4 04: LEISURE IS HARD WORK

LEISURE IS HARD WORK

RESPONSE

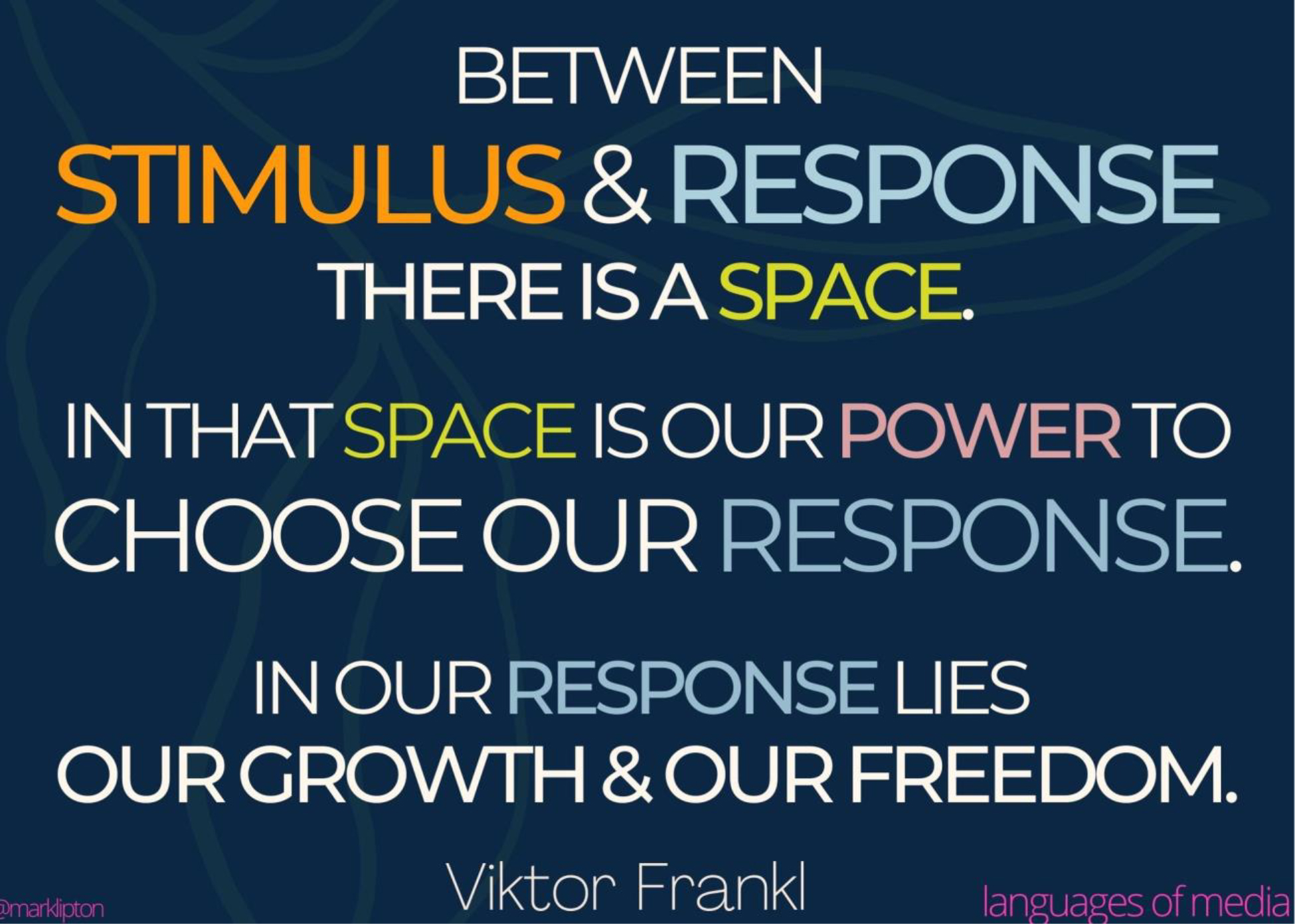

When your sense preceptors identify a sign, you CHOOSE what happens next. Viktor Frankl survived Nazi concentration camps by choosing to believe there was still good in the world.

Your response reveals a great deal about YOU. Words don’t mean, people mean; the action of reacting/responding tells the world a story about you. I’m not talking about any sign or text or thing. We can all ‘see’ the same sign and discover meaning in entirely different ways.

