10.5 Step 3: Marketing Program (Marketing Mix, Marketing Strategies, 4 P’s)

After completing Step 2, your next step is developing and implementing a marketing program designed to reach your identified target audience. As the graphic below shows, this program involves a combination of tools called the marketing mix, often referred to as the “four P’s” of marketing:

- Developing a product/service that meets the needs of the target market

- Setting a price for the product/service

- Distributing the product/service—getting it to a place where customers can buy it

- Promoting the product/service—informing potential buyers about it

Product/Service

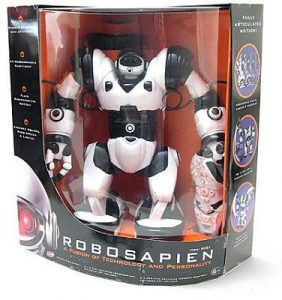

The development of Robosapien was a bit unusual for a company that was already active in its market.[12] Generally, product ideas come from people within the company who understands its customers’ needs. Internal engineers are then challenged to design the product. In the case of Robosapien, the creator, Mark Tilden, had conceived and designed the product before joining Wow Wee Toys. The company gave him the opportunity to develop the product for commercial purposes, and Tilden was brought on board to oversee the development of Robosapien into a product that satisfied Wow Wee’s commercial needs.

Robosapien is not a “kid’s toy,” though kids certainly love its playful personality. It’s a home-entertainment product that appeals to a broad audience—children, young adults, older adults, and even the elderly. It’s a big gift item, and it has developed a following of techies and hackers who take it apart, tinker with it, and even retrofit it with such features as cameras and ice skates.

Conducting Marketing Research

Before settling on a strategy for Robosapien, the marketers at Wow Wee did some homework. First, to zero in on their target market, they had to find out what various people thought of the product. More precisely, they needed answers to questions like the following:

- Who are our potential customers?

- What do they like about Robosapien? What would they change?

- How much are they willing to pay for it?

- Where will they expect to buy it?

- How can we distinguish it from competing products?

- Will enough people buy Robosapien to return a reasonable profit for the company?

The last question would be left up to Wow Wee management, but, given the size of the investment needed to bring Robosapien to market, Wow Wee couldn’t afford to make the wrong decision. Ultimately, the company was able to make an informed decision because its marketing team provided answers to key questions through marketing research—the process of collecting and analyzing the data that are relevant to a specific marketing situation. This data had to be collected in a systematic way. Market research seeks two types of data:

- Marketers generally begin by looking at secondary data—information already collected, whether by the company or by others, that pertains to the target market.

- With secondary data in hand, they’re prepared to collect primary data—newly collected information that addresses specific questions.

Secondary data can come from inside or outside the organization. Internally available data includes sales reports and other information on customers. External data can come from a number of sources. Statistics Canada, for example, posts demographic information on Canadian households (such as age, income, education, and number of members), both for the country as a whole and for specific geographic areas.

Population data from U.S. Census Bureau (the American equivalent to Statistics Canada), helped Wow Wee estimate the size of its potential U.S. target market. Other secondary data helped the firm assess the size of foreign markets in regions around the world, such as Europe, the Middle East, Latin America, Asia, and the Pacific Rim. This data helped position the company to sell Robosapien in eighty-five countries, including Canada, England, France, Germany, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Japan.

Using secondary data that is already available (and free) is a lot easier than collecting your own information. Unfortunately, however, secondary data didn’t answer all the questions that Wow Wee was asking in this particular situation. To get these answers, the marketing team had to conduct primary research, working directly with members of their target market. First, they had to decide exactly what they needed to know, then determine who to ask and what methods would be most effective in gathering the information.

We know what they wanted to know—we’ve already listed example questions. As for whom to talk to, they randomly selected representatives from their target market. There is a variety of tools for collecting information from these people, each of which has its advantages and disadvantages. To understand the marketing-research process fully, we need to describe the most common of these tools:

- Surveys. Sometimes marketers mail questionnaires to members of the target market. The process is time-consuming and the response rate is generally low. Online surveys are easier to answer and so get better response rates than other approaches.

