3 03: SYNECDOCHE /səˈnekdəkē/

Watch your thoughts, for they become your words; be careful of your words, for they become your actions; watch your actions for they become your habits; be careful of your habits for they form your character; and mind your character because it becomes your destiny!

ATTENTION: I JUST SAW THE IRON LADY. IT WAS GREAT!

I hate Meryl Streep. I know, for some of you that must seem like a crazy proposition. Hate is a bad word. But I hate her. I hate her like I hate cats. And I’m allergic to cats. I know she’s won every acting trophy. Yet I have a strong reaction to seeing Meryl Streep as a popular culture text and I’ve been conditioned to reinforce my reaction in the years since I’ve been watching her on the Hollywood scene. Maybe you like her. That’s okay. I don’t mind. You’re entitled to your opinion. I like to say to my students that freedom of expression in the classroom is an undeniable right. I may disagree with you, but I will defend to the death your right to your opinion. So you like Meryl. Go ahead. She still bugs me. Nonetheless I was dragged to see the biopic Iron Lady where I get to spy Meryl slowly losing her marbles, as the character emerges with Alzheimer’s disease.

The character in this film is Margaret Thatcher, known to many as the longest serving Prime Minister of United Kingdom from 1979-1990; she was the first female Prime Minister as well as the Leader of the Conservative party. Thatcher, however, is not one of the U.K.’s most cherished Prime Ministers. Thatcher was expelled from office, forced out of government by her own cabinet members and succeeded by John Major. Perhaps it was because of her ultra conservative values; maybe it was due to a public backlash against many of her policies (particularly an unpopular Poll Tax). Nonetheless, this Thatcher is a sad lady. And there is Meryl. Good old Meryl. Meryl now has another gold trophy. Lucky her.

I begin this chapter with my story of Meryl, Margaret, and the movie because the film’s author (screenwriter Abi Morgan) penned some powerful lines of dialogue that encapsulate some of my pedagogical practice when it comes to doing media studies.

In the film, an elderly Thatcher remarks to her doctor:

People don’t think any more, they feel. One of the greatest problems of our age is that we are governed by people who care more about feelings than they do about thoughts and ideas. Now, thoughts and ideas, that’s what interests me.

Thatcher continues,

Watch your thoughts, for they become words. Watch your words, for they become actions. Watch your actions, for they become habits. Watch your habits, for they become character. Watch your character, for it becomes your destiny.

I repeat these spoken lines of dialogue throughout the semester using my worst possible Meryl Streep accents. My point is to introduce to all learners a critical principle when taking up the challenge of doing media studies. Here it is; when looking at media messages or “texts” your brain generally engages in two actions: you either ignore the text (because it doesn’t matter to you) or you react to the thing.

Oh, there’s Meryl again. I hate her. I am responding uncritically. This is simply how I feel.

I want to offer two axioms of communication about the ways in which humans respond to media texts and messages. First, your response will most likely be analogous to the way you responded to a similar text in your past. Second, the way you respond to that text will say a lot more about YOU then the actual text. These two axioms about response are how I introduce students to critical analysis.

TWO AXIOMS OF COMMUNICATIVE RESPONSES/REACTIONS:

ONE

a response to any text (based on a past experience & memory)

imitates &/or emulates previous responds to similar texts (from the past);

TWO

any response to a text reveals a great deal more about

the speaker than the object—the actual text.

To reiterate: I hate Meryl Streep.

Not because she’s a good or bad actor. Her skill at her craft has nothing to do with my response. Hate is a feeling. I’m not engaging in thoughtful critical analysis when I write how I hate Meryl. I am feeling. To some, my feelings are funny; to others, insulting, rude, vacuous, insincere. Please don’t think Ms. Streep’s ability as an actor has anything to do with my personal feelings. My feelings are based on an entirely different set of personal connotations that, at this point, I’d like to remain a mystery.

There are more interesting questions to ask that redirect my response away from feelings toward critical analysis—thinking. In forming a critical analysis of Meryl one might ask: Why has Meryl won all those awards? What is it about her performance in this film that led her peers to celebrate her achievements? What evidence can you discover that reveals how she embodies a character? What are the criteria for outstanding actors?

My feelings, however, prevent me from careful analysis that would provide me with an exacting answer to these questions. That is, when you see something, whether you like—or hate, your affective response often prevents or inhibits critical analysis.

The point I need to make is that feelings don’t help me as a student of media when formulating opinions about texts.

|

If I want my opinions to count— my thoughts, beliefs, and judgments all need to be based on a solid foundation of reading texts & constructing meaning in significant ways. |

CRITICAL THINKING

By significant ways, I refer to the process of critical thinking.

Scriven, M. & Paul, R. (1987). Critical thinking as defined by the National Council for Excellence. in Critical Thinking. Proc. of 8th Annual International Conf. on Critical Thinking and Education Reform. Retrieved July 30, 2021, from <http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766>.

When doing media studies, begin by noting the intellectual differences between feeling and critical thinking. I cannot say I really hate Meryl Streep when I apply critical thinking to her as a text. I notice, for example, her ability to adopt the verbal and nonverbal distinctiveness of a character; Meryl captures the qualities of a frail old lady with a twitch of her chin while reflecting the character’s hot temper by regulating the pitch and tenor of voice. When I watch this actor on screen, Meryl Streep (the human, the celebrity) disappears and I am welcomed into the world of the film.

QUESTIONS

What assumptions do you bring to bear as a student? What assumptions direct your understanding of this course? What are your expectations for this course? So far, how are you feeling? What are you thinking?

THE FUTURE IS NOW: CHANGE

All change is ecological, not additive.

You cannot change too much at once without great stress.

Theories about schools and learning mostly fail to adapt to a changing culture—a global, visual, mediated environment that is increasingly on the verge of changing still. To articulate technological developments and changes in the media environments as a decline (or death of civilization) is mostly reductive, if not essentialist. Instead, a media determinist lens can be a useful tool for understanding change.

Change isn’t new. What is new is the degree of change. The degree of change for the school reform movement of the 1960s is not the same degree as those changes occurring in the 21st century. Educators must be aware that the human situation today is without precedent.

Historians of education often describes how most practical approaches to learning are based on a 100-year-old tradition—if not ancient.

