10.3 Step 1: Conducting a Situational Analysis

Step 1: Conducting a Situation Analysis

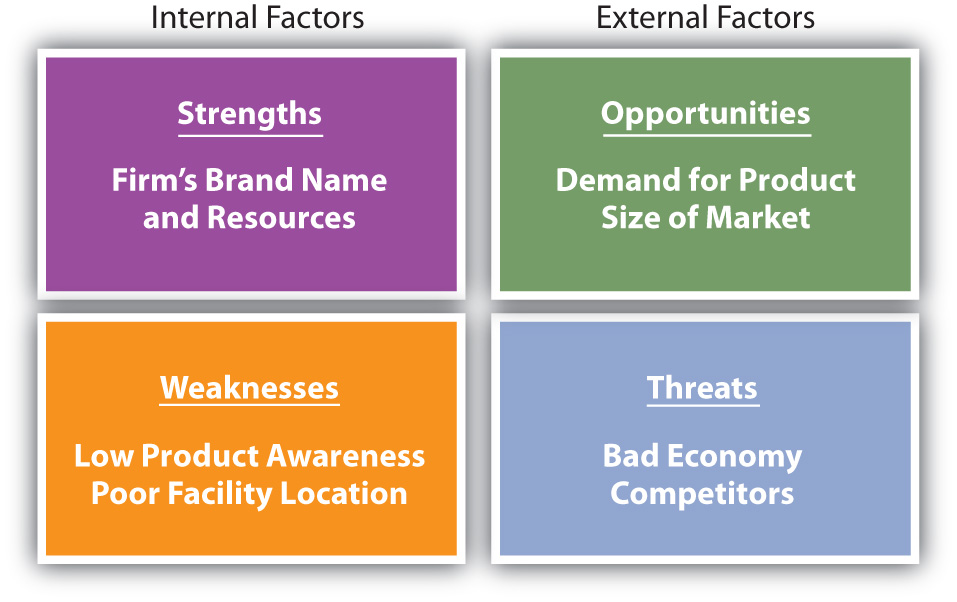

As part of the strategic planning process, a situation analysis must be conducted before a company can decide on specific actions. A situation analysis involves analyzing the external (macro and micro factors outside the organization), the internal (company) environments, and understanding consumer behaviour in order to deliver proper value. Figure 10.8: “Elements of a SWOT Analysis” shows examples of internal and external factors within a SWOT analysis. The firm’s internal environment—such as its financial resources, technological resources, and the capabilities of its personnel and their performance—has to be examined. It is also critical to examine the external macro and micro-environments the firm faces, such as the economy and its competitors. The external environment significantly affects the decisions a firm makes and thus must be continuously evaluated. For example, during the economic downturn in 2008–2009, businesses found that many competitors cut the prices of their products drastically. Other companies reduced package sizes or the amount of product in packages. Firms also offered customers incentives (free shipping, free gift cards with purchase, rebates, etc.) to purchase their goods and services online, which allowed businesses to cut back on the personnel needed to staff their brick-and-mortar stores. While a business cannot control things such as the economy, changes in demographic trends, or what competitors do, it must decide what actions to take to remain competitive—actions that depend in part on their internal environment.

Assessing the Internal Environment

As we have indicated, when an organization evaluates which factors are its strengths and weaknesses, it is assessing its internal environment. Once companies determine their strengths, they can use those strengths to capitalize on opportunities and develop their competitive advantage. For example, strengths for PepsiCo are what are called “mega” brands, or brands that individually generate over $1 billion in sales1. These brands are also designed to contribute to PepsiCo’s environmental and social responsibilities.

PepsiCo’s brand awareness, profitability, and strong presence in global markets are also strengths. Especially in foreign markets, the loyalty of a firm’s employees can be a major strength, which can provide it with a competitive advantage. Loyal and knowledgeable employees are easier to train and tend to develop better relationships with customers. This helps organizations pursue more opportunities.

Although the brand awareness for PepsiCo’s products is strong, smaller companies often struggle with weaknesses such as low brand awareness, low financial reserves, and poor locations. When organizations assess their internal environments, they must look at factors such as performance and costs as well as brand awareness and location. Managers need to examine both the past and current strategies of their firms and determine what strategies succeeded and which ones failed. This helps a company plan its future actions and improves the odds that it will be successful. For example, a company might look at packaging that worked very well for a product and use the same type of packaging for new products. Firms may also look at customers’ reactions to changes in products, including packaging, to see what works and doesn’t work. When PepsiCo changed the packaging of major brands in 2008, customers had mixed responses. Tropicana switched from the familiar orange with the straw in it to a new package and customers did not like it. As a result, Tropicana changed back to their familiar orange with a straw after spending $35 million for the new package design.

Assessing the External Environment

Analyzing the external environment involves tracking conditions in the macro and micro marketplace that, although largely uncontrollable, affect the way an organization does business. The macro-environment includes the factors we discussed in Chapter 2 including economic factors, demographic trends, cultural and social trends, political and legal regulations, technological changes, and the price and availability of natural resources. The microenvironment includes competition, suppliers, marketing intermediaries (retailers, wholesalers), the public, the company, and customers. We focused on the microenvironment in Chapter 3.

When firms globalize, analyzing the environment becomes more complex because they must examine the external environment in each country in which they do business. Regulations, competitors, technological development, and the economy may be different in each country and will affect how firms do business.

Selling an Experience: Marketing Intangible Objects

Understanding Consumer Behaviour

You’ve been a consumer with purchasing power for much longer than you probably realize—since the first time you were asked which cereal or toy you wanted. Over the years, you’ve developed rules of thumb or mental shortcuts providing a systematic way to choose among alternatives, even if you aren’t aware of it. Other consumers follow a similar process, but different people, no matter how similar they are, make different purchasing decisions. You might be very interested in purchasing a Smart Car, but your best friend might want to buy a Ford F-150 truck. What factors influenced your decision and what factors influenced your friend’s decision?

