9a: Economic Costs and Benefits of Organic Agriculture

Written by Eric Topp

Introduction

When assessing the economic costs and benefits of organic agriculture, multiple factors need to be considered (Reganold and Wachter 2016). The economic costs and benefits of organic agriculture are also commonly compared to those of conventional agriculture. One of the major factors for consideration is the costs per unit of production. This is important to consider because the income per unit of production needs to be greater than the cost per unit of production for the producer to make a profit.

A second major factor that needs to be considered when determining the economic costs of organic agriculture is the overhead and variable costs (Stanhill 1990). These costs need to be conservatively measured, as these costs can vary significantly. A significant change in costs will, in turn, significantly affect the overall profit of the crop. It is crucial to consider all costs to accurately determine the overall economic profit of the crop.

When calculating the income and benefits of organic agriculture, it is important to consider both tangible and intangible factors. In an ideal situation, the income will be much greater than the total costs. The farmer would be able to make a profit and it would be more beneficial economically for them to produce organic crops. Along with measurable income, other benefits should also be considered. These benefits often are not assigned a specific dollar figure, and some are worth more to certain farmers. For example, the nutrients in the soil may be more beneficial to farmers who are not able to apply their own manure to the soil and instead have to purchase nutrients for their crops (Seufert and Ramankutty 2017).

Finally, it is important to properly interpret the profits and losses in organic agriculture. When calculating a per bushel figure, it is very easy to see a large profit margin (Seufert et al. 2012). However, when calculating a per-acre figure, it is sometimes difficult to show a profit in dollars. This is where organic agriculture benefits come into the equation. It is important to factor these often-unmeasurable benefits into the equation to properly determine the overall profit of organic agriculture production. It is also important to properly understand and interpret the losses associated with organic agriculture, including pests, yield, and emissions.

Economic Measures

It is extremely important to completely and accurately assess all costs associated with organic agriculture production to properly determine the total cost per unit of production. To do this, all costs including seed, nutrients, fuel and machinery, insurance, taxes and other related land costs, storage, grain drying (where applicable), time and labour all need to be considered. Some of these costs, including time and labour, are often not factored into the equation, resulting in an inaccurate cost per unit of production.

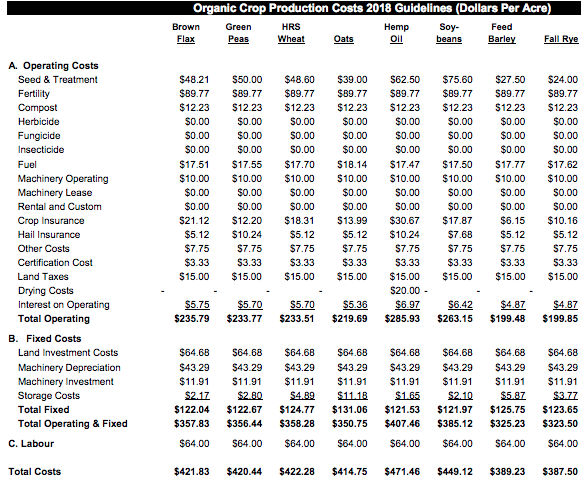

Table 1 actively and extensively outlines costs associated with the production of organic agriculture (Manitoba Agriculture Farm Management 2018). These costs were calculated based on organic agriculture production in Manitoba, Canada in 2018. In the example of soybeans, the total of all costs included in Table 1 is almost $450.00 (Government of Manitoba, Agriculture Farm Management 2018). It is important to know this information when calculating the total profits of the crop. If the costs are not properly determined, the profit calculated will not be accurate. To determine the economic costs and benefits of organic agriculture, the total costs of production must be accurate (Muller et al. 2017).

Along with determining total overall costs, it is important to have accurate reports throughout the year (Vanrolleghem and Gillot 2002). This is very important to have, as the farmer will have a better understanding of when their costs will occur. For example, the cost of seeds may come in the winter before the growing season, or in the spring before planting. The cost of fertilizer application will vary based on the individual field and crop. Some nutrients may be applied prior to the crop being planted, during planting, or throughout the growing season.

Other costs such as land rent and machinery payments may need to be made regularly. These costs need to be laid out and organized throughout the year so that the producer can understand when and where costs will be incurred (Vanrolleghem and Gillot 2002).

Organic agriculture producers need to know when their costs will occur because it is very likely that they do not receive a regular income. This means that they will be paid based on what they produce, and therefore will not be paid regularly like many jobs are. Because income is not often received, organic agriculture producers must know when and where their costs will occur so they can budget accordingly. Organic farmers rely on economic measures to ensure a successful year, so they must be accurate.

Overhead Costs Compared to Variable Costs

Overhead costs and variable costs are important factors to consider when considering organic agriculture. To begin, overhead costs remain constant while variable costs can change depending on market fluctuations. In organic agriculture, overhead costs would be higher compared to variable costs for several reasons. Overhead costs such as equipment costs and maintenance would be high because organic production devotes more resources to mechanical control of weeds and pests rather than chemical control. In comparison, variable costs such as labour would also be high because of the extra time needed to crimp the cover crops for weed suppression. Farming organically increases labour costs by (7-13%). The reason for the increase is that weed control is completed without the use of pesticides or insecticides so there is no use for an automated sprayer, instead, they manually remove weeds from the field.