Change—or lack of change, highlights how and why school is dead. It’s not enough to say that learners who find themselves in a changing technological environment face the choice of engaging or resisting change. Instead, systems of education and learning must put aside its long-held beliefs, practices and attitudes and begin to assess and apply the implications of technological change. All learners and all learning must try to keep abreast of how ever-changing media environments implicate learning.

To make matters a bit more complicated –we are living in a time of unprecedented technological change. We need to take matters into our own hands and decide what learning means in today’s social context. To this end, I ask you to articulate a theory of media change that is ecological. By adopting the biological metaphor, media are understood as a complex, transitory environments.

A medium is an environment in which a culture grows.

Media are environments for culture systems.

QUESTIONS

Can you describe any recent CHANGES? How have you, as a learner, changed? What does it mean to be a learner? What are schools for? What are teachers for?

LEARNING ECOLOGIES

Since you began learning online, how have you tried to enhance your learning environment? How do your surroundings impact your ability to learn? Describe your learning ecology?

Learning during the time of COVID introduces an opportunity to have greater control over your LEARNING ECOLOGIES. For example, how might your current physical environment impact your sense of learning? Learning online is not the same a learning in a classroom. What changes stand out for you as reducing your power to learn? What changes may promote your abilities to learn? There’s always a give and take. And in this context, you have agency to control where you learn.

This is a good example of your relationship with media. Do you see your agency and negotiate your media uses to enhance your life? Or perhaps, media are tools that control your actions, language, even your thoughts.

Do you use media?

Or are media using you?

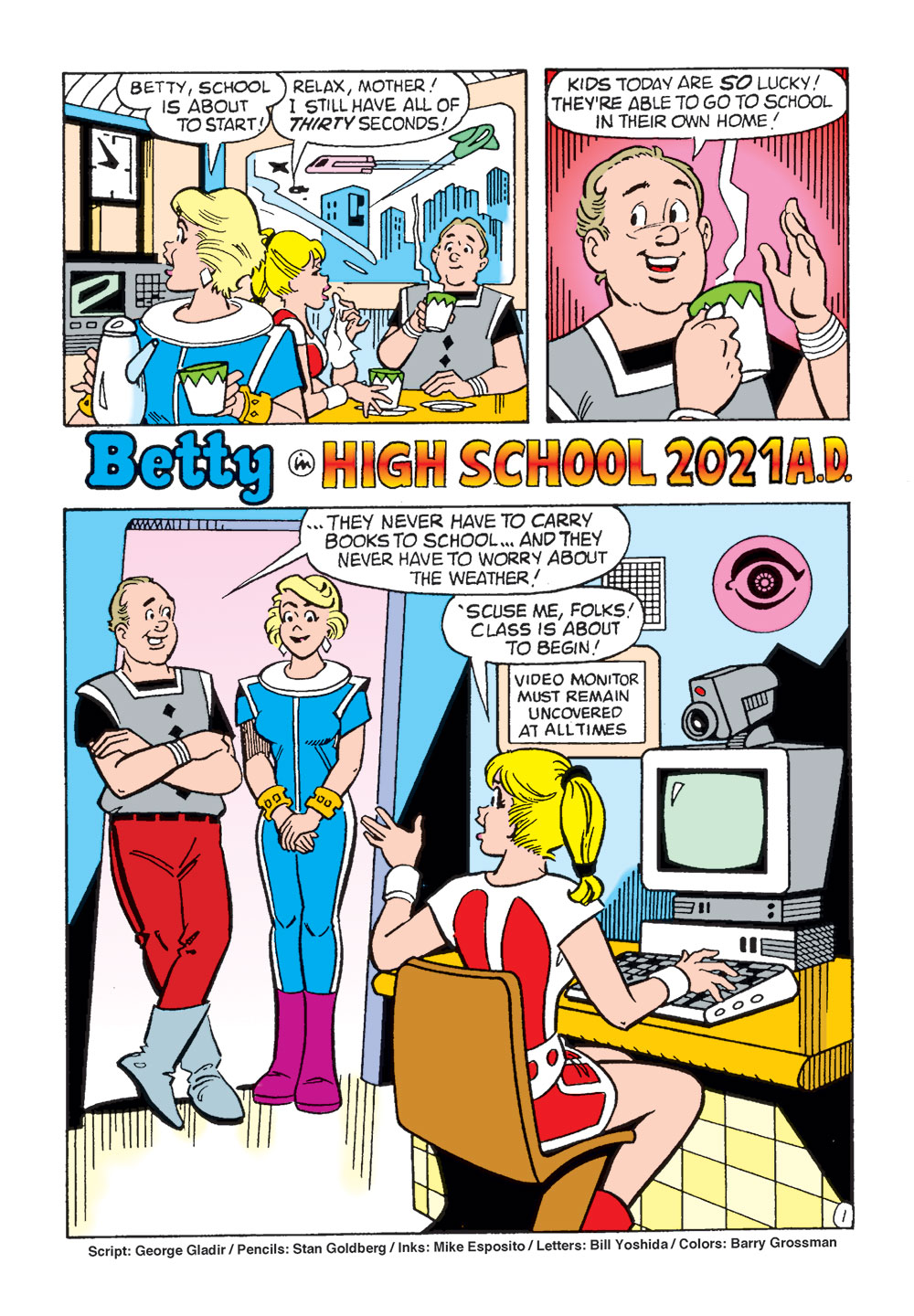

Betty in High School 2021 A.D. was written by George Gladir, with art by Stan Goldberg, Mike Esposito, Bill Yoshida, and Barry Grossman. Notice the very large camera sitting atop the monitor. A sign on the wall reads “video monitor must remain uncovered at all times.” Visible on the wall behind Betty’s desk, a giant pink eye suggests the state of Betty’s learning ecology; her bedroom is now a site of state surveillance.

MEDIA ECOLOGY

All change is ecological, not additive.

A MEDIUM is and ENVIRONMENT in which a CULTURE grows.

Petri dish with pipette and blood sample – Stock Image – F017/2944. Science Photo Library; Effects by m.lipton

MEDIUM vs. MEDIA

Recognize the difference between the words medium and media. The former, medium, is the singular form; media are plural.

