12 12: NARRATING WORLDVIEWS

THE LANGUAGES OF DIGITAL STORYTELLING

MEDIA LITERACY

For the last 30 years, I’ve witnessed teachers, policymakers and other stakeholders bounce around the term media literacy. It means different things to different folxs. If you are coming from an Ontario high school, media literacy was a required part of your Language Arts curriculum. In fact, I worked very hard with grassroots organizations fighting for the inclusion of media literacy.

Nonetheless, my research (also about media literacy and Ontario teachers) highlights how most teachers take an interpretive approach to the media literacy requirement. This means that you arrive in this class with a range of experiences and skills. And everyone comes from and starts at a different place. If you know your media literacy and are itching to make your video, you’ve already skipped through to the required parts of the assignment.

For anyone still unsure of how to approach the task of making a short digital story, this next section outlines some key ideas and points to useful resources.

Let me begin with seven key elements that are characteristic of effective digital stories. Please keep in mind that this process is open to your creative input and suggestions. Trust your instincts.

Creating a digital story is more purposeful than standard photography or moviemaking. Hopefully, you feel motivated to think critically and apply the knowledge and skill you currently possess to move forward. Whatever your interests or majors or past experiences, here is an opportunity to follow your curiosity and lean into your passions, values and strengths.

You are asked to document your creative process. The steps for you might begin with a brainstorming session; give yourself a short amount of time (20 minutes) to write out any and all ideas. Then, take time to sort and organize your ideas. Map them into themes and categories. Is there one set of ideas that really stand out? Follow your instincts. Learn to trust yourself. Follow your own hunches.

Step two. I suggest you give yourself two or three brief, timed-writing exercises. Set a timer to ring or beep after 15 minutes. When you begin, start writing out your story. Try this timed-writing at least three times. You can start over each time or continue where you left off; you are in charge. Your writing can include poetry, dialogue, detailed descriptions and/or standard narration.

YOU ARE ONLY LIMITED BY THE LIMITS OF YOUR IMAGINATION

(oh, & time & the law).

Once you have two or three pages of a story, you’re ready for the next step. In my day, one page of typed script was equal to one minute of screen time. You know your screen time is limited. You have two-and-a-half minutes to work with. Begin this step with a timeline. What does 150 seconds look like? Keep in the required use of titles, credits and some marking of Copywrite. How much time should you dedicate to titles?

Sketch out this timeline and consider how 150 seconds contains or limits the structure of your narrative. Will you have the standard rising action? Do you have a hook? Consider your story and which elements will work best within this timed schedule. Of course, you’re always free to start back at step one. Imagination and innovation are usually ITERATIVE; you often get so far before you need to stop and start again. This is all part of your creative process. You cannot do this wrong. As long as you persist.

The next step is to create some kind of storyboard of the key ideas. I request that your video include at least FIVE separate shots. Perhaps you draw five boxes and imagine your story as a comic book. Have you ever read comic books? Do you know HOW to READ comics? If this sounds interesting, please take a moment to enjoy the work of Scott McCloud.

Scott McCloud’s graphic essay, “Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art” is known around the world. Now published in thirteen languages, he is the key spokesperson for the genre of comics as a valid literary genre, not just pulp or kids’ stuff. Even if you have a favourite comic and have been reading the form all your life, McCloud’s presentation and book will help you imagine how to turn your sketch of an idea (based on your brainstorming, timed-writing and limited timeline) into a plan for a well-structured digital story.

COMICS

If not for Scott McCloud, graphic novels and webcomics might be enjoying a more modest Renaissance. The flourishing of cartooning in the ‘90s and ‘00s, particularly comic smithing on the Web, can be traced back to his major writings on the comics form.

His comic book about comics made him an evangelist for comics as an authorized literary form. McCloud coined the term “infinite canvas” for the new comics medium made possible with Web browsers. In this captivating look at the magic of comics, McCloud bends the format into a cartoon-like experience, where colorful diversions whiz through childhood fascinations and imagined futures.