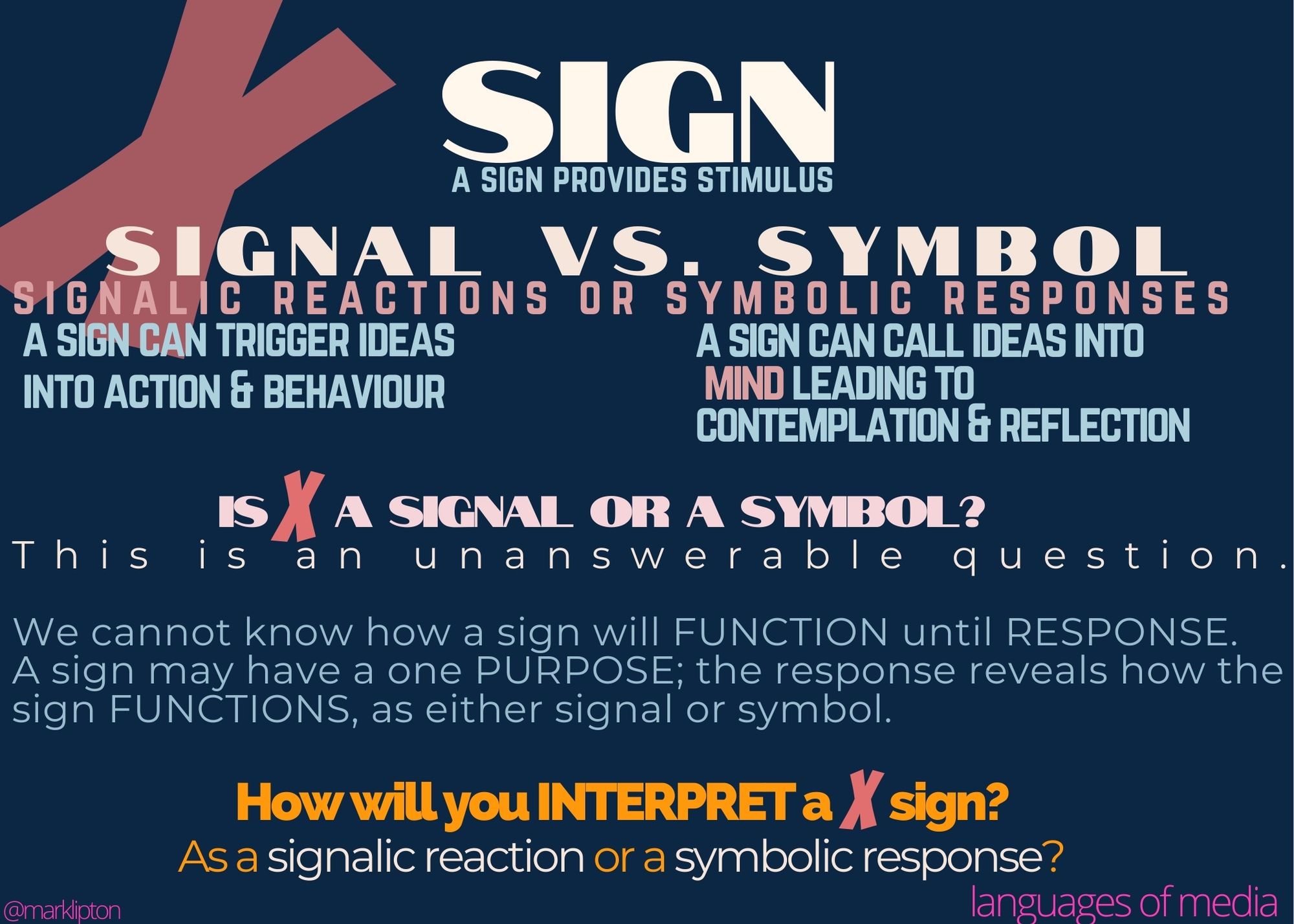

I am not describing any change or difference in the sign itself. Instead, it is essential to recognize a simple dichotomy. There is a significant difference between two types or modes of response. I name these signalic responses vs. symbolic responses. Sentient creatures make meaning of the world in two ways; there are two kinds of [pb_glossary id=”906“]signification[/pb_glossary]. Click, run.

Psychologists have discovered a number of mental shortcuts people rely on when making meaning from everyday life. Decision making, based on automatic judgments, is a shortcut where additional information is ignored in favour of the easy response or action. This tendency to respond mechanically to a single piece of information in a situation is the controlled, automatic, signalic response. I like to think of signals and symbols because I find these are how the information is perceived; as one signal leading to an automatic action -click, run; or as a symbol, invoking reflection and analytic thinking -hmm.

SIGNALS

SIGNALIC RESPONSES

Sign calls ideas into behaviour and results in action. This action is usually fixed, rapid, and instantaneous. Signals function as a kind of a behavioural command for respondents. Behavioural centers process the stimulus provided by a sign, and subsequent action is triggered, usually based on past experiences.

Signalic responses are conditioned responses, like Pavlov’s dogs (bell = salivate). Signalic responses are extremely powerful (sensory-motor learning) in humans, often left over from pre-linguistic experiences. Animals use signs to REACT to things (as signals), providing an evolutionary advantage because one significant element conjures up the whole experience.

SYMBOLS

SYMBOLIC RESPONSES

Sign calls ideas into mind, resulting in reflection, that is, delayed reactions, involving thought. Sign functions to call up an idea that doesn’t necessarily call up a particular behaviour stimulus. Memory and thought centers in the brain evokes a complex notion; the idea is a name for something in the world that humans use; signs REFER to things (as symbols).

Once you choose how to respond; once you become CONSCIOUS of how you respond—your language and thinking demonstrate SYMBOLIC work.

You walk into an office building and need to find the twenty-first floor. You walk toward a bank of elevators. How do you know what to do? How do you call or request an elevator?

Next to an elevator is what appears to be a button. This possible button itself is neither a signal nor a symbol. A thing, in and of itself, can motivate or constrain your actions. And these are degrees of change, not direct action/reaction. Most people react to this button <signalic response> because they are often already moving when light goes on, a bell dings; it’s as if the elevator was already there.

Your cell phone is ringing. Before you move a muscle – FREEZE. Are you one of Pavlov’s dogs? The ring, in and of itself, is neither a signal nor a symbol.

Scenario ONE: Phone rings. I immediately pick up phone when it rings and say, “Hello. This is Mark. What can I do for you?” SIGNALIC RESPONSE. If you respond immediately, without thinking, it’s a signal.

Scenario TWO: Phone rings. I look at phone. I say to myself, “Mark, you don’t really want to talk to anyone right now.” Phone continues to ring. I continue to ponder, “who might be calling,” “should I answer?” SYMBOLIC RESPONSE. If I allow myself time; if I halt my body’s tendency to jump toward the phone to answer; if I give myself a moment to think; if I pause, it’s a symbol.

WORDS AS SIGNS

Words are generally considered [pb_glossary id=”902“]symbols[/pb_glossary]. There is no actual or visual connection between the word and its meaning. Words should be symbols.

Words ARE symbols.

However, frequently words function as signals, like commands. LIKE WHEN someone calls out your name & it generates a particular action – you turn around and look . . . word as [pb_glossary id=”908“]signal[/pb_glossary].

SOMETIMES SIGNS FUNCTION AS BOTH SIGNALS & SYMBOLS

Perhaps this example may sound like something that happened to you:

Sometimes, I could be in my room reading, or watching television, or outside riding my bike; my mother will call out my full (and very long) name:

“Moshe Dov Barrel Pesach Labe Lipovitch – Mark Brian Lipton!!!!”

If I drop what I’m doing and yell back, “Ma, I’m here.” This is no big deal. My mother uses her Pavlovian-powers and I turn around or look to her. My response is signalic.

However, sometimes my mother has a ‘tone’ to her call, and I feel something tingle in my stomach. What does this mean? I read or understand my mother’s call of my name as a symbol because this time, I know she’s mad at me, it’s serious, I’M IN BIG TROUBLE (again). My response is symbolic.

Children start using speech sounds signalically to stand for a whole event. At first, the child is not able to categorize, compartmentalize or differentiate among the various elements of the event. In this case, a certain part of an experience becomes memorable through repetition and eventually comes to represent whole experience/event.

My first word as a baby was “juicy.” My mother thought I wanted juice. My grandmother thought I was repeating her favourite topic Jews. I kept saying “juicy.” If I was given juice I cried more.

As an infant, I connected the sound “juicy” with this one very memorable experience. I was in the office of my pediatrician Dr. Farber. He just gave me a needle for something, and I cried and cried and cried because something pinched my skin, and my mother was crying, and everything was scary.