1. something in a middle position;

2. a means of effecting or conveying something, such as a substance regarded as the means of transmission of a force or effect, e.g.,

Air is the medium that conveys sound.

3. a channel or system of communication, information, or entertainment;

4. a mode of artistic expression or communication;

5. a condition or environment in which something may function or flourish.

Etymology for medium (noun and adjective) Latin, from neuter of medius middle.

Source: “Medium.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/medium.

LINGUISTIC RELATIVITY

My starting point considers that words do not have meanings, people do; the word is not the thing. In this way, language reflects and conditions our thinking and behavior.

In fact, the easiest way to manage change and to make change is to focus on your language habits. Changing the ways we use language can change our patterns of thought and behavior. Thinking depends on language. Different language structures result in different patterns of thought, which provoke different behaviours, actions, and habits.

There are four main points to this theory of linguistic relativity.

ONE: Language is way of cutting up experience into categories. Different languages cut up the world differently.

TWO: Several linguistic elements define the different ways languages represent and dissect the world; note the four (4) distinct levels: (1) vocabulary and words; (2) morphology includes those bits that make up words (these include roots, suffixes, prefixes, infixes; as in “cat” + “s” = plural; or “walk” + “ed” = past tense); (3) syntax/grammar (paradigm/syntagm) and the rules for putting words together; & (4) metaphors, where the use of one concept is used to describe something very different.

THREE: Children naturally learn how language cuts up their world. This learning tends to be internalized around the age of seven.

FOUR: The structure of our language determines our structures of thought.

THE MAP IS NOT THE TERRITORY

Consider the differences between MAPS and TERRITORIES.

Humans live in two worlds:

| Words | Things (non-words) |

| (map) | (territory) |

The more a map corresponds to territory, the better the map. Most misunderstandings or mistakes are the result of confusing the MAP with the TERRITORY.

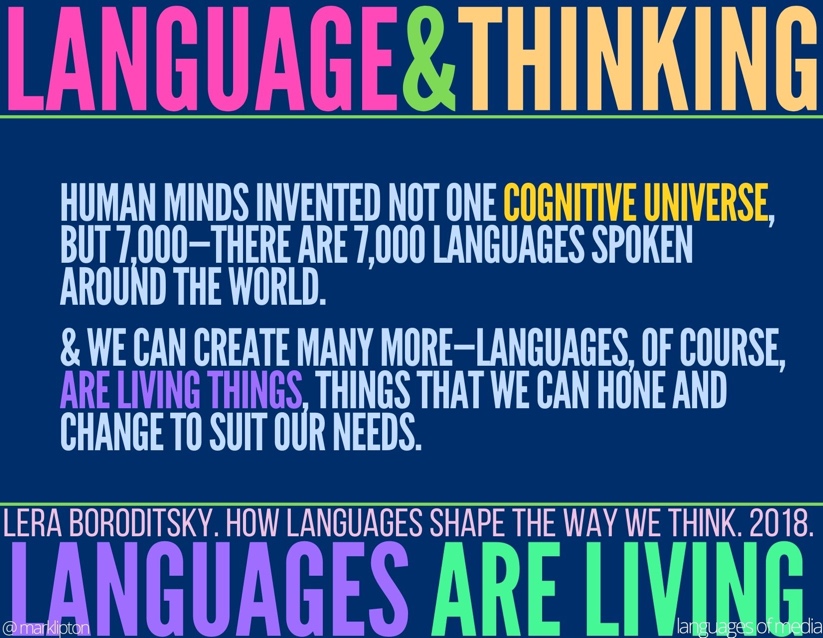

Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky shares examples of language, from an Aboriginal community in Australia that uses cardinal directions instead of left and right, to the multiple words for blue in Russian, to suggest the answer is a resounding yes. Lera Boroditsky (2018) talks about the relationship between language and thought in her talk. “The beauty of linguistic diversity is that it reveals to us just how ingenious and how flexible the human mind is,” Boroditsky says. “Human minds have invented not one cognitive universe, but 7,000.”

RESOURCE

Lera Boroditsky—How Language Shapes the Way We Think. 2018. (14:13)

<https://youtu.be/RKK7wGAYP6k>.

