspective, there are a variety of indigenous authors who can provide insights from the ecological viewpoint (Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer) or a societal viewpoint documenting the sundering of this relationship and struggles to re-establish it (Five Little Indians by Michelle Good). As in all societal groups, there are a multiplicity of views regarding sustainability when balanced with economic or health-related well-being. For example, some of the clearest examples are the discussions and challenges when dealing with extractive industries where some indigenous peoples will accept or reject certain capital developments along a spectrum of reasons ranging from traditional to pragmatic economics (for an example of this difference in perspectives read about the conflict with the Coastal GasLink pipeline in Wet’suwet’en territory in Western Canada by accessing CBC News at https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/wet-suwet-en-coastal-gaslink-pipeline-1.5448363).

In our next chapter, we will further explore sustainable development with a focus on human organizations and from the social aspect of this definition.

Key Takeaways

Your key takeaways may be that:

- environmental sustainability is interlinked with a global complex adaptive system that is framed by our responsible management of societal and natural resources

- second, that supra-national efforts and initiatives exist but can only be implemented through activism at various levels of operationalization.

If you are interested in the transition from the Millenium Goals to the SDGs, you may want to read Sachs (2012) in:

Sachs, J. D. (2012). From Millennium Development Goals to Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet, 379(9832), 2206–2211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60685-0

You are encouraged to read the impact of the Anthropocene age as related in this invited paper by Steffen et al. (2011):

Steffen, W., Persson, Å., Deutsch, L., Zalasiewicz, J., Williams, M., Richardson, K., Crumley, C., Crutzen, P., Folke, C., Gordon, L., Molina, M., Ramanathan, V., Rockström, J., Scheffer, M., Schellnhuber, H. J., & Svedin, U. (2011). The Anthropocene: From Global Change to Planetary Stewardship. AMBIO, 40(7), 739–761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-011-0185-x

The ‘tragedy of the commons’ from a sustainable development viewpoint can be viewed as one of three game theories in addressing sustainable development as described by Lozano (2007) [ the other two scenarios are the ‘prisoner’s dilemma’ and the ‘Nash equilibrium’]:

Lozano, R. (2007). Collaboration as a pathway for sustainability. Sustainable Development, 15(6), 370–381. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.322

From an economically based institutional perspective, Daddi et al. (2020) describe how companies adopt climate actions based on institutional pressures:

Reflective Questions

Take some time to reflect on how you would answer the following questions:

- Identify the main consequences stemming from the transition of an agrarian economy to the industrial revolution.

- The responsibility of achieving the SDGs is not placed on any single entity and the methods to achieve the goals remains open. Reflect on how this can be seen as both advantageous and a hinderance for achieving the goals.

- Review the summary report for IPCC 2022. List some of the key conclusions of the report and what should society do to accomplish what is needed to avoid a global climate catastrophe.

- Identify and reflect on some of the holistic perspectives of indigenous peoples as it relates to sustainability.

References used in the text – you are encouraged to consult these references through your institutional library services or through the internet

(1) Steffen, W., Persson, Å., Deutsch, L., Zalasiewicz, J., Williams, M., Richardson, K., Crumley, C., Crutzen, P., Folke, C., Gordon, L., Molina, M., Ramanathan, V., Rockström, J., Scheffer, M., Schellnhuber, H. J., & Svedin, U. (2011). The Anthropocene: From Global Change to Planetary Stewardship. AMBIO, 40(7), 739–761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-011-0185-x

(2) Steffen, W., Crutzen, P. J., & McNeill, J. R. (2007). The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 36(8), 614–621. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[614:TAAHNO]2.0.CO;2

(3) Parks, B. C., & Roberts, J. T. (2010). Climate Change, Social Theory and Justice. Theory, Culture & Society, 27(2–3), 134–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409359018

(4) Hardin, G. (2009). The Tragedy of the Commons *. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research, 1(3), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/19390450903037302 [ *Originally published in: Science, Vol. 162, No. 3859 (13 December 1968), pp. 1243–1248. Reproduced with kind permission of the American Association of the Advancement of Science]

(5) Brundtland, G., Khalid, M., Agnelli, S., Al-Athel, S., Chidzero, B., Fadika, L., Hau, V., Lang, I., Shijun, M., Morino de Botero, M., Singh, M., Okita, S., and Others, A. (1987). Our Common Future (‘Brundtland report’). Oxford Paperback Reference. Oxford University Press, USA.

(6) Hulme, D., & Scott, J. (2010). The Political Economy of the MDGs: Retrospect and Prospect for the World’s Biggest Promise. New Political Economy, 15(2), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563461003599301

(7) Kealiikanakaoleohaililani, K., & Giardina, C. P. (2016). Embracing the sacred: an indigenous framework for tomorrow’s sustainability science. Sustainability Science, 11(1), 57-67.

(8) Merino, R., & Gustafsson, M. T. (2021). Localizing the indigenous environmental steward norm: The making of conservation and territorial rights in Peru. Environmental Science & Policy, 124, 627-634.

(9) Sumida Huaman, E. (2016). Tuki Ayllpanchik(our beautiful land): Indigenous ecology and farming in the Peruvian highlands. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 11(4), 1135–1153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9622-z