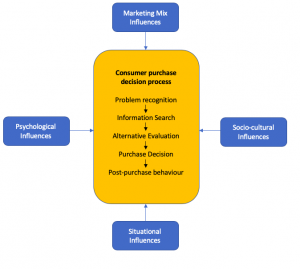

As we mentioned earlier in the chapter, consumer behaviour is influenced by many things, including environmental and marketing factors, the situation, personal and psychological factors, family, and culture. Businesses try to figure out trends so they can reach the people most likely to buy their products in the most cost-effective way possible. Businesses often try to influence a consumer’s behaviour with things they can control such as the layout of a store, music, grouping and availability of products, pricing, and advertising. While some influences may be temporary and others are long-lasting, different factors can affect how buyers behave—whether they influence you to make a purchase, buy additional products, or buy nothing at all. Let’s now look at some of the influences on consumer behaviour in more detail.

The Five-Step Purchase Decision Process

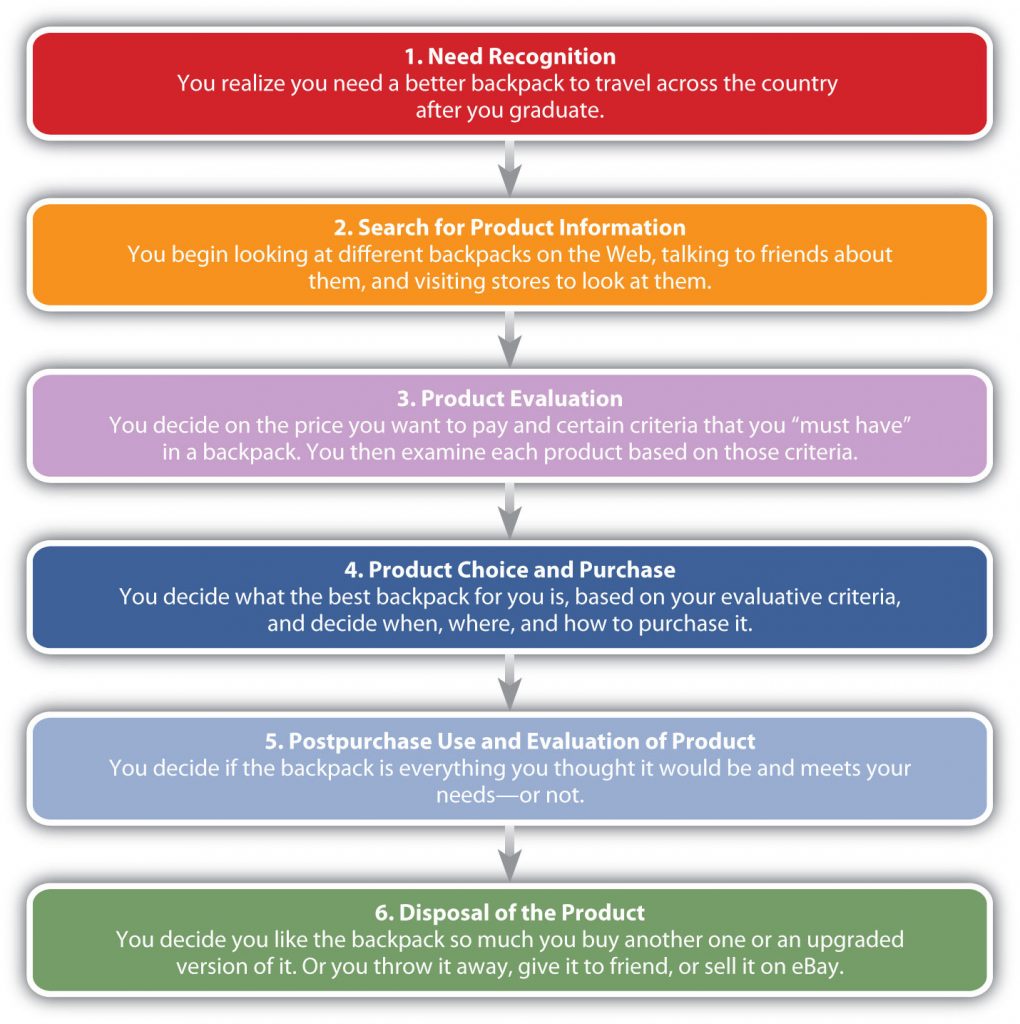

Figure 10.3 outlines the buying stages consumers go through. At any given time, you’re probably in the buying stage for a product or service. You’re thinking about the different types of things you want or need to eventually buy, how you are going to find the best ones at the best price, and where and how will you buy them. Meanwhile, there are other products you have already purchased that you’re evaluating. Some might be better than others. Will you discard them, and if so, how? Then what will you buy? Where does that process start?

Stage 1. Problem Recognition

You plan to backpack around the country after you graduate and don’t have a particularly good backpack. You realize that you must get a new backpack. You may also be thinking about the job you’ve accepted after graduation and know that you must get a vehicle to commute. Recognizing a need may involve something as simple as running out of bread or milk or realizing that you must get a new backpack or a car after you graduate. Marketers try to show consumers how their products and services add value and help satisfy needs and wants. Do you think it’s a coincidence that Gatorade, Powerade, and other beverage makers locate their machines in gymnasiums so you see them after a long, tiring workout? Previews at movie theatres are another example. How many times have you have heard about a movie and had no interest in it—until you saw the preview? Afterward, you felt like you had to see it.

Stage 2. Information Search

For products such as milk and bread, you may simply recognize the need, go to the store, and buy more. However, if you are purchasing a car for the first time or need a particular type of backpack, you may need to get information on different alternatives. Maybe you have owned several backpacks and know what you like and don’t like about them. Or there might be a particular brand that you’ve purchased in the past that you liked and want to purchase in the future. This is a great position for the company that owns the brand to be in—something firms strive for. Why? Because it often means you will limit your search and simply buy their brand again.