SENTENCE STARTERS:

It wasn’t your fault. You’re not leaving, are you? Don’t leave. Don’t do this to yourself. I can’t just sit by and do nothing when you’re suffering so much. Just talk to me, please. You need help. Let me help you. Stop pushing everyone away. You haven’t been yourself lately. I’m not going anywhere. You’re hurting me. I can’t do this anymore. I need help. There’s nothing you can do. I need some time to myself. Leave me alone. It’s better this way. I can’t promise. Don’t make this harder than it already is. Stay with me. I don’t want your apology. You know I have feelings for you. Yeah, I remember the drill. I don’t believe it. This is breaking my heart. You met me a very strange time in my life. What keeps you up night? I let you down. Something strange happened. You’re not safe here. I wasn’t ready to say goodbye. We are not the same, and never will be. . .

BY HOOK OR BY CROOK

You are your story’s narrator. Before you start telling a story, you need a hook to attract audiences—invite their interest. At the same time, your listeners are listening and watching to determine why your story is important. What is your key message?

It’s important to be very clear on the central theme or plot point that you are building your story around. To amplify the challenges of your creative process, begin this storytelling exercise by answering two key elements: MESSAGE & AUDIENCE. All decisions about your story result from your key message and audience.

A great story progresses towards a central message. Begin knowing your message. Then, you can play around, figuring out the best way to illustrate it to you audience. A challenge is how you determine the best means to guide audiences to your message. The expressiveness of your voice and your ability to convey emotions, for example, are powerful ways to connect with an audience.

If it’s a funny story, build tension to a surprise or twist to leave your audience in stitches. Engaging stories increase dramatic suspense until its narrative peak. Regardless of what type of story you want to tell it’s important to be very clear on the central theme or plot point that you are building your story around.

Captivating stories don’t just share what happened and when — they also reveal how you felt, what motivated you, what helped you persist. Emotional story elements don’t have to be complicated. Try something as simple as these “troublesome” first lines:

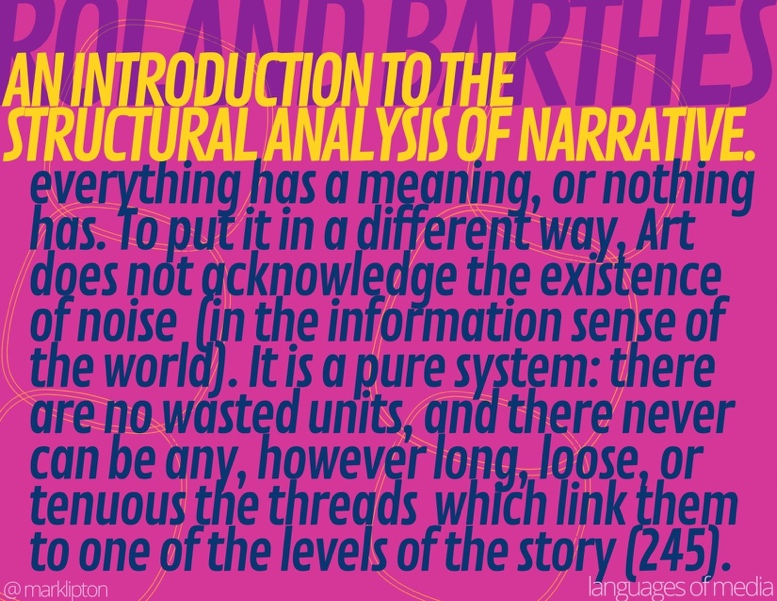

ELEMENTS OF NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

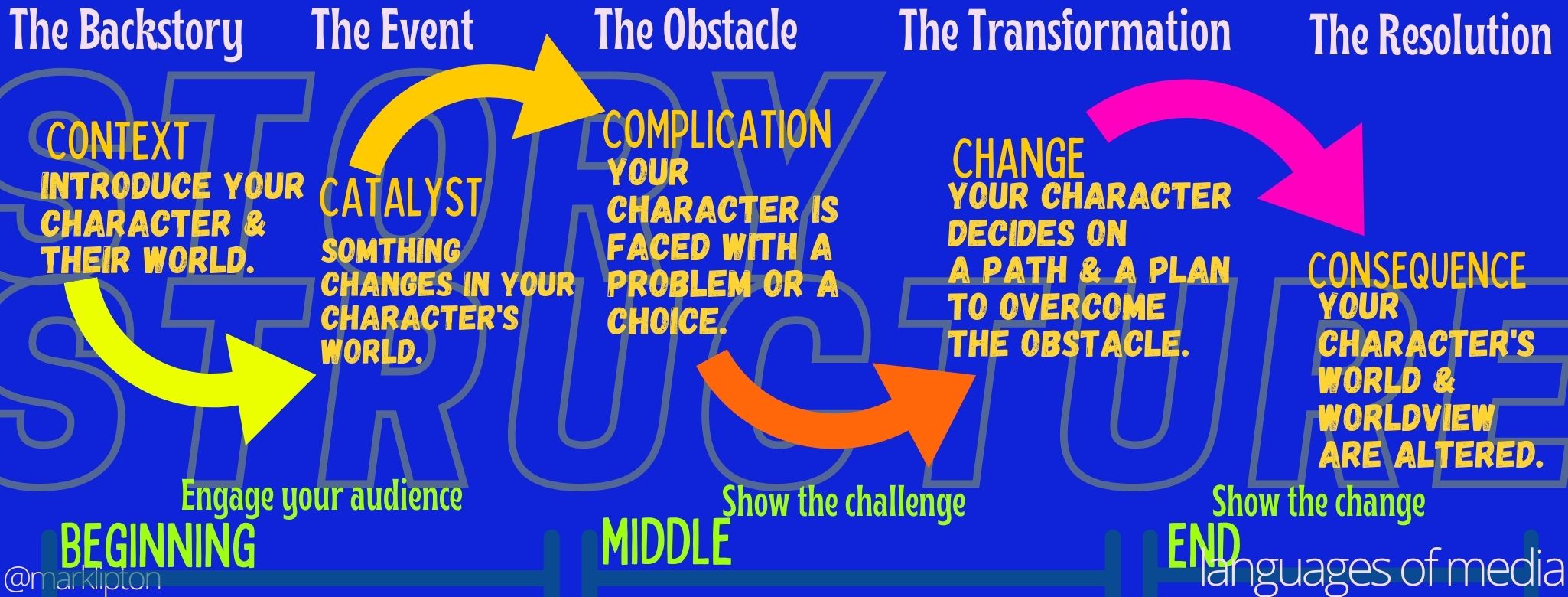

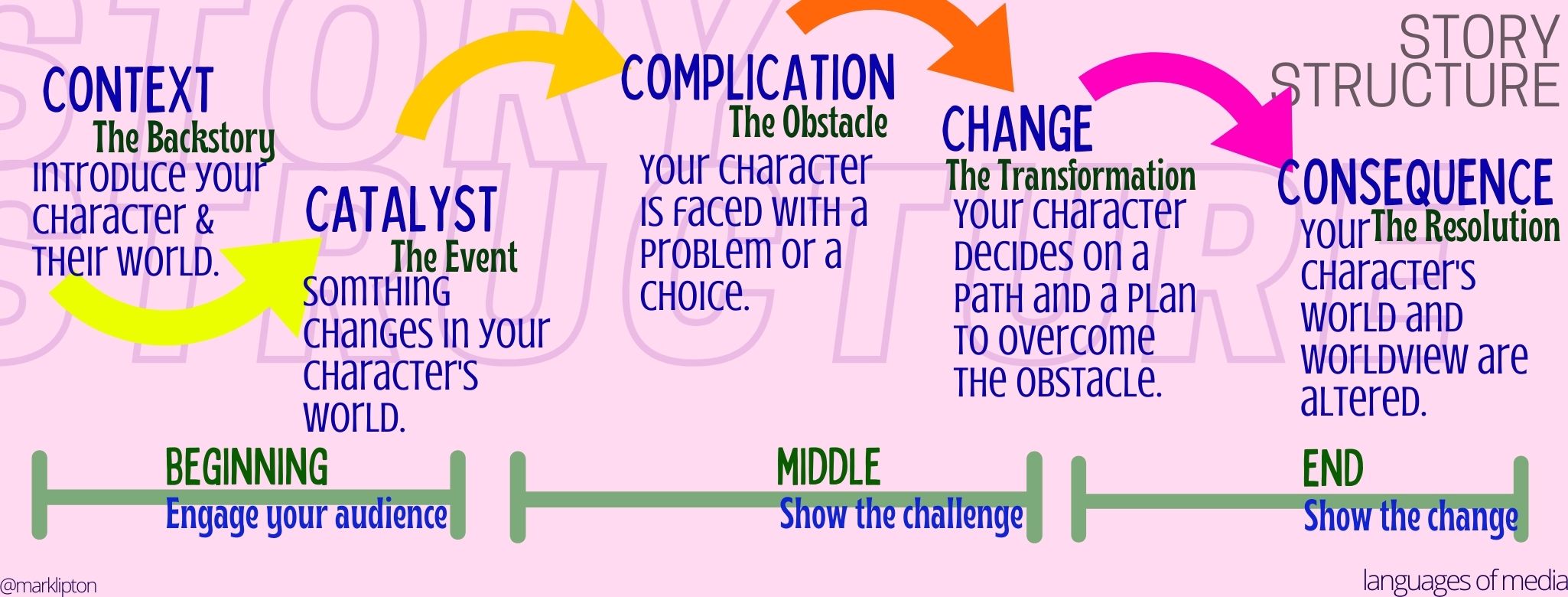

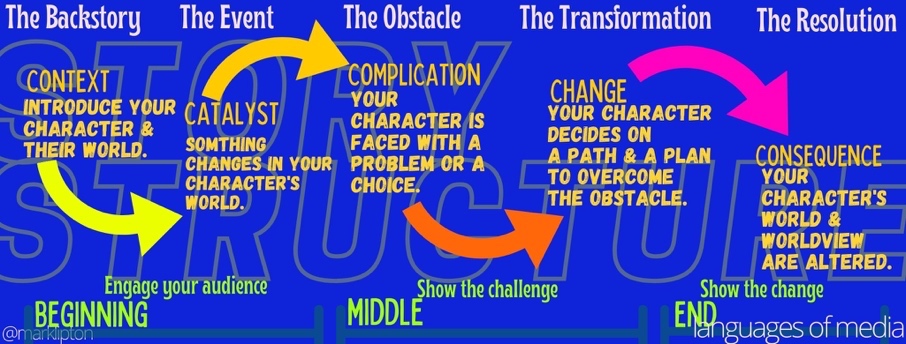

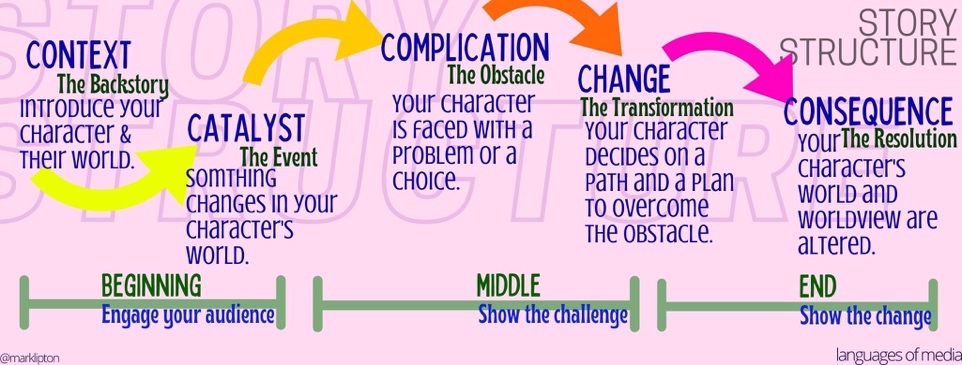

THE FIVE Cs OF STORY STRUCTURE

Narrative structure is a crucial element for creators and critics alike. Rather than encourage a simple three-part structure: beginning, middle, end, I point to another way to organize your story. For mapping your plot & moving the story forward, consider the following five words:

CONTEXT, CATALYST, COMPLICATION, CHANGE & CONSEQUENCE

I remember drawing this ‘story structure’ diagram when I was in my first year of university and the steps stayed with me. I do not know, nor do I have a formal source for the five Cs, save my old notebooks. Copied from a copy of something, my first year of university was rife with confusion, a sense of feeling lost—I had no sense of direction. My neat handwriting, doodling and colourful diagramming point (for me, at lease) to this structure as a beacon of light—a language for mapping my own story. Herein I share with you my notes and embellishments.

CONTEXT: THE BRIGHT LINE

When a story first begins, your audience will sit silently, in the dark, open to knowing what might happen next. Imagine them in a dark theatre –eating popcorn, getting comfortable. Don’t keep you audience completely in the dark; shed some flickering light on the background to your story: where are we? What year is it? What time is? Who do we meet? Invite your audience to wonder.

Providing contextual information situates time and place for audiences.

For years my father would come home from work and ask, “son, what’s the bright line today?”

And for years, I had no idea what he was talking about. I would sulk. Silently. Now I understand the metaphor.

My father is a lawyer—his metaphors usually relate to the law & legal affairs.

Within this CONTEXT, the bright line refers to a “clear distinction.” My dad was asking for some story about an event of the day. The bright line indicates a clear line when sulking ends and a fresh beginning unties a new narrative, bringing dad and me into some new world. [I was young. Poor dad. I must have sounded like, “Just a plain horse and wagon…”]

CATALYST: SHOT IN THE ARM

Recall a memory, if you can, of when you received your first injection. Likely a vaccination of some kind. Perhaps, in a pediatrician’s office? a worried parent bearing witness? tears? maybe a lollipop, if you were lucky?

This shot in the arm (or leg—some part of your body) functioned as a CATALYST to teach your body to recognize new diseases. That shot in the arm stimulated your body to make antibodies against antigens of pathogens, also priming your fighting immune cells to remember those antigens that cause infection for quick responses to future diseases.

Sorry if those were bad memories.

Sometimes we think of injections and vaccines as problems. Maybe these problems are simply “challenges” for us to confront. You need a needle? No big deal. In any event, these are not stories of misfortune. Okay, maybe someone cried. However, a challenge can also be something of your own choosing—you chose to give this class a try. Climbing towards a summit can be similar to climbing out of a hole, and whatever the source of your challenge, there might be a good story to inspire others?

If injection metaphors don’t work for you, how about challenges that led you to RISE to the occasion? A protest? A standing ovation? Catalysts and challenges are what lead you or your protagonist toward change. Events or experiences that lead something or someone to change in your (or your character’s) world. Can you identify a catalyst in your life? Or a challenge you accepted? How are these ideas specific to you and your story?

COMPLICATION: TOUGH NUT

If the catalyst is an event, then the COMPLICATION is the obstacle that presents choice. What are the options? Complications are always about some kind of struggle. COMPLICATIONS are conflict. What obstacles have you overcome?

Walking down the path of life, you confront a fork in the road. Which path will you take? Is this an interesting conflict? You take the high road and I’ll take the low road. . . A story without sufficient struggle or conflict isn’t very interesting. A story without a challenge –really, takes you nowhere.