- Personal interviews. Though time-consuming, personal interviews not only let you talk with real people but also let you demonstrate the product. You can also clarify answers and ask open-ended questions.

- Focus groups. With a focus group, you can bring together a group of individuals (perhaps six to ten) and ask them questions. A trained moderator can explain the purpose of the group and lead the discussion. If sessions are run effectively, you can come away with valuable information about customer responses to both your product and your marketing strategy.

Wow Wee used focus groups and personal interviews because both approaches had the advantage of allowing people to interact with Robosapien. In particular, focus-group sessions provided valuable opinions about the product, proposed pricing, distribution methods, and promotion strategies.

Researching your target market is necessary before you launch a new product, but the benefits of marketing research don’t extend merely to brand-new products. Companies also use it when they’re deciding whether or not to refine an existing product or develop a new marketing strategy for an existing product. PepsiCo Canada, for example, relaunched the Doritos Ketchup chip in 2014 as a limited-time-only retro flavour and it was a tremendous success. Because of this positive customer feedback, instead of looking for a new chip flavour the following year, they announced that they would continue the ketchup version, accompanied it with a ‘hold on to your phone’ contest and app that awarded winners with a years-supply of the chips, as well as the limited availability of a dozen ‘ketchup roses’ during Valentine’s season.[13]

Branding

Armed with positive feedback from their research efforts, the Wow Wee team was ready for the next step: informing buyers—both consumers and retailers—about their product. They needed a brand—some word, letter, sound, or symbol that would differentiate their product from similar products on the market. They chose the brand name Robosapien, hoping that people would get the connection between homo sapiens (the human species) and Robosapien (the company’s coinage for its new robot “species”). To prevent other companies from coming out with their own “Robosapiens,” they took out a trademark: a symbol, word, or words legally registered or established by use as representing a company or product. Trademarking requires registering the name with the Canadian Intellectual Property Office. Though this approach—giving a unique brand name to a particular product—is a bit unusual, it isn’t unprecedented. Kraft Foods, for example, established a separate brand for Nabob Coffee, and Labatt Brewing Company sells beer under the brand name Alexander Keith’s. Note, however, that the more common approach, which is taken by such companies as Dare Foods, McCain Foods and Lululemon Athletica, calls for marketing all the products made by a company under the company’s brand name.

Branding Strategies

Companies can adopt one of three major strategies for branding a product:

- With private branding (or private labelling), a company makes a product and sells it to a retailer who in turn resells it under its own name. A soft-drink maker, for example, might make cola for Walmart to sell as its Great Value Cola.

- With generic branding, the maker attaches no branding information to a product except a description of its contents. Customers are often given a choice between a brand-name prescription drug or a cheaper generic drug with the same formula.

- With manufacturer branding, a company sells one or more products under its own brand name(s). Adopting a multi-product branding approach, it sells all its products under one brand name (generally the company name). Using a multi-branding approach, it will assign different brand names to different products covering different segments of the market. Automakers generally use multi-branding. For example, the Volkswagen group of brands also includes Audi, Bentley, and even Lamborghini.