If what you already know about backpacks doesn’t provide you with enough information, you’ll probably continue to gather information from various sources. Frequently people ask friends, family, and neighbours about their experiences with products. Perhaps you’ll look to see if your favourite influencer has done a product review. Magazines such as Consumer Reports (considered an objective source of information on many consumer products) or Backpacker Magazine might also help you. Similar information sources are available for learning about different makes and models of cars.

Internet shopping sites such as Amazon.com have become a common source of information about products. Epinions.com is an example of a consumer-generated review site. The site offers product ratings, buying tips, and price information. Amazon.com also offers product reviews written by consumers. People prefer “independent” sources such as this when they are looking for product information. However, they also often consult non-neutral sources of information, such as advertisements, brochures, company Web sites, and salespeople.

Stage 3. Alternative Evaluation

Obviously, there are hundreds of different backpacks and cars available. It’s not possible for you to examine all of them. In fact, good salespeople and marketing professionals know that providing you with too many choices can be so overwhelming that you might not buy anything at all. Consequently, you may use choice heuristics or rules of thumb that provide mental shortcuts in the decision-making process. You may also develop evaluative criteria to help you narrow down your choices. Backpacks or cars that meet your initial criteria before the consideration will determine the set of brands you’ll consider for purchase.

Evaluative criteria are certain characteristics that are important to you such as the price of the backpack, the size, the number of compartments, and the colour. Some of these characteristics are more important than others. For example, the size of the backpack and the price might be more important to you than the colour—unless, say, the colour is hot pink and you hate pink. You must decide what criteria are most important and how well different alternatives meet the criteria.

Companies want to convince you that the evaluative criteria you are considering reflect the strengths of their products. For example, you might not have thought about the weight or durability of the backpack you want to buy. However, a backpack manufacturer such as Osprey might remind you through magazine ads, packaging information, and its Web site that you should pay attention to these features—features that happen to be key selling points of its backpacks. Automobile manufacturers may have similar models, so don’t be afraid to add criteria to help you evaluate cars in your consideration set.

Stage 4. Purchase Decision

With low-involvement purchases, consumers may go from recognizing a need to purchasing the product. However, for backpacks and cars, you decide which one to purchase after you have evaluated different alternatives. In addition to which backpack or which car, you are probably also making other decisions at this stage, including where and how to purchase the backpack (or car) and on what terms. Maybe the backpack was cheaper at one store than another, but the salesperson there was rude. Or maybe you decide to order online because you’re too busy to go to the mall. Other decisions related to the purchase, particularly those related to big-ticket items, are made at this point. For example, if you’re buying a high-definition television, you might look for a store that will offer you credit or a warranty.

Stage 5. Post-purchase Behaviour

At this point in the process, you decide whether the backpack you purchased is everything it was cracked up to be. Hopefully it is. If it’s not, you’re likely to suffer what’s called post-purchase dissonance. You might call it buyer’s remorse. Typically, dissonance occurs when a product or service does not meet your expectations. Consumers are more likely to experience dissonance with products that are relatively expensive and that are purchased infrequently.

You want to feel good about your purchase, but you don’t. You begin to wonder whether you should have waited to get a better price, purchased something else, or gathered more information first. Consumers commonly feel this way, which is a problem for sellers. If you don’t feel good about what you’ve purchased from them, you might return the item and never purchase anything from them again. Or, worse yet, you might tell everyone you know how bad the product was.

Companies do various things to try to prevent buyer’s remorse. For smaller items, they might offer a money-back guarantee or they might encourage their salespeople to tell you what a great purchase you made. How many times have you heard a salesperson say, “That outfit looks so great on you!” For larger items, companies might offer a warranty, along with instruction booklets, and a toll-free troubleshooting line to call or they might have a salesperson call you to see if you need help with the product. Automobile companies may offer loaner cars when you bring your car in for service.

Companies may also try to set expectations in order to satisfy customers. Service companies such as restaurants do this frequently. Think about when the hostess tells you that your table will be ready in 30 minutes. If they seat you in 15 minutes, you are much happier than if they told you that your table would be ready in 15 minutes, but it took 30 minutes to seat you. Similarly, if a store tells you that your pants will be altered in a week and they are ready in three days, you’ll be much more satisfied than if they said your pants would be ready in three days, yet it took a week before they were ready.

Factors Influencing the Purchase Decision Process

Throughout the entire process, consumers face several external factors that influence their purchase decision. Figure 10.5 illustrates the different influences that attribute to a consumer’s final decision.

Situational Factors

Have you ever been in a department store and couldn’t find your way out? No, you aren’t necessarily directionally challenged. Marketing professionals take physical factors such as a store’s design and layout into account when they are designing their facilities. Presumably, the longer you wander around a facility, the more you will spend. Grocery stores frequently place bread and milk products on the opposite ends of the stores because people often need both types of products. To buy both, they have to walk around an entire store, which of course, is loaded with other items they might see and purchase.

Store locations also influence behaviour. Starbucks has done a good job in terms of locating its stores. It has the process down to a science; you can scarcely drive a few miles down the road without passing a Starbucks. You can also buy cups of Starbucks coffee at many grocery stores and in airports—virtually any place where there is foot traffic.

Physical factors that firms can control, such as the layout of a store, music played at stores, the lighting, temperature, and even the smells you experience are called atmospherics. Perhaps you’ve visited the office of an apartment complex and noticed how great it looked and even smelled. It’s no coincidence. The managers of the complex were trying to get you to stay for a while and have a look at their facilities. Research shows that “strategic fragrancing” results in customers staying in stores longer, buying more, and leaving with better impressions of the quality of stores’ services and products. Mirrors near hotel elevators are another example. Hotel operators have found that when people are busy looking at themselves in the mirrors, they don’t feel like they are waiting as long for their elevators (Moore, 2008).

