10 10: REALITY CHECK

REALITY CHECK

Jerome Bruner’s “Life as Narrative” (2004) points to Peter Winch’s 1958 proclamation on the veracity and validity of knowledge; Bruner writes:

it is not so evident in the human sciences or human affairs how to specify criteria by which to judge the rightness of any theory or model, especially a folk theory like an account of “my life.” All verifications criteria trunk slippery, and we surely cannot judge rightness by narrative adequacy alone. A rousing tale of a life is not necessarily a “right” account (694).

Here’s my grandmother again. As an oral storyteller, she knew how to improvise. She implicitly understood how improvising creates strong connections. If she knew you loved the colour green, she’d find a way to work that into her story. Are you wearing a hat? My grandmother would start by looking at your hat and unfold into a complicated narrative that—somehow in the end, returned to your hat. She loved to exaggerate every detail. In her sunlight, weaving a tale about our day I might recognize small embellishments.

“Hey, that’s not what happened,” my young voice might raise from my corner. “Phaa,” she’s spit. “Du zalst nisht lozn dem ams bakumen in di veg fun a gute dertseylung.” Yiddish—a completely oral language, can only be written phonetically. My sounds never capture the melody and humour of a native Yiddish speaker.

As I write out these words, I utter sounds cursed by my assimilated-Canadian accent. I didn’t know what my grandmother was saying when she was in her prime, sharing a story. If I persisted, “that wasn’t how it really happened,” someone would eventually repeat, “Don’t let the truth get in the way of a good story.”

The upshot of this lesson crystalized as I practiced my own stories. Stories are specific. Stories invite images, visuals and pictures. Stories evoke a particular time and place. With specific and descriptive language about small details, stories conjure mood, color, sound, texture, taste and other visceral and sensory responses. With specificity, stories suggest worlds with the power to engage the minds of others. The specificity of an experience helps access universal sentiments or insights. It’s the small things that make a world. The devil’s in the details.

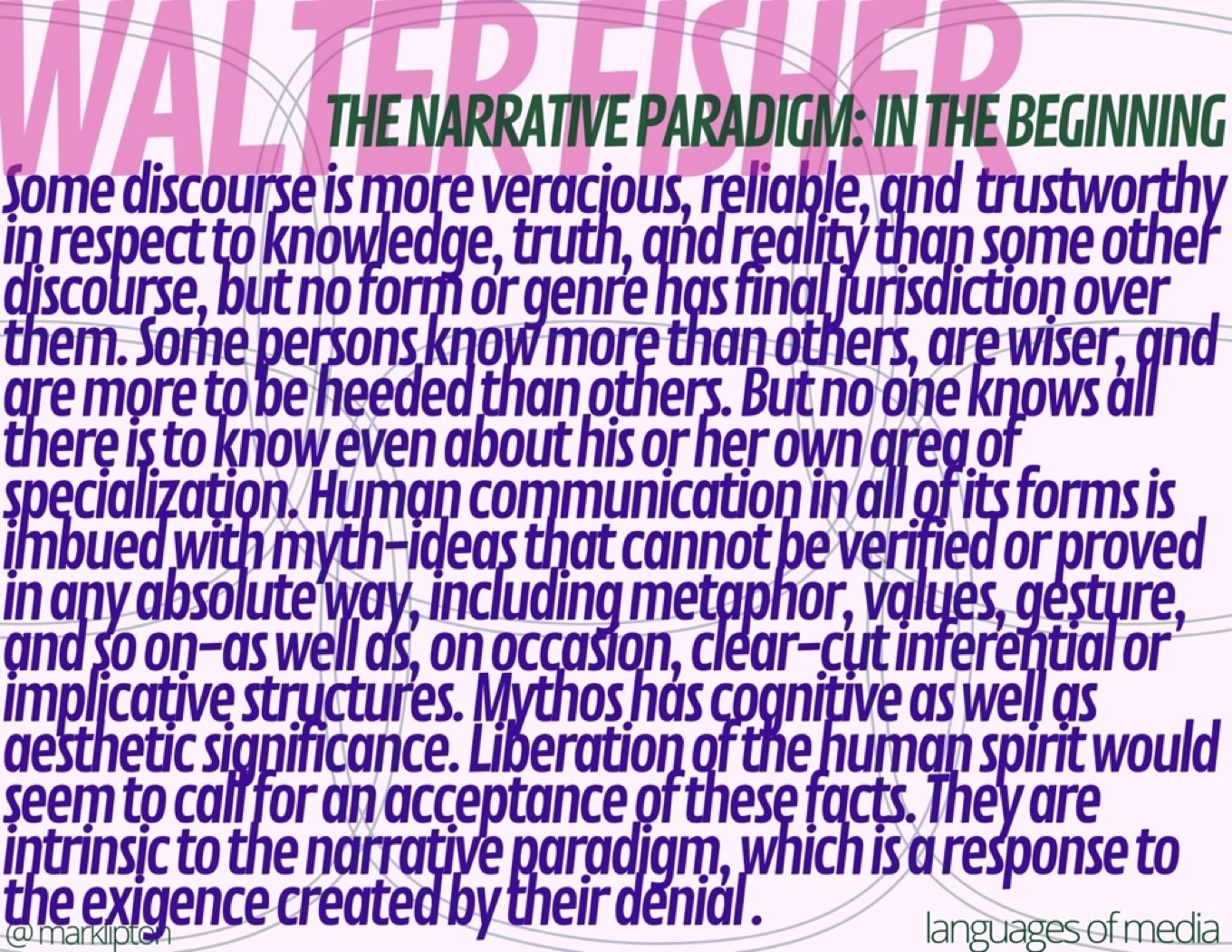

READWalter Fisher’s “The Narrative Paradigm: In the Beginning.” Jerome Bruner’s “Life as Narrative.” 2004.