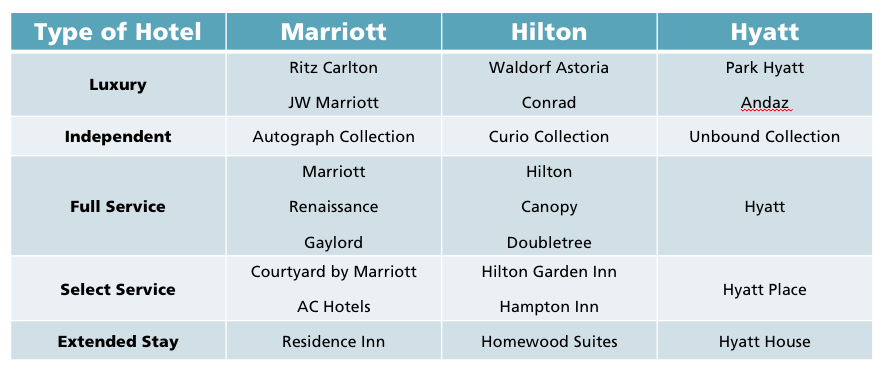

Branding is used in hotels to allow chains (Marriott, Hyatt, Hilton) to offer hotel brands that meet various customers’ travel needs while still maintaining their loyalty to the chain. The same customer who would choose an Extended Stay hotel with a full kitchen when on a long-term assignment might stay at a convention hotel when attending a trade show and then stay in a resort property when travelling with their family. By segmenting different types of hotel locations, amenities, room sizes and décor, hotel chains can meet the needs of a wide variety of travellers. In the past decade, “soft” branding has become common to allow unique hotels to take advantage of being part of a chain reservation system and loyalty program. For example, Marriott has over 100 affiliated independent hotels in its Autograph Collection.[14]

Loyalty programs are heavily used in the hospitality industry, especially airlines and hotels, as part of their Customer Relationship Management programs. Some examples of popular Canadian Loyalty programs include Air Miles, Canadian Tire Rewards, Aeroplan, HBC Rewards and PC Optimum. Airline loyalty programs such as Air Canada Loyalty, are often targeted to high-value business travellers with less price sensitivity. They achieve loyalty status and perks while travelling as well as earning points to use for personal travel rewards. Once a loyalty program member obtains elite status with significant associated perks such as guaranteed room availability, airport club lounge access, etc., the customer is much less likely to use other brands.

Packaging and Labelling

Packaging can influence a consumer’s decision to buy a product or pass it up. Packaging gives customers a glimpse of the product, and it should be designed to attract their attention, with consideration given to colour choice, style of lettering, and many other details. Labelling not only identifies the product but also provides information on the package contents: who made it and where or what risks are associated with it (such as being unsuitable for small children).

How has Wow Wee handled the packaging and labelling of Robosapien? The robot is fourteen inches tall and is also fairly heavy (about seven pounds), and because it’s made out of plastic and has movable parts, it’s breakable. The easiest, and least expensive, way of packaging it would be to put it in a square box of heavy cardboard and pad it with Styrofoam. This arrangement would not only protect the product from damage during shipping but also make the package easy to store. However, it would also eliminate any customer contact with the product inside the box (such as seeing what it looks like). Wow Wee, therefore, packages Robosapien in a container that is curved to his shape and has a clear plastic front that allows people to see the whole robot. Why did Wow Wee go to this much trouble and expense? Like so many makers of so many products, it has to market the product while it’s still in the box.

Meanwhile, the labelling on the package details some of the robot’s attributes. The name is highlighted in big letters above the descriptive tagline “A fusion of technology and personality.” On the sides and back of the package are pictures of the robot in action with such captions as “Dynamic Robotics with Attitude” and “Awesome Sounds, Robo-Speech & Lights.” These colourful descriptions are conceived to entice the consumer to make a purchase because its product features will satisfy some need or want.

Packaging can serve many purposes. The Robosapien package attracts attention to the product’s features. For other products, packaging serves a more functional purpose. Kraft Foods packages some of its snacks— Oreos and Chips Ahoy, and —in “100 Calorie Packs.” The packaging makes life simpler for people who are keeping track of calories.

Understanding the Product Life Cycle

Once a product is created and introduced in the marketplace, the offering must be managed effectively for the customer to receive value from it. Only if this is done will the product’s producer achieve its profit objectives and be able to sustain the offering in the marketplace. The process involves making many complex decisions, especially if the product is being introduced in global markets. Before introducing products in global markets, an organization must evaluate and understand factors in the external environment, including laws and regulations, the economy and stage of economic development, the competitors and substitutes, cultural values, and market needs. Companies also need expertise to successfully launch products in foreign markets. Given many possible constraints in international markets, companies might initially introduce a product in limited areas abroad. Other organizations, such as Coca-Cola, decide to compete in markets worldwide1.

