5 05: STORIES BODIES TELL

STORIES BODIES TELL

I want to take this opportunity to introduce you to some of my friends.

MEET MARSHA P. JOHNSON

Her name was Marsha P. Johnson.

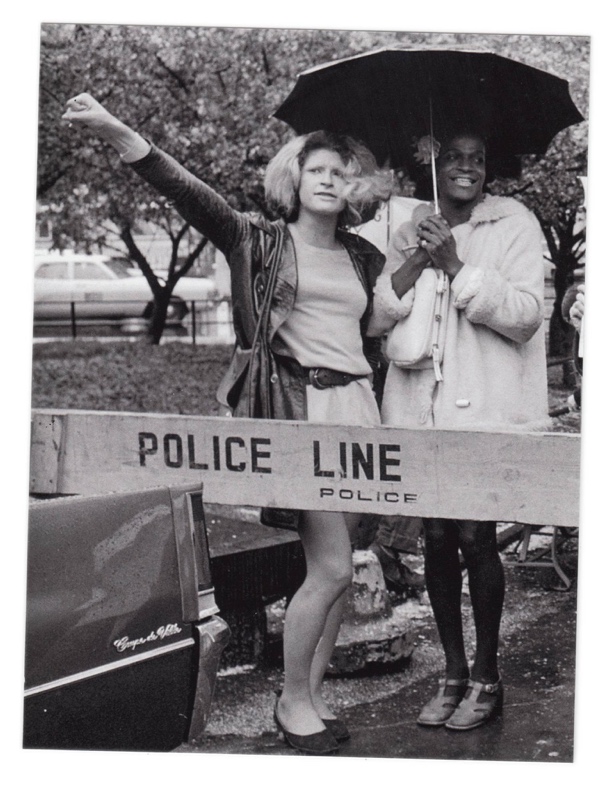

Marsha P. Johnson was an activist, drag performer, sex worker, and fixture of queer street life in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. She was a central figure in a gay liberation movement, energized by the 1969 police raid on the Stonewall Inn.

Many say it was Marsha who threw the first brick!

Pride exists because of a woman.

Pride exists because of a black woman.

Pride exists because of a black trans woman.

Pride exists because of a black trans woman who was a sex worker.

Pride exists because of a black, bisexual, trans woman, a sex worker, threw a brick at a cop.

Pride exists because of a black, bisexual, trans woman, a sex worker, threw a brick at a cop—and started a riot against the state.

Don’t let experiences of LGBTQ+ Pride be washed in the rainbow of capitalism and unabashed racism. Many white queers are unaware of their privilege. I was, until I met Marsh on the streets of New York City. Her kindness tied to a sharp tongue arrested me instantly; she had no trouble reading my ignorant innocence at twenty-years-old. I told her my name.

She told me to stand proud.

To celebrate PRIDE, I support queer people of color, trans women, and queer sex workers.

TRANSGENDER PIONEER & ACTIVIST

MARSHA P. JOHNSON

1945-1992

Marsha P. Johnson in Greenwich Village in 1988. After graduating from high school in Elizabeth, N.J., she moved to New York with $15 and a bag of clothes.

Image credit: Randy Wicker

RESOURCE

<https://marshap.org/about-mpji/>.

The Marsha P. Johnson Institute (MPJI) protects and defends the human rights of BLACK transgender people. By organizing, advocating, and creating an intentional community to promote collective power, MPJI seeks to heal our communities while developing models for transformative leadership.

We intend to reclaim Marsha P. Johnson and our relationship as BLACK trans people to her life and legacy. It is in our reclaiming of Marsha that we give ourselves permission to reclaim autonomy to our minds, our bodies, and our futures. We were founded both as a response to the murders of BLACK trans women & women of color and how that is connected to our exclusion from social justice, namely racial, gender, and reproductive justice, as well as gun violence.

SEX AND GENDER

The very moment babies are born, their assigned sex is announced. For some of us, this assignment of sex as male or female matches our subjective experience (“gender”). Gender is far more complicated than “boys” and “girls,” but not too complicated for learners of any age. All people have a gender, express that gender each day and are affected by gender stereotypes.

For some of us, the assigned sex at birth creates confusion and/or dissonance. The assignment doesn’t match our internal gender experience. Gender does not follow Aristotelian login; gender is not a binary. Instead, gender is a spectrum with masculine at one end, feminine at the other and androgynous or genderqueer somewhere in the middle.

Given different points on the spectrum, it’s no surprise that gender identity (one’s subjective experience of their own gender) and gender presentation (one’s external performance of their gender) can be open and fluid.

GENDER IDENTITY is how you identify and see yourself. Everyone gets to decide their gender identity for themselves. You may identify as a girl or a boy. Suppose you don’t feel like a boy or a girl. In that case, you might identify as agender, genderqueer, nonbinary or just as a person. You have a right to identify how you want, and your identity should be respected.

SEX assigned at birth is a medical label. If your gender identity matches the sex assigned to you at birth, then you are CISGENDER. For example, if you identify as a girl and you were assigned female at birth, then you are CISGENDER. People whose gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth may be TRANSGENDER.

Regardless of our GENDER IDENTITY and SEX assigned at birth, people express their GENDER in various ways. This includes the way that we talk, our mannerisms, how we interact with others, our clothing, accessories, hairstyles, activities we enjoy and much more.

Avoid the reliance on a person’s GENDER EXPRESSION to guess their GENDER IDENTITY. Circumvent stereotypes and misconceptions; stereotypic language can unintentionally inflame prejudice, discrimination, and violence.

A guide from the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) Foundation, the educational arm of the nation’s largest lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) civil rights organization, is intended for learners like you—committed to telling the stories of transgender people accurately and humanely, from appropriate word usage to context that reflects the reality of their lived experience.

TRANSGENDER

A transgender person (not transgendered) is someone whose sex assigned at birth is different from who they know they are on the inside. It includes people who have medically transitioned to align their internal knowledge of their gender with their physical presentation. Transgender also includes people who have not or will not medically transition as well as non-binary or gender-expansive people who do not exclusively identify as male or female. Preferred usage includes “transgender people,” “transgender person,” “transgender woman,” “transgender man,” “trans people,” “trans person,” “trans woman,” “trans man,” “non-binary people” or “non-binary person.” People may also describe their gender with other terms; whenever possible, defer to how the individual chooses to identify.

Know the difference between “gender identity,” “gender expression,” and “sexual orientation.” Gender identity is one’s internal concept of self as male, female, a blend of both, and/or neither. It includes how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves. One’s gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth. For many transgender people, their birth-assigned sex and their own sense of gender identity do not match.

Gender expression refers to the external appearance of one’s gender identity, usually expressed through behavior, clothing, haircut, or voice. These may or may not conform to socially defined behaviors and characteristics typically associated with being either masculine or feminine.

Sexual orientation refers to emotional, romantic, sexual, and relational attraction to someone else, whether you’re gay, lesbian, bisexual, straight, or use another word to accurately describe your identity. Refrain from using “sexual preference,” “lifestyle,” “homosexuality,” or “heterosexuality.” For example, some people are transgender and straight, while others are transgender and gay.

