2 02: MEET PAPALEGBA

MEET PAPALEGBA

![Graphic from Library and Archives Canada Blog, “Treaties with Indigenous peoples: past and present,” by Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour, posted 21 June 2019. Graphic title and creator not specified. Information provided by LAC: On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse; in the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture; on the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://books.lib.uoguelph.ca/app/uploads/sites/61/2021/08/02-blog-banner.jpg)

TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (2015) Calls To Action make explicit the need for all Canadian media programs “to require education for all students on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations” (TRC, 2015, 86).

WHY LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS?

Territory acknowledgements are one small part of disrupting and dismantling colonial structures. For Indigenous peoples, it is a sign of respect to share who you are, who you are connected to and the land that you come from while offering gratitude to the land and people of the territory.

The current practices of acknowledgement by members of the University of Guelph community are signs of respect for the historical and current realities of the land and its Indigenous stewards.

Land acknowledgements are a time to consider our individual and collective roles in building relationships with First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples and our responsibilities to the land. Amongst Canadian settler-scholar communities, land acknowledgments are an emerging ritual for signaling efforts towards decolonization and reconciliation.

I cannot work in this role without recognizing that in our shared history, colonial Canada decided for the necessity of cultural assimilation regardless of costs. My summer 2021 shockingly revealed the tragedies of Canada’s residential school systems. I stand with the Indigenous communities mourning the devastating loss and the intergenerational impact of residential schools. Summer began with heartfelt tears for and with the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and Indigenous communities. Celebrating the rich and diverse cultures of First Nations, Inuit & Métis peoples is a chance to expand our learning and renew our work toward reconciliation.

RESOURCES

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc: Kamloops Indian Residential School Missing Children: <https://tkemlups.ca/kirs/>

Kamloops Indian Residential School: Background: <https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/entities/46>.

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation: <https://nctr.ca/>

Maamaawisiiwin Education Research Centre: <http://www.indigagogy.com/>

Learn about Indigenous Initiatives at University of Guelph, as well as commitments and actions toward reconciliation and decolonization: <http://indigenous.uoguelph.ca>

Reach out to the people working at the Indigenous Student Centre at the University of Guelph: <indigenous.student@uoguelph.ca>.

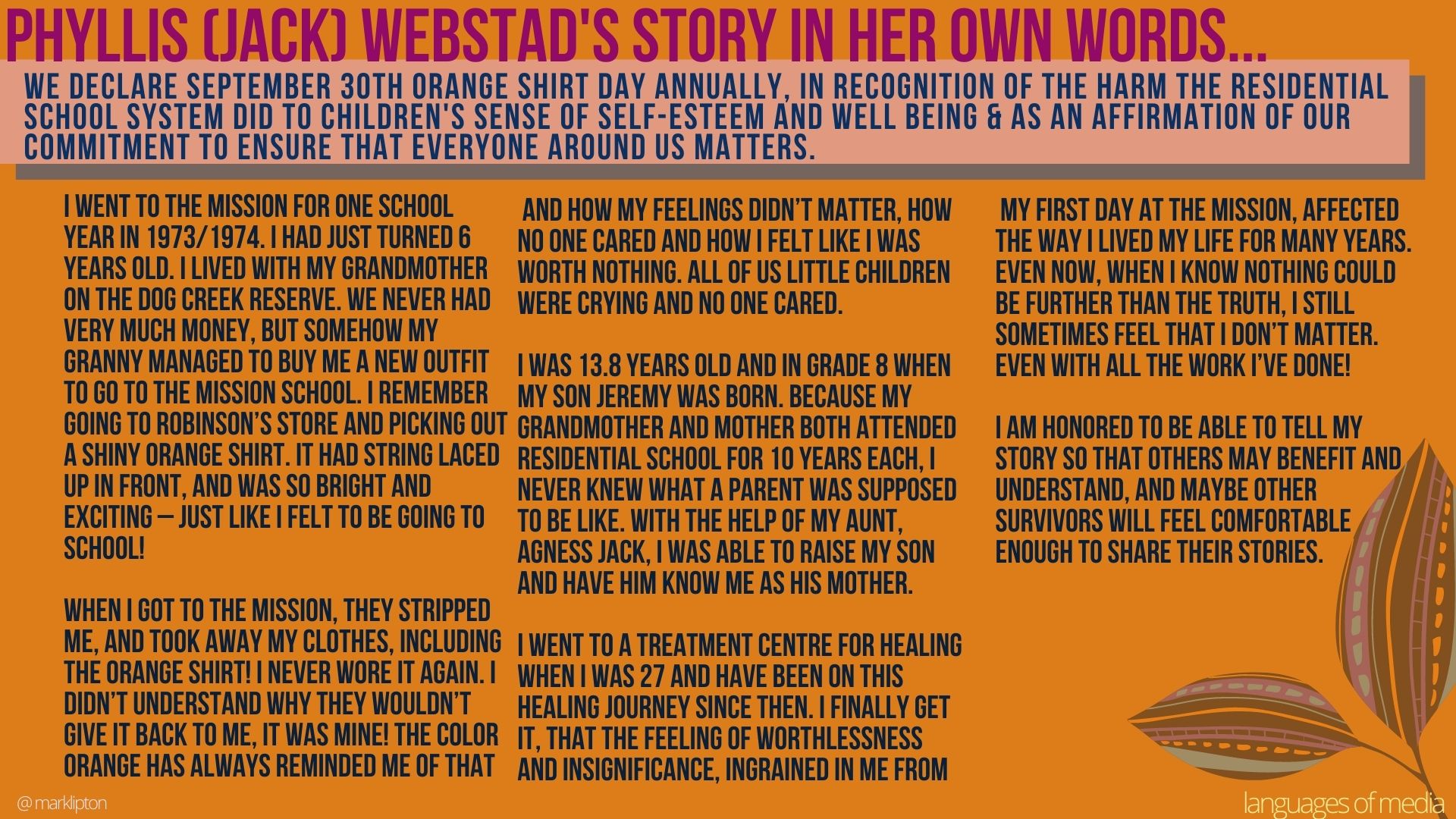

PHYLLIS (JACK) WEBSTAD’S STORY

RESPECT INDIGENEITY

Our reasons for beginning with Indigenous land acknowledgement represents an ongoing commitment to reconciliation, holistic education, and relationship building. These commitments help ground our intentions, work, and action. They also help reinforce our own relationships with others living on shared land and help define what we mean by the word HOME.

READ

Kluttz, Jenalee; Walker, Jude; & Walter, Pierre. Unsettling Allyship, Unlearning and Learning Towards Decolonizing Solidarity. 2020.

Unsettling Allyship, Unlearning and Learning Towards Decolonizing Solidarity

Canada resides on traditional, unceded and/or treaty lands of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. At the University of Guelph, we work on Anishinabewaki ᐊᓂᔑᓈᐯᐗᑭ, Attiwonderonk and Haudenosaunee land, in the territory of the Dish with One Spoon; on Treaty lands and territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit; and we are held to the resolutions of the Between the Lakes Purchase (Treaty 3, 1792).