CHANGE: DRUG OF CHOICE

Have you heard the expression “plus ça change”? The more things change, the more thing stay the same. “PLUS ÇA CHANGE.” I like the idea that, from moment to moment, the world is a completely different world and yet so much feels familiar and knowable. There are those things that remain constant. Like, for example, a rock. Do you want to sit through a story by and about a rock? Good stories take up complications as opportunities for transformation. CHANGE is a result of the decisions made when confronted with choice.

Maybe you had to decide between the University of Guelph or the University of Toronto? You made a judgment call! The choice you made is going to transform you. Every experience, any new transactions will change you. CHANGE is inevitable. Your selection of this university, of this class, etc. represent your plan to overcome life’s current obstacles.

When a doctor makes a diagnosis and when this doctor prescribes some medical remedy—that doctor demonstrates courage. Why this disease? Why that pill? In truth, there might be many possible options. Where does the doctor get the courage to diagnose a patient? Medical school and experience help.

[even then, how do you know your doctor wasn’t a C student?]

These credentials (hopefully) give both doctor and patient courage and hope to carry on. Wellness plan in place.

CONSEQUENCE: MATTER OF COURSE

Yes, life goes on. And every good story comes to a final resolution that closes the experience. The CONSEQUENCES in your story often highlight how (you or) your character’s world and worldview are altered.

Let’s say you’re on a ship and there’s a shiny brass bell. The sign above the bell reads “do not touch.” You cannot un-ring that bell. You are responsible for the choices you make. Now, you must live with short term outcomes as well as far-reaching, unintended consequences. Still tempted to ring the bell? what could be so bad?

What emotional responses do you want audiences to experience? What lesson do you want to teach your audiences? What did you learn from the outcome? How did it feel? Why?

With contextual knowledge, hook your audiences’ attention as they situate your story and settle in, ready to be taken to another world; arrest their attention with some catalyst that challenges your hero and audience—what will happen next? Present an interest obstacle to your audiences that complicates your story; let the audience follow your hero’s logical plan to meet and overcome this difficulty and show how your hero is transformed as a result. Finally, your audience wants some resolution, ending your story with an outcome that follow orderly narrative structure.

GUIDELINES FOR ADVANCED ANALYSIS

This section reviews five kinds of advanced analysis. These include formal; genre; auteurist; comparative aesthetics; and sociological/political. Each category asks a number of questions.

FORMAL

1. What seems to you to be the special quality of your film’s form? How would you characterize the look of the movie — its imagery, its patterns of light and darkness, its overall visual texture?

2. What kinds of reality does your film present? Objective, subjective, fantastic, subconscious? Are there varieties of reality within your film? If so, how does the film signal the level of reality at any given point? (Distortion? Fades?)

3. Consider the organization of materials. Does your film follow a strict linear and/or chronological order? Or does it shatter traditional notions of continuity? Are there flashbacks or flashforwards?

4. Is the cinematography naturalistic or stylized? Is there any use of slow motion or accelerated motion? Are there any freeze frames, superimpositions, zoom shots, etc.? If so, to what effect are these devices put?

5. Consider the camera angles, the organization of space in the various shots. Does there seem to be a particular pattern in the use of close-ups and/or distance shots? Is there any sequence or shot that seemed to you especially noteworthy? Why?

6. To what extent does your film use visual motifs–images, symbols — to establish and express its themes, to convey its attitudes towards its materials?

7. Consider your film’s editing. Does it seem “invisible,” the flow between shots and sequences smooth? Or does the film make use of transitional devices that call attention to themselves? (Wipes? Irises? Jump Cuts?) To what extent does the tempo of the editing serve to expand or condense time?

8. How would you characterize the film’s overall rhythm or tempo? How is it established?

9. What part do music, silence, sound effects play in the total effect of your film?

10. In what ways can the form of the film be said to carry its meaning?

GENRE

1. To what “genre” does your film belong and in what ways is it typical of its kind? (Consider patterns of plot, character, setting, iconography.)