Not all physical factors are under a company’s control, however. Take weather, for example. Rainy weather can be a boon to some companies, like umbrella makers such as Totes, but a problem for others. Beach resorts, outdoor concert venues, and golf courses suffer when it is raining heavily. Businesses such as automobile dealers also have fewer customers. Who wants to shop for a car in the rain?

Firms often attempt to deal with adverse physical factors such as bad weather by offering specials during unattractive times. For example, many resorts offer consumers discounts to travel to beach locations during hurricane season. Having an online presence is another way to cope with weather-related problems. What could be more comfortable than shopping at home? If it’s raining too hard to drive to Lululemon, Aritzia, or Boathouse, you can buy products from these companies and many others online. You can shop online for cars, too, and many restaurants take orders online and deliver.

Crowding is another situational factor. Have you ever left a store and not purchased anything because it was just too crowded? Some studies have shown that consumers feel better about retailers who attempt to prevent overcrowding in their stores. However, other studies have shown that to a certain extent, crowding can have a positive impact on a person’s buying experience. The phenomenon is often referred to as “herd behaviour” (Gaumer & Leif, 2005).

If people are lined up to buy something, you want to know why. Should you get in line to buy it too? Herd behaviour helped drive up the price of houses in the mid-2000s before the prices for them rapidly fell. Unfortunately, herd behaviour has also led to the deaths of people. In 2008, a store employee was trampled to death by an early morning crowd rushing into a Walmart to snap up holiday bargains.

Social Situation

The social situation you’re in can significantly affect your purchase behaviour. Perhaps you have seen Girl Scouts selling cookies outside grocery stores and other retail establishments and purchased nothing from them, but what if your neighbour’s daughter is selling the cookies? Are you going to turn her down or be a friendly neighbour and buy a box (or two)?

Time

The time of day, time of year, and how much time consumers feel like they have to shop affects what they buy. Researchers have even discovered whether someone is a “morning person” or “evening person” affects shopping patterns. Have you ever gone to the grocery store when you are hungry or after payday when you have cash in your pocket? When you are hungry or have cash, you may purchase more than you would at other times. Seven-Eleven Japan is a company that’s extremely in tune with time and how it affects buyers. The company’s point-of-sale systems at its checkout counters monitor what is selling well and when, and stores are restocked with those items immediately—sometimes via motorcycle deliveries that zip in and out of traffic along Japan’s crowded streets. The goal is to get the products on the shelves when and where consumers want them. Seven-Eleven Japan also knows that, like Americans, its customers are “time-starved.” Shoppers can pay their utility bills, local taxes, and insurance or pension premiums at Seven-Eleven Japan stores, and even make photocopies (Bird, 2002).

Companies worldwide are aware of people’s lack of time and are finding ways to accommodate them. Some doctors’ offices offer drive-through shots for patients who are in a hurry and for elderly patients who find it difficult to get out of their cars. Tickets.com allows companies to sell tickets by sending them to customers’ mobile phones when they call in. The phones’ displays are then read by barcode scanners when the ticket purchasers arrive at the events they’re attending. Likewise, if you need customer service from Amazon.com, there’s no need to wait on the telephone. If you have an account with Amazon, you just click a button on the company’s Web site and an Amazon representative calls you immediately.

Reason for the Purchase

The reason you are shopping also affects the amount of time you will spend shopping. Are you making an emergency purchase? What if you need something for an important dinner or a project and only have an hour to get everything? Are you shopping for a gift or for a special occasion? Are you buying something to complete a task/project and need it quickly? In recent years, emergency clinics have sprung up in strip malls all over the country. Convenience is one reason. The other is sheer necessity. If you cut yourself and you are bleeding badly, you’re probably not going to shop around much to find the best clinic. You will go to the one that’s closest to you. The same thing may happen if you need something immediately.

Purchasing a gift might not be an emergency situation, but you might not want to spend much time shopping for it either. Gift certificates have been popular for years. You can purchase gift cards for numerous merchants at your local grocery store or online. By contrast, suppose you need to buy an engagement ring. Sure, you could buy one online in a jiffy, but you probably wouldn’t do that. What if the diamond was fake? What if your significant other turned you down and you had to return the ring? How hard would it be to get back online and return the ring? (Hornik & Miniero, 2009)

Mood

Have you ever felt like going on a shopping spree? At other times wild horses couldn’t drag you to a mall. People’s moods temporarily affect their spending patterns. Some people enjoy shopping. It’s entertaining for them. At the extreme are compulsive spenders who get a temporary “high” from spending.

A sour mood can spoil a consumer’s desire to shop. The crash of the U.S. stock market in 2008 left many people feeling poorer, leading to a dramatic downturn in consumer spending. Penny pinching came into vogue, and conspicuous spending was out. Costco and Walmart experienced heightened sales of their low-cost Kirkland Signature and Great Value brands as consumers scrimped1. Saks Fifth Avenue wasn’t so lucky. Its annual release of spring fashions usually leads to a feeding frenzy among shoppers, but spring 2009 was different. “We’ve definitely seen a drop-off of this idea of shopping for entertainment,” says Kimberly Grabel, Saks Fifth Avenue’s senior vice president of marketing (Rosenbloom, 2009). To get buyers in the shopping mood, companies resorted to different measures. The upscale retailer Neiman Marcus began introducing more mid-priced brands. By studying customer loyalty cards, the French hypermarket Carrefour hoped to find ways to get its customers to purchase nonfood items that have higher profit margins.

The glum mood wasn’t bad for all businesses though. Discounters like Half-Priced books saw their sales surge. So did seed sellers as people began planting their own gardens. Finally, what about those products (Aqua Globes, Snuggies, and Ped Eggs) you see being hawked on television? Their sales were the best ever. Apparently, consumers too broke to go on vacation or shop at Saks were instead watching television and treating themselves to the products (Ward, 2009).

