6d: One Health Interactions: Health of Soil, Plants, Animals, and People

Written by Amy Chesbro

Introduction

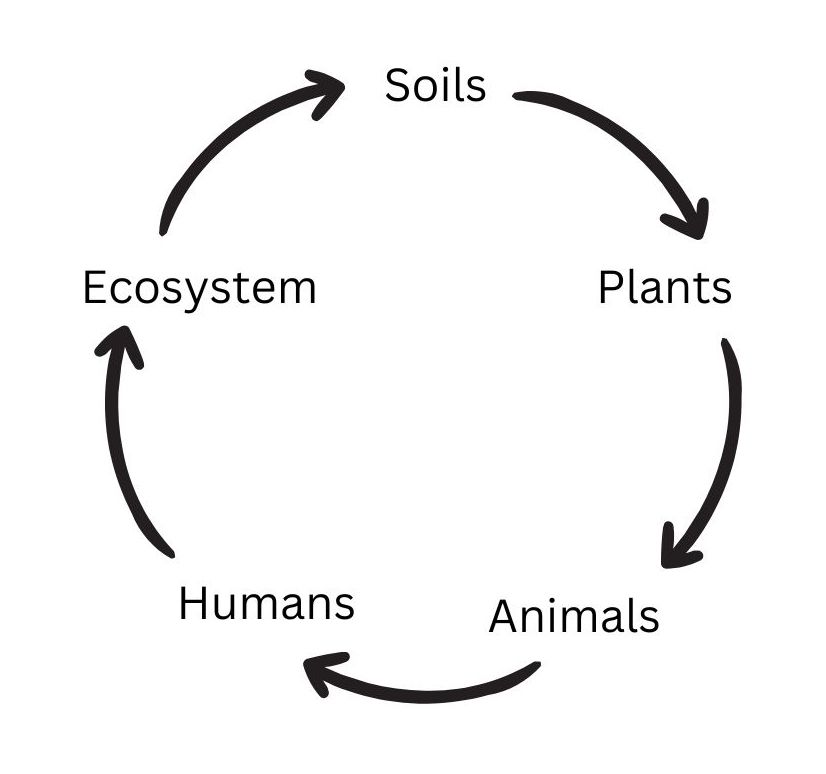

There are five domains within the system of agriculture – soil, plants, animals, humans, and ecosystems. Each domain is directly impacted by the others and if there is an imbalance in one domain, there is an imbalance in all domains. This concept is often referred to as ‘One Health.’ One Health, as defined by the CDC (Centers for Disease Control. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov, accessed 2021), is, “ an approach that recognizes that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment.” This is an important concept as it promotes the health of animals, humans, and the shared environment and prevents the transfer of diseases between them (One Health Basics 2018). The author of The Living Soil (1942), Lady Eve Balfour, proposed a statement of indivisibility – “the health of soil, plant, animal and man is one and indivisible” (Vieweger and Döring 2015). This statement can be interpreted in two ways – as a connectivity hypothesis or a non-separation imperative (Vieweger and Döring 2015). The first interpretation implies that health is linked among the domains and the second, “there can be no overall health in the agricultural system if there is ill health in any one domain” (Vieweger and Döring 2015). Figure 1 shows how all the domains are related. In this chapter, the health of the soil and animal domains within organic agriculture will be further explored as well as the many interactions between them.

Soil Health

The main agricultural functions of soil, food production and the promotion of a healthy environment, are both dependent on soil health (Doran and Zeiss 2000). It is helpful to be aware of the current status of soil to understand what areas could be improved in a system. Doran and Zeiss (2000 p. 5-6) presented five indicators of soil health and quality to help quantify soil health which are summarized in the following points.

(I) The indicators should be sensitive enough to respond to changes within the environment without being overly sensitive where short-term weather would affect them.

(II) Such indicators should show positive functions of the soil which benefit humans.

(III) Indicators should help to explain why or why not the soil will be productive.

(IV) These indicators should be accessible to the managers of the land as they are the determining factors of the health and quality of the soil.

(V) Indicators should be inexpensive and easy to use.

Soil organisms have been posited as good indicators of soil health and quality as they fit into all five of the indicator guidelines (Doran and Zeiss 2000). Soil microbial organisms can be beneficial or detrimental to the health and quality of the soil as well as the other domains. These microbes link to the other domains since they can be transmitted from the soil to plants, from plants to animals, and subsequently to humans which can be seen in Figure 1 (Vieweger and Döring 2015).

Interviews of Farmers

In an article by Romig et al. (1995), farmers were interviewed on their assessments of soil health and quality. According to the farmers, soil health is reflected through animals, crops, and water, while soil quality is reflected through crop yield (Romig et al. 1995). One farmer stated, “a healthy plant is a healthy cow is a healthy milk cheque” (Romig et al. 1995 ), suggesting that farmers believe soil health and quality are related to production. The farmers went on to say that, “loose, soft, crumbly, flexible, mellow, darkly coloured, and loamy” soil is healthy soil with the presence of earthworms, natural earthy scents and lack of crusting or compaction (Romig et al. 1995 ). They classified unhealthy soil as “massive, lumpy, or powdery; having a greasy or rough feel; being dense or solid; lightly coloured; and too light or too heavy in texture” (Romig et al. 1995). They also said that unhealthy soil has a bad/chemical scent and is crusty (Romig et al. 1995). Another farmer said, “If you have a lot of worms in a soil, you know you have a good soil. In an unhealthy soil, you start losing all your microbes that help break down organic matter” (Romig et al. 1995). This article showed that observations based on the senses are the most common way farmers judge soils (Romig et al.1995).