A few moments later, I witnessed my mother opening a package of chewing gum. The yellow packaging was shiny, and beneath the yellow paper was shinier, silver paper. My mother gave me a piece of gum. I liked the sweet flavour and the sticky substance that changed when it was in my mouth. My mother said something like, “so you like Juicy Fruit gum? As a baby, I made the sound “juicy” to call up this entire experience. When my mother gave me more Juicy Fruit gum, I continued to say, “juicy, juicy, juicy.” My mother understood me pretty quickly. And we both love chewing gum.

My first word, the sound “juicy” allowed me to conjure up the entire experience of Dr. Farber, needles, shiny things and chewing gum. [Another odd word I remember saying “fancy” somehow stood for driving along University Avenue in Toronto, across the Hospital for Sick Children, the fountains along the boulevard. Fancy=Fountain. Weird.]

Eventually, as children we learn to separate one part from whole; at which point the sign [juicy or fancy] comes to stand for only that part of the experience [gum or fountain]. By about age two, children start to understand that our sounds and other “noises” don’t automatically summon whole event.

|

IT IS IMPORTANT TO KNOW THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SIGNALIC&SYMBOLIC RESPONSES |

SIGNALIC responses are unavoidable; and these can be dangerous if we don’t know the difference. In signalic response, we act in the presence of the sign as we would in the presence of the object; we act without reflecting.

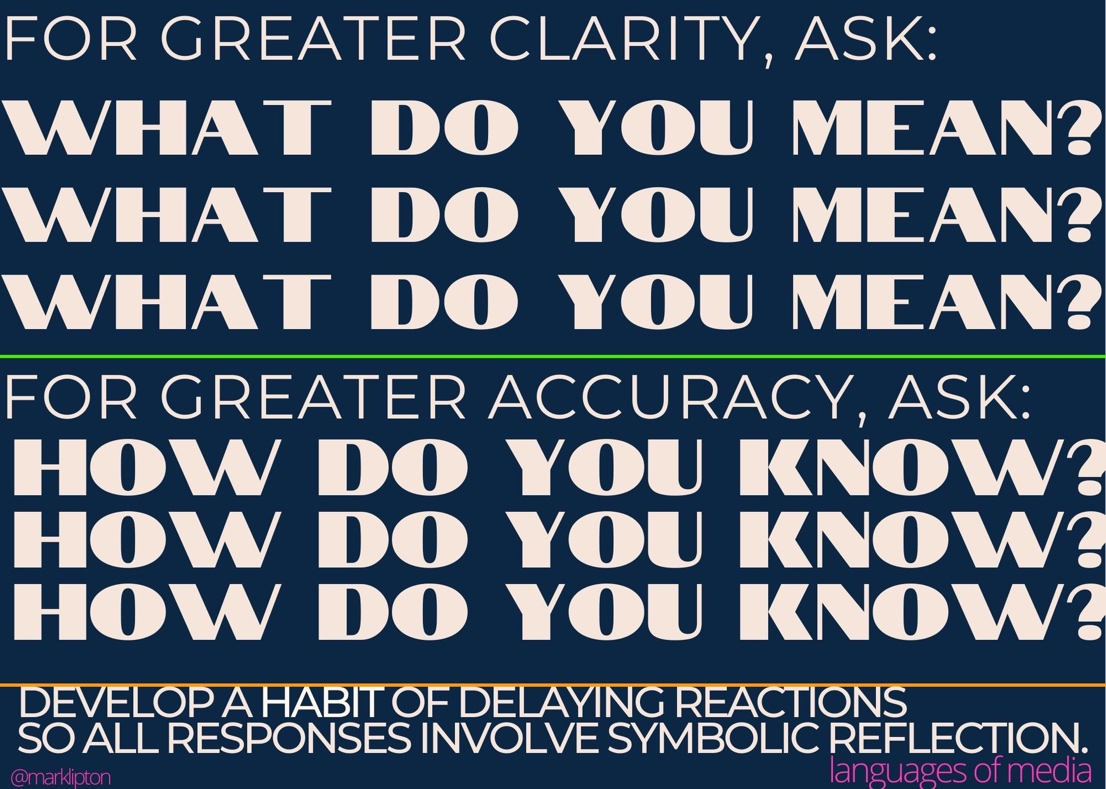

Want to know HOW to turn a SIGNALIC response into SYMBOLIC response?

PAUSE.

Reflecting rather than acting immediately; think before acting. Work to develop habits of delaying reactions. The pause makes your thinking more symbolic and thus your response symbolic.

DELAYED REACTIONS/RESPONSES

Pausing—taking a moment of time, increases the chance that our response will be appropriate to the situation. Often, a delay can be a few seconds and that’s just enough for our thinking to pass from automatic to thoughtful.

This moment in time may mean the difference between behaving like an animal or a human. By developing habits of delaying reaction/response—by pausing and taking a second, we avoid living at the mercy of our emotions, feelings, and instincts. Delaying reaction/response helps us avoid rash decisions or actions we may later regret.

Joe calls Jon a “chicken.” Without thinking, Jon gets upset and takes on a posture of aggressive defensiveness. Jon is ready to start fighting in response to being called the word chicken. Because Jon doesn’t let thought take place, the response is unreasonable.

However, sometime the instantaneous signalic response is most appropriate:

Jane sees a brick falling from building & it’s heading straight towards her friend Joan. Jane yells “Joan! Look out!” Jane saves Joan’s life. What a good friend!

You really are a responsible adult. That means you take responsibility for your actions. Learning to delay reactions is something you actively must choose to do. Time to decide. What guiding principles do you look to when faced with difficult decision making? How are you using media? How is media using you? Let’s find out!

LESIURE IS HARD WORK

Do I need to ask you how many hours a day you spend with media? You probably selected this class because there is something about “media” that triggered your interest. In the last decade I watched media education researchers report how young adults have accelerated media use; for some, media habits require up to seven or eight hours a day. That’s the time required for a fulltime job. What is your fulltime job? What access have you been granted? Do you need to think about “breaking up” with your phone? Are you able to watch one episode of something on Netflix and then, turn the television off—maybe you find it difficult to walk away after watching your program’s cliffhanger? This is not a judgment. This is the current state of the world.

How might you describe your current relationships with media messages? How well do you understand the information and communication technologies? How well do you understand the functions (or invisible consequences) of media’s algorithmic and platformed infrastructures? How do you spend your time? What do you do for fun?