The overhead cost for organic farming is similar to conventional farming. There are your main costs that every farmer must pay, these include costs of equipment, costs of buildings, property taxes, and costs of seeds. These costs are the most common among farmers, although, every farmer runs their operation differently, so they have different expenses that they need to pay.

Income and Benefits

When it comes to income, there are some slight differences between the income that conventional agricultural producers experience and the income that organic agriculture producers experience (Batte et al. 1993). It works similarly, but organic agriculture producers experience a premium when selling their crops because they produce organically grown products. This premium is necessary for organic farmers to make a profit at the end of their growing season. This is because organic crops typically produce lower yields compared to conventional crops (Connor 2008).

The benefits of organic agriculture production can vary between producers, depending on their specific operation. Some organic agriculture producers have greater benefits associated with nutrients (Piya et al. 2018). The soil nutrients available in organic agriculture can significantly decrease the costs of nutrient inputs. Organic farmers who have manure that can be applied to their crops do not have high nutrient costs (Piya et al. 2018).

Interpreting Profits and Losses in Organic Agriculture

On an Organic Farm, the only income is when you sell your crop. Every year the amount of income from the crops will change. There are a couple of factors on why this is; some years there is a lack of rain or too much rain and this will alter the way the crop grows. Another reason that the income can be varied is the price of the crop per bushel. For example, the price of organic soybeans is averaging around $26-$28 (OrganicBiz 2021). When a farmer finds a price that they are satisfied with, they will book a certain number of crops by the bushel. Once they are locked into that contract, they grow their crop to fill those contracts and receive their payment. If a farmer does not want to sell their crop right away, they can store what crop they do not want to sell and wait for a better price.

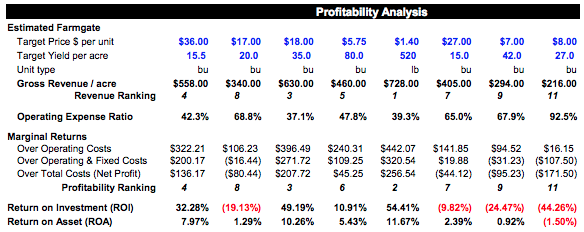

In Table 2, estimated profits are outlined for various organic crops (Manitoba Agriculture Farm Management 2018). This table accurately shows a profitability analysis that organic agricultural producers can use when working towards determining the economic costs and benefits of their specific operations. They can see accurately predicted profits for their specific crops which will help them determine their year-end profits. This will also allow them to have a more specific budget for their year (Manitoba Agriculture Farm Management 2018).

Farming has a lot of strong years but there are always years where crops do not turn out the way the farmer wants them to. Once a farmer has signed a contract, they have to fill it somehow; if he does not create enough crops throughout the year the farmer will have to buy beans to fill the contract. There is another way that a farmer can lose out on money. Before a farmer signs a contract, they will look up the price of beans and decide if that is a good price. Once he has signed away all of his beans, if the price continues to go up the farmer cannot continue buying contracts. The farmer will now just settle for the price of the beans that he agreed to in the contract.

References

Batte MT, Forster DL, Hitzhusen FJ. 1993. Organic agriculture in Ohio: an economic perspective. Journal of Production Agriculture 6(4), 536 – 542. https://doi.org/10.2134/jpa1993.0536

Connor DJ. 2008. Organic agriculture cannot feed the world. Field Crops Research 106, 187 – 190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr2007.11.010

Government of Manitoba, Agriculture Office. 2018. Guidelines for estimating organic crop production costs in Manitoba. https://www.gov.mb.ca/agriculture/business-and-economics/financial-management/pubs/cop-crop-organic-production.pdf

Muller A, Schader C, Scialabba NE, Brüggemann J, Isensee A, Erb K, Smith P, Klocke P, Leiber F, Stolze M, Niggli U. 2017. Strategies for feeding the world more sustainably with organic agriculture. Nature Communications 8, 1290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01410-w

OrganicBiz. 2021. Organic price quotes: Late January. https://organicbiz.ca/organic-price-quotes-late-january-5/

Piya S, Shrestha I, Gauchan DP, Lamichhane J. 2018. Vermicomposting in organic agriculture: influence on the soil nutrients and plant growth. International Journal of Research 5(20), 2348-6848. https://doi.org/2348-795X

Reganold JP, Wachter JM. 2016. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nature Plants 2, 15221. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2015.221

Seufert V, Ramankutty N. 2017. Many shades of gray – the context-dependent performance of organic agriculture. Science Advances 3(3), e1602638. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1602638

Seufert V, Ramankutty N, Foley J. 2012. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 485, 229 – 232. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11069

Stanhill G. 1990. The comparative productivity of organic agriculture. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 30(1-2), 1 – 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8809(90)90179-H

Vanrolleghem PA, Gillot S. 2002. Robustness and economic measures as control benchmark performance criteria. Water Science and Technology 45(4-5), 117 – 126. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2002.0565