Personally, I, marklipton, live and work on Anishinabewaki ᐊᓂᔑᓈᐯᐗᑭ, Huron-Wendat and Haudenosaunee land that was part of the Toronto Purchase (Treaty 13, 1805). I recognize the lands of Indigenous peoples locally, across Turtle Island and around the world. As a retreating diasporic outsider & a settler immigrant Jew, I recognize how imperial and colonial constructs shape my social identity, worldviews, and privilege. My family settled on this land three or four generations ago, and I, too, choose to inhabit these spaces and land. This is where I have chosen to call HOME. Nonetheless, I have no birthright.

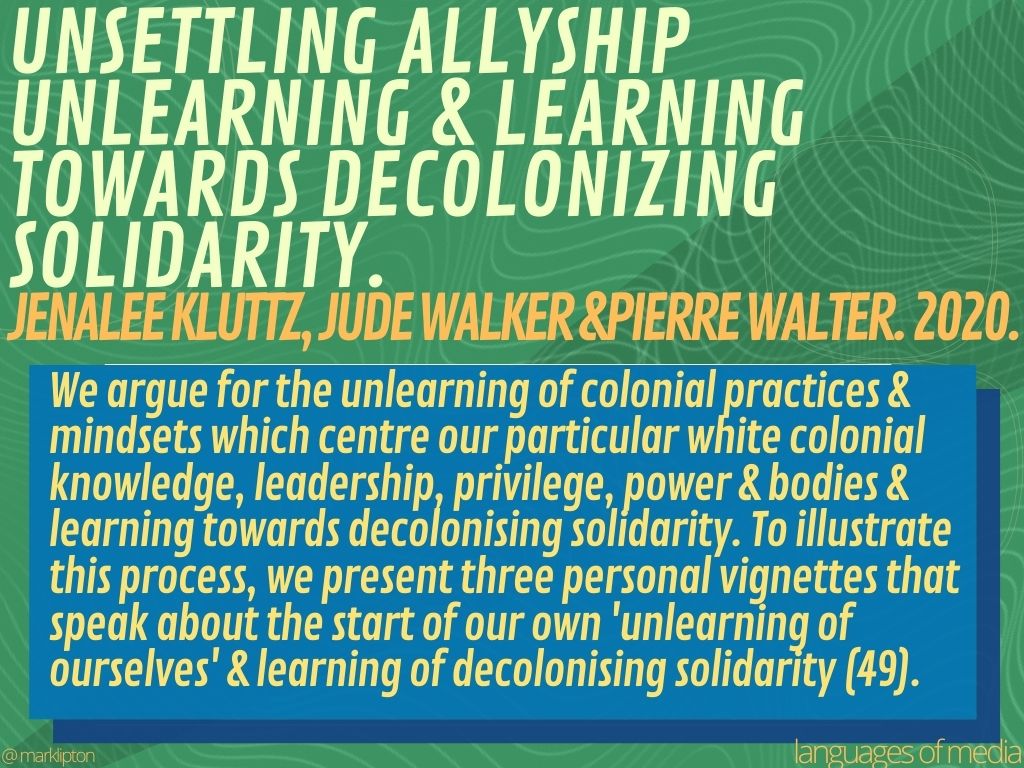

CROSSROADS

I don’t know if anyone has said this to you yet. Welcome to ADULTHOOD. You will get the hang of this! This is a major transition in your life. Let’s agree that there’s no time for hesitation or paralysis. All we have is right now, this moment.

Have you ever found yourself at a crossroads or at an intersection and you hesitated? One who hesitates is lost. I would like to take this opportunity to introduce to you to PAPALEGBA.

![image: PAPALEGBA: mirror images of Baron Samedi, the Haitian Voodoo God of the crossroads. A skeleton wearing a tuxedo and top hat, tips his hat to those who hesitate. Meet PAPALEGBA; in one mirror image, Professor Lipton's face is superimposed over the skull of PAPALEGBA.]](https://books.lib.uoguelph.ca/app/uploads/sites/61/2021/08/image4.jpg)

MEET PAPALEGBA

Have you heard of PAPALEGBA? PAPALEGBA is the Haitian voodoo god of the crossroads.

PAPALEGBA is neither good nor bad. PAPALEGBA stands at the crossroads —stands at the intersections of life, directing traffic. Who do you think helps with DIRECTING ALL THOSE decision makers as they move throughout life? PAPALEGBA —this isn’t about good or bad, bad nor good.

PAPALEGBA makes sure that life keeps moving. If you delay; if you hesitate; if you cannot decide; he will decide for you. PAPALEGBA will make your choice.

You are about to start making a great number of decisions. About your day, about your life. In fact, every moment is made up of a series of decisions. You will need to apply self-regulation skills to activate your pre-frontal medial cortex or that part of your brain in charge of your executive functions. This is your control mechanism. Your conscious thought is necessary if you want your decisions to be in line with your values.

The point of PAPALEGBA is: You cannot delay. You cannot equivocate. Equivocation is not an option. Life is not about to be or not to be. LIFE is right now. It’s about being, about actively living. About living in the moment and about recognizing that the next movement is about to come, and life is about actively choosing your life and making your world. The way that we can actively choose our life so that we can achieve our goals is to recognize we are actively making or designing decisions. Decision making!

Let me ask you a question that’s on my mind. Maybe write your answer on a little piece of paper.

QUESTIONS

What is your DREAM JOB? Do you have a dream job? Do you have a dream? Something that excites you. That burns inside of you.

Whether you answer yes or no —it’s your process of decision making that helps you actively work toward your goals. We seek to design decision making so that our choices are informed and supported by our values and integrity.

We live in a world where media messages are so heavily controlled, we don’t see how media has a grasp on our lives, our senses of self, on our symbols systems, and our processes of making meaning.

I know there is hope. There are strategies and tactics of resistance. Change is possible.

To begin, we must first pay ATTENTION. One of the first steps in living a life of integrity is to be mindfully making decisions.

WHAT IS HOME?

You land acknowledgement represents an ongoing commitment to reconciliation, holistic education, and relationship building. These commitments help ground your intentions, work, and action. They also help reinforce your own relationships with others living on shared land and help define what you mean by the word HOME.

Where is your home? Does your sense of HOME resist or reinforce colonialization? As you explore matters associated with Indigeneity and decolonization, I challenge you to consider your own perspectives, ideas, and norms.

How might an online course carve out a respectful identity–as a collective with a unique positionality? How might you offer gratitude for the land? How might you offer gratitude to the Indigenous communities and their stewardship—past, present, future?

REFLECT ON YOUR LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Preparing a land acknowledgement is an ongoing and reflective process. To begin, as a member of today’s society, I hope your journey toward Indigenous respect and understanding is an open and reflective process. To begin this journey, I suggest you adjust your point of view so you can come in peace. Aim to learn about and celebrate Indigenous histories and worldviews. Recognize that each First Nation possesses both shared and individual heritage and culture, languages, and systems of governance. To this end, I support Indigenous governance education; Indigenous history, culture, and the journey towards self-determination are core competencies that promote positive relationships among all citizens.