Refrain from contrasting trans men and women with “real” or “biological” men and women. Not only is this a false comparison, but this language also erases transgender identities and can contribute to the inaccurate perception that transgender people are deceptive or less than equal, when, in fact, they are authentic and courageous.

PRONOUNS

Many people, including international students, performers/writers, trans people, and others might go by a name in daily life that is different from their legal name. The pronouns someone indicates are not necessarily indicative of their gender identity. In this course, we seek to refer to people by the names that they go by. Support self-identification and respect the names and pronouns each of us go by.

Pronouns can be a way to affirm someone’s gender identity, but they can also be unrelated to a person’s identity. They are simply a public way in which people are referred to, in place of their name, like he or she or they or ze or something else. Additionally, how you identify in terms of your gender, race, class, sexuality, religion, and dis/ability, among all aspects of your identity, is your choice whether to disclose (for example, should it come up in conversation about our experiences) and should be self-identified, not presumed or imposed.

I’ve had folks kindly ask which pronouns I use to respect my chosen pronouns— I find the question very complicated given my history and experiences. I prefer he/they/t(he)y. This means I vacillate between the pronouns he/him and they/them and choose to use both. There is no single way to be nonbinary. Nonbinary people, for the most part, have such varied gender expressions and self-presentations and often neither match cisnormative expectations. People can identify as nonbinary and self-present in many ways. That’s why it’s best to never assume (ass | u | me) anyone’s pronouns, to respectfully ask how they wish to identify, and share your own if you choose to do so (and feel safe).

I promise to do my best to address and refer to all learners with their chosen pronouns; and support all learners as we negotiate our ways of seeing. If I make a mistake, I ask you to let me know so I can apologize for my error and correct any missteps.

TRANSITION

Transition is a process some transgender people undergo when they decide to live as the gender with which they identify, rather than the sex assigned at birth. A transgender person transitioning is not becoming a man or a woman; they are living openly —embracing their true gender. Transitioning can include medical components such as hormone therapy and surgery. However, not every transition involves medical interventions. Many people cannot pursue medical interventions because of cost or health. Recognize that transitioning is a very personal process, and everyone has a right to privacy.

Transitioning is not about surgery (thought it may). The process of transitioning involves affirming one’s gender identity through social means, like the social process of using different names and/or resisting the pronouns she or he. Transitioning may also involve legal actions, like the official procedures for changing one’s name on a driver’s license, passport, and other legal documents. Changing one’s identity documents is often a complex, time-consuming, and sometimes costly process. Many places refuse transgender people from receiving revised identity documents that reflect their gender identity.

NAME CHANGES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH

The University has formal processes that enable students to update their name and email address to better reflect their identity. For students without a legal name change, you can submit the <Change of Given Name(s) and/or Gender Identity Form>. Instructions on how to submit are found directly in the form, as well as information on where this change will be reflected. For students with a legal name change, you can submit the <Change of Legal Name Request Form>. Regardless of one’s legal name or gender marker on identification documents, use the names and pronouns as communicated by the individual.

Transgender people are extraordinarily diverse. They come from every type of community and represent every race and ethnicity. They pursue a wide range of professions, participate in a variety of religious traditions, and play important roles in families, including as parents. Because prejudice and discrimination are so common, transgender people are more likely than cisgender (i.e., non-transgender) people to live in poverty or experience homelessness. This makes them especially vulnerable to violence and contact with law enforcement.

Unfortunately, when reporting on violence against transgender people, media messages may misgender transgender people, disrespecting their identities, causing pain to a grieving transgender community, and reinforcing the stigma at the center of anti-trans violence. This also happens when law enforcement agencies or local officials make public statements. Deadnaming is the word used when transgender identities are disrespected, like when names assigned at birth are repeated or published.

In 2020, Human Rights Campaign (HRC) tracked at least 44 violent deaths of transgender or gender non-conforming people. This number excludes unreported cases and serious attacks that did not end in death.

CIS PRIVILEGE

CISGENDER MALE/FEMALE are the words that describe people with a gender identity that matches their sex assignment—cisgender folks match the dominant cultural names of sex and gender. As a result, cis gender people experience the benefits of belonging to dominant cultural messages. Participating and reinforcing dominant cultural messages comes with a degree of privilege.

Let’s imagine a scenario: Victor identifies as a boy. At birth, doctors’ sex assignment was male. As he grew up, Victor’s gender expressions maintained masculine definitions in his culture. Picture the people in Victor’s life who perceive his gender expressions as male.

OKAY—I want to change the scenario slightly.

You are Victor.

Are your expressions of gender ever questioned?

Do you worry about daily expressions of gender and your culture’s gender stereotypes?

Is it possible to move through the world without ever thinking about gender?

Is it possible to move through the world without feeling limited because of gender identity and gender expressions?

When sex assignment, gender identity and gender expression are aligned, the CIS GENDER identity experience benefits from CIS PRIVILEGE. Do you or people in your world experience CIS PRIVILEGE? How? In what ways does CIS PRIVILEGE manifest in your life?

READ

Singal, Jesse. 2018. When Children Say They’re Trans, The Atlantic, July/Aug Issue.

<https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/07/when-a-child-says-shes-trans/561749/>.

QUESTIONS

Is your gender identity easy to define? How do you identify today? Does your gender identity match the sex you were assigned at birth?

Have you been given sufficient space to explore your gender expressions? Have you given others space for gender exploration? What are some ways you are expressing your gender today? How might this change on a different day? What are some ways you break gender stereotypes? How have you encouraged others to freely express their gender? How? What did you do?

How does Singal frame the issue of transitioning? What is missing from Singal’s analysis?

Do you know or have you met any TRANSGENDER people? What changes can you make to make your life and world more inclusive of transgender people?

RESOURCE

Human Rights Campaign. (2020). Brief Guide to Getting Transgender Coverage Rights.

<https://www.hrc.org/resources/reporting-about-transgender-people-read-this>.

University of Guelph LGBTQ2IA+ Campus & Community Resources

<https://www.uoguelph.ca/studentexperience/LGBTQ2IA-Resources>.

ARCH GUELPH provides anti-oppressive, sex-positive, inclusive care, treatment, and prevention services in the area of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted blood-borne infections through innovative health promotion strategies and community engagement.

<https://archguelph.ca/>.

OUT ON THE SHELF is a community group that hosts events for LGBTQ+ people in the Guelph community. <http://www.outontheshelf.com/>

The University of Guelph has many groups who provide resources, support, and social opportunities for LGBTQ2IA+ people:

- Guelph Queer Equality builds capacity through events and by providing resources.

- The Guelph Resource Centre for Gender Empowerment and Diversity is a feminist groups and community space dedicated to promoting diversity and equity through education, advocacy, resource provision, skill-building, outreach, and community building.

- Queer and Trans People of Colour works to build community amongst black, Indigenous, and people of colour who are queer and transgender.

- Queer Christian Community is supported by the Ecumenical Campus Ministry for people who wish to explore the intersection of Christian faith and their LGBTQ+ identities.

- OVC Pride Veterinary Community provides safer spaces for the LGBTQ+ community within OVC, to help raise awareness of the LGBTQ+ community within the veterinary profession.

- EngiQueers Guelphpromotes and advocate for the inclusion of LGBTQ+ students and their allies.