Psychological Factors

Motivation

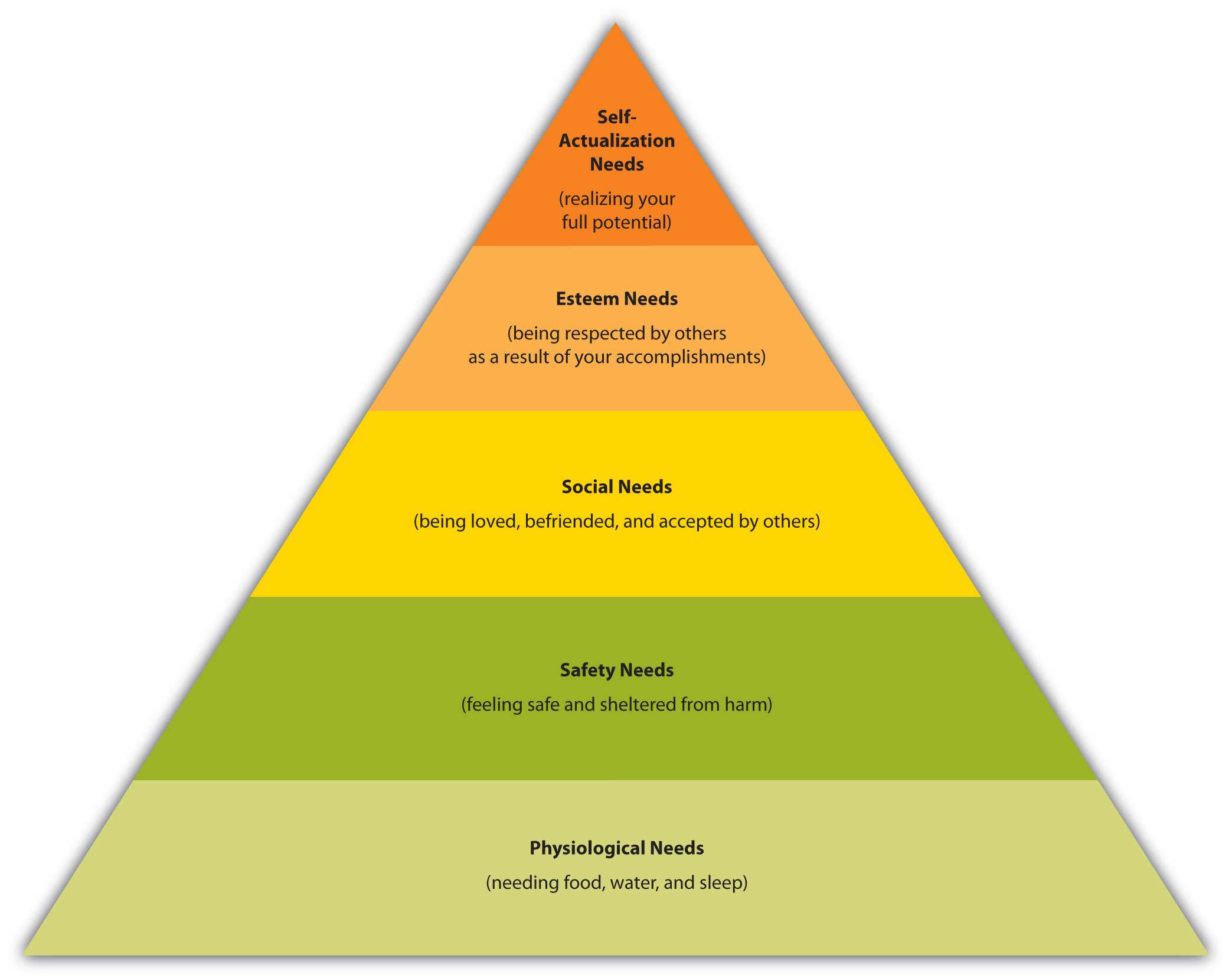

Motivation is the inward drive we have to get what we need. In the mid-1900s, Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist, developed the hierarchy of needs shown in Figure 10.6.

Maslow theorized that people have to fulfill their basic needs—food, water, and sleep—before they can begin fulfilling higher-level needs. Have you ever gone shopping when you were tired or hungry? Even if you were shopping for something that would make you the envy of your friends (maybe a new car) you probably wanted to sleep or eat even more. Forget the car. Just give me a nap and a candy bar.

The need for food is recurring. Other needs, such as shelter, clothing, and safety, tend to be enduring. Still, other needs arise at different points in time in a person’s life. For example, during grade school and high school, your social needs probably rose to the forefront. You wanted to have friends and get a date. Perhaps this prompted you to buy certain types of clothing or electronic devices. After high school, you began thinking about how people would view you in your “station” in life, so you decided to pay for college and get a professional degree, thereby fulfilling your need for esteem. If you’re lucky, at some point you will realize Maslow’s state of self-actualization. You will believe you have become the person in life that you feel you were meant to be.

Following the economic crisis that began in 2008, the sales of new automobiles dropped sharply virtually everywhere around the world—except the sales of Hyundai vehicles. Hyundai understood that people needed to feel secure and safe and ran an ad campaign that assured car buyers they could return their vehicles if they couldn’t make the payments on them without damaging their credit. Seeing Hyundai’s success, other carmakers began offering similar programs. Likewise, banks began offering “worry-free” mortgages to ease the minds of would-be homebuyers. For a fee of about $500, First Mortgage Corp., a Texas-based bank, offered to make a homeowner’s mortgage payment for six months if he or she got laid off (Jares, 2010).

While achieving self-actualization may be a goal for many individuals in the United States, consumers in Eastern cultures may focus more on belongingness and group needs. Marketers look at cultural differences in addition to individual needs. The importance of groups affects advertising (using groups versus individuals) and product decisions.