.

RESOURCES

Native Land Digital is Indigenous-led organization initiating discussions of colonization, land rights, language, and Indigenous history. The Native Land tool maps Indigenous territories, treaties, and languages. This tool is not meant to be an official, legal, or archival resource; it is a crowdsourced body of research meant to encourage education and engagement on topics of Indigenous land. Available at: <https://native-land.ca/>

Similarly, Whose Land is a web-based application that uses GIS technology to assist users in identifying Indigenous Nations, territories, and Indigenous communities across Canada. Whose Land collects six different maps of Indigenous territories, Treaties, and First Nations, Inuit, and Metis communities. Whose Land worked in partnership with Native-Land, building on existing data with research that identified gaps forming an improved data set that both share openly. Available at: <https://www.whose.land/fr/>

|

These maps are fluid and ever changing. Nonetheless, these maps can help create dialogue around reconciliation. |

These are fun and interactive resources. Look up your HOME address on https://native-land.ca/ and PLAY around with its features. What strikes you? What is your relationship to this territory? How did you come to be here?

What are the difficulties when it comes to mapping Indigenous territories? How does the modern idea of a ‘nation-state’ relate to Indigenous nations? Who defines national boundaries, and who defines a nation? Is it possible to imagine territory or nation outside a colonial framework?

What are some of the significant differences and similarities of these two cartographic resources? Are these maps useful, or do they contribute to colonial ways of thinking about Indigenous people? How can cartography function as a form of political resistance and self-determination?

In what ways might today’s

digital mapping tools

resist or reinforce

the authority to define land?

What do you know about the history of this territory? How easily can you identify some of the obvious impacts of colonialism? Are there other ways for you to disrupt and dismantle colonialism beyond this territory acknowledgement?

Write out the names of two Indigenous nations and learn how to pronounce them properly. Know which treaty agreement covers your HOME. PLAY with native-land.ca and write for ten minutes: “your understanding of what is at stake.” Write out a LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT that feels right for you. Practice saying your acknowledgement on camera.

I HAVE NO BIRTHRIGHT

There is little question that many of us benefit from colonial structures. Attending to settler colonialism requires a significant departure from traditionally understood approaches to teaching and learning. In my experiences, these past methods and conventions assumed inclusion of all identities, all bodies, and all learners. Media studies (for me, from the moment I began the commitment to ongoing learning and higher education) works to include all people who are gendered and address concerns of all ethnic groups including Indigenous peoples.

I was taught to think about myself (and my Self) in relation to a gendered and racialized society. I was also taught how to move toward social change for good and techniques for meaningful social action. However, (after thirty++ years) directly engaging settler colonialism with my pedagogical philosophy involves additional frameworks; our priorities shift when equity, diversity and inclusion are prioritized.

My teachings always aim to unmask gender and race as social constructions; my work in media studies exposes myths about gender, race, and class –highlighting structural and inherent misogyny, racism, and unequal power relations.

Yet, within this important work, a consideration of Indigenous peoples remains rooted in understanding colonialism as an historical point in time, away from today’s modern society.

I experienced a significant perceptual hitch when I realized that more Indigenous children are currently living in foster care than the sum of children forced into residential schools—as far as we know.

Indian residential schools [death camps] operated in Canada between the 1870s and the 1990s. The last school closed in 1996. Indigenous children in Ontario under age 15 represent 4.1% of the population; they also represent about 30% of all Ontario foster children. Looking at the entire nation, 52.2% of children in foster care are Indigenous yet account for only 7.7% of the child population (according to Census 2016).

Twenty-eight thousand, six hundred and sixty-five (28 665) Canadian foster children under the age of 15 who live in private homes, fourteen thousand, nine hundred and seventy (14 970) of these foster children are Indigenous (according to Census 2016).

In Canada, 38% of Indigenous children live in poverty compared to 7% of other children who are non-Indigenous (National Household Survey 2011). For Canadian Indigenous people – quality of life is getting worse.

Navigating settler colonialism within my teaching and learning bashes and exposes the formidable, still-existing, often invisible structures that impact Indigenous peoples and others. I explore practical applications of decolonization in my learning environments (and my everyday HOME life).

I also accept the complexity of grappling in and against settler colonialism as well as the physical and emotional challenge of maintaining energy and efforts in this struggle. My pedagogical approaches target radical transformations; changing structures of higher education is possible and desirable. In the end, decolonizing our professional and personal worlds is but a first step toward radical global change, for the sake of Nature and all sentient life.

All students are encouraged to build respectful relationships with First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples and communities. A fundamental part of decolonization requires deep listening practices, an openness to learning and a regular self-reflection practice. We all have an active role in reconciliation.

The Indigenous Student Centre is a resource for students <indigenous.student@uoguelph.ca>.

![image: Today in Canada, more Indigenous children live in foster care than the sum of children forced into residential schools. Indian residential schools [death camps] operated in Canada between the 1870s and the 1990s; the last school closed in 1996. Indigenous children in Ontario under age 15 represent 4.1% of the population; they also represent about 30% of all Ontario foster children. In Canada, 52.2% of children in foster care are Indigenous yet account for only 7.7% of the child population (Canadian Census 2016). 38% of Indigenous children live in poverty compared to 7% of other children who are non-Indigenous (National Household Survey 2011).](https://books.lib.uoguelph.ca/app/uploads/sites/61/2021/08/image6-2.jpeg)

Indigenous people’s quality of life is getting worse. Let’s look at the numbers:

28 665 total foster kids

14 970 Indigenous foster kids

13,695 foster kids who are not Indigenous

Twenty-eight thousand, six hundred & sixty-five (28 665) foster children under the age of 15 live in private homes; fourteen thousand, nine hundred & seventy (14 970) of these foster children are Indigenous (Canadian Census 2016).

Navigating settler colonialism within teaching & learning bashes & exposes the formidable, still-existing, often invisible structures that impact Indigenous peoples and others.]

CARTOGRAPHY & HOME

Maps function as colonial artifacts and represent a very particular way of seeing the world – a way primarily concerned with ownership, exclusivity, and power relations. By mapping a territory, it is made known, quantifiable, and controllable in a way that reflects the interests, purposes, and perceptions of those who created the map. Usually (& historically), any interest in mapping and maps reflects territorial chaos and disorder, where a dispute over uncertain ownership requires resolution. Of course, this is perhaps one of the more obvious examples of colonial power, which extends the function of mapping as a tool for land appropriation in the name of military security resulting in ongoing economic dominance through taxation and resource exploitation.

| In what ways might today’s digital mapping tools resist or reinforce the authority to define land? |

In contrast to colonial cartographies, Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada applies Indigenous systems of knowledge and methods of data gathering to decolonize and reterritorialize Indigenous Canada. Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada is a one-of-a-kind map designed to preserve the cultural significance of First Nations, Métis & Inuit communities of Canada by displaying landmarks, points of interest and areas of Canada in the native languages of said groups with accompanying English translations. The place names in this map are the intellectual and cultural property of the First Nation, Métis, and Inuit communities on whose territories they are located.