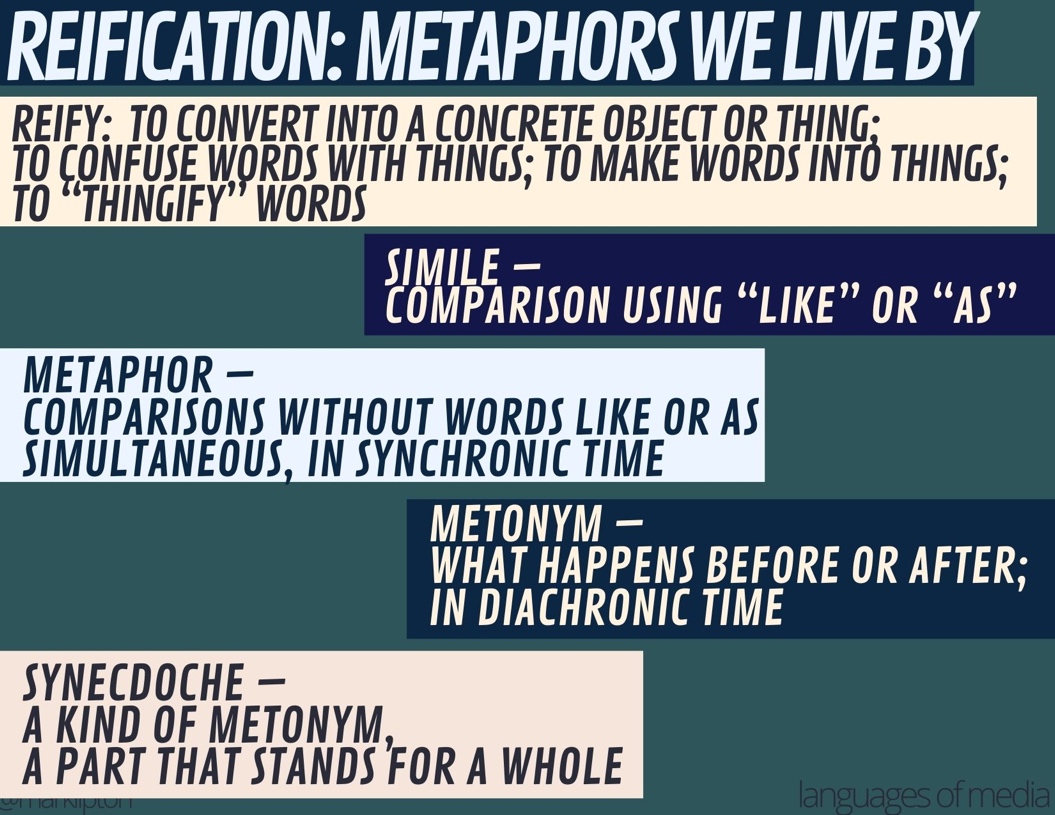

REIFICATION: METAPHORS WE LIVE BY

All metaphors rely on reification (from verb: reify—make something abstract more concrete or real); from Latin res (thing) and –fication suffix for facer (to make).

REIFY describes the cognitive process whereby words are converted into a concrete object or thing; to confuse words with things; to make words into things; to “thingify” words.

Reification refers to the fallacy of ambiguity; when an abstraction (abstract belief or hypothetical construct) is treated as if it were a concrete real event or physical entity; the error of treating something that is not concrete, such as an idea, as a concrete thing. A common case of reification is confusion of a model with reality or “the map is not the territory.”

It’s a though we respond to symbols as if they “are” what they mean. This refers to the illusion that things have names and we have magically forgotten that “names” are “words” for what humans call things. Names appear to be part of nature; however, the name is not the thing. With reification, the word has become more important than the thing, taking on a life of its own.

This idea seems obvious. It is easy to understand but challenging to remember and practice. When we assume the thing and its name are “the same” we encounter problems.

Naming is a conscious human act not an act of nature. The names we give something will always reflect our point of view.

| A terrorist is a freedom fighter A freedom fighter is a terrorist. |

SYNESTHESIA

James Geary’s short talk Metaphorically Speaking, defines metaphor simply:

|

Aristotle’s classic definition of |

RESOURCE

James Geary—Metaphorically Speaking. 2009. (9:26).

<https://www.ted.com/talks/james_geary_metaphorically_speaking?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare>.

PATTERN RECOGNITION

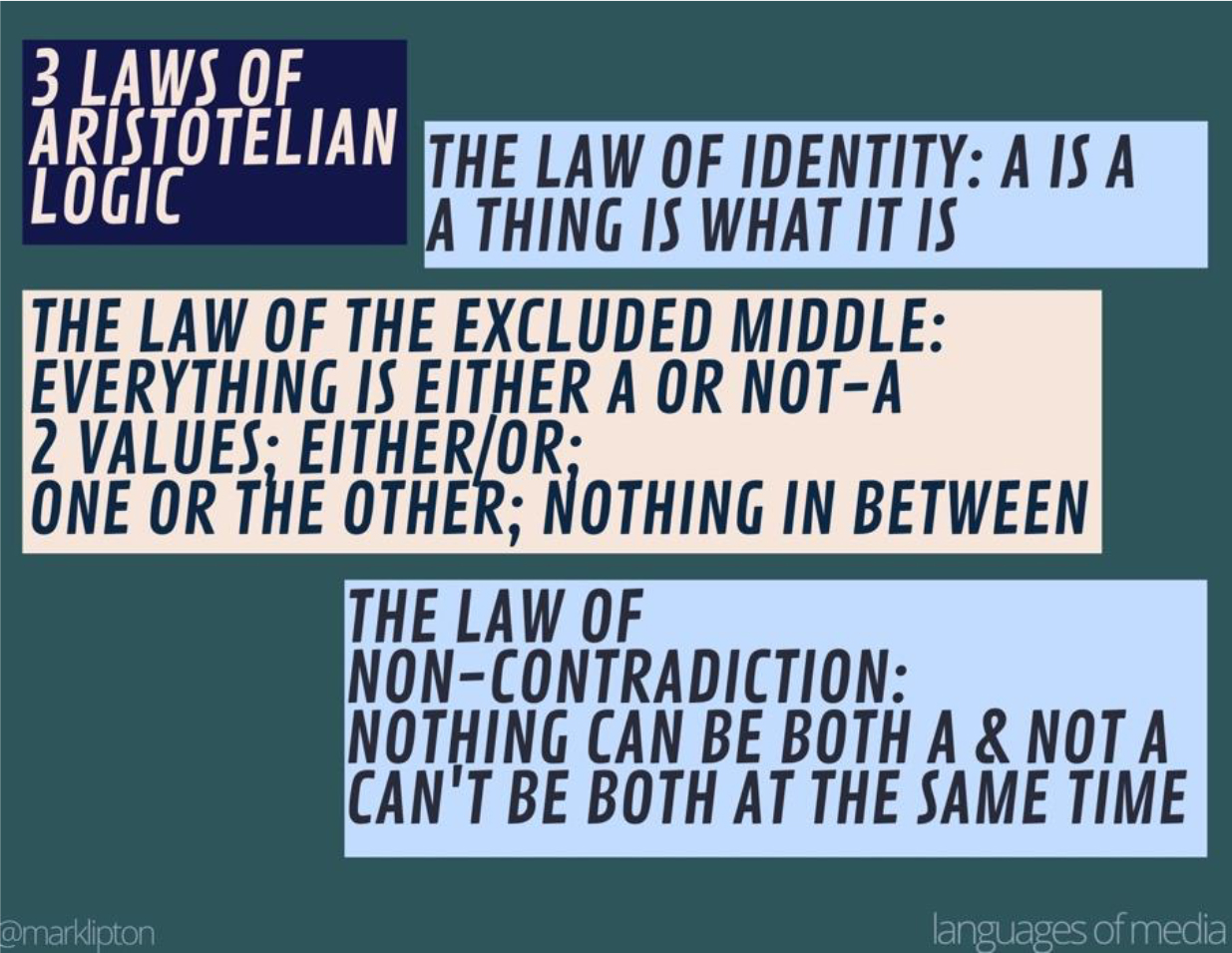

To consider media and language, it is useful to acknowledge Aristotle’s major contribution to human communication systems in the form of his logical propositions. ONE: The law of identity: A is A. A thing is what it is. TWO: The law of the excluded middle: everything is either A or not A. There are only two values: either/or; one or the other; nothing in between. THREE: The Law of Non-Contradiction: nothing can be both A and not A; can’t be both at the same time.