Perception

Perception is how you interpret the world around you and make sense of it in your brain. You do so via stimuli that affect your different senses—sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. How you combine these senses also makes a difference. For example, in one study, consumers were blindfolded and asked to drink a new brand of clear beer. Most of them said the product tasted like regular beer. However, when the blindfolds came off and they drank the beer, many of them described it as “watery” tasting (Ries, 2009).

Consumers are bombarded with messages on television, radio, magazines, the Internet, and even bathroom walls. In 1999, the average consumer was exposed to about three thousand advertisements per day (Lasn). This number has certainly increased since the study was conducted. Consumers are surfing the Internet, watching television, and checking their cell phones for text messages simultaneously. Some, but not all, information makes it into our brains. Selecting information we see or hear (e.g., television shows or magazines) is called selective exposure.

Have you ever read or thought about something and then started noticing ads and information about it popping up everywhere? Many people are more perceptive to advertisements for products they need. Selective attention is the process of filtering out information based on how relevant it is to you. It’s been described as a “suit of armour” that helps you filter out information you don’t need. At other times, people forget information, even if it’s quite relevant to them, which is called selective retention. Often the information contradicts the person’s belief. A longtime chain smoker who forgets much of the information communicated during an antismoking commercial is an example. To be sure their advertising messages get through to you and you remember them, companies use repetition. How tired of iPhone commercials were you before they tapered off? How often do you see the same commercial aired during a single television show?

Another potential problem that advertisers (or your friends) may experience is a selective distortion or misinterpretation of the intended message. Promotions for weight loss products show models that look slim and trim after using their products, and consumers may believe they will look like the model if they use the product. They misinterpret other factors such as how the model looked before or how long it will take to achieve the results. Similarly, have you ever told someone a story about a friend and that person told another person who told someone else? By the time the story gets back to you, it is completely different. The same thing can happen with many types of messages.

Using surprising stimuli or shock advertising is also a technique that works. One study found that shocking content increased attention, benefited memory, and positively influenced behaviour among a group of university students (Dahl, et. al., 2003).

Subliminal advertising is the opposite of shock advertising and involves exposing consumers to marketing stimuli such as photos, ads, and messages by stealthily embedding them in movies, ads, and other media. Although there is no evidence that subliminal advertising works, years ago the words Drink Coca-Cola were flashed for a millisecond on a movie screen. Consumers were thought to perceive the information subconsciously and to be influenced to buy the products shown. Many people considered the practice to be subversive, and in 1974, the Federal Communications Commission condemned it. Much of the original research on subliminal advertising, conducted by a researcher trying to drum up business for his market research firm, was fabricated (Crossen, 2007). People are still fascinated by subliminal advertising, however. To create “buzz” about the television show The Mole in 2008, ABC began hyping it by airing short commercials composed of just a few frames. If you blinked, you missed it. Some television stations actually called ABC to figure out what was going on. One-second ads were later rolled out to movie theatres (Adalian, 2008).

Different consumers perceive information differently. A couple of frames about The Mole might make you want to see the television show. However, your friend might see the ad, find it stupid, and never tune in to watch the show. One man sees Pledge, an outstanding furniture polish, while another sees a can of spray no different from any other furniture polish. One woman sees a luxurious Gucci purse, and the other sees an overpriced bag to hold keys and makeup (Chartrand, 2009).

Learning

Learning refers to the process by which consumers change their behaviour after they gain information or experience. It’s the reason you don’t buy a bad product twice. Learning doesn’t just affect what you buy; it affects how you shop. People with limited experience with a product or brand generally seek out more information than people who have used a product before.

Companies try to get consumers to learn about their products in different ways. Car dealerships offer test drives. Pharmaceutical reps leave samples and brochures at doctor’s offices. Other companies give consumers free samples. To promote its new line of coffees, McDonald’s offered customers free samples to try. Have you ever eaten the food samples in a grocery store? While sampling is an expensive strategy, it gets consumers to try the product and many customers buy it, especially right after trying in the store.

Another kind of learning is operant or instrumental conditioning, which is what occurs when researchers are able to get a mouse to run through a maze for a piece of cheese or a dog to salivate just by ringing a bell. In other words, learning occurs through repetitive behaviour that has positive or negative consequences. Companies engage in operant conditioning by rewarding consumers, which causes consumers to want to repeat their purchasing behaviours. Prizes and toys that come in Cracker Jacks and McDonald’s Happy Meals, free tans offered with gym memberships, a free sandwich after a certain number of purchases, and free car washes when you fill up your car with a tank of gas are examples.

Another learning process called classical conditioning occurs by associating a conditioned stimulus (CS) with an unconditioned stimulus (US) to get a particular response. The more frequently the CS is linked with the US, the faster learning occurs and this is what advertisers and businesses try to do. Think about a meal at a restaurant where the food was really good and you went with someone special. You like the person and want to go out again. It could be that classical conditioning occurred. That is, the food produced a good feeling and you may associate the person with the food, thus producing a good feeling about the person.

Attitude

Attitudes are “mental positions” or emotional feelings, favourable or unfavourable evaluations, and action tendencies people have about products, services, companies, ideas, issues, or institutions3. Attitudes tend to be enduring, and because they are based on people’s values and beliefs, they are hard to change. Companies want people to have positive feelings about their offerings. A few years ago, KFC began running ads to the effect that fried chicken was healthy—until the U.S. Federal Trade Commission told the company to stop. Wendy’s slogan that its products are “way better than fast food” is another example. Fast food has a negative connotation, so Wendy’s is trying to get consumers to think about its offerings as being better.

An example of a shift in consumers’ attitudes occurred when the taxpayer-paid government bailouts of big banks that began in 2008 provoked the wrath of Americans, creating an opportunity for small banks not involved in the credit bailout and subprime mortgage mess. The Worthington National Bank, a small bank in Fort Worth, Texas, ran billboards reading: “Did Your Bank Take a Bailout? We didn’t.” Another read: “Just Say NO to Bailout Banks. Bank Responsibly!” The Worthington Bank received tens of millions in new deposits soon after running these campaigns (Mantone, 2009).