![image: If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together. –Lilla Watson, (Australian) Indigenous Murri Gangulu, artist, activist and academic.]](https://books.lib.uoguelph.ca/app/uploads/sites/61/2021/08/image7.jpeg)

COMING HOME TO INDIGENOUS PLACE NAMES

Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada is a cartography project led by Margaret Pearce. Margaret Pearce is enrolled in the Citizen Band Potawatomi and is a cartographer based in Rockland, Maine. She holds a PhD in Geography from Clark University, where she focused on map history and cartographic design. Dr. Pearce is a faculty associate and Associate Professor in the department of Geography, at the University of Kansas. She also teaches in the Indigenous Studies Program.

![image: Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada, excerpt from interview with Margaret Pearce. 5 Questions on Data and Indigenous Place Names, interview with Catherine D’Ignazio. Margaret Pearce is enrolled Citizen Band Potawatomi & a cartographer based in Rockland, Maine. She holds a PhD in Geography from Clark University, where she focused on map history & cartographic design. Dr. Pearce is a faculty associate and Associate Professor in the department of Geography at the University of Kansas. She also teaches in the Indigenous Studies Program. Dr. Pearce's (2017) map Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada is a one-of-a-kind map designed to preserve the cultural significance of First Nations, Métis & Inuit communities of Canada by displaying landmarks, points of interest and areas of Canada. I really appreciated the attention you gave to how people “exercised their right to silence about the names.” Can you tell me about a conversation where someone explained why they didn’t share a particular name or piece of information with you? Margaret Pearce: Nobody volunteered reasons for not including information. Nobody explained. I would ask, “On your terms, would you be interested in sharing? And it would be on whatever terms are acceptable to you.” So they chose the terms and chose what they wanted to give me and what it would look like. And how extensive it would be. And that was it. But I did blunder early on, by asking someone for what I called “missing parts.” I remember this vividly because I have so much shame about it. He had submitted some names without translations and in the beginning of the project I was really focused on translations because that’s where — to me as a nonspeaker — all the meaning comes forward. I said, “Thank you so much. Would it be possible, if you have more time, to also submit some of the missing parts?” He didn’t respond. As I looked at my email where I had written, “where are the missing parts?” I slowly realized my mistake. It was a really powerful lesson. I emailed & apologized, “I’m so sorry that I wrote that & I understand.” That lesson really changed everything. When things aren’t shared, it’s because it’s none of our business. I should have known better, but I don’t always remember I know better. Everybody is different. And so whatever it’s going to be, I just work with whatever they want to share. I tried to express that in the writing on the map where I say: these are some of the names; these are some of the Nations. And it’s not everything.]](https://books.lib.uoguelph.ca/app/uploads/sites/61/2021/08/image8-2.jpeg)

RESOURCE

Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada map full size secure.pdf

This map may be printed for personal or educational use only. © 2017 Canadian American Center, University of Maine. Available at: <https://umaine.edu/canam/publications/coming-home-map/coming-home-indigenous-place-names-canada-pdf-download/>.

OPPORTUNITIES + CHALLENGES

There is great value in the ability to increase your self-awareness and to identify your strengths and weaknesses. These abilities allow you to approach tasks and challenges with a better understanding of how to succeed and when to watch out for potential pitfalls. Also, with increased self-awareness and clear sets of strengths, you can effectively communicate what you can contribute, which is essential for things like job interviews. You may have made lists to help guide and design your decision making —asking what are the pros; what are the cons? You may have heard of a SWOC analysis —what are the strengths? Weaknesses? Opportunities? Challenges? This is a system for assessing choice and for considering the outcomes of your choices.

Of course, you don’t need to do a SWOC analysis a billion times a day for each decision. And you need to know when you must step back and slow down and design a system for your decision making so you can actively create your world. That’s what I mean by DECISIONS-BY-DESIGN.

Consider this: When you aren’t designing your own decision-making processes; when you aren’t actively making a choice; you are both: (1) living in a sea of unconscious processing guided by your reptilian brain, your primitive brain; & (2) you are letting someone else make choices for you.

|

IF YOU DON’T SPEAK UP, SOMEONE WILL SPEAK FOR YOU. |

Don’t let PAPALEGBA take responsibility for your life.

You must accept and live with the consequences of all your actions. All decisions come with outcomes, consequences, and effects. You know what choices are difficult.

Don’t let PAPALEGBA interfere as you enter the crossroads, this transition of your life, transition into adulthood. Make your decisions by design. Weigh the pros and cons; consider the strengths weaknesses opportunities and challenges. Every moment is filled with thousands of choices.

You know when something stirs inside you, when your body sends you a private message, like goosebumps or shivers or a pain in the pit of your gut. You know when there is something: an issue, a project, a moment, that you really care about. Something that makes you want to take ACTION!

Don’t let someone else speak for you. Don’t let someone else decide for you.

Speak or be spoken for.

Decide or live with the untold consequences of someone else’s decisions. Some decisions have a lasting effect and sadly, we don’t know (for the most part), when we are making unwise decisions.

Remember if you enter the crossroads without knowing where you are going, PAPALEGBA will make the decision for you. It might be magical. It might be hellish. We don’t know. However, I do believe that regardless of what drives your decision –even when someone else decides for you –YOU must still take responsibility for the outcomes, implications, and results of each of your choices.

Adulthood comes with responsibility. Mindful, conscious decision making ensures you will make fewer errors of judgment. Don’t let PAPALEGBA get in your way.

| Don’t let PAPALEGBA take responsibility for your life. |

SLOW

How can you practice SLOW THOUGHT?

How quickly do you move through the world?

What is your pace of life?

Do you want/need to SLOW down?

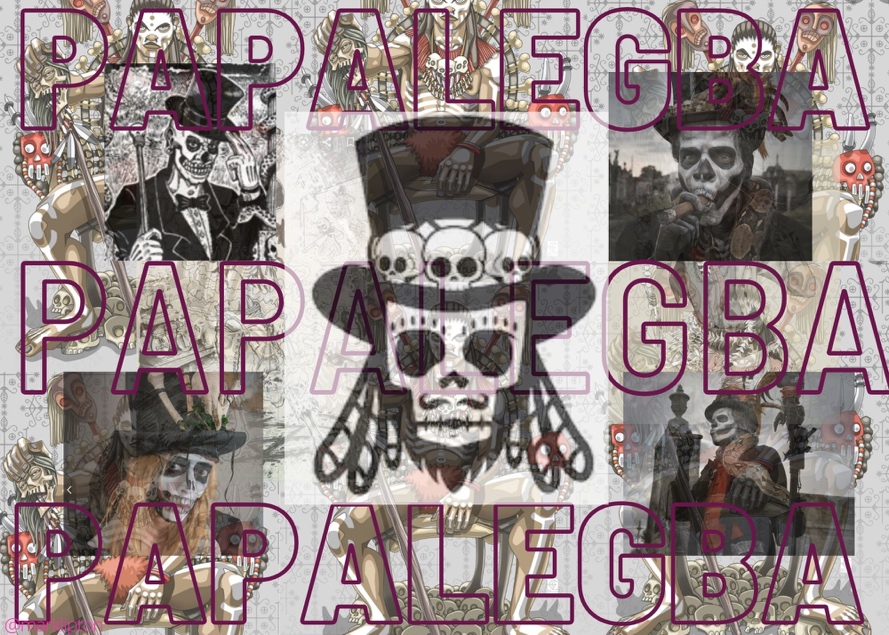

SLOW THOUGHT: A MANIFESTO

Imagine if you dedicated part of every day to (what they call) non-doing; imagine if your life was led by a sense of non-striving, setting aside all your determined efforts and ruthless ambition.