Animal Health

Animal health is much less studied compared to soil health and those studies that have been conducted focus largely on the health effects on the consumer. Although there is a lack of research, the current strategies of animal health in line with One Health principles and organic agriculture aim to understand why a disease is present in a situation so that preventative measures can be put in place (Nicourt et al. 2014). As one disease may not be independent of another, it is also logical to study multiple diseases at once (Nicourt et al. 2014). Pathogens present on the farm have their state of equilibrium, similar to soil microbes (Nicourt et al. 2014). This state of equilibrium could be destroyed with the introduction of new pathogens and cause many illnesses and diseases in the animals (Nicourt et al. 2014). Understanding this equilibrium concept aids in the maintenance of good animal health (Nicourt et al. 2014).

Interaction Between Soil and Animals

Understanding how animals interact with the soil is beneficial for understanding different risks to humans (Vieweger and Döring 2015). When soils are healthy, animals raised on those soils are also healthy, have lower occurrences of diseases and have improved production rates (Romig et al. 1995), all of which are important to success in organic agriculture. Exposing animals to poor soil conditions and a poor environment can lead to an imbalance within the animal and cause sickness or disease (Van Bruggen et al. 2019). By expanding microbiomes within soils, the microbiome of animals will also expand (Van Bruggen et al. 2019). This expansion in soils and animals has been shown to reduce infections, illnesses, and diseases (Van Bruggen et al. 2019). Soils rich in beneficial microbes produce feeds with higher levels of those beneficial nutrients which are then transferred to the guts of animals when consumed (Van Bruggen et al. 2019). These beneficial microbes also help to strengthen animal immune systems and fight off detrimental pathogens (Van Bruggen et al. 2019). As stated in the Animal Health section, each agricultural system has its own equilibrium of pathogens and beneficial microbes. The introduction of new organisms to the soil would create disequilibrium and potentially create a cascade of diseases or illnesses to occur affecting the animal feed, grazing land and animal health (Nicourt et al. 2014).

Case Study

In a study by Massaccesi et al. (2019), geese were reared in vineyards to examine the effects of the soil on the geese and vice versa. This study showed a positive correlation between animal health and soil health, making it an interesting study for those who fear overgrazing as a problem in agricultural systems with animals integrated into perennial crops. When overgrazing can be avoided, integrating animals with perennial crops promotes lower land use for housing and feeding. The controlled grazing associated with this integration also leads to improved animal production and health. To limit the need for fertilizers, farmers can use the excreta of the animal, in this case, the geese, that were reared on the land. These managed droppings provide trace elements, organic matter, and macronutrients. These elements support soil microbe communities and provide nutrients for the crops, in this case, grapes. Another common benefit of integrated animals shown in this study is the service of weeding provided by the geese. This benefit declines if too many geese are reared at one time and overgrazing occurs, or if too few geese are reared and those geese are unable to keep up with the weeds. In both situations, the overall production of the vineyard is reduced.

In the study, three vineyards were selected: one with high geese density (HGD), another with low geese density (LGD), and the last without geese (WG). For most aspects, the HGD and LGD systems were favoured since they had the most beneficial results in terms of vineyard production and animal production. Overall, the results showed that geese provided beneficial services to the vineyard as they provided useful nutrients and weed management without harming the soil. The geese were also found to lower the content of copper (Cu) in the soils by eating the weeds and grass in the vineyard, but it resulted in an accumulation of Cu in the livers of the geese. This study is a very useful model for using animals on fields as it shows the benefits of the interaction of animals with the soil (Massaccesi et al. 2019).

Conclusion

There are five interconnected domains in agriculture – soil, animals, humans, plants, and ecosystems. To ensure there is balance and good health in one domain, one must make sure that there is good health in all domains. Increasing our understanding of soil and animal health promotes holistic management practices that can be used to help reduce the impacts of organic agriculture. Holistic management is a central goal in organic agriculture and aims to improve soil production and functions, conserve soil resources, and support and maintain soil health and quality. Improving the health of one domain will increase the health in other domains as was shown in the case study of integrating geese into vineyards where production rates of the crops and animals increased, soil conditions improved, and the health of the animals and soil improved. All these aspects demonstrate methods of organic production that increase produce while also improving the sustainability of the soils.

References

Center for Disease Control. 2018. One health basics. Retrieved March 06, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/index.html

Doran JW, Zeiss MR. 2000. Soil health and sustainability: managing the biotic component of soil quality. Applied Soil Ecology 15, 3-11.

Massaccesi L, Cartoni Mancinelli A, Mattioli S, De Feudis M, Castellini C, Dal Bosco A, Marongiu ML, Agnelli A. 2019. Geese reared in vineyard: Soil, grass and animals interaction. Animals: An Open Access Journal from MDPI, 9(4), 1-13.

Nicourt C, Cabaret J. 2014. Animal healthcare strategies in organic and conventional farming. In: Bellon S, Penvern S. (eds) Organic Farming, Prototype for Sustainable Agricultures. p 171-179.

Romig DE, Garylynd MJ, Harris RF, McSweeney K. 1995. How farmers assess soil health and quality. J. Soil and Water Conservation 50(3), 229-236.

Van Bruggen AH, Goss EM, Havelaar A, Van Diepeningen AD, Finckh MR, Morris JG. 2019. One health – cycling of diverse microbial communities as a connecting force for soil, plant, animal, human and ecosystem health. Sci. Total Environment, 664, 927-937.

Vieweger A, Döring TF. 2015. Assessing health in agriculture – towards a common research framework for soils, plants, animals, humans and ecosystems. J. Sci. Food Agric. 95, 438-446.