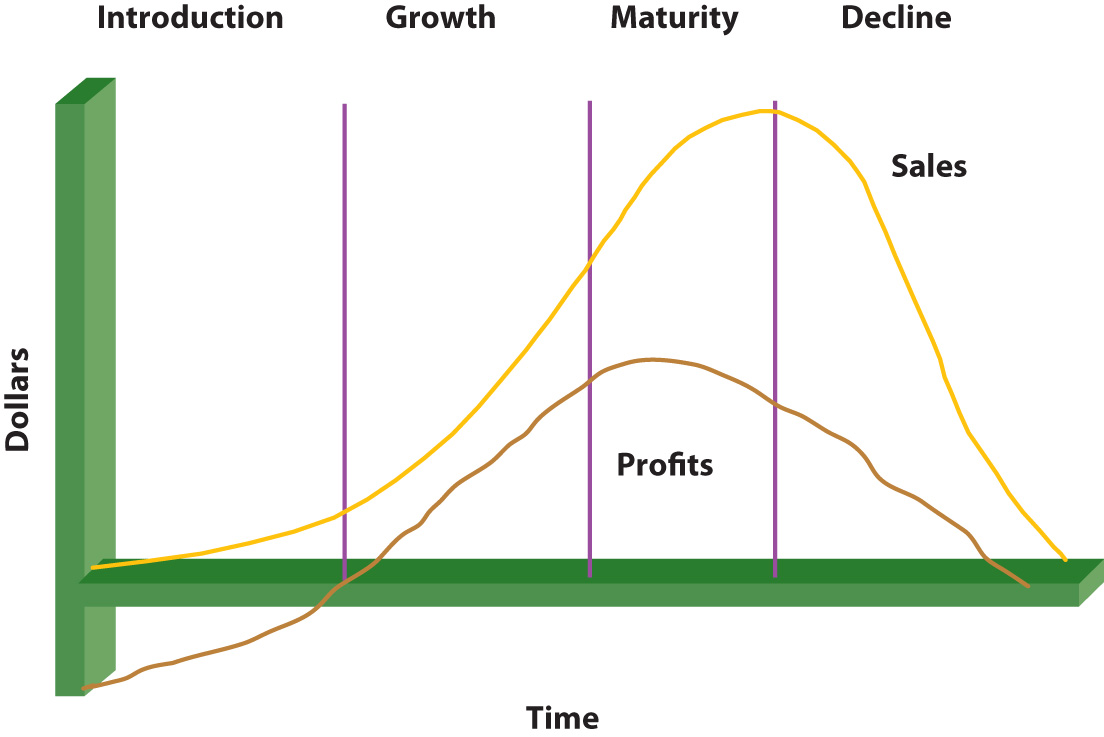

The product life cycle (PLC) includes the stages the product goes through after development, from introduction to the end of the product. Just as children go through different phases in life (toddler, elementary school, adolescent, young adult, and so on), products and services also age and go through different stages. The PLC is a beneficial tool that helps marketers manage the stages of a product’s acceptance and success in the marketplace, beginning with the product’s introduction, its growth in market share, maturity, and possible decline in market share. Other tools such as the Boston Consulting Group matrix and the General Electric approach (see Chapter 2 “Strategic Planning” for discussion) may also be used to manage and make decisions about what to do with products. For example, when a market is no longer growing but the product is doing well (cash cow in the BCG approach), the company may decide to use the money from the cash cow to invest in other products they have rather than continuing to invest in the product in a no-growth market.

The product life cycle can vary for different products and different product categories. Figure 10.5 “Life Cycle” illustrates an example of the product life cycle, showing how a product can move through four stages. However, not all products go through all stages and the length of a stage varies. For example, some products never experience market share growth and are withdrawn from the market.

Other products stay in one stage longer than others. For example, in 1992, PepsiCo introduced a product called Clear Pepsi, which went from introduction to decline very rapidly. By contrast, Diet Coke entered the growth market soon after its introduction in the early 1980s and then entered (and remains in) the mature stage of the product life cycle. New computer products and software and video games often have limited life cycles, whereas product categories such as diamonds and durable goods (kitchen appliances) generally have longer life cycles. How a product is promoted, priced, distributed, or modified can also vary throughout its life cycle. Let’s now look at the various product life cycle stages and what characterizes each.