— stop. For a second, close your eyes; shield your sense from the magic of my words—here it is time to pause. Take a moment. Consider: as you read, do you feel sensations in your body that my cue reactivity? Pause. Reflect. Consider. What is your considered response?

Aristotelian thinking may have magically helped direct language and civilization and power and authority; however, it is always wise to reconsider where our meanings come from; how current media ecologies function in the consuming time of late capitalism. In other words, Aristotle fuck’d us up. The world is never a question of A or not-A; zero or one; female or male; fight or flight; black or white; good or evil; kind or cruel, yin or yang; right or wrong; pass or fail. Aristotle led Western logic and systems of making meaning into an either/or worldview.

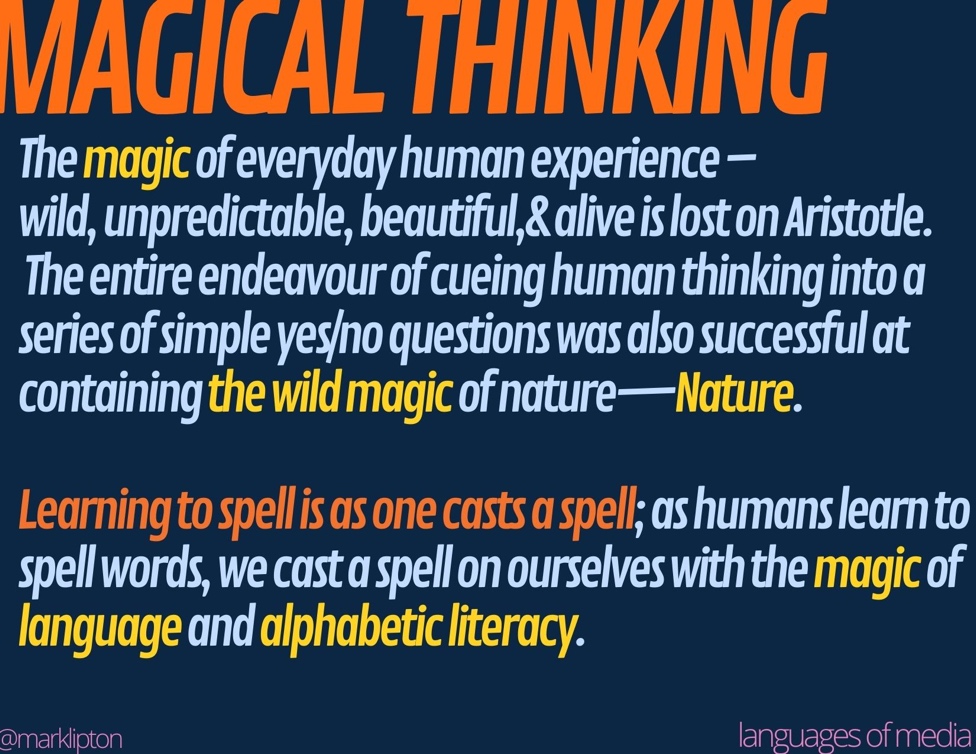

MAGICAL THINKING

When you learn to spell words, it is as if you also learn to cast a spell on yourself with the magic of language and alphabetic literacy. Humans trick themselves with words. The written word is not merely an echo of a speaking voice. It is another kind of voice altogether, a conjurer’s trick of the first order.

Aristotelian thinking may have been valuable for developments in literacy and its impact on human cognition. Today, however, non-Aristotelian thinking is ALSO a way of thinking; Artist thinkers; children-thinkers; twitter thinkers; who know how many kinds and ways of thinking occur in all sentient things living?

THEREFORE

I justify my TRANSACTIONAL world view with non-Aristotelian thinking. By following this line of thinking, which is more in line with scientific thinking, I acknowledge that classifications are human-made and not natural. That words do something in our imaginations that make us believe in the binary logic of objective vs subjective. In fact, all phenomena, all experience is, in one way or another, subjective. Yes, facts are real. Facts are forms of evidence that can be verified. Nonetheless, don’t confuse the fact with the words used to describe the fact.

To review: three fundamental premises of TRANSACTIONALISM, first noted in 1933 by Alfred Korzybski, resist Aristotelian thinking. The premises are:

1. We live in two worlds: words & things (non-words); map vs territory.

2. Words don’t have meanings, people do; the word is not the thing.

3. Language reflects & conditions our thinking & behaviour.

Changing how we use language can change our patterns of thought & behavior. I oppose Aristotle’s THREE laws and prefer a different set of principles. Though not exactly opposite to each of Aristotle’s laws, the principles of General Semantics are Korzybski’s attempts to understand how language and logic and better reflect the characteristics of reality.

1. NON-IDENTITY: A IS NOT A

2. NON-ALLNESS: A IS NOT ALL A

3. SELF-REFLEXIVENESS: ABSTRACTS OF ABSTRACTS OF ABSTRACTS

Characteristics of language work to trick the human mind into confusion the real world with the human-make symbolic worlds. By relying on the power of metaphors to create symbolic worlds, our language habits often cause trouble with our thinking and subsequent actions.

To understand how, let’s take a moment to consider how humans live in both real and symbolic worlds; these symbolic worlds rely on language and other literary, visual, technical, etc., codes and conventions to stimulate a conception of the world. What are the metaphors that guide your perceptions of the world?

METAPHORS TO LIVE BY:SIMILE, METAPHOR, METONYM, SYNECDOCHE

|

simile – comparison using “like” or “as;” metaphor –comparisons (without words like or as), simultaneous, synchronic time; metonym –what happens before or after, diachronic time; synecdoche –a kind of metonym, a part that stands for a whole. |

SIMILE VS. METAPHOR

Many people have trouble distinguishing between simile and metaphor. A glance at their Latin and Greek roots offers a simple way of telling these two closely related figures of speech apart.