Lifestyle

If you have ever watched the television show Wife Swap, you can see that despite people’s similarities (e.g., being middle-class Americans who are married with children), their lifestyles can differ radically. To better understand and connect with consumers, companies interview or ask people to complete questionnaires about their lifestyles or their activities, interests, and opinions (often referred to as AIO statements). Consumers are not only asked about products they like, where they live, and what their gender is but also about what they do—that is, how they spend their time and what their priorities, values, opinions, and general outlooks on the world are. Where do they go other than work? Who do they like to talk to? What do they talk about? Researchers hired by Procter & Gamble have gone so far as to follow women around for weeks as they shop, run errands, and socialize with one another (Berner, 2006). Other companies have paid people to keep a daily journal of their activities and routines.

A number of research organizations examine lifestyle and psychographic characteristics of consumers. Psychographics combines the lifestyle traits of consumers and their personality styles with an analysis of their attitudes, activities, and values to determine groups of consumers with similar characteristics. One of the most widely used systems to classify people based on psychographics is the VALS (Values, Attitudes, and Lifestyles) framework. Using VALS to combine psychographics with demographic information such as marital status, education level, and income provides a better understanding of consumers.

Socio-cultural Influences

Situational factors, personal factors, and psychological factors influence what you buy, but only on a temporary basis. Societal factors are a bit different. They are more outward and have broad influences on your beliefs and the way you do things. They depend on the world around you and how it works.

Personality and Self-Concept

Personality describes a person’s disposition, helps show why people are different, and encompasses a person’s unique traits. The “Big Five” personality traits that psychologists discuss frequently include openness (how open you are to new experiences), conscientiousness (how diligent you are), extraversion (how outgoing or shy you are), agreeableness (how easy you are to get along with), and neuroticism (how prone you are to negative mental states.

Do personality traits predict people’s purchasing behaviour? Can companies successfully target certain products to people based on their personalities? How do you find out what personalities consumers have? Are extraverts wild spenders and introverts penny pinchers?

The link between people’s personalities and their buying behaviour is somewhat unclear. Some research studies have shown that “sensation seekers,” or people who exhibit extremely high levels of openness, are more likely to respond well to advertising that’s violent and graphic. The problem for firms is figuring out “who’s who” in terms of their personalities.

Marketers have had better luck linking people’s self-concepts to their buying behaviour. Your self-concept is how you see yourself—be it positive or negative. Your ideal self is how you would like to see yourself—whether it’s prettier, more popular, more eco-conscious, or more “goth,” and others’ self-concept, or how you think others see you, also influences your purchase behaviour. Marketing researchers believe people buy products to enhance how they feel about themselves—to get themselves closer to their ideal selves.

The slogan “Be All That You Can Be,” which for years was used by the U.S. Army to recruit soldiers, is an attempt to appeal to the self-concept. Presumably, by joining the U.S. Army, you will become a better version of yourself, which will, in turn, improve your life. Many beauty products and cosmetic procedures are advertised in a way that’s supposed to appeal to the ideal self people seek. All of us want products that improve our lives.

Gender, Age, and Stage of Life

While demographic variables such as income, education, and marital status are important, we will look at gender, age, and stage of life and how they influence purchase decisions. Men and women need and buy different products (Ward & Thuhang, 2007). They also shop differently and in general, have different attitudes about shopping. You know the old stereotypes. Men see what they want and buy it, but women “try on everything and shop ‘til they drop.” There’s some truth to the stereotypes. That’s why you see so many advertisements directed at one sex or the other—beer commercials that air on ESPN and commercials for household products that air on Lifetime. In 2008, women influenced fully two-thirds of all household product purchases, whereas men bought about three-quarters of all alcoholic beverages (Schmitt). The shopping differences between men and women seem to be changing, though. Younger, well-educated men are less likely to believe grocery shopping is a woman’s job and would be more inclined to bargain shop and use coupons if the coupons were properly targeted at them (Hill & Harmon, 2007). One survey found that approximately 45 percent of married men actually like shopping and consider it relaxing.

One study by Resource Interactive, a technology research firm, found that when shopping online, men prefer sites with lots of pictures of products and women prefer to see products online in a lifestyle context—say, a lamp in a living room. Women are also twice as likely as men to use viewing tools such as the zoom and rotate buttons and links that allow them to change the colour of products.

Culture

Culture refers to the shared beliefs, customs, behaviours, and attitudes that characterize a society. Culture is a handed-down way of life and is often considered the broadest influence on a consumer’s behaviour. Your culture prescribes the way in which you should live and has a huge effect on the things you purchase. For example, in Beirut, Lebanon, women can often be seen wearing miniskirts. If you’re a woman in Afghanistan wearing a miniskirt, however, you could face bodily harm or death. In Afghanistan women generally wear burqas, which cover them completely from head to toe. Similarly, in Saudi Arabia, women must wear what’s called an abaya, or long black garment. Interestingly, abayas have become big business in recent years. They come in many styles, cuts, and fabrics and some are encrusted with jewels and cost thousands of dollars.

Even cultures that share many of the same values as the United States can be quite different. Following the meltdown of the financial markets in 2008, countries around the world were pressed by the United States to engage in deficit spending to stimulate the worldwide economy. The plan was a hard sell both to German politicians and to the German people in general. Most Germans don’t own credit cards and running up a lot of debt is something people in that culture generally don’t do. Credit card companies such as Visa, American Express, and MasterCard must understand cultural perceptions about credit.