- OUTlineprovides confidential support and resources for people with questions relating to sexual orientation and gender identity, online chat, and other in-person support programs.

- Student Help and Advocacy Centre is a student run advocacy and referral centre that provides a safe space for students to ask questions and get information.

BEAR WITNESS

What does it mean “to bear witness?” How might you bear witness to this urgent topic?

INTERSECTIONALITY: MEET KIMBERLÉ CRENSHAW

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term INTERSECTIONALITY 30 years ago. At first, INTERSECTIONALITY was a relatively obscure legal concept. In the years since the idea of INTERSECTIONALITY is heralded as one of the most important contributions to feminist scholarship.

To simplify this topic, I define INTERSECTIONALITY as the interactions of multiple identities and subsequent experiences of exclusion and subordination. INTERSECTIONALITY

refers to the interaction between and among one’s lived categories of DIFFERENCE (like gender and race) in individual lives, social practices, institutional arrangements and cultural ideologies and the outcomes of these transactions in terms of POWER.

I cannot deny how the term, like most academic jargon, is not precise. I see how INTERSECTIONALITY helps to understand individual experiences and functions in my attempts to theorize IDENTITIES. I continue my efforts to understand how this concept functions within social structures, cultural discourse, and ideology. Crenshaw conceptualizes INTERSECTIONALITY as a CROSSROAD, and her metaphor supports my knowledge and use of the term.

INTERSECTIONALITY extends feminist thought by exploring how categories of race, class, and gender are intertwined and mutually constitutive. This gives a central position to such questions as:

How is race is gendered?

How is gender racialized?

How are gender and race connected to social class?

How can identity categories resist the status quo and structures of POWER?

How can identity categories transform POWER structures and the world?

Now more than ever, it’s important to look boldly at the reality of race and gender bias; it’s important to recognize & understand how the two often combine to create more harm. The term INTERSECTIONALITY describes this phenomenon; as Crenshaw says, if you are standing in a path of multiple forms of exclusion, you are likely to get hit by both.

Kimberlé Crenshaw calls on us to bear witness to this reality and speak up for victims of prejudice.

| if you are standing in a path of multiple forms of exclusion you are likely to get hit by both. |

VIDEO SPOTLIGHT on KIMBERLÉ CRENSHAW

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. The Urgency of Intersectionality. TEDTalks. 2016. (18:15)

<https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_inter

sectionality?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare>.

READ

Jane Coaston’s The Intersectionality Wars, 2019.

<https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/5/20/18542843/intersectionality-conservatism-law-race-gender-discrimination>.

QUESTIONS

How do you understand INTERSECTIONALITY?

How is the term useful to you?

What is a FEMINIST?

Do you consider yourself a FEMINISM? Why or why not?

Can cis men be FEMINISM?

How do you understand the relationship between FEMINISM and INTERSECTIONALITY?

MEET SYLVIA RIVERA

QUESTIONS

What do you know about LGBTQ+ liberation? What can you tell about Rivera, based on the representation of her in this video? How does Rivera respond to her daily experiences of social exclusion? Do the people’s responses to Rivera surprise you? Why or why not?

How did Rivera’s language and attitude create liberatory spaces within LGBTQ+ communities? What is Rivera demanding? Are you surprised? What do you notice? What triggers your initial response? The film quality? Setting? Sound interference? People? What draws you to those signs? Do you recognize the politics in action? Do you agree or disagree with Rivera? With her approach?

FEMINISM

Summer 2019.

The United States of America celebrated the 100th ANNIVERSARY of the 19th Amendment to its Constitution. The 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote. At the time, many witnessed social media carousing and circulating a list of NINE things WOMEN could not do until 1971. My team and I did our best to fact check the VERACITY of each item on the list.

RESOURCES

NONPARTISIAN FACTCHECKINGSNOPES is a reliable fact-checking website. I check SNOPES to verify information I’ve discovered on the Internet. SNOPES is recognized as a source for validating and/or debunking stories circulating in popular culture.FACTCHECK.ORG Annenberg Public Policy Center hosts this political fact-checker, which monitors the factual accuracy of what is said by major U.S. political actors.FACTCHECKER (Washington Post) A weekly blog from the Washington Post.POLITIFACT.COM The St. Petersburg Times and Congressional Quarterly hosts a fact-checking ‘Truth-O-Meter’ scorecard scrutinizing attacks on political candidates and includes explanations.SNOPES.COM The oldest and largest fact-checking site on the Internet.PUNDITFACT Dedicated to checking the accuracy of claims by pundits, columnists, bloggers, political analysts, hosts and guests of talk shows and other media members. |

FEMINISM IS NOT JUST FOR OTHER WOMEN

Lisa Bialac-Jehle (2016); D. Evon, Snopes, (2019). NINE THINGS WOMEN COULD NOT DO IN 1971. <https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/9-things-women-could-not-do/>.

NINE THINGS WOMEN COULD NOT DO IN 1971

In 1971 a woman could not:

1. OBTAIN CREDIT

When the United States Senate passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in October 1974, banks could no longer discriminate against women applying for credit or credit cards. Before this legislation, women applying for credit cards were asked a barrage of personal questions. They were often required to be accompanied by a man (husband) to co-sign. Even then, women’s credit was assigned lower limits and/or higher rates. Social movements for equal civil rights focused on credit cards when women produced evidence to document the discrimination they faced. In 1974, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act made it illegal to discriminate against someone based on their gender, race, religion, and national origin.

2. WORK WHILE PREGNANT

Although on-the-job sex discrimination was outlawed more than a decade earlier, pregnancy was not legally recognized as a type of sex discrimination. Women working in the United States won the legal protection to become working mothers in October 1978, when Congress enacted the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. No longer could employers deny a woman a job, promotion, higher pay, or any other opportunity — because she was pregnant. Before this, if women revealed a pregnancy, the consequences usually ended with a pink slip (loss of job). Some employers enacted formal policies prohibiting pregnancy outright because female employees were expected to conform to the company’s image. For example, most airlines expected flight attendants to suggest sexual availability to businessman customers; most teachers learned to represent purity and chasteness as expected by school districts.

3. SERVE ON A JURY

Women were excluded from jury service for many reasons. For example, a woman’s primary obligation was to be a caregiver to their children and families. Men believed women to be fragile and required shelter from criminal details, particularly offences involving sex. In 1975, the US Supreme Court ruled in an 8-1 decision that it was constitutionally unacceptable for states to bar women from juries. The ruling argued shifting economic and changing social patterns made it constitutionally unacceptable for states to deny women equal opportunity to serve on juries. Women’s social roles were changing. This ruling recognized women’s growing economic independence and women’s abilities to assess and fight for their legal rights.

4. SERVE IN MILITARY

Since the US Revolutionary War in 1775, women could aid military operations in noncombat positions as support staff, cooks, or nurses. In 1976, the first women were admitted to the United States Military Academy at West Point; other military academies followed. However, women were still restricted from serving in artillery, armour, infantry, and other combat roles. In 2013, the Pentagon’s military sanction against women in combat was reversed when the US military officially lifted the ban. At that time, women made up about 14% of the military’s 1.4 million active members. More than 280,000 women soldiers were on duty in Iraq, Afghanistan or overseas. And some 152 women were killed in these war conflicts.