2. In what ways does the film depart from the typical patterns of its genre?

3. If genre is, as many believe, an important manifestation of a psychological aspect of mass culture, what does this particular genre (coming at this time and this place) tell us about ourselves and our culture?

4. Artistically and intellectually, what criteria can you apply to evaluate your film? Is it a lesser or superior instance of its kind by virtue of its originality (departure from generic elements) or typicality (faithfulness to the patterns of its kind)?

AUTEURIST

1. In terms of your film, how would you describe your style? (e.g.: intellectual and rational or emotional and sensual? calm and quiet or fast-paced and exciting; polished and smooth or rough and crude-cut; tightly structure or loosely structured; realistic or romantic; restrained or exaggerated; etc.)

2. What basic similarities does this film have to other works you have made? How is it significantly different? (Take theme, character, story, visual elements, and sound effects into account here.)

3. What is the quality of this film as compared to other works you have made? As compared to his other films, how well does this film seem to reflect your philosophy, personality, and artistic vision?

4. Does your film suggest a growth in some new direction? If so, describe that new direction?

COMPARATIVE AESTHETICS

1. Is the film version a close or a loose adaptation of your life? If it is a loose adaptation, does the departure seem due to the problems caused by the medium, or by the change in creative expression?

2. Does your film version successfully capture the spirit or essence you intend? If not, why not and how do you think it fails?

3. What are the major differences in structure between your real life and the film? Consider point of view, sequence, temporal elements, etc.

4. How well do the actors fit your preconceived notions of the characters? Which actors fit your mental image best? Which least? How do your responses to these performers affect your response to the film as a whole?

SOCIOLOGICAL/POLITICAL

1. What is the social/political problem the film treats? What attitudes are we being asked to take towards it? How do you know? (Consider story line, characters, cinematography, etc.)

2. To what extent does this social problem have a universal or timeless quality, affecting all people in all time periods, or is it restricted to a relatively narrow time and place?

3. How much of the film’s impact seems to depend upon its relevance to a current problem and its timing in attacking this problem? Would you say that the film is attempting to influence beliefs and actions?

4. How would you describe your film’s ideological stance? Does it seem to you to be consistent or at odds with the dominant ideology of its time and place?

5. Does the film seem to you polemical in texture? If so, how persuasive are its arguments? Do you agree or disagree with its views? How does your agreement (or disagreement) affect your assessment of its aesthetic values and social impact?

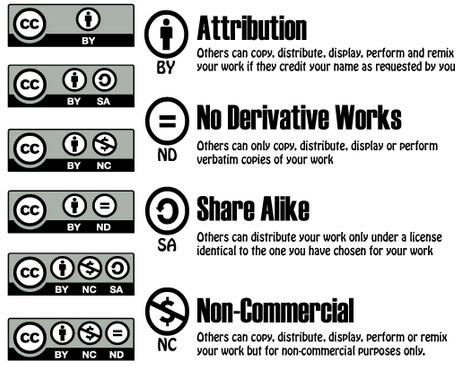

CANADIAN COPYRIGHT LAWS, FAIR DEALING & CREATIVE COMMONS

It is important to distinguish ‘fair dealing’ from ‘fair use’. The fair use exception in U.S. copyright law is NOT the equivalent of fair dealing in Canadian law. The wording of the two exceptions is different. It is important to make sure that you consider the Canadian law and are not relying on U.S. information, which has no jurisdiction in Canada.

In Canada, consumers have certain rights to use copyrighted material without permission or license from the owner of the copyright

To determine if something is Fair Dealing, a two-part test is applied.

The first test is whether or not the use falls under one of the exemptions: research, private study, criticism or review, news reporting, parody and satire or education.

RESEARCH most often involves academic research but the courts have defined it more broadly to include nearly any kind of research; for instance, posting 30-second clips of songs on a website that sold digital music was determined to be fair use because it enabled consumers to do research in deciding whether or not to buy the songs.

PRIVATE STUDY is just that: the making of a single copy for your own use (for example, photocopying or hand-copying sections of a book for reference). Private study explicitly does not include work done for a class or training program.