How do you think this subversive attitude and value could impact your life?

The lives of your family?

The rest of the world?

|

Slow thought is marked by peripatetic Socratic walks, the face-to-face encounter of Levinas & Bakhtin’s dialogic conversations |

HOW DO YOU PRACTICE SLOW THOUGHT?

When I wonder . . . the world seems to move at a different pace. I wonder why? To wonder, to think, to contemplate . . .these are the behaviours you will need if you want to really make a difference in the world. How can you avoid the temptations of consumerism? How can you recognize the manipulative means and insidious messages of media and other big corporations? Think about it.

| CONTEMPLATION requires SLOW THOUGHT |

LEARNING IS RELATIONAL

Let’s work through the challenges of learning together. Slowly. There is no rush to the finish line—’cause let’s face it: the finish line = death. What’s your rush? Complex thought take time. Complex thought is highly unlikely with no written text. THAT’S WHY Pros/Cons lists or SWOC analyses are useful for making difficult decisions. If you are ever to think consistently or coherently for long, I recommend you engage (in fact you need) another person as a partner in dialogue.

Life is sometimes better with a good friend.

As you engage in the work required for our course, I encourage you to interact with another person or other people. I hope you connect with and share these materials and your work with lots of people. Maybe you’ll talk to the same person each week, or a different person. Copresence is not required; you can talk on phone or video chat. However, a SLOW conversation is suggested. How do you see the world? How do your friends?

CONTEMPLATE REALITY: THREE Points of view

I have found this model to be a very useful distinction for avoiding misunderstandings. Perhaps we have very different philosophies of reality. Consider these three ways of looking at the world. There are:

REALISTS or RATIONALISTS

TRANSACTIONALISTS &

RELATIVISTS

REALIST or RATIONALIST

These folks claim to see the world as it really is; reality is out there and is completely knowable and observable. For the realist, our job is to discover reality as it really is.

TRANSACTIONALIST

These people claim to experience the world according to one’s perception of it. There is no world to be perceived as it really is because these people know that reality is only partially knowable. For the transactionalist, our job is to make our perception match reality as much as possible.

RELATIVIST

These friends insist that nothing exists. Everything, and they mean everything, is a manifestation of our minds. There is no reality, or they believe that reality is completely unknowable. Reality is totally made up by humans, and always relative to humans.

METAPHOR OF THREE UMPIRES

What do they have to say about balls & strikes? How might these three points of view help frame your sense of the world? Are you a transactionalist, like me? Or do you see things differently? I wonder.

![image: Norman Rockwell's (1948) Tough Call (also called Game Called Because of Rain, Bottom of the Sixth, or The Three Umpires]. The painting by American artist Norman Rockwell, painted for the April 23, 1949, cover of The Saturday Evening Post magazine. Oil on canvas; dimensions: 109 cm × 104 cm (43 in × 41 in); Source (WP: NFCC#4). Non-free use rationale: |image has rationale=yes]](https://books.lib.uoguelph.ca/app/uploads/sites/61/2021/08/image11.png)

|

REALIST/RATIONALIST: I CALLS ‘EM THE WAY THEY ARE TRANSACTIONALIST: I CALLS ‘EM THE WAY I SEES ‘EM RELATIVIST: THEY AIN’T NOTHING UNTIL I CALLS ‘EM |

MEANING AND RELATIONSHIPS

I believe there is a knowable, observable world out there—but I don’t believe I can ever know it as it “really is,” rather, only as I perceive it. My perceptions are limited by my senses & my mind; and the human mind is both conditioned and limited by our language. In my philosophy, meaning making involves RELATIONSHIPS.

| MEANING like LEARNING is RELATIONAL. |

My point of view is TRANSACTIONALIST; by this, I want to emphasize how meaning arises from TRANSACTIONS. I say TRANS and not interaction because in this relationship there are three elements:

1. a meaning maker (respondent, creature making meaning, me, or you);

2. a sign: the thing used to make meaning; &

3. a referent: object referred to by sign and its mental concepts.

By mental concepts, I refer to those reactions and responses that are called up in the mind of the respondent, that is, the sounds and words for which the sign stands.

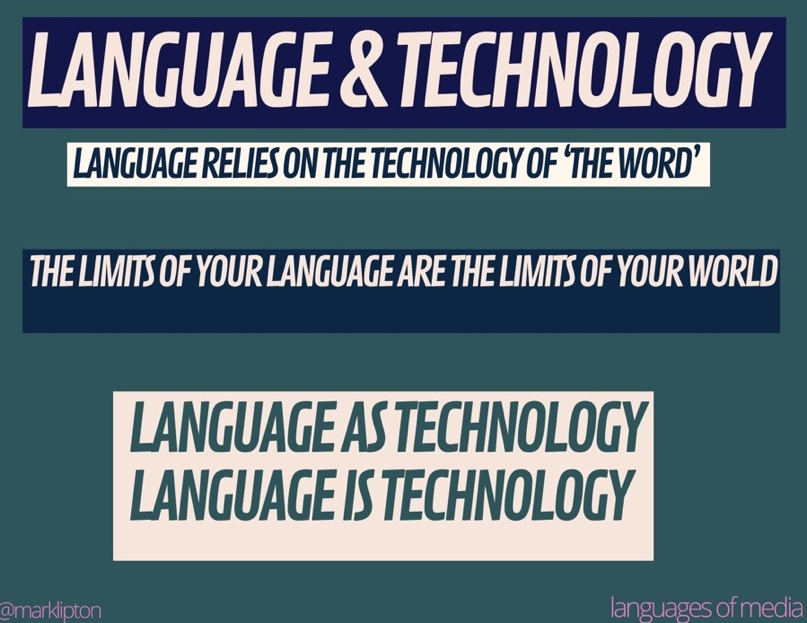

TRANSACTIONALISM: Fundamental Premises

VER·I·SI·MIL·I·TUDE: THE APPEARANCE OF BEING TRUE OR REAL.

To oppose Aristotle’s THREE laws of logic requires our thinking to reimagine how these propositional statements can be reframed so that we can see through the manipulative mean and ideological implications of powerful media messages. To this, I am guided by and

prefer a different set of principles. Though not exactly opposite to each of Aristotle’s laws, the principles of General Semantics are more in line with scientific thinking and help differentiate between the real world and symbolic forms with great verisimilitude. [e.g., the picture of the sunset is not the same as the real sunset.] By recognizing that classifications are human-made and not natural, TRANSACTIONALIST Alfred Korzybski (fonder of General Semantics) designed THREE non-Aristotelian laws to better reflect the characteristics of reality.