5. IVY LEAGUE EDUCATION

The Ivy League is comprised of eight universities in the northeastern part of the United States. Yale and Princeton did not accept female students until 1969. Harvard did not admit women until 1977. Brown finally admitted women in 1971. A year later, Dartmouth admitted women. The last all-male school in the Ivy League, Columbia College, became coeducational in 1983. No laws require post-secondary institutions to admit both men and women.

6. TAKE LEGAL ACTION AGAINST WORKPLACE SEXUAL HARASSMENT

No one knew the term SEXUAL HARASSMENT until 1975 when a group of students at Cornell University formed a group called Working Women United. The organization’s activism defined sexual harassment as “the treatment of women workers as sexual objects.” Carmita Wood resigned from her role as an administrative assistant to a professor at Cornell University because she had been physically ill from the pressure of avoiding unwanted sexual advances. Subsequently, she was refused unemployment benefits.

Working Women United quickly grasped the extent of this problem and its habituation beyond the university setting. By 1977, three legal rulings confirmed that a woman could sue her employer for harassment under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (formed in 1965), the federal agency that administers and enforces civil rights laws against workplace discrimination) was responsible for redress and compensation. Carmita Wood became one of the first women in the US to sue her employer because of SEXUAL HARASSMENT.

Extremely litigious, the public battleground these cases defined sexual violence and misconduct. However, it was not until 1986 when The US Supreme Court upheld the claim between Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson. Michelle Vinson, a bank employee, complained about a supervisor who intimidated her into having sex. Like many litigants in pioneering SEXUAL HARASSMENT cases, Michelle Vinson was African American. The success of racial discrimination cases encouraged women of colour to vigorously pursue their rights at work.

7. SPOUSAL RAPE

Spousal rape was not criminalized in all 50 U.S. states until 1993. Most state criminal codes defined rape in ways that explicitly excluded spouses. Before 1979, the criminal code assumed that marriage constituted permanent consent that could not be retracted. This assumption was often paired with the belief that a woman’s past sexual experiences could be used by the defence in a rape case. The first official conviction of spousal rape was in 1979, in Massachusetts, a man who broke into the home of his estranged wife and raped her. Despite this victory, advocates continue to argue against legal loopholes that allow spousal rape to be treated differently than rape.

8. OBTAIN HEALTH INSURANCE at the same monetary rate as men

Women seeking individual health insurance typically pay higher premiums because gender rating is commonplace among American health insurance companies. The National Women’s Law Center argues the industry practice of gender ratings means women spend one billion dollars more than men on health insurance premiums each year. In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) sought to remove this practice; sex discrimination was not prohibited in health insurance until 2010. Under the health care overhaul, the ban started in 2014. There are still sitting elected officials in the US who publicly feel women don’t mind paying more money.

9. REPRODUCTIVE FREEDOM

Birth control means a woman can complete her education, join the workforce, and plan her own life. Issues like REPRODUCTIVE FREEDOM and a woman’s right to decide when and whether to have children entered public discourse in the 1960s and continue to be debated in public and private forums.

The birth control pill (the pill) contains two hormones (estrogen and a progestin) to stop the ovaries from releasing eggs. The birth control pill (combination oral contraceptives) also thickens the cervical mucus to prevent sperm from reaching the egg. The mini pill is an oral contraceptive with only one hormone (progestin) and may prevent the ovaries from releasing eggs.

In 1957, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first birth control pill (Enovid) for “severe menstrual distress.” In 1960, the pill was approved as a contraceptive; yet the pill was illegal in some states. Its prescription was limited to married women, for purposes of family planning. By 1965, almost 6.5 million American women were taking the pill. The vague nickname is a result of associated stigma as women spoke to their doctors as discreetly as possible. That same year, the Supreme Court struck down state laws prohibiting contraception use, though only for married couples. It was not until 1972 that birth control was approved for all women, regardless of marital status.

FEMINISM IS NOT JUST FOR OTHER WOMEN

QUESTIONS

Is this new information for you?

What reactions and words came to mind as you read through this list? Are your reactions as symbolically potent as what each fact means to you after some consideration?

Are you surprised by any of these facts?

What do you understand when you read, “Feminism is NOT just for other women”? What does FEMINISM mean to you?

Are you a FEMINIST?

With whom can you discuss your responses to this material? How did these conversations work for you?

FEMINISM IS NOT JUST FOR OTHER WOMEN

A FORMER STUDENT RESPONDS

Students were asked to answer these questions and to research the Canadian experience. One learner’s response was intensely researched, interesting to read, and well written. Thank you, Joan (student 2020) for going that extra mile.

Wherever you are –I hope you and yours are healthy and doing well.

Sending all good things,

mark

FEMINISM IS NOT JUST FOR OTHER WOMEN

meet Joan (Student, 2020)

Many of these actions seem crazy for a woman to be unable to do only 50 years ago. I attempted to determine the time frame that these events became available to women in Canada.

CANADIAN TIMELINE

In Canada, it was 1964 when women were first able to open bank accounts without having their husbands present or getting their signatures (PSAC 2019). In the U.S, before 1974, women were often discriminated against when applying for credit and credit cards. They often had to be accompanied by their husbands or interrogated with numerous personal questions. I could not find the exact dates on which women could obtain credit and credit cards in Canada. It is quite crazy to think something as necessary as banking and finance were forbidden to women.

In the United States and Canada, it became illegal in 1978 for employers to fire women due to pregnancy (PSAC 2019). In the U.S., this change happened due to the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, while in Canada, it was the amending of the Canadian Labour Code. Before these changes, women were discriminated against and often dismissed from employment due to their pregnancies.

Women were allowed to serve as jury members starting in 1975 in the U.S. In Manitoba, Canada, the first women are entitled to serve on a jury in 1952 (PSAC 2019). In 1989 in Canada, all military operations that involved direct combat became available for women (Defense, 2020). However, it was not until 2001 when the submarine service became available to women as well. The United States did not allow women to serve in combat roles, including the artillery, armor, and infantry, until 2013. In both countries, women were allowed to help serve the military in non-combat roles long before these dates, for duties such as cooking, nurses, and supporting roles.

In the United States, eight universities make up the Ivy League. These schools provided prestigious education and have extensive resources. Women were not permitted to attend any of the Ivy League schools until 1983. This was only 40 years ago, and this prohibition may contribute to the gender wage gap. In 1862, the Mount Allison University became the first university in Canada to allow female students (PSAC 2019).

Legal action against workplace sexual harassment took extensive and hard work to become official in both countries. The term sexual harassment finally entered legal discourse in 1975. By 1977, women were officially allowed to sue their employers for sexual harassment. However, the first successful legal action happened in 1986. Similarly in Canada, legal action against sexual harassment was first introduced in the 1970s and officially entered Canada’s Labour Code in 1984 (Stoddard, 2014).

Perhaps the most disturbing fact involves spousal rape. In the United States, spousal rape was not criminalized in all states until 1993. The fact that women were allowed to be raped by their spouses in the United States as recently as 27 years ago is both shocking and horrifying. Before 1979 the criminal code assumed permanent, irrevocable consent in marriage. Spousal rape was made illegal in Canada earlier, in 1983 (PSAC 2019). Despite these legal victories associated with spousal rape, significant forms of gender discriminations remain.