To remain relevant, today’s media tools, like smart phones and laptops, are designed to be very easy to use. Consumers rarely interact with the many layers of complexity removed from the interface. Most users do not possess the expert technical knowledge needed to understand the ideological implications of these complexities. Do you use media for social interactions? Are you successful at using media tools? Do you find these tools easy to use? Do you understand the complexity going on beneath the surface?

Media tools are marked by a deep discrepancy between appearance and capacities. The material and perceptible form and its trivial interfaces fail to offer any sense of impact or assumption embedded in the programming, production, languages, platforms, connectivity, as well as conflicting ideological agencies bundled into every device.

When playing with media functions as the main form of human interaction, the use of today’s tools perpetuates a productive epistemology of ignorance. How to we begin to address the impact of media and its uses? Media tools may create spaces of play, contingency, and potentiality—however, simultaneously, critical discourse is limited to content and interface. It is hard to be critical when you have no idea how something works.

Nonetheless, people around the world with access to media tools are remixing, appropriating, and sampling texts to create new forms of expression. Kirsten Drotner (2008) suggests “young people’s digital practices promote the formation of competencies that are absolutely vital to their future, in an economic, social, and cultural sense” (167). Drotner considers the relationship between these digital practices and your learning and education.

READ

Drotner, Kirsten. (2008). Leisure Is Hard Work: Digital Practices and Future Competencies. In David Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, Identity, & Digital Media. (Pp. 167–184). The John D. And Catherine T. Macarthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Media educators have long called for and understood the educational uses of tools that produce media messages. You may already use media production tools for leisure or pleasure or for the sake of playing with tools in and of itself. This course asks you to engage in this technical play with an intention of applying critical thinking and symbolic work.

Here is the challenge: use the tools of production to critique, explore, examine, and analyze media texts of all kinds. Digital storytelling, with its potential for layering multiple modes of expression (words, images, sound, movement), invites you to play with media tools as creator. YOU have the POWER!

Usually, you are situated within media messages and media systems as a passive consumer. In fact, despite the amounts of time we spend with our digital devices, as Darrin Barney (2005) explains,

| for some people access to the internet is a source of empowerment, autonomy, and agency, for many it simply means connection to a technological infrastructure in relation to which they remain significantly disadvantaged and powerless (pp. 155-156). |

As we learn about media, you are encouraged to work with and through media to redress this imbalance; an objective is to seek greater understanding of the terms “empowerment,” autonomy” and “agency.”

These terms are most clearly visible within the context of Canada’s digital divide, between those who have access to media tools and those without.

Barney, Darin. (2005). Communication Technology.

QUESTION

Do you know how much time you dedicate to personal and social media uses? Consider how you spend your day? Track your media use. What helps you pay attention? What digital skills have you mastered?

WHAT IS MEDIA LITERACY?

Media literacy is the process of making sense of or decoding media. It allows us to critically view media. It also allows us to evaluate the role that media play in our lives. When someone is media literate, he or she interprets the ways in which media have been manipulated to get the viewer to think a certain way. By understanding the ways that media try to exploit their viewers, we gain the power to resist the media’s influence.

When becoming media literate, we must develop awareness that people create all media. Those people have many motivations and constraints that they must use to spread their ideas. As people who are media literate, we learn to examine the ideas and the values that are portrayed in the media product.

Everyone uses interpretive processes when viewing media. Media literacy simply allows the viewer to be critical and careful when confronted with media. Opportunities and challenges of digital media within an educational context engaged through media provide a framework for examining the operations of pedagogy and learning within a complex web of attitudes and cultural practices.

The ramifications and assumptions of media pedagogy that look more closely at the underlying claims of difference, identity, and non-hierarchical teaching and knowledge suggest the need for new approaches to critical practice and interpretation.

As a result, I ask you explore your media uses and habits as empowering. How do you see media and its component tools as enabling your understandings and applications of communication, creativity, critique, persuasion, performance, and education?

GRAMMARS

First: let me share this provocative statement:

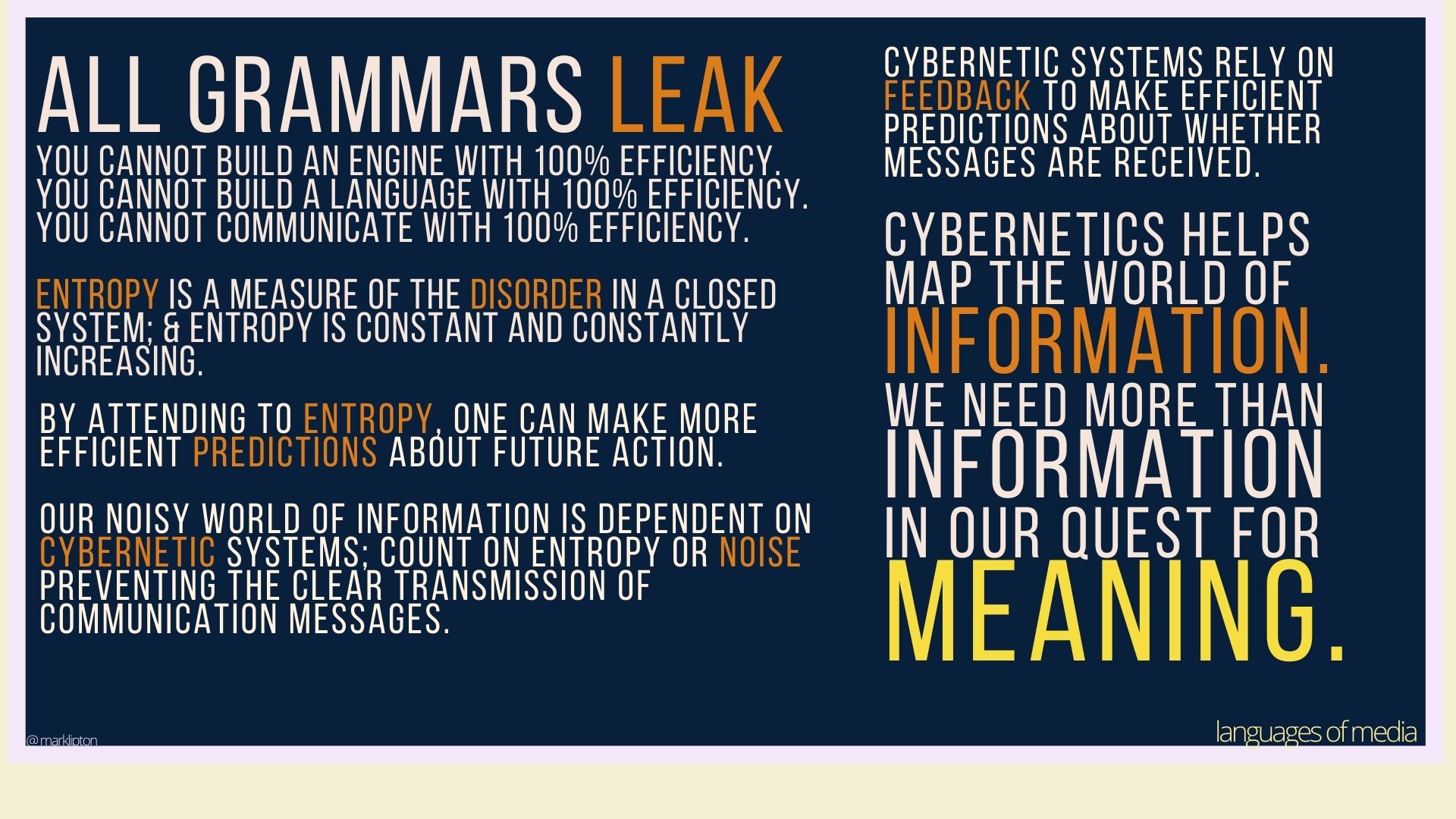

“ALL GRAMMARS LEAK.”

Did he say leak?

I find grammar study tedious and painful, and I hate formal rules and stuff like clauses —and what the heck is a GERUND?

I do believe grammar is important. Grammar gives language the characteristic of combinations and recombination. Gramma gives language users the ability to combine. Grammar mostly exists naturally, in our minds.

I am not sending you out to learn any new rules. When you learned to speak, you learn to distinguish the sounds of our language from random sounds. The smallest possible unit of sound that we learn to distinguish is call a phoneme. Vowels and consonants are phonemes. Vowels and consonants are sounds we can combine to make words. Then we get into things like morphemes, the smallest unit of meaning; and then prefixes and suffixes. Oh my!

The study of meaning is specifically called semantics. Simply put, grammar and semantics are sets of rules for combining phonemes and morphemes and blocks of language to communication information and make meaning.

ENTROPY: ALL GRAMMARS LEAK

OK—but what’s leaking? Simply put, despite language and its grammatical rules, it is impossible to transmit 100% of a message. Grammars can help, but when people receive this message, they bring their own past experiences and worldviews to your message.

VISIBLE EVIDENCE

I’m going to show you a text. And before you tell me what you think, or what you feel, I ask you to identify the evidence. What are you looking at? What are your sense preceptors sensing? Learning to pay attention is an important skill.

PRINCIPLES OF PERCEPTION

All perception (and all experience) is a transaction. The nature of a transaction is such that the two parties involved (two people, or a person and an object) are both shaped by their relationship with each other. Neither party is ever passive nor simply acted on by the other. Reality is knowable only through our transactions with it. Our habitual use of language tends to obscure the transactional nature of experience.

For the most part, we do not get our perceptions from the things out there. Our perceptions come from within us. We see things not as they are, but as we are. We are not born perceiving. We learn to perceive and not to perceive.

What we perceive is always a function of the structure of our nervous systems. The structure of the organism (for example, the human eye) limits what we can perceive.

What we perceive is also a function of the extensions of our nervous systems, these include the instruments through which we look at reality (for example, I require corrective lenses). Our instruments not only structure what we see but inevitably alter it.

What we perceive is always a function of our past experiences. From our past experiences, we build up an assumptive world, that is, a set of (more or less) unconscious beliefs about the way things are and all experience is then filtered through these assumptions.

While the specific content of one’s assumptive world is always unique (since no two people ever have the same experiences), some general assumptions are shared by the members of a culture. In our culture, some of these perceptual constancies are the assumption of rectilinearity, the assumption of size constancy, the correlation of brightness with nearness and dimness with distance, and the assumption that in cases of relative movement, the frame (background or larger area) is stationary, and the foreground (or smaller area) is moving.

All perception is an attempt to establish a predictable continuity in life to reduce uncertainty by imposing familiar structures on it. Every perception involves both the past and the future. Perceptions are predictions.

What we perceive is a function of the context in which the stimulus is presented. What we perceive is a function of the context the perceiver finds him/herself in.

What we perceive is a function of our needs, purposes, and values.

We do not change our perceptions based on verbal information alone, but through acting on our perceptions and encountering hitches which require us to modify our perceptions.

Since our perceptions come from within us and are based on our past experiences, everyone perceives reality in a unique way.

What we perceive is to a large extent a function of the coding systems (e.g., language) we have internalized.

What we perceive is to a large extent culturally determined.

WE ARE THE MOST ILLUSIONED PEOPLE ON EARTH

VISUAL & TECHNICAL GRAMMARS

What I call grammar, really, refers to a set of guidelines to facilitate effective and efficient communication. In this sense, all media and all languages have grammar. Much of this is already familiar given the huge amounts of media we consumer each day. The goal, in tinkering with this media grammar is for you to get some idea what goes into the creation of daily global communication messages. The degree of expertise and technical skills is mostly invisible unless you’ve had an opportunity to play with the tools. As you do, I expect there will be challenges along the way. Hopefully, each challenge will be an opportunity for you to learn, build resiliency, and communication skills.

ATTENTION

Hey, LOOK HERE! What are symbols for you that trigger ATTENTION of mind, focus of vision, still and calm throughout the body. Everything currently at hand is open as material for the semiotician. What are you looking at? What are you listening to—right now?

Human sense receptors, i.e., our senses—are pretty much the only way humans can make sense/meaning of the world. Are you aware all of your senses are WORKING for you—ALL THE TIME. These senses know no time.

ATTENTION – and I mean SUSTAINED ATTENTION is a skill that, when exercised and practiced, is consistently improving. This is the skill that, with ongoing exercise and practice, promises to enhance your abilities for all other learning skills.

ATTENTION requires practice. The more you practice, the more you sense—see, experience your world.

| ATTENTION REQUIRES PRACTICE. |

THE MYTHS OF MULTITASKING

Simply put, multitasking (1) Limits your focus of attention; and (2) Limits your ability to retain knowledge (information retention).

Multitasking means a “switch of focus” resulting in cognitive overload (limiting learning and the learning brain by) dividing cognitive attention, which results in an increased limit in the ability to retain all necessary and important information.

See Monochronic vs polychronic cultures.

Multi- or dual-task conditions were proven to reduce declarative memory. ALSO: areas of the brain that are involved in the learning process with specific focus on declarative memory and habit-learning memory.

Declarative memory is having the ability to know a piece of information off the top of one’s head; it is forever ingrained into one’s memory and can be recited upon command.