1. NON-IDENTITY: A IS NOT A

2. NON-ALLNESS: A IS NOT ALL A

3. SELF-REFLEXIVENESS: ABSTRACTS OF ABSTRACTS OF ABSTRACTS

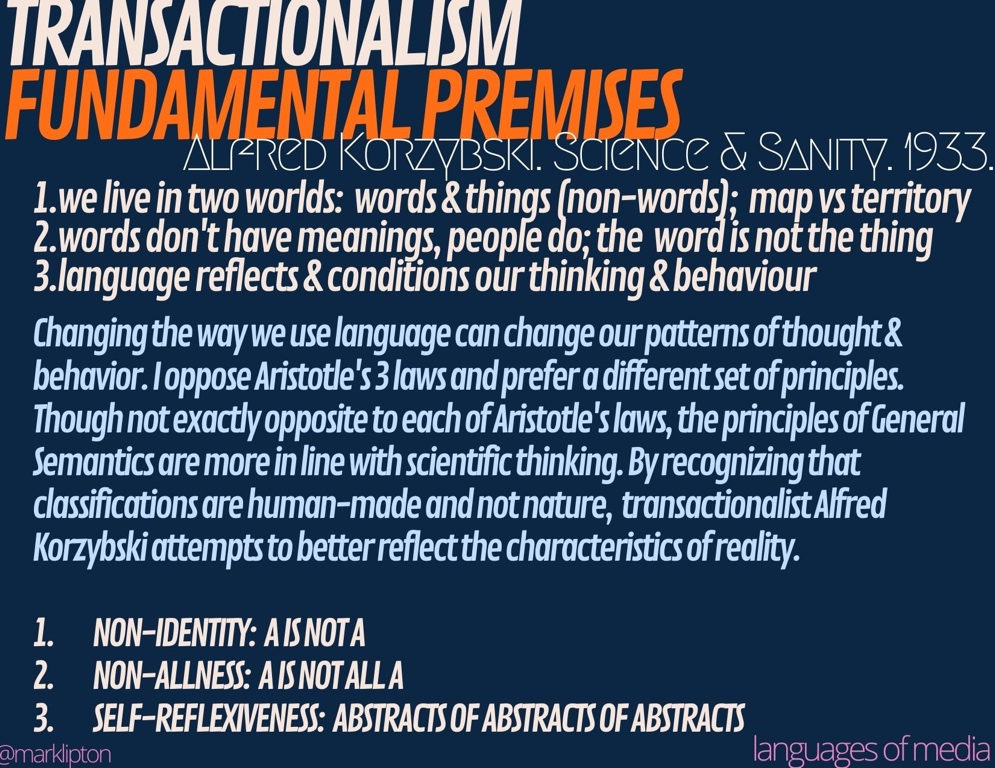

TRANSACTIONALISM: THREE NON-ARISTOTELIAN LAWS

1. NON-IDENTITY: A IS NOT A

The word or symbol is not the thing. People act as if words were things (we all do this). It’s a kind of word/symbol magic leading humans to mistake symbols for referents.

i. vertical non-identity: Smith1 is not Smith2

ii. horizontal non-identity: Smith yesterday is not Smith today

Techniques for reminding us of non-identity:

1. indexing (vertical non-identity) & 2. dating (horizontal non-identity).

2. NON-ALLNESS: A IS NOT ALL A

You can’t say everything about anything. Something is always left out when we abstract, even at lowest levels of abstraction, we can only perceive part of “reality.”

|

THE MAP IS NOT THE TERRITORY |

Technique for reminding us of non-allness: ETC, that is, we can always add more.

3. SELF-REFLEXIVENESS: ABSTRACTS OF ABSTRACTS OF ABSTRACTS

You can’t say everything about anything. You can always abstract to another higher level, infinitely. There is always more to say. Technique for reminding us of self-reflexiveness: ETC, that is, we can always add more and abstract higher.

|

CONTEMPLATION requires SLOW THOUGHT. LEARNING is RELATIONAL MEANING IS RELATIONAL |

QUESTIONS

What do you understand about the interrelated meanings of these three statements?

What does it mean to insist learning is relational?

What does it mean to insist meaning is relational?

Who are your people? Who is your person?

How do these people impact your senses of learning?

Your sense of meaning?

![image: All Learning is a process of association. All learning is relational. All learning connects signs and experience.]](https://books.lib.uoguelph.ca/app/uploads/sites/61/2021/08/image15-2.jpeg)

INDIGENOUS PLACE NAMES IN CANADA

In Canada close to 30 000 official place names are of Indigenous origin, and efforts are ongoing to restore traditional names to reflect Indigenous culture. As the original occupants of the land now known as Canada, Indigenous Peoples named the land and the features around them. As Europeans settled in Canada, they introduced names to reflect their own culture and history. Indigenous heritage is reflected in many place names where European settlers tried to transpose the sounds of the words they were hearing into either English or French. Today, efforts are underway to restore traditional names to reflect the Indigenous culture wherever possible.

TOWARDS RECONCILIATION

Exploring <Stories from the Land: Indigenous Place Names In Canada> offers a lens to discover and understand the languages, histories, and cultural identities of Indigenous peoples. Exploration of these names provides insight into the Indigenous histories, lived experiences, and is a step towards a reconciliatory future.

GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES BOARD OF CANADA

The naming of places is a cultural phenomenon dating back to the earliest of human history. Assigning names to places is a practice that serves many purposes. Indigenous place names reinforce an intimate relationship with the land, convey a broad range of knowledge such as travel routes and traditional hunting and fishing grounds, and are touchstones for history and legends. They also embody and honour the teachings of Elders and are a tool for educating young people and future generations.

Geographical naming is a continuous work in progress. Place names are not static, and landscapes evolve. Over time, as additional Indigenous place names are adopted across Canada, the GNBC will update its public map, <Stories from the Land: Indigenous Place Names in Canada>.

See: <https://maps.canada.ca/journal/content-en.html?lang=en&appid=0e585399e9474ccf932104a239d90652&appidalt=11756f2e3c454acdb214f950cf1e2f7d>.

DIVERSITY OF INDIGENOUS PLACE NAMES IN CANADA

In 2016, there were:

23 303 confirmed Indigenous names

6272 probable Indigenous names

84 Indigenous languages or dialects represented in these names

PRESERVING AND STRENGTHENING INDIGENOUS CULTURE

Indigenous place names contribute to the preservation, revitalization and strengthening of Indigenous histories, languages, and cultures. In recent years, the Geographical Names Board of Canada has worked with Indigenous groups to restore traditional place names to reflect the culture of the original inhabitants of the territory. Some names of European origin have been replaced by traditional Indigenous names, and some unnamed physical features and populated places have been given names in Indigenous languages.

Each jurisdiction’s approach is different, reflecting its geography, history, and circumstances. This long-term work continues and evolves to represent the coexistence of all cultures from the land’s history.