CRITICISM OR REVIEW includes examples such as quoting from a novel or film (in which case the “quote” might be a video clip) in a review or quoting from an academic work in order to argue against its point. Court rulings have suggested that to fall under criticism or review, the use must be critical of the work being used; for instance, it was ruled that a biography of Shania Twain could not use an interview with the singer taken from another book because it was simply reprinting the interview without critiquing it.

NEWS REPORTING is perhaps the most self-evident exemption. It applies to reporting in any medium and users do not have to be recognized journalists; bloggers, for instance, could claim this exemption if they were engaged in news reporting.

PARODY AND SATIRE means either the “spoofing” or sending-up of a particular work (such as the parodies of movies and TV shows found in places such as Mad Magazine and This Hour Has 22 Minutes) and, more broadly, the use of a work to make a social or political point through humour.

EDUCATION is, obviously, the exemption most relevant to learners. Although there are more specific detailed exemptions for education laid out in other sections, how education applies to Fair Dealing is not explained in the Act. It seems certain that it will include formal education in a classroom but whether and how it will apply to online and distance education, homeschooling or other contexts is not yet clear.

If a use falls under one of the exemptions defined in the Copyright Act, six factors are then considered.

1. What is the purpose of the dealing? In general, the more worthwhile the use is seen to be, the more likely it is to be considered Fair Dealing. This includes non-commercial purposes and purposes where the public good is served, though commercial purposes may still be Fair Dealing.

2. What is the character of the dealing? This question asks what was done with the work. If the work was copied, how many copies were made? How widely were they distributed or made available? Were copies destroyed after use? Did the use follow standard industry practice?

3. What is the amount of the dealing? Contrary to popular belief, there is no “safe” amount of any text that can be used without infringement. How much of a work is used is one of the questions considered, but “it may be possible to deal fairly with a whole work” – particularly in the case of texts such as photographs or advertisements.

4. What alternatives to the dealing are available? How important was the copyrighted work to the use? Could the same purpose be achieved with a work that was not under copyright? (Note, however, that the Court ruled that the possibility of using a licensed work was not relevant to determining whether a use was fair or not.)

5. What is the nature of the work? There are two issues here. First, the Court found that it was more likely to be Fair Dealing if a work was unpublished, rather than published (since it would make the work more widely available). However, a use was less likely to be Fair Dealing if the work was confidential.

6. What is the effect of the dealing on the work? If the value of the original work, or the market for it, is likely to be harmed by the use, then it is less likely to be Fair Dealing. This is particularly true if the new work competes directly with the original. It’s important to keep in mind, though, that this is only one of the factors under consideration, so a use that fails this test – quotations from a book in a negative review, for instance, or a parody of a film – can still be Fair Dealing.

|

COPYRIGHTED WORKS: Anything created in any form (e.g. text, music, video, image) is automatically protected under copyright law—whether the creator wanted it protected or not! Copyright law restricts others’ abilities to use, display, or share that creation. PUBLIC DOMAIN: Something that has passed out of copyright protection. For example, Mozart’s symphonies, which are old enough to no longer be copyrighted (although a particular performance of them might be!). CREATIVE COMMONS: The alternative to blanket copyright protection. If a creator wants to give more freedom to how people use his/her material, they can license it as creative commons. |

When CITING sources please include:

Title of the work; author or creator; year; source <where you found the source, specifically, so we can find it too.>; license <tell us what kind of license the source uses. If we know the license, we know if we can use it too. Licenses include: ©copyright; (cc) Creative Commons CC; & public domain>.

QUESTIONS

What is meant by the commons?

What is the state of the commons?

Do you know how to give attribution & assign licensing?

RESOURCEhttps://creativecommons.org/use-remix/

|

QUESTION

Hausknecht, Vanchu-Orosco & Kaufman suggest the creation and sharing of digital stories may enhance wellness. Do you agree? Why or why not? If so, how?