SUGGESTED READINGSMattingly, Cheryl, Nancy C. Lutkehaus, and C. J. Throop. “Bruner’s Search for Meaning: A Conversation between Psychology and Anthropology.” Ethos 36.1, 2008. Mos, Leendert. “Jerome Bruner: Language, Culture, Self.” Canadian Psychology 44.1, 2003. |

ON THE LEVEL?

“Stop telling such outlandish tales” is a passage from a story my mum could recite at will, to my great delight. “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street” was Theodor Seuss Geisel’s first children’s book. Dr. Seuss makes me smile. I relished his embellishments and musical style. Can you hear it?

Marco, keep your eyelids up

And see what you can see.

Poor Marco, I thought as a child. No one will ever give him the benefit of doubt. The name of the main character echoed mine and every time I heard my mother’s voice seize Seuss’s prosody my mood lifted. Elated.

When I moved to New York City in the late 1980s, my mother gave me a new, clean edition of our shared memories. Inside the cover I see her script, “Mulberry Street is on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. When you find it, promise you’ll call home and tell me what you see.”

In Manhattan’s Little Italy, Mulberry Street is below the standard street grid New York City is known for (I lived at 77th&3rd; A&9th; 23rd&10th), where zig zagging roads crisscross with no apparent order. I think it was mid-September—I clearly remember the dreadful humidity. Every movement dragged in moist air. Trashcan odors hung like Christmas lights.

I crossed an Avenue and suddenly, I walked into a street festival. The street was filled with Manhattanites of all shapes and sizes. Vendors in carnival trailers seduced a slow-moving crowd: whack-a-mole, ring toss, hot pretzels with yellow mustard, a mini-donut machine and homemade gelato. My frozen pistachio cream had real pistachios! Served in a small paper cup, I scooped the melting delight with a wooden spoon as I worked my way through the hot crowd.

At the corner, the festival ended. Another few steps and I returned to regular traffic. As I am apt to do, I made my way to the corner so I could shimmy my back against the dark brick building, looking for north. Looking up, the street sign astonished my blinking eyes and disoriented head; I dropped my gelato! I was on Mulberry Street. I later learned it was the Feast of San Gennaro. That night I called home, super excited, mum was going to love this.

“On my god, mum, you won’t believe it. You won’t believe what happened today!”

My mother knew a good story was coming. “I was walking downtown, and I stumbled upon Mulberry Street.”

Yes, Yes. Mom wanted details, “so, what did you see?”

I wanted to build her anticipation. Mimicking her methods, like all those times she recited this tale of Mulberry Street, was not easy. My story sounded “outlandish,” like “turning minnows into whales.” When my story ended my mom retorted, “is that all?” I smiled into the phone, recounting:

I’ve looked and I’ve looked

And I’ve kept careful track.

But all that I’ve noticed,

Except my own feet

Was a horse and a wagon on Mulberry Street.

Now that is a true story. In this section, as I write to you, the imaginary readers/learners, I clutter my prose with English idioms. As a figure of speech, idioms are one of the most perplexing—often the meanings are deep beneath the surface. An idiom is a word or group of words with a figurative meaning not easily deduced from its literal meaning. Confounding, I know. In recalling the oral wisdom from my mostly matriarchal family, I match the beauty of Yiddish (for me) with a classic idiom from literature.

Miguel de Cervantes published Don Quixote in the early 17th century. I learned the ‘experts’ consider this ‘masterpiece of literature’ the first modern novel. During that time, theatre and the play genre were more common and accessible for greater numbers of people.

Nonetheless, Cervantes hit the genre tipping point; the novel’s main character is enamored with the notion of chivalry, and spends his time fighting with windmills. He imagines windmills as giants and “tilting at windmills” was Don Quixote’s exercise in futility. Tilting at windmills means fighting imaginary enemies.

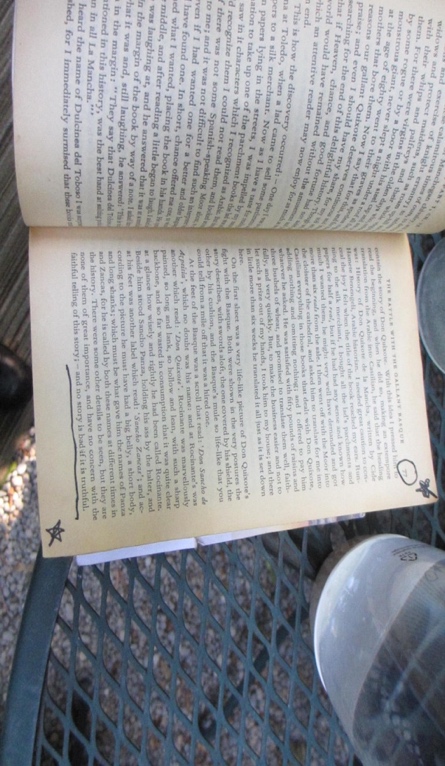

I remember rereading last summer and underlining words that spoke to my grandmother’s sagacity. Don’t tell a librarian because from their point of view marginalia is destructive —I snapped a pic of the page to further provoke my memory.

I see two hand drawn pentangles in the top and bottom corners of the page; the page number is circled: 77; the underlined last few words on the page are spoken by Don Quixote’s companion Sancho Panza: “—and no story is bad if it is truthful.”

From my grandmother’s oral wisdom to Cervantes’ literary classic Don Quixote: the lines drawn around truth or fiction blur. When you try to adjust your perspective on the world, you are trying to analyze how ideas are perceived by others who don’t share own same assumptions or backgrounds. People respond to a story not so much because it is true, but because they find it meaningful.