ADOPTION OF TRADITIONAL INDIGENOUS PLACE NAMES

Hundreds of geographical names are adopted or changed in Canada each year. Here are some examples of Indigenous names recently adopted by the Geographical Names Board of Canada:

In 2015, the Northwest Territories approved five names for the Mackenzie River in the language of the people who live along Canada’s longest river system:

Dehcho (South Slavey language) <http://www4.rncan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/LCBIH>.

Deho (North Slavey) <http://www4.rncan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/LCBXP>.

Grande Rivière (Michif) <http://www4.rncan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/LCBIL>.

Kuukpak (Inuvialuktun) <http://www4.rncan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/LCBIK>.

Nagwichoonjik (Gwich’in) <http://www4.rncan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/LCBIJ>.

In 2016, Manitoba approved 117 Indigenous place names, including Weenipagamiksaguygun, the traditional Anishinaabe name used by the Poplar River First Nation for Lake Winnipeg. <http://www4.nrcan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/GBXYL>.

In 2017, Nunavut approved 625 names in Inuktitut in the Cape Dorset area, including Tatsiumajukallak (ᑕᑦᓯᐅᒪᔪᑲᓪᓚᒃ) and Killapaarutait (ᑭᓪᓚᐹᕈᑕᐃᑦ).

Tatsiumajukallak: <http://www4.nrcan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique?id=OECOI&snrc=&q=&category=O&province%5B%5D=46>.

Killapaarutait: <http://www4.nrcan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique?id=OECFM&snrc=&q=%E1%91%95%E1%91%A6%E1%93%AF%E1%90%85%E1%92%AA%E1%94%AA%E1%91%B2%E1%93%AA%E1%93%9A%E1%92%83&category=O&province%5B%5D=62>.

In 2018, Pimachiowin Aki, on the border of Manitoba and Ontario, was designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO and Parks Canada. Pimachiowin Aki is Anishinaabemowin for the land that gives life. <http://www4.nrcan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/FOBNG>.

Also in 2018, Saskatchewan changed a derogatory name to kikiskitotawânawak iskwêwak Lakes, which is Cree meaning, we remember the women lake. <http://www4.nrcan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/HBBDH>.

In 2019, the Northwest Territories changed the name of the settlement of Detah to Dettah, to reflect the proper spelling recognized by the Yellowknife’s Dene First Nation. <http://www4.nrcan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/LDAWW>.

In 2020, Yukon changed the name of Mount Higgins to the traditional Tetlit Gwich’in name of Jùuk’an. <http://www4.nrcan.gc.ca/search-place-names/unique/KBBIV>.

Nunavut changed the names of the communities Hall Beach and Cape Dorset to their traditional Inuktitut names of Sanirajak and Kinngait. <https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/earth-sciences/geography/indigenous-place-names/19739>.

MAPPING CHANGE

Parks Canada acknowledges a historical disjunct between Indigenous Peoples and the dozens of protected areas they manage. Since the 1800s, Parks Canada has had a long history of excluding and displacing Indigenous Peoples from living on and hunting/gathering within national parks under the guise of conservation.

In growing recognition of this injustice, Parks Canada is working to reconcile wildlife monitoring, tourism, and public relations with the nations whose Traditional Territories overlap with National Parks.

See <Mapping Change: Fostering a Culture of Reconciliation with Parks Canada>.

For example, the Government of British Columbia’s <Together for Wildlife Strategy> seeks to democratize the process of conserving and harvesting wildlife between Indigenous and non-Indigenous governments by including significant input from Indigenous Peoples across the province.

In <Pacific Rim National Park Reserve>, a wolf (Canis lupis) and human coexistence project is bringing together natural and social scientists with Indigenous leaders to find new ways to reduce conflict with coastal wolves in a culturally appropriate manner. Indigenous knowledge from members of ten Nuu-chah-nulth Nations—who have a deep history of coexistence with wolves—is helping to make one of Canada’s popular protected areas safer for people and wildlife.

RESOURCES

Stories from the Land: Indigenous Place Names in Canada

See: <https://maps.canada.ca/journal/content-en.html?lang=en&appid=0e585399e9474ccf932104a239d90652&appidalt=11756f2e3c454acdb214f950cf1e2f7d>.

Mapping Change: Fostering a Culture of Reconciliation with Parks Canada

See: <https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/agence-agency/aa-ia/reconciliation>.

Together for Wildlife: Improving Wildlife Stewardship and Habitat Conservation in British Columbia

<gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/plants-animals-ecosystems/wildlife/together-for-wildlife>.

Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, Parks Canada.

<pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/bc/pacificrim/plan/premieresnations-firstnations>.

Canadian Geographic Education’s <Canada’s Original Place Names> in Google Earth.

<https://earth.google.com/web/@55.95077959,-79.32641897,-3.37053057a,5664983.05540502d,35y,23.89357354h,0t,0r/data=Cj4SPBIgYmVjMmFjMDczMzhlMTFlOGEzYTFmZjM4NTk0YmQ5ZmEiGGVmZWVkX3JjZ3NfcGxhY2VfbmFtZXNfMA>.

QUESTIONS

What are the difficulties when it comes to mapping Indigenous territories?

How does the modern idea of a nation-state relate to Indigenous nations?

Who defines national boundaries, and who defines a nation?

Is it possible to imagine territory or nation outside today’s colonial frameworks?

Identify some of the obvious impacts of colonialism?

Consider how one might resist these intended and unintended consequences.

What is your sense of place?

How is your understanding of land and home implicated in colonialism?

Do Indigenous Place Names help/hinder your sense of nationhood?

Do any of the following words help you situate and locate your sense of self, place, and identity?

<Nation, Territory/Territories, Colonialism, Land Appropriation, Military Security, Economic Domination, Taxation, Resource Exploitation, Decolonization, Home, Indigenous Territories, Treaty Lands, Mapping, Maps, Cartography, Geographic Information System Mapping (GIS), Google Earth.>

resources: DO-IT-YOURSELF MAPPING

WIKIMINIATLAS

GEOHACKING<https://geohack.toolforge.org/>.

GPS VISUALIZER<https://www.gpsvisualizer.com/>.

GPS Visualizer is an online utility that creates maps and profiles from geographic data. It is free and easy to use, yet powerful and extremely customizable. Input can be in the form of GPS data (tracks and waypoints), driving routes, street addresses, or simple coordinates.

QUESTIONS

What is your relationship with MAPS and GPS?

Are you aware of your GPS coordinates?

Do you know how to find the proper and exact location?

Are these MAPS useful or harmful?

Do they contribute to or resist colonial ways of thinking about Indigenous people?

In what ways might today’s digital mapping tools resist or reinforce the authority to define land? How can cartography function as a form of political resistance and self-determination?

Are there other ways for you to disrupt and dismantle colonialism?

How can you practice decolonization?

IN WHAT WAYS MIGHT

TODAY’S DIGITAL MAPPING TOOLS

RESIST OR REINFORCE

THE AUTHORITY TO DEFINE LAND?