The Introduction Stage

The first stage in a product’s life cycle is the introduction stage. The introduction stage is the same as commercialization, or the last stage of the new product development process. Marketing costs are typically higher in this stage than in other stages. As an analogy, think about the amount of fuel a plane needs for takeoff relative to the amount it needs while in the air. Just as an airplane needs more fuel for takeoff, a new product or service needs more funds for introduction into the marketplace. Communication (promotion) is needed to generate awareness of the product and persuade consumers to try it, and placement alternatives and supply chains are needed to deliver the product to the customers. Profits are often low in the introductory stage due to the research and development costs and the marketing costs necessary to launch the product.

The Growth Stage

If a product is accepted by the marketplace, it enters the growth stage of the product life cycle. The growth stage is characterized by increasing sales, more competitors, and higher profits. Unfortunately for the firm, the growth stage attracts competitors who enter the market very quickly. For example, when Diet Coke experienced great success, Pepsi soon entered with Diet Pepsi. You’ll notice that both Coca-Cola and Pepsi have similar competitive offerings in the beverage industry, including their own brands of bottled water, juice, and sports drinks. As additional customers begin to buy the product, manufacturers must ensure that the product remains available to customers or run the risk of them buying competitors’ offerings. For example, the producers of video game systems such as Nintendo’s Wii could not keep up with consumer demand when the product was first launched. Consequently, some consumers purchased competing game systems such as Microsoft’s Xbox.

The Maturity Stage

After many competitors enter the market and the number of potential new customers declines, the sales of a product typically begin to level off. This indicates that a product has entered the maturity stage of its life cycle. Most consumer products are in the mature stage of their life cycle; their buyers are repeat purchasers versus new customers. Intense competition causes profits to fall until only the strongest players remain. The maturity stage lasts longer than other stages. Quaker Oats and Ivory Soap are products in the maturity stage—they have been on the market for over one hundred years.

The Decline Stage

When sales decrease and continue to drop to lower levels, the product has entered the decline stage of the product life cycle. In the decline stage, changes in consumer preferences, technological advances, and alternatives that satisfy the same need can lead to a decrease in demand for a product. How many of your fellow students do you think have used a typewriter, adding machine, or slide rule? Computers replaced the typewriter and calculators replaced adding machines and the slide rule. Ask your parents about eight-track tapes, which were popular before cassette tapes, which were popular before CDs, which were popular before MP3 players and Internet radio. Some products decline slowly. Others go through a rapid level of decline. Many fads and fashions for young people tend to have very short life cycles and go “out of style” very quickly. (If you’ve ever asked your parents to borrow clothes from the 1990s, you may be amused at how much the styles have changed.) Similarly, many students don’t have landline phones or VCR players and cannot believe that people still use “outdated” devices. Some outdated devices, like payphones, disappear almost completely as they become obsolete.

Price

Before pricing a product, an organization must determine its pricing objectives. In other words, what does the company want to accomplish with its pricing? Companies must also estimate demand for the product or service, determine the costs, and analyze all factors (e.g., competition, regulations, and economy) affecting price decisions. Then, to convey a consistent image, the organization should choose the most appropriate pricing strategy and determine policies and conditions regarding price adjustments. The basic steps in the pricing framework are shown in Figure 10.17: “The Pricing Framework”.

The Firm’s Pricing Objectives

Different firms want to accomplish different things with their pricing strategies. For example, one firm may want to capture market share, another may be solely focused on maximizing its profits, and another may want to be perceived as having products with prestige. Some examples of different pricing objectives companies may set include profit-oriented objectives, sales-oriented objectives, and status quo objectives.

Earning a Targeted Return on Investment (ROI)

ROI, or return on investment, is the amount of profit an organization hopes to make given the amount of assets, or money, it has tied up in a product. ROI is a common pricing objective for many firms. Companies typically set a certain percentage, such as 10 percent, for ROI in a product’s first year following its launch. So, for example, if a company has $100,000 invested in a product and is expecting a 10 percent ROI, it would want the product’s profit to be $10,000.

Maximizing Profits

Many companies set their prices to increase their revenues as much as possible relative to their costs. However, large revenues do not necessarily translate into higher profits. To maximize its profits, a company must also focus on cutting costs or implementing programs to encourage customer loyalty.

In weak economic markets, many companies manage to cut costs and increase their profits, even though their sales are lower. How