Habit-learning memory is different; it doesn’t rely on understanding the concept, just the action or process involved. (Foerde et al. 11778).

CALCULATING THE COST OF MULTITASKING

For some tasks, such as identifying the gender of a face, and then switching to identifying the facial expression, the switch only takes only about 200 milliseconds. But even this small cost can reduce productivity by 40 percent if you try to study while watching a movie.

COGNITIVE LOAD

Ideally, instruction should be reviewed/received in a way that reduces the processing of information that does not contribute to learning (extraneous load) and increases cognitive processing that contributes to learning (germane load).

A way for learners to effectively manage extraneous load is by designing learning and reading plans that control the flow of information. How do your time management skills modulate you viewing/listening/learning strategies? Do your learning strategies mediate the relationship between extraneous load and germane load? How so?

The negative correlation between extraneous load and germane load can be mitigated when learners engage in thoughtfully planned (i.e., specific) strategies to better understand the content.

|

YOU CAN OVERCOME the CHALLENGES of DISTRACTION, MULTITASKING AND EXTRANEOUS COGNITIVE PROCESSING |

HOW TO PAY ATTENTION

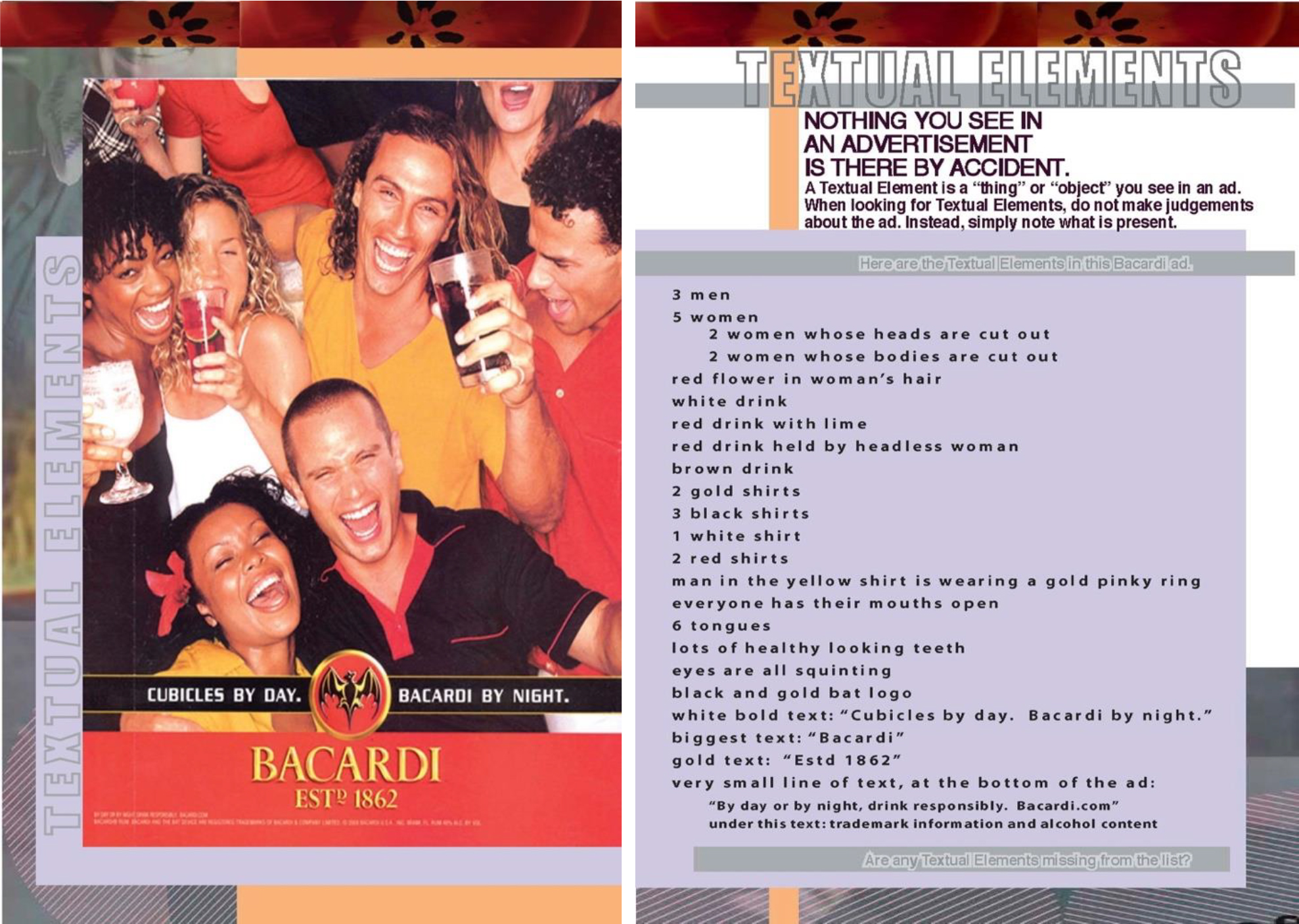

To begin, once you have selected the text that you want to decode you need to look at it carefully. There are many things going on in every media message, but most people don’t look carefully enough. To begin any decoding, you need to be a keen observer.

Nothing you see in media is there by accident. For example, advertisers spend a great deal of money for each ad to make sure that the ad you see is exactly what they want you to see.

Make a list of all the things that you see in the text. Call this your list of textual elements—that is, a list of all the things you can observe. This requires great skill at description.