Simile comes from the Latin word similis (meaning “similar, like”), which seems fitting, since the comparison indicated by a simile will typically contain the words as or like.

Metaphor, on the other hand, comes from the Greek word metapherein (“to transfer”), which is also fitting, since a metaphor is used in place of something. “My love is like a red, red rose” is a simile, and “love is a rose” is a metaphor.

METAPHOR

A figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them (as in drowning in money) broadly: figurative language— compare SIMILE.

SYNECDOCHE VS. METONYMY

Like many terms used in rhetoric, both synecdoche and metonymy derive from Greek. The syn– in synecdoche means “with, along with” (much like as in synonym) and ekdochē means “sense, interpretation.” Metonymy combines the Greek meta (“among, with, after” the same root found in metaphor) with onyma, meaning “name” or “word.”

Metonymy is when something is used to represent something related to it. Synecdoche is when a part of something is used to refer to the whole.

METONYMY

A figure of speech consisting of the use of the name of one thing for that of another of which it is an attribute or with which it is associated (such as “crown” in “lands belonging to the crown”).

Metonymy refers to the use of the name of one thing to represent something related to it, such as crown to represent “king or queen.” If someone says “a bunch of suits were in the elevator” the reference is to businesspeople, that is an example of metonymy because you’re using the common wardrobe of executives as shorthand for people in that occupation.

It’s metonymy when you use a person’s name to refer to the works by that person, as when you say, “I had to read Hemingway for a class” when you really mean “I had to read a work by Hemingway for a class.” Another straightforward example is when you use a city’s name to refer to its team, as when you say, “Houston was ahead by six points.”

Some examples are so common that today the “part” is now part of the dictionary definition. For example, the use of press to mean “journalists” dates to the 17th century and occurs in the U.S. First Amendment (“Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press…”). This use attributes journalists with the name of the device used for printing newspapers.

In similar classic examples of metonymy, an occupation is identified by the tools used to carry it out. A sportswriter might say that a team’s bats went into a slump, when the writer really means that the hitters in the lineup went into the slump. Sometimes metonymy is used to make a name catchier than the item it replaces, like when surf and turf, using two rhyming terms that allude to the sea and land, is used for to a dish combining seafood and beef.

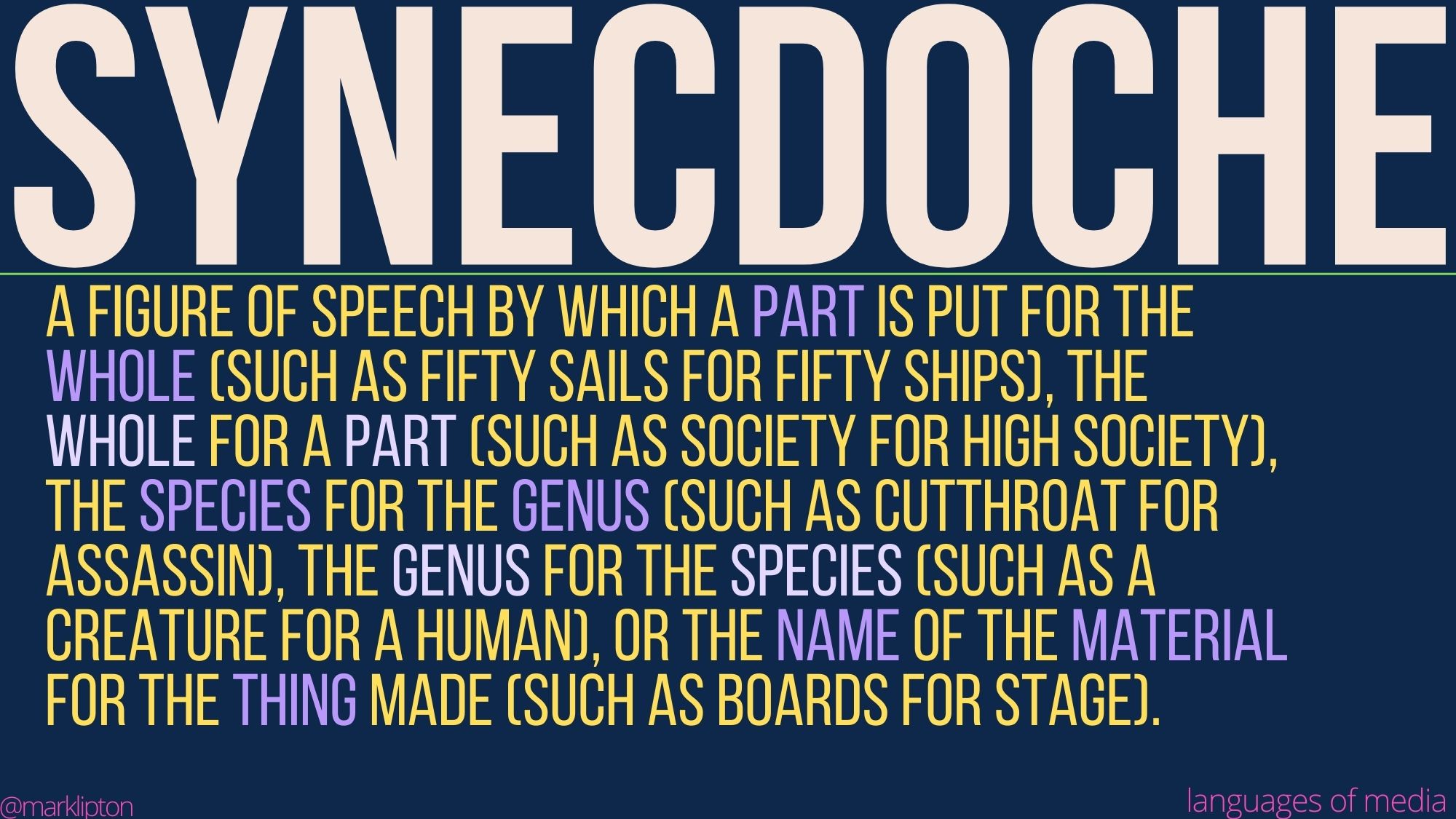

SYNECDOCHE

A figure of speech by which a part is put for the whole (such as fifty sails for fifty ships), the whole for a part (such as society for high society), the species for the genus (such as cutthroat for assassin), the genus for the species (such as a creature for a man), or the name of the material for the thing made (such as boards for stage).