In the United States, women were finally able to obtain health insurance at the same monetary rate as men, without sex discrimination in 2010; however, this rule did not come into effect until 2014. Information about Canadian women and the cost of health insurance is significantly different, given Canada’s provisions of the 1984 Canadian Health Act.

Lastly, the right to control reproduction and take contraceptives is still a controversial decision. In both Canada and the U.S., birth control pills were approved for therapeutic usage like the alleviation of menstrual symptoms. It was not until 1972 in the U.S. and 1969 in Canada that birth control was legal for controlling women’s reproduction (CPHA 2020). Many people currently still argue against birth control usage and do not believe women should have this right.

REACTIONS/RESPONSES

Canada and the United States had very similar timelines for allowing women’s rights to these actions. Many of the dates were quite shocking for someone living in today’s culture; it seems as though most sex discrimination was long in the past. However, after reading research, it is apparent many gender-related issues did not get resolved until very recently. Nonetheless, many people still believe women should not have some of these rights, and gender-related legal issues are still not fully resolved.

Each of these rights is one that I would not give a second thought to throughout my day. This is not because these rights are not important, but because I would not think that women would have to fight to have these necessary fundamental rights given to them. It angers me and saddens me thinking about all women had to go through to get the simplest of rights. It angers me to see how women experienced discrimination for no reason other than they lack a penis. Although many of these issues have made great legal strides, they still impact people every day.

One of the most prevalent issues still facing women today is sexual harassment in the workplace. There are still numerous cases of sexual harassment in the workplace that do not get resolved with legal action. In many cases, when women come forward, they are silenced or dismissed, rather than having justice served. Many people are too fearful of coming forward about sexual harassment, fearing the repercussions. In 2016 Canada, around 4% of women reported that they experienced sexual harassment in the workplace (Moyser & Hango, 2018). Of these women, young women and lesbian or bisexual women were often the targets. These cases only include women who reported sexual harassment, excluding unreported incidents.

I believe more cases go unreported because of the feared and real consequences. About 56% of the reported cases have been women targeted by clients or customers (Moyser & Hango, 2018). However, this data leads me to question whether customers target women more often or if women feel more comfortable reporting cases with clients and customers as there are fewer repercussions associated than if they were to report a superior or co-worker. I know many women who have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace and have not reported it, which leads me to believe there is a large percentage of women unaccounted for in these statistics. Studies found that 87% to 94% of individuals that experienced workplace harassment did not formally report it (Feldblum and Lipnik 2016). Therefore, there are no accurate numbers of women facing sexual harassment in the world today.

There are also current issues associated with women’s right to serve in the military. Despite the significance of women’s right to fight in military combat roles (1989 in Canada; 2013 in the United States), women in the military face significantly high cases of sexual assault or sexual harassment by their superiors or their fellow soldiers. From 2006 to 2018, the U.S. military’s percentage of sexual assault reports quadrupled, from 7% (in 2006) to 30% by 2018 (U.S. Department of Defense, 2020). In Canada, reported sexual assault by women in the armed forces is around 4.6% (CBC News, 2019). Despite this seemingly low number, it is crucial to note these numbers represent reported cases of sexual assault, and do not include sexual harassment.

Despite the strides we made since 1971, the work of feminist activism is not over. Every victory comes with setbacks, and despite what many people believe, we still have a long way to go before women reach true equality.

| WE STILL HAVE A LONG WAY TO GO BEFORE WOMEN REACH TRUE EQUALITY. Joan (student, 2020) |

References:

Canadian Public Health Association. “History of Family Planning in Canada.” Canadian Public Health Association | Association Canadienne De Santé Publique, 2020, www.cpha.ca/history-family-planning-canada.

CBC News. “Sexual Misconduct Persists in Military despite Efforts to Curb Assault, StatsCan Reports | CBC News.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 23 May 2019, www.cbc.ca/news/politics/sexual-misconduct-military-operation-honour-1.5144601.

Defence, National. “Women in the Canadian Armed Forces.” Women in the CAF | Canadian Armed Forces, 2020, forces.ca/en/women-in-the-caf/.

Evon, Dan, and Dan Evon. “Could Women Not Do These 9 Things in 1971?” Snopes.com, 3 Sept. 2019, www.snopes.com/fact-check/9-things-women-could-not-do/.

Feldblum, Chai R, and Victoria A Lipnic. “Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace.” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, June 2016, www.eeoc.gov/select-task-force-study-harassment-workplace.

Moyser, Melissa, and Darcy Hango. Harassment in Canadian Workplaces, Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, 17 Dec. 2018, www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2018001/article/54982-eng.htm.

PSAC AFPC. “Canadian Women’s History.” Public Service Alliance of Canada, 6 Mar. 2019, psac-ncr.com/canadian-womens-history.

Stoddart, Jennifer. “Women and the Law.” Edited by Lilian Macpherson, Women, and the Law | The Canadian Encyclopedia, Aug. 2014, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/women-and-the-law.

Urgiles, Margarita Eva. Harassment of women in the military by male military personnel. Diss. Rutgers University-Camden Graduate School, 2015.

U.S. Department of Defense. Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2019 Annual Report on … 2020. <http://www.media.defense.gov/2020/Apr/30/2002291660/-1/-1/1/1_department_of_defense_fiscal_year_2019_annual_report_on_sexual_assault_in_the_military.pdf>.

FEMINISM IS NOT JUST FOR OTHER WOMEN

Summer 2021

A LETTER to my STUDENTS

Conflicting information and binary logics continue to reduce pandemic realities to divided political ideologies. In the context of second wave feminism, I learned the expressions “my body, my choice” and “keep your laws off my bodies” to address the fundamental questions of a women’s rights, women’s sexual desires, family planning, and most contentious, the questions related to legal abortions. When does life begin? For me, this begs other questions like: What is life? What is consciousness? Who decides what is legal? How much can science influence political decision making? I could go on. For each simple answer, I tend to ask hundreds of additional questions. Question-asking helps me delay my reactive triggers and directs my conscious thinking toward symbolic and responsive thought.

Of course, there are always multiple points of view. There are always alternative perceptions to any phenomena. I was recently arguing with another faculty member who uses a lock-down browser (like Respondus or Proctorio) during exams, to maintain academic integrity for accreditation and compliance—in other words, to prevent cheating.

This faculty member didn’t understand my argument against these platforms—the tool was accepted without questions. For her, these platforms were a natural and necessary part of online testing,

Hold on a sec.

New technologies have purposes—to maintain academic integrity; and new technologies have functions or the unintended consequences. That means there are always winners and losers, and new technologies can radically change a culture, in this case the culture of higher education. Change can be both radical and invisible. How do you think lock-down browsers are changing what it means to be educated? What ideological values are amplified, reversed, or made obsolete?

The growth of lock-down browser technology (and industry) since COVID hit last year is something like 900%. Imagine, millions of algorithmically proctored tests are happening around the world. For students like you, these platforms take control of your web browser to mimic exam-like settings. You are prompted to identify yourself, wave your webcam around the room to record the environment, and then, the platform monitors your every movement during the exam. There is no doubt in my mind that algorithmic proctoring is a surveillance technology reinforcing white supremacy, sexism, ableism, transphobia, and other forms of digital oppression. The tools are an invasion of your privacy and, often, your charter rights. New technologies, in general, have a pattern of reinforcing structural oppression like racism and sexism and these same biases are revealed in test proctoring software, disproportionately impacting marginalized students.

For example, if you identify as BIPOC, depending on the colour of your skin, you may be prompted to shine more light on your face or accused of misconduct. If the technology cannot verify your identity, you can be totally locked out of the exam. Imagine: you arrive at the gym for an early morning test and <BAM, CRASH> the doors are locked. You know the room is full of other students—because of your skin colour or gender identity or gender expression you are denied access. (If this interests you, I highly recommend Ruha Benjamin’s 2019 book Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity Press.) Digital proctoring platforms also flag ambient or anyone who leaves the camera’s view as reprehensible. You cannot go to the bathroom! Say you have a medical condition and must use the bathroom, or step away to care for a family member—these actions make you suspect and can impact your academic standing.

In other words, I don’t always think there are multiple points of view. Sometimes, yes/no or fight/flight and other binaries, linguistic dichotomies are necessary. I say no to lock down browsers. I say yes to abortions. I say no to Meryl Streep. I say yes to sugar. I say no to cats. I say . . . my yes/no opinions can soon get on your nerves. IF you disagree, we have entered an ideological conflict. Ultimately, the person with the stronger argument wins. Stronger arguments rely on evidence. And if we really can’t find a middle ground or compromise, there are judicial processes where final outcomes are exact. This other faculty member and I will continue arguing about this issue. We both believe our own stories about what is ethical. HOWEVER, the judicial system is set up to address this adversarial logic, and there are Supreme Courts—where the final answer directs our epistemological worldviews.

Eventually lock-down browsers will be disputed in the courts and debated until the Supreme Court agree to hear the case and both sides of this story. This will happen. And the court’s ruling will be final and further direct the culture of higher education. I am so certain of my convictions—because I’ve been studying media and technologies like these for thirty years and it’s obvious to me how bias is reinforced. We need another system—we need alternative forms of assessment (like the assignments in this class). However, until this issue is addressed in the courts, faculty will continue fighting about ethical education.

What do you think about lock down browsers?

Back to “my body my choice.”

Lately, I’ve heard this language—in COVID times, it is the anti-masking, anti-vaccination groups taking up the logic of feminism. Do you think you have the right to not get vaccinated? Do you think you have the right to tell a woman not to have an abortion?

A Texas law made criminalized any act that assisted a woman in getting an abortion. Roe v. Wade, the legal battle heard by the US Supreme Court (from 1971- 1973), was about a woman’s right to have an abortion without unnecessary government policy or restrictions.

According to Chief Justice Warren Berger, this Texas law violated women’s rights. The U.S. Constitution provides a fundamental right to privacy protecting a pregnant woman’s liberty (to say yes/no to abortions). This right is not absolute. The US government maintains an interest in protecting women’s health and protecting prenatal life. Nonetheless, the decision in Roe v. Wade reshaped politics, dividing people into pro-abortion rights or anti-abortion movements. There are still grassroots movements (on both sides) claiming their point of view is right (and the other wrong). But for this issue—in Canada and the US, women maintain legal control over their bodies and can find support for a safe, legal, medically sponsored abortion. Yup. Keep your laws off my body. [and I’m double vax’d and ready for a booster so we can all go dancing.]

HOWEVER

Summer 2021. As I argue with faculty about the university’s plans to return to campus life because the pandemic is no longer a threat—I also recognize and point out that in other parts of the world, life is much, much worse. Today, as you prepare to go to school, women in Afghanistan are putting on burqas—with full knowledge that they no longer matter (to government, at least) and that their identities are about to be erased.

The Taliban regime fell in 2001 and finally women in Afghanistan were granted what you’d consider basic freedoms, like equal rights (under the law), protection from violence (legally, only after a court ruling in 2009), protection from underage marriages. When, in 2004, the Afghan Constitution granted women equal rights under the law, they could go to school. Against complex social relations and histories, many women did attend school.

Today, the Taliban are in control of Kabul. Women must wear a burka and hijab—covered head-to-toe; women are not allowed in public without a male guardian; women cannot vote; women cannot work; women cannot attend any school after the age of 12. Given the Taliban’s past actions, if women break any of these laws, they risk their lives. They legally may be beaten, whipped, or killed. Today in Kabul, if a woman is accused of adultery she will be stoned to death. If you’re queer, like me, you risk your life. Soon, I expect to hear news of the Taliban tossing gay men from rooftops of tall buildings to a violent death.

The message in my long letter: DO NOT take your rights for granted, my friends. Politics can change. Tides can turn. You must continuously fight for what you believe to be ethical, or risk losing you rights. History has many stories like the Taliban in Kabul today. Speak up or risk the choices of PAPALEGBA. Some say history is the story of the winners. I believe half of that is incorrect. History is the story of the person with the loudest voice. Hello. Can you hear me?

Meanwhile, please get yourself and your loved ones vaccinated, so we can meet on campus continue this discussion over tea. Take care of yourself. Get outside. You are great. As you are.

All good things,

@marklipton

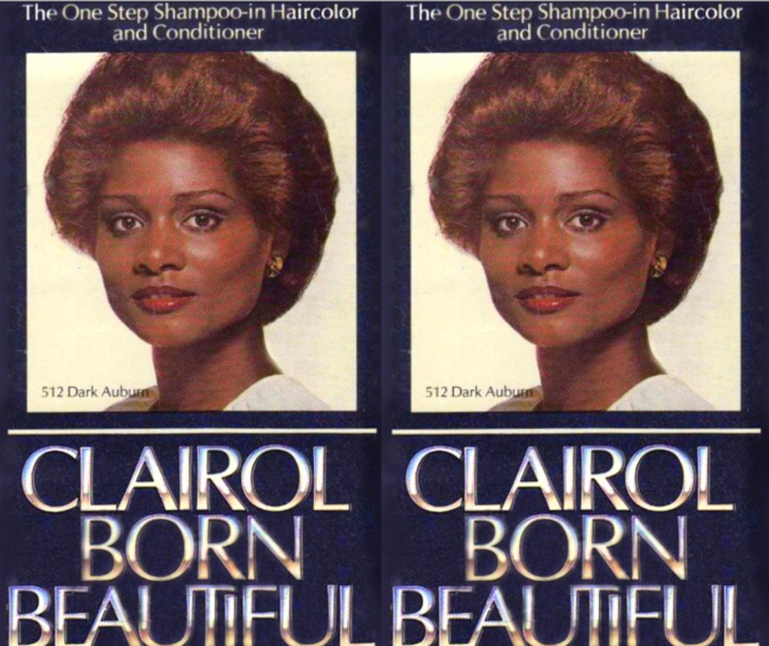

MEET TRACEY AFRICA

Working as a model in the ‘70s and ‘80s, Tracey Norman did not disclose her transgender identity. She was discovered by celebrated fashion photographer Irving Penn, featured on the Clairol box, and Essence magazine. She was outing in an era of intolerance, ending her career. Tracey Norman made history as the first transgender model. I think she deserves greater attention and recognition. And she is my friend.

VIDEO SPOTLIGHT

Clairol’s Nice ‘n Easy presents Real Color Stories: Tracey Norman, the first Black transgender model.

QUESTIONS

What are the HEGEMONIC values of beauty? Where did they come from? How are corporate values of beauty challenged by Tracy Norman?

Do you understand the concept of passing? For all transgender folxs, how might passing be experienced differently? How is the concept of passing implicated in INTERSECTIONAL approaches?

Is it surprising that Tracy Norman passed? How do you feel about Clairol as a company? Did the corporation respond appropriately? Why or why not?

WOMEN OF THE WORLD POETRY SLAM

VIDEO SPOTLIGHT: MEET SARAH JONES & JAXMYN

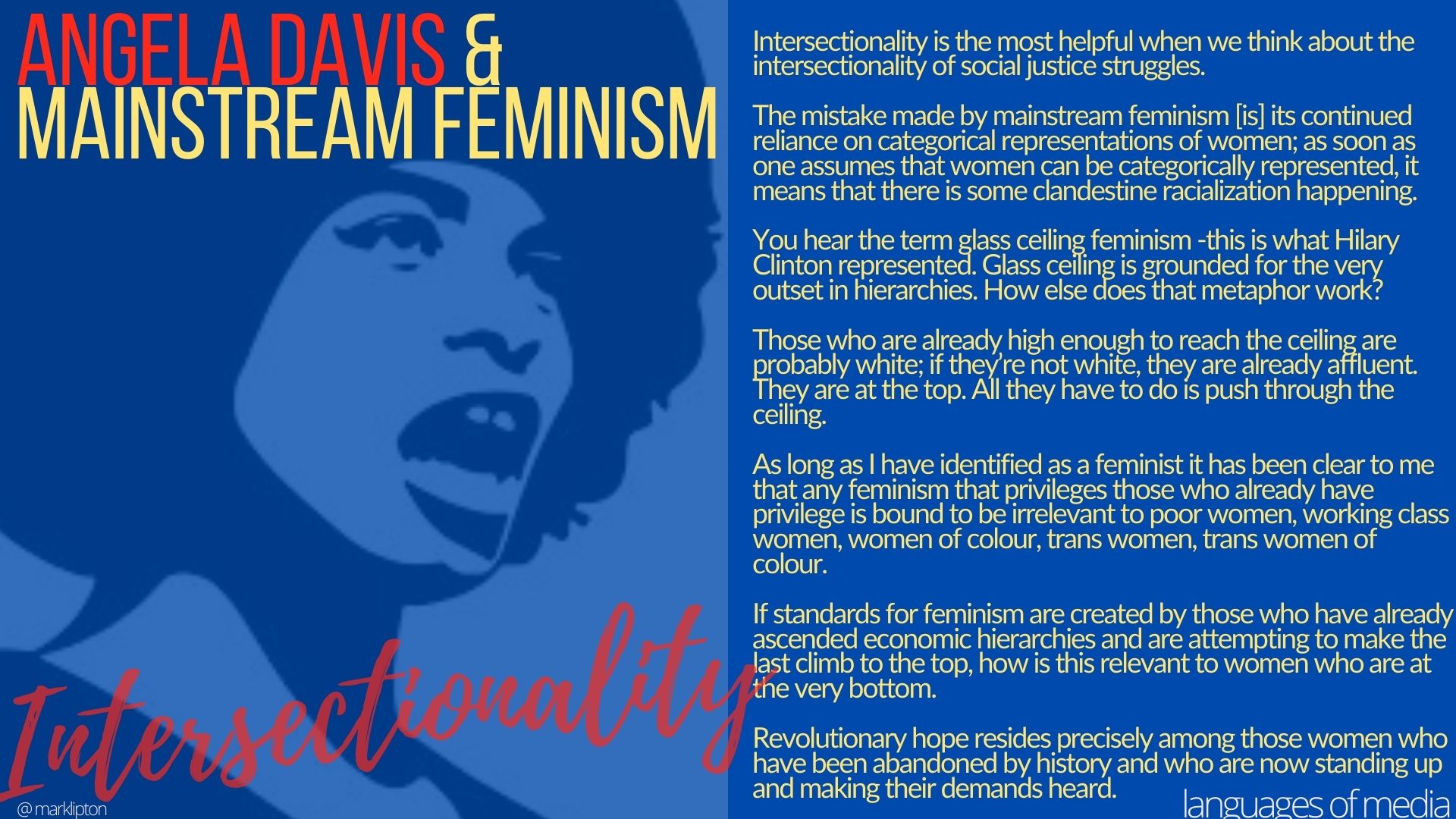

ANGELA DAVIS: REVOLUTION or RESISTANCE?

Angela Davis (Birmingham, 1944) is a politician, activist, and Professor Emerita at the University of California Santa Cruz. A member of the Black Panthers and the Communist Party USA in the sixties, Angela Davis is a feminist and revolutionary of reference. Considered one of the major historical figures in the struggle for human rights and against racial discrimination, in this lecture she discusses the meaning of revolution in our times.

Angela Davis (Birmingham, 1944) is a politician, activist, and Professor Emerita at the University of California Santa Cruz. A member of the Black Panthers and the Communist Party USA in the sixties, Angela Davis is a feminist and revolutionary of reference. Considered one of the major historical figures in the struggle for human rights and against racial discrimination, in this lecture she discusses the meaning of revolution in our times.

|

REVOLUTION TODAY: AN EIGHT-AND-A-HALF-MINUTE SELECTION ON BOURGEOIS FEMINISM TRANSCRIPT And perhaps that we move on to say that… You know, the mainstream feminist movement has made serious, serious mistakes. I often point out that when I wrote a book that was published in 1981 called Women, Race and Class everybody started referring to me as a feminist and my response was, I’m not a feminist. You know, I’m a black revolutionary, because I didn’t see how the two had anything to do with each other. I realized that I was talking about a certain kind of feminism, a bourgeois feminism. A feminism that is still unfortunately… White. Yeah white, white bourgeois feminism, which is unfortunately the most represented feminism today and what most people think of as feminism. But that ignores the fact that huge numbers of organic and academic intellectuals who are women of colour have transformed the very nature of feminism. The hallmark of feminism today is what we call intersectionality. A recognition of… not only the interrelating character of identities but, as I frequently say, I think intersectionality is most helpful when we think about the intersectionality of social justice struggles. The mistake made by mainstream feminism is its continued reliance on categorical representations of women. As soon as one assumes that women can be categorically represented it means that there is some clandestine racialization happening there, right. You hear the term “glass ceiling feminism.” Glass ceiling feminism: This is what Hillary Clinton represented. But glass ceiling feminism is represented, it’s grounded from the very outset in hierarchies. How else does that metaphor work?

Those who are already high enough to reach the ceiling are probably white and then if they are not white, they are already affluent because they’re at the top. All they have to do is push through the ceiling. And as long as I have identified as a feminist it has been clear to me that any feminism that privileges those who already have privilege is bound to be irrelevant to poor women, working-class women, women of color, trans women, trans women of color. If standards for feminism are created by those who have already ascended economic hierarchies and are attempting to make the last climb to the top, how is this relevant to women who are at the very bottom? Revolutionary hope resides precisely among those women who have been abandoned by history and who are now standing up and making their demands heard. I truly believe, and men should applaud this, that this is the era of women. I truly believe that. I am referring not to the women who only have to break the ceiling to get where they want to go. I’m referring to the women at the very bottom: poor women, black women, Muslim women, Indigenous women, queer women, trans women. As a matter of fact, trans women of color have been most despised, most subject to state violence, most subject to individual violence. It seems to me that, we can say that when people who have suffered in that way, when they begin to rise, the whole world will rise with them. The whole world will rise with them. If we stand up against racism, we want much more than inclusion. Inclusion is not enough. Diversity is not enough. And as a matter of fact, we do not wish to be included in a racist society. If we say no to hetero patriarchy, then we do not want to be assimilated into a misogynist and hetero patriarchal society. If we say no to poverty, we do not want to be contained by a capitalist structure that values profits more than human beings.

I want to conclude by suggesting that our notion of revolution, our notions of revolution need to be far more capacious than they have been in the past. Certainly, we need to dispose of what has become an unmanageable system of global capitalism that permits the eight richest billionaires in the world to control as much wealth as the poorest half of the population. That is absolutely obscene. Even those billionaires should think that it’s obscene. Also recognize that we must be prepared to continually challenge that which appears to us to be most normal. Revolution upsets normative processes, class-based, gender based, race-based sexuality based, ability based and I’m just beginning the list. And in this sense, there will always be revolutions looming in the future. Thank you very much. Full presentation: <https://www.cccb.org/en/multimedia/videos/angela-davis/227656>. |

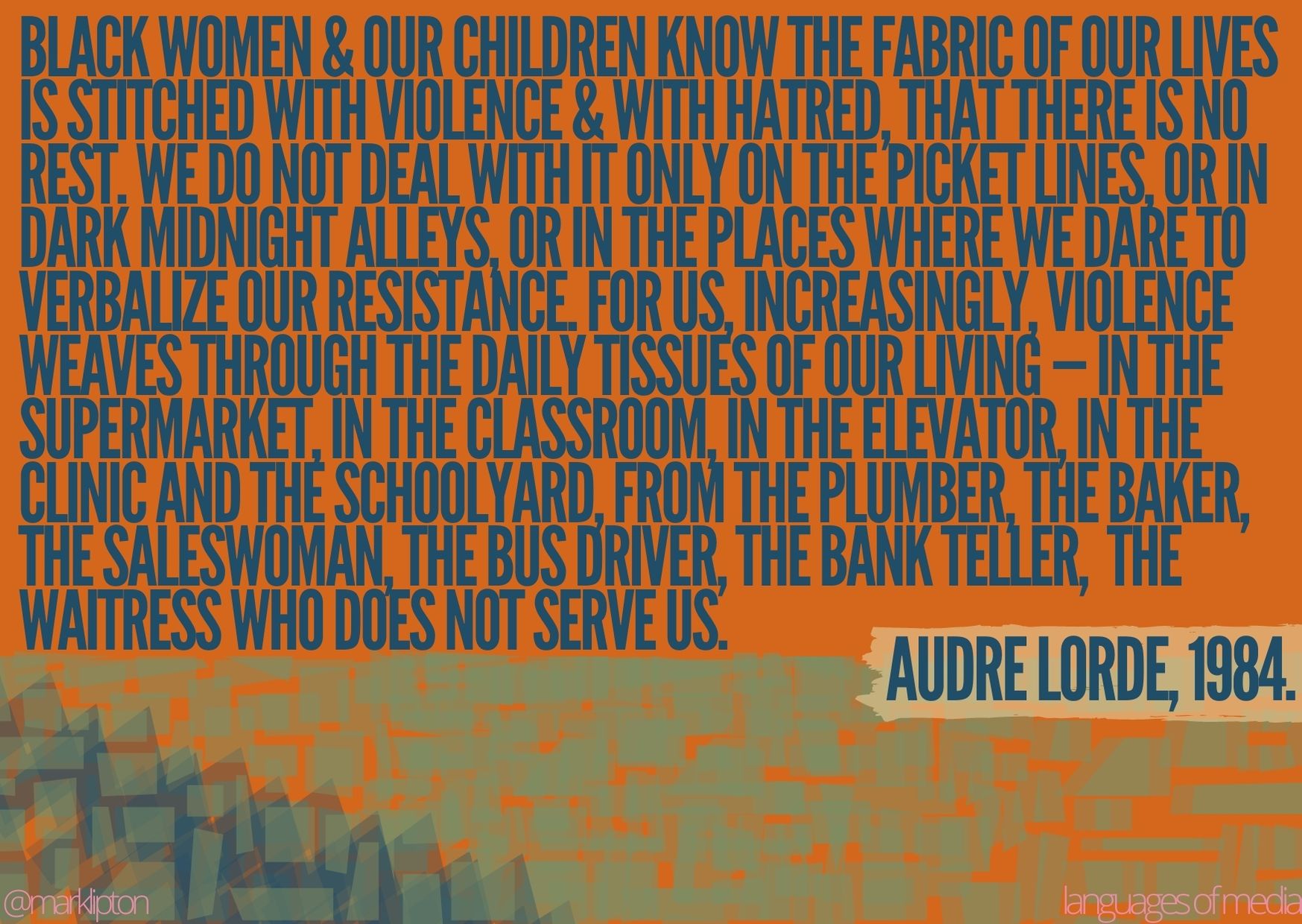

MEET AUDRE LORDE

Audre Lorde was a self-described “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” who dedicated her life and her work to confronting and addressing injustices of racism, sexism, classism, capitalism, heterosexism, and homophobia. I met her shortly before her death in 1992 at an ACTUP meeting on 13th Street in New York City’s Greenwich Village. I remember her distinct voice. It was a humid day near the end of summer. Many of the usual gay boys were away and I found myself in a different kind of ACTUP meeting.

The familiar room felt especially crowded at the Gay and Lesbian Centre. I recall trying to hide in a corner behind a book, as I usually did at the time. On this day, I felt odd, I stood out despite the packed auditorium. The meeting had not yet begun. The heat made everything feel sticky. Even the voices I was overhearing felt like tacky, sticking to me like chewed gum. I didn’t know anyone in the room, but when this person spoke, I felt invited to lean forward—to pay attention. I sought this person out and introduced myself, asking about this or that. It was only afterward, in the men’s bathroom (covered with graffiti by Keith Haring) that a group of older Black women stopped me.

“What was you talking to Audre about?”

“Who?” I asked. The cackling that sprung forth surprised. And I soon recognized delight. Their delight with my not knowing.

“Hack, this young boy don’t even know he was talking with Audre Lorde.”

“Well I never…” More laughing echoed as I open the door to walk past them, into the heat of the street.

REAd

MEET LEIOMY MALDONADO

Vogue Legend Leiomy Maldonado & Nike

Media Attributions

- 01

- 02

- 05

- image18