VISUAL AND MEDIA LITERACIES

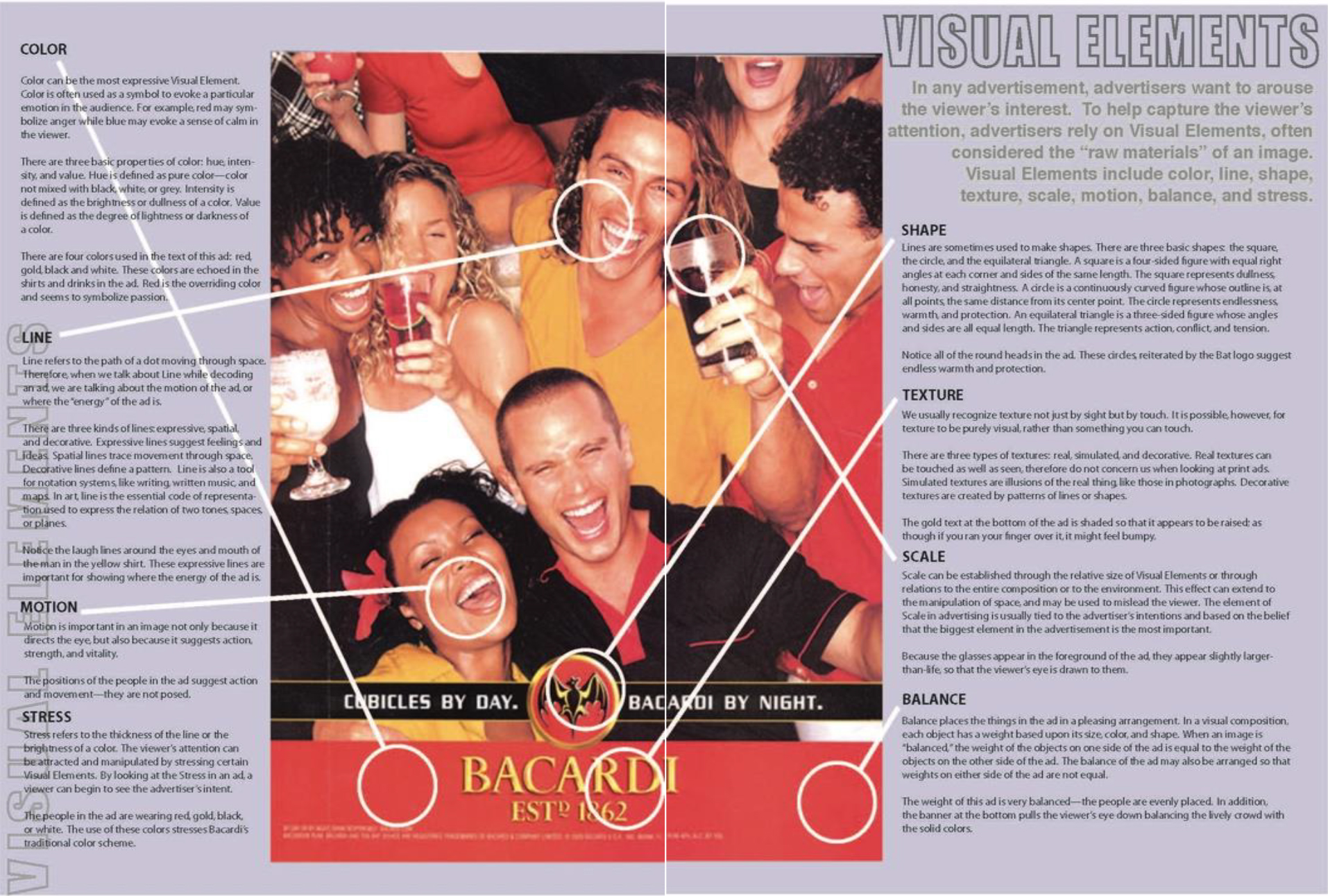

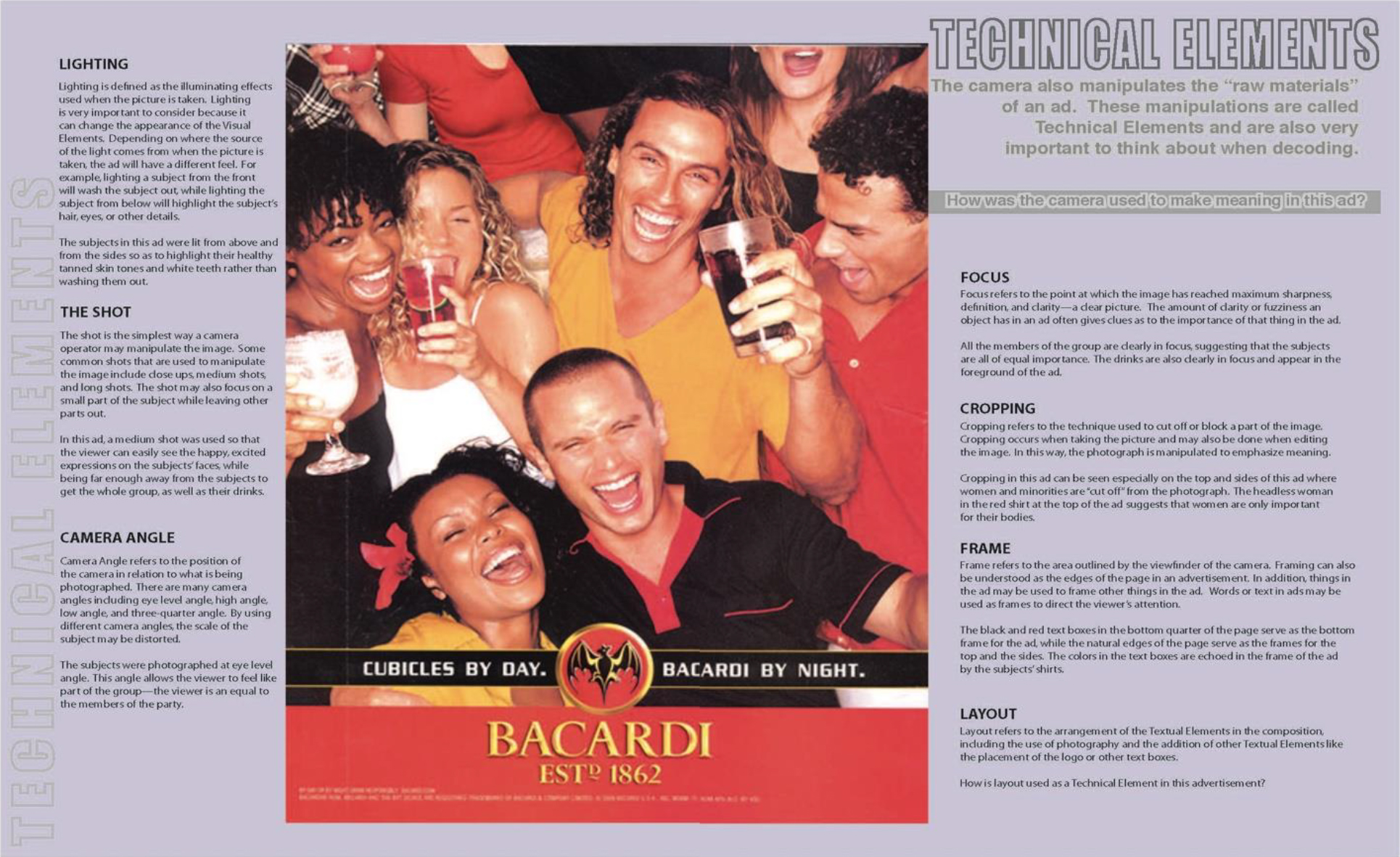

Second, you need to consider the visual and technical elements. In any media message, creators’ want to arouse the viewer’s interest. To help capture your attention creators rely on visual elements such as colour, texture, and balance. In addition to these visual elements, creators rely on sophisticated technology like cameras that further enhance and manipulate what you see. Technical elements of the camera like lighting, camera angles, focus and framing also help capture your attention and help creators ensure that the message you receive is the message they intend. Keep close track of these lists of elements because they represent the fruits of your observation and description skills.