Synecdoche refers to the practice of using a part of something to stand in for the whole thing. Two common examples from slang are the use of wheels to refer to an automobile (“she showed off her new wheels”) or threads to refer to clothing.

A classic example of synecdoche is the use of the term hands to mean “workers” (as in “all hands on deck”), or the noun sails to mean “ships.” Synecdoche is also sometimes used in the names of sports teams (the White Sox, the Blue Jays).

Sources:

“Metaphor.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/metaphor.

“Metonymy.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/metonymy.

“Synecdoche.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam–webster.com/dictionary/synecdoche.

Your empathy and sensory detail allow you to tap into complex situations. The minute details reveal so much. It’s the METONYMIC principle of SYNECDOCHE.

You don’t need to capture the entire kitchen if you have one powerful close-up shot of a kitchen sink. I think this figure of speech is especially impactful when applied to representing a person’s (character’s) desires through moving or still imagery.

What initiates a quest? Human emotions and desires mobilized action. Without our great longings and hungers, life would seem stale and inert. Connect with your emotional vocabulary to mobilize a story (and your life) to fulfilling actions.

Culture, environment, social skills, and language experiences are essential to language development. Active children always try to communicate. When communication becomes symbolic, it becomes clear that language development results from rich social environments. One cannot ignore how learning ecologies, (that is, the sum of the physical and cultural environments, including social interactions and language experiences) are essential to language development.

PLAY

Symbolic communication and learning require forms of play to ignite the imagination. Play is so important, particularly within one’s learning ecology. Play is beneficial in so many ways; play is important in language development, social interactions, creativity, thinking skills, motor abilities, general intelligence, and even brain growth.

Play is fun and can significantly impact one’s mental and emotional growth. Consider play from a variety of perspectives including motor or physical play, social play, constructive play, fantasy play and games with rules.

When you observe others at play, can you recognize these different kinds of play? What descriptive forms of writing help you capture your observations with words?

EVERYTHING’S CONNECTED

Regarded as a key English philosopher, David Hume’s (1711–1776) theory of necessary connection suggests how all ideas are integrated in one way or another. His philosophical works: A Treatise of Human Nature (1739–1740) and Enquiries Concerning Human Understanding (1748), remain widely influential.

Hume concludes that the felt determination of the mind —our awareness of a customary transition from one associated object to another —is the source of our idea of necessary connection. The idea that one object is necessarily connected with another means that the objects always acquire an associative connection in our thought. This association gives rise to the process of making inferences. Having located the role, value, and limits of interference, Hume offers a definition of cause from two distinct points of view:

From the point of view of relevant external impressions, a cause is an object, followed by another, where all the objects like the first are followed by objects like the second. Further, to capture what Hume calls our internal impressions, the definition from this point of view sees a cause as an object followed by another, and whose appearance always conveys the thought to the other. As a result, our human awareness of being is determined by a worldview that necessarily applies systems and customs to our states of knowledge that move from cause to effect.

SYSTEMS

Ervin Laszlo’s (1972) systems theory applies systems, systems methods, and a distinct perspective to model the nature of reality. Knowledge, for example, can be organized into sets of systems and subsystems, building a highly detailed and logical infrastructure. This approach is a holistic way to address and solve important human problems.

Simply put, a general system theory captures holistic patterns across multiple knowledge systems and worldviews. Against standard disciplinary silos, systems theory sees the world organized with an underlying unity. To discover unity, systems theory attempts to mount integrated logical, mathematical, engineering, and philosophical paradigms and frameworks in which physical, technological, biological, social, cognitive, and metaphysical systems can be studied and modeled.

In this light, nature’s distinctive domains, as characterized by the specialized sciences, are contingent expressions or arrangements or projections of an underlying intelligibly ordered reality. If the nature of this underlying unity and the way it conditions phenomenal reality could be understood, it would provide a powerful aid to solving pressing sociological problems and answering deep philosophical questions.

Consider an integrated and multidisciplinary study of systems. Simply put, a system is a cohesive hodgepodge of interconnected and interdependent elements (either natural or human-made). A change in one part of this system impacts other parts or the whole system. In fact, it may be possible to predict these changes as patterns of behaviour.

Systems theory, like most academic disciplines and knowledge networks, is an evolving, dynamic process—not a thing in and of itself. Over time, open systems become increasing complex.

Systems evolve and develop through interactions (transactions) with the physical and media environments and through internal bodily structures of self-reorganization. In many complex systems, the evolving developments cannot be predicted because interacting variables keep changing over time.

Two important points to remember: first, in natural systems, the evolving development of any system is always resource dependent; second, all natural systems tend toward entropy.

Laszlo, E. (1972). Introduction to Systems Philosophy: Toward a New Paradigm of Contemporary Thought. Gordon & Breach. pp. 8-10, 18-21.

LANGUAGE AS COMPLEX SYSTEM

Theories of language try to explain the nature of human language in terms of basic underlying principles. Swiss scholar Ferdinand de Saussure is generally considered the “father of linguistics” (gosh, what a colonial & patriarchal metaphor—sorry about that) because he was the first person who used term “linguistics.”

de Saussure’s ideas on structure in language laid the foundation for 20th century linguistic sciences. In fact, his main book, Course in General Linguistics (1916), made up of lecture notes compiled by his students, is the starting point of 20th century structural linguistics.

As other scholars of time studies specific languages, de Saussure designed and applied a science of studying language in general that got people thinking about features shared among all languages and the overall role of language in human affairs. In other words, de Saussure believed the structure of linguistic systems could impact human actions and behaviours.

de Saussure insisted language, itself, was a social phenomenon. As a structured system, language can be viewed synchronically (as it exists at any particular time) and diachronically (as it changes in the course of time). de Saussure formalized basic principles of and methods for the study of language.

SENSE OF TIME

MONOCHRONIC VS POLYCHRONIC CULTURES

Time is a constant variable in scientific discourse. The expanding map of 20th century ‘progress’ required more than a science of linguistics to understand the world. Cultural anthropologists often situated research about other cultures within their own construct of time.