Subcultures

A subculture is a group of people within a culture who are different from the dominant culture but have something in common with one another such as common interests, vocations or jobs, religions, ethnic backgrounds, and geographic locations. The fastest-growing subculture in the United States consists of people of Hispanic origin, followed by Asian Americans, and African Americans. The purchasing power of U.S. Hispanics continues to grow, exceeding $1 trillion in 20104. Home Depot has launched a Spanish version of its Web site. Walmart is in the process of converting some of its Neighbourhood Markets into stores designed to appeal to Hispanics. The Supermarcado de Walmart stores are located in Hispanic neighbourhoods and feature elements such as cafés serving Latino pastries and coffee and full meat and fish counters (Birchall, 2009). Marketing products based on the ethnicity of consumers is useful but may become harder to do in the future because the boundaries between ethnic groups are blurring.

Care to join the subculture of the “Otherkin”? Otherkins are primarily Internet users who believe they are reincarnations of mythological or legendary creatures—angels, demons, vampires—you name it. To read more about the Otherkins and seven other bizarre subcultures, visit http://www.oddee.com/item_96676.aspx.

Subcultures, such as college students, can develop in response to people’s interests, similarities, and behaviours that allow marketing professionals to design specific products for them. You have probably heard of the hip-hop subculture, people who engage in extreme types of sports such as helicopter skiing or people who play the fantasy game Dungeons and Dragons.

Reference Groups and Opinion Leaders

Reference groups are groups (social groups, work groups, family, or close friends) a consumer identifies with and may want to join. They influence consumers’ attitudes and behaviour. If you have ever dreamed of being a professional player of basketball or another sport, you have an aspirational reference group. That’s why, for example, Nike hires celebrities such as Michael Jordan to pitch the company’s products. There may also be dissociative groups or groups where a consumer does not want to be associated.

Opinion leaders are people with expertise in certain areas. Consumers respect these people and often ask their opinions before they buy goods and services. An information technology (IT) specialist with a great deal of knowledge about computer brands is an example. These people’s purchases often lie at the forefront of leading trends. The IT specialist is probably a person who has the latest and greatest tech products, and his opinion of them is likely to carry more weight with you than any sort of advertisement.

Today’s companies are using different techniques to reach opinion leaders. Network analysis using special software is one way of doing so. Orgnet.com has developed software for this purpose. Orgnet’s software doesn’t mine sites like Facebook and LinkedIn, though. Instead, it’s based on sophisticated techniques that unearthed the links between Al Qaeda terrorists. Explains Valdis Krebs, the company’s founder: “Pharmaceutical firms want to identify who the key opinion leaders are. They don’t want to sell a new drug to everyone. They want to sell to the 60 key oncologists” (Campbell, 2004).

Family

Most market researchers consider a person’s family to be one of the most important influences on their buying behaviour. Like it or not, you are more like your parents than you think, at least in terms of your consumption patterns. Many of the things you buy and don’t buy are a result of what your parents bought when you were growing up. Products such as the brand of soap and toothpaste your parents bought and used, and even the “brand” of politics they leaned toward (Democratic or Republican) are examples of the products you may favour as an adult.

Companies are interested in which family members have the most influence over certain purchases. Children have a great deal of influence over many household purchases. For example, in 2003 nearly half (47 percent) of nine- to seventeen-year-olds were asked by parents to go online to find out about products or services, compared to 37 percent in 2001. IKEA used this knowledge to design their showrooms. The children’s bedrooms feature fun beds with appealing comforters so children will be prompted to identify and ask for what they want8.

Marketing to children has come under increasing scrutiny. Some critics accuse companies of deliberately manipulating children to nag their parents for certain products. For example, even though tickets for Hannah Montana concerts ranged from hundreds to thousands of dollars, the concerts often still sold out. However, as one writer put it, exploiting “pester power” is not always ultimately in the long-term interests of advertisers if it alienates kids’ parents (Waddell, 2009).

Conducting a SWOT Analysis

Based on the situation analysis, organizations analyze their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, or conduct what’s called a SWOT analysis. Strengths and weaknesses are internal factors and are somewhat controllable. For example, an organization’s strengths might include its brand name, efficient distribution network, reputation for great service, and strong financial position. A firm’s weaknesses might include a lack of awareness of its products in the marketplace, a lack of human resources talent, and a poor location. Opportunities and threats are factors that are external to the firm and largely uncontrollable. Opportunities might entail the international demand for the type of products the firm makes, few competitors, and favourable social trends such as people living longer. Threats might include a bad economy, high interest rates that increase a firm’s borrowing costs, and an ageing population that makes it hard for the business to find workers.

You can conduct a SWOT analysis of yourself to help determine your competitive advantage. Perhaps your strengths include strong leadership abilities and communication skills, whereas your weaknesses include a lack of organization. Opportunities for you might exist in specific careers and industries; however, the economy and other people competing for the same position might be threats. Moreover, a factor that is a strength for one person (say, strong accounting skills) might be a weakness for another person (poor accounting skills). The same is true for businesses. See Figure 10.8: “Elements of a SWOT analysis” for an illustration of some of the factors examined in a SWOT analysis.

The easiest way to determine if a factor is external or internal is to take away the company, organization, or individual and see if the factor still exists. Internal factors such as strengths and weaknesses are specific to a company or individual, whereas external factors such as opportunities and threats affect multiple individuals and organizations in the marketplace. For example, if you are doing a situation analysis on PepsiCo and are looking at the weak economy, take PepsiCo out of the picture and see what factors remain. If the factor—the weak economy—is still there, it is an external factor. Even if PepsiCo hadn’t been around in 2008–2009, the weak economy reduced consumer spending and affected a lot of companies.

Utilizing Data Analytics

In the sports industry, analytics is used to build on a sports team’s marketing strategies by providing teams with a better understanding of their fans and customers. By analyzing data from sources such as ticket sales, social media, and online engagement, teams can gain insights into their customers’ behaviours and preferences. This information can then be used to tailor marketing campaigns and improve the overall customer experience, ultimately leading to increased revenue and fan engagement. Therefore successful sports organizations use data analytics to understand their fans in great detail to build deeper long-term relationships and add value.