VISUAL ELEMENTS

TECHNICAL ELEMENTS

FROM ATTENTION TO ANALYSIS

Once you have completed lists of the things you see, you must try to account for why these things are included in the selected media message. Remember, nothing you see is there by accident. To determine why these elements may be included, what questions do you ask yourself?

QUESTIONS to focus

YOUR media LITERACIES

1. Who is communicating and what is their point of view? Why are they sending this message?

Every media message is communicated for a reason — to entertain, to inform, and usually to persuade. Yet the basic motive behind most media programs is profit through the sale of advertising space and sponsorships.

2. What are the intended or underlying purposes and whose point of view is behind the message?

Behind every message is a purpose and point of view. The advertiser’s purpose is more direct than a program producer, though both may seek to entertain. Understanding their purposes and knowing WHOSE point of view is being expressed and WHY is crucial to being media literate.

Every media message is communicated for a reason—to entertain, to inform and usually to persuade. Yet the basic motive for most media is profit. To assess the motives of any form of media you must understand that every message has a purpose and a point of view. By considering the point of view behind the message you will often uncover its underlying purposes and intentions. For example, if you understand that every tobacco advertisement is designed with the tobacco company’s point of view then you will understand that the intention of its messages is to sell cigarettes. Understanding an ad’s purposes and knowing whose point of view is expressed is crucial to the process of decoding.

3. Who owns, profits from, and pays for media messages?

Media messages are owned. They are designed to yield results, provide profits, and pay for themselves. All news and entertainment programming, including film and television, try to increase their audiences to attract advertising dollars. Understanding the profit motive is key to analyzing media messages.

Media messages are owned. They are designed to yield results, provide profits, and pay for themselves. The implications of ownership are enormous. Consider the example of Kraft Foods. Did you know that Philip Morris owns Kraft? Knowing that this company has lied to the public about tobacco so that it could increase its profits should make you cautious about their other products. Understanding the profit motive is key to analyzing media messages.

4. Who are the target audiences for media messages and what meanings are made?

All messages are made with some sense of the people receiving them. People filter these messages based on their beliefs, values, attitudes, behaviors, and past experiences. Identifying the target audience for a given message and knowing how its audience may interpret it will help make you more media literate.

All media try to increase their audiences to attract more money. All messages are made with some sense of the people receiving them. People understand these messages based on their beliefs, values, attitudes, behaviours, and past experiences. Identifying the target audience for a given message and knowing how its audience may interpret it will provide you information about the intended message and its goals.

5. How are media messages communicated?

Messages are communicated with elements like sound, video, text, and photography. But most messages are enhanced using visual and technical elements– through camera angles, special effects, editing, or music. Analyzing how these features are used in any given message is critical to understanding how that message attempts to persuade, entertain, or inform.

Messages are communicated through sound, video, text, and photography. But most messages are enhanced by visual and technical elements—camera angles, special effects, editing or music. These elements enhance the emotional impact of any media message. Analyzing how these features are used in any given message is critical to understanding how that message attempts to persuade its audience.

6. What is NOT being said and why?

Because messages are limited in both time and purpose, rarely are all the details provided.

Identifying the issues, topics, and perspectives that are NOT included can often reveal a great deal about the purposes of media messages. In fact, this may be the most significant question that can uncover answers to the other questions.

Because messages are limited in both time and purpose, rarely are all the details provided.

Identifying the issues, topics and perspectives that are not included can often reveal a great deal about the purposes of media messages. In fact, this may be the most significant part of finding answers to the other questions.

7. Is there consistency both within and across media?

Do the political slant, tone, local/national/international perspective, and depth of coverage change across media or messages? Can you escape your filter bubble and fact-check? Because media messages tell only part of the story and different media have unique production features, it helps to evaluate multiple messages on the same issue. This allows you to identify multiple points of view, some of which may be missing in any single message or medium.

Decoding any media message is like being a detective. Keeping in mind the preceding questions, you must be on the lookout for clues. When you find them, you must try to figure out what they mean. Then you must piece them all together so that you can reconstruct what exactly the media message is trying to get you (or mislead you) into believing.

NOT ALL MEANINGS ARE EQUAL

These questions along with the concepts of media languages, grammars, and literacies can help you begin a thorough and detailed semiotic analysis. One way to view semiotic analysis is as the method for seeing though and understanding the manipulative means and ideological consequences of media messages; another perspective invites your attention as an active search for meaning. Keep in mind that your meanings reveal a great deal about you as the meaning maker. With our principles of perception, the polysemy or polysemic nature of media messages, and they means by which people perceive their worlds, any analysis can lead to a range of possible meanings. There are no single correct answers. However, your meanings are communicated in language, structured by grammar and logic. Not all meanings are equal.

Some messages make stronger or more persuasive arguments. Put another way, your interpretation of a media message is the story you make from that message. Since media messages can mean a number of things and since it’s people that make messages meaningful, it very much depends on who is engaged in the semiotic analysis—in the creation of this responsive story. How you structure an argument or a story can make your meaning more impactful or your assessment more valuable.

DESCRIPTIVE VS. REFLECTIVE WRITING

Let’s put grammar aside; because the strength or value of an argument depends on the EVIDENCE or FACTS presented – the visible evidence. Herein lies a crucial distinction between descriptive language and reflective language; the former may function as fact, the latter is only opinion. Whether argument or story, the strength of the message relies on the descriptive details.

We can all watch the same commercial and each viewer discovers a different meaning. The point of relying on semiotic analysis is to make a strong ARGUMENT about WHY your meaning is more accurate.

I may disagree with your opinions, but I WILL DEFEND TO THE DEATH, your right to your opinion.

SOME OPINIONS ARE BETTER THAN OTHERS

& some opinions ARE BETTER than others because the direct link to EVIDENCE makes one opinion more PERSUASIVE than another.

Media Attributions

- between stimulus

- mark lipton

- bacardi 01

- bacardi 02

- bacardi 03

the art, science, or profession of teaching