Monochronic cultures like to do just one thing at a time. They value a certain orderliness and sense of there being an appropriate time and place for everything. They do not value interruptions.

Polychronic cultures like to do multiple things at the same time. A manager’s office in a polychronic culture typically has an open door, a ringing phone and a meeting all going on at the same time.

SYNCHRONOUS vs DIACHRONIC TIME

Synchronic (no past or future; range of things happening simultaneously) vs.

Diachronic (made explicit through our grammar; the horizontal axis – linear)

Cultural anthropologist Edward T. Hall explains monochronic versus polychronic; diachronic (sequential) versus synchronic (metonymic) cultures. These terms explain the cultural differences in perceiving and valuing time. Polychronic cultures do not regard multitasking to be more productive (productivity is not a measure of success). Polychronic and synchronic cultures value relationships more than schedules and do no adhere to strict timetables. Synchronically oriented people are comfortable handling multiple tasks simultaneously and shifting priorities, primarily based on the relationships with the people involved.

Edward T. Hall. (1959) The Silent Language & (1976) Beyond Culture.

PARADIGM & SYNTAGM

Paradigm & Syntagm are two Principles of Representation. Our thoughts can be defined by “paradigms” or conceptual worldviews that consist of formal theories, classic experiments, and trusted methods. Scientists typically accept a prevailing paradigm and try to extend its scope by establishing (or failing to establish) more precise measures and standards.

However, our thinking can be arrested or shocked when new phenomena and experiences transform our understanding of the world. Within the context of “scientific paradigms” – prevailing theories are maintained (like Newton’s theory of mechanics) until an accumulation of failures, anomalies or other difficulties trigger a crisis that can only be resolved by a revolution that replaces the old paradigm with a new one (from Newton to theories of quantum physics and relativity).

The terms paradigm and syntagm emerge from linguistic discourse to understand how our conceptual worldviews are structured, ordered and contained. To understand how human symbolic systems (like language as well as film, television, and other remediated messages) or ‘signs’ impact human affairs, the principles and methods of how sign systems related to one another help direct our analysis and understanding.

Consider how the terms paradigm & syntagm can be used to describe complex language systems as well as other media and sensory rich systems. Paradigmatic relationships are about substitution. Syntagmatic relationships are about positioning.

PARADIGM

A philosophical or theoretical framework of any kind, example, pattern.

A paradigmatic relationship describes how an individual sign may be replaced by another. Paradigmatic relationships are associative—at various levels of abstraction (there is a paradigm and there are paradigms or set/s of items). For example, the alphabet contains twenty-six letters; all letters are part of the alphabet paradigm. In addition, paradigmatic relationships suggest the process of selecting some letters over others; a traditional menu, with categories of food items illustrates a collection of paradigmatic relationships; that is, items of the same group represent ‘a paradigm’ so there is a paradigm of appetizers, a paradigm of main courses, a paradigm of desserts—each paradigm offers choice.

SYNTAGM

A connected or orderly system with harmonious arrangement of parts or elements. Syntagm is closely related to syntactics, a branch of semiotics that deals with the formal relations between signs or expressions in abstraction from their signification (meaning) and their interpreters (meaning-maker).

A syntagmatic relationship is one where signs occur in sequence or parallel and operate together to create meaning. Syntagmatic relationships are often governed by strict rules, such as spelling and grammar. The sequential nature of language means that linguistic signs have syntagmatic relationships. For example, the letters in a word have syntagmatic relationships with one another, as do the words in a sentence.

The implications of more abstract syntagmatic signs such as fashion, art, or news produce more abstract social meanings. The way we seek and understand the world is often based on an abstract set of agreed-up on conventions and code. The social codes are often POLYSEMIC (codes with multiple meanings) or OPEN to a range of possible meanings. Looking at the example of the traditional menu—meal courses have a sequential (syntagmatic) relationship.

Daniel Chandler’s online book Semiotics for Beginners reviews semiotic theories, terms, and applications. Refer to Chandler for additional semiotic knowledge.

RESOURCE

Chandler, Daniel. Semiotics for Beginners, Paradigms and Syntagms.

<http://visual-memory.co.uk/daniel/Documents/S4B/sem03.html>.

PARADIGM SHIFTS

An assessment of the history and philosophy of science clarifies that individual scientists are never able to create or plan paradigm shifts. Thomas Kuhn’s (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is foremost a work of history; it is not an instructive text on creating paradigm shifts. It is not possible to provide guidelines that produce these intellectual revolutions—extraordinary discovery is not a set or prescribed procedure. A paradigm shift is not a planned activity.

Paradigm shifts are more like perceptual hitches or the acquisition of transformative threshold concepts. Like, say you put on a new pair of glasses and suddenly—the way you see the world is completely different and forever changed.

In knowledge networks and disciplinary empires, paradigm shifts are an out of scholarly and scientific effort within the current (dominant) paradigm that produces data that cannot be accounted for within the current paradigm. In fact, this effort (often) produces ‘failure’ and as a result, new knowledge is uncovered—hence a paradigm shift, i.e., the adoption of a new paradigm.

In fact, Kuhn says a discovery that could induce a paradigm shift often comes from unexpected places—happy accidents. For Kuhn, you do not need a formal background in a particular field of science to produce a result that necessitates a paradigm shift in that field. That means, hey, you could experience the happy accident that leads to a cure for CoVid-19 or other such human problems. Happy accidents are examples of learning from failure.

SEMIOTICS

Do you know this word? Semiotics was de Saussure’s name for the science of sign systems. Signs. Like stop signs. Also including abstract meaningful ideas. A study of mind. A study of self. A study of the material and evanescent sparks the make our worlds meaningful.

Semiotics is a branch of intellectual thought begins at a time when linguists, across a wide degree of specificity in subject: from simplest morpheme (the smallest meaningful unit in a language) to intercultural, intersectional, symbols (including utterances, language, thought and action) jump to meaningful contributions to all subsequent philosophy. Simply put, ongoing attention to language and meaning is a skill across the disciplines.

No need to dig deep, yet. This science requires a particular skill in hand and evidence of your practice, prior to meaningful learning. This skill, simply, asks for your attention.

Your attention please.

Media Attributions

- PG13

- three laws