GOOGLE EARTH

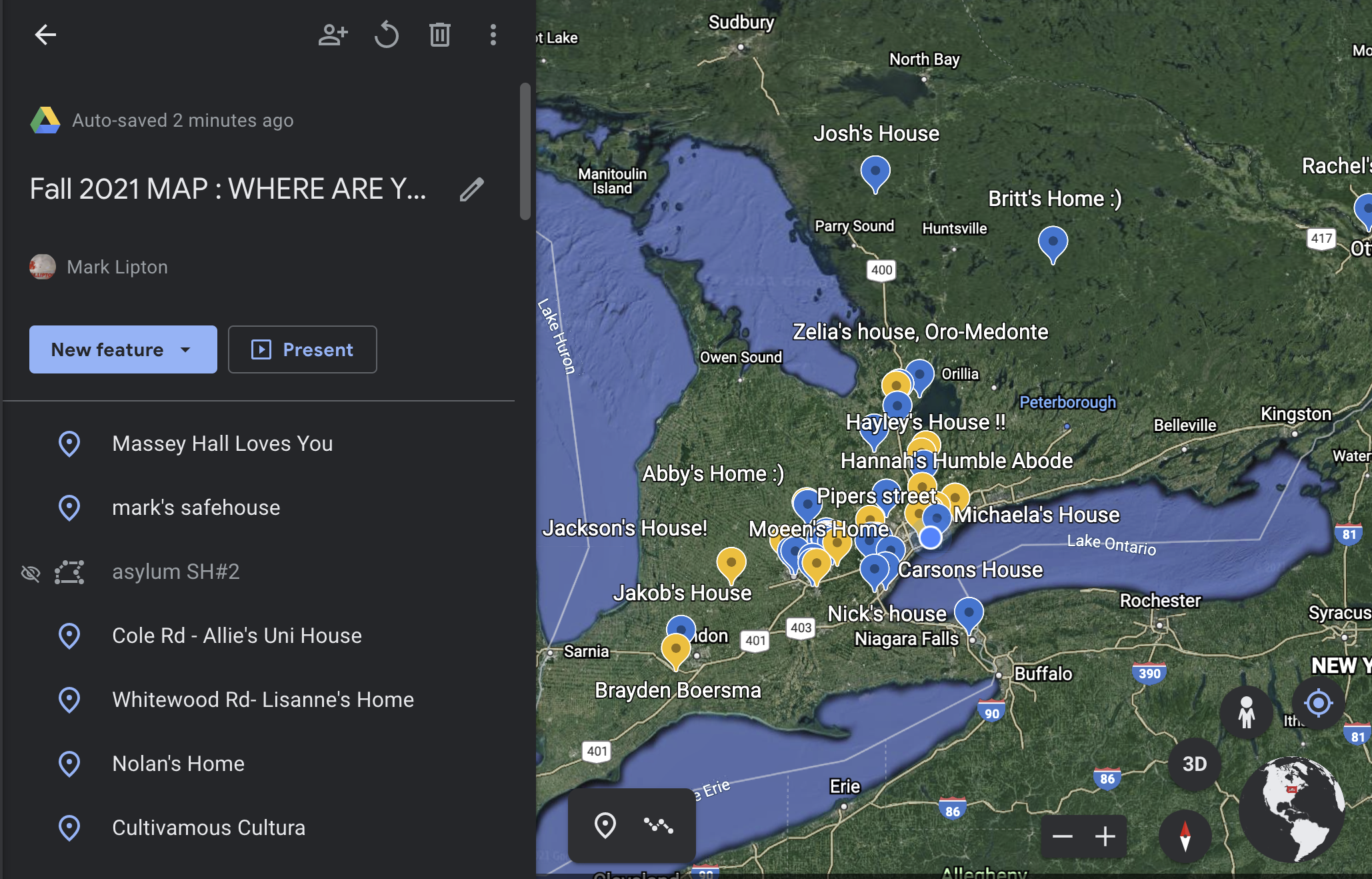

Originally designed by Keyhole, Inc., Google Earth is an interactive online computer program (written in C++) that maps the entire planet. The geobrowser relies on Geographic Information System Mapping (GIS) data along with satellite images/aerial photos create a three-dimensional map. The scale of cities & landscapes provides a sense of proportion and typography allowing users to embark on adventures and explorations. Interactive creation tools invite users to draw on the map, add photos, stories and other customizations that can then be shared. This is a link to the particular map on GOOGLE EARTH that we are working with: That is, the LANGUAGESOFMEDIA Google Earth Map. (The link is also attached below.)

GOOGLE EARTH <https://earth.google.com/earth/d/1OvWuIvY2gzTBcIKkPq21Sjnfp3cHcjkE?usp=sharing>.

MAPPING HOME

Where are you? Where is HOME?

Please follow the link to the Languages of Media GOOGLE EARTH page and map your location. You’ll see many placemarks from learners from last year. Add your placemark as a new feature in the map/project FALL2020/21/22 MAP: WHERE ARE YOU. Include your name and email address (if you are comfortable with this request—remember <no penalties>). Can you find other people in this class who are within proximal distance? Reach out to other learners and say hello.

Any intrepid explorers? I have hidden several safe houses around the world. Can you help me find them? WHERE IN THE WORLD IS @marklipton?

How might GOOGLE EARTH’s 3D version of the land impact your sense of HOME?

How might GOOGLE EARTH’s 3D version impact your understanding of INDIGENEITY? If so, how? How else could you use this 3D map?

Ten Principles of Technology

You use MEDIA every day & yet MEDIA is mostly using you.

Do you see how?

Do you know how?

Do you know what to do about it?

|

TO IMPROVE LIFE FOR OURSELVES & FOR OTHERS & FOR THE FUTURE. |

THERE IS A LOT you can do. Resistance is an option. CHANGE is possible. We are going to learn how to recognize these processes of cognitive takeover. How we surrender our cognitive powers to media. We are going to talk about how we can change to live the lives that we really want!

Your decisions drive change. The key is to make decisions guided by principles. To help with this, I turn to Neil Postman. In Postman’s assessments of technologies, media, and larger frames of meaning related to culture, he identifies ten principles that help us make meaning of technology, media, and its influences on global culture.

- All technological change is a Faustian bargain. For every advantage a new technology offers, there is always a corresponding disadvantage.

- The advantages and disadvantages of new technologies are never distributed evenly among the population. This means that every new technology benefit some and harms others.

- Embedded in every technology there is a powerful idea, sometimes two or three powerful ideas. Like language itself, technology predisposes us to favour and value certain perspectives and accomplishments and to subordinate others.

- A new technology usually makes war against an old technology. It competes with it for time, attention, money, prestige, and a “worldview”.

- Technological change is not additive; it is ecological. A new technology does not merely add something; it changes everything.

- Because of the symbolic forms in which information is encoded , different technologies have different intellectual and emotional biases.

- Because of the accessibility and speed at which information is encoded, different technologies have different political biases.

- Because of their physical form, different technologies have different sensory biases.

- Because of the conditions in which we attend them, different technologies have different social biases.

- Because of their technical and economic structure, different technologies have different content biases

Media Attributions

- 02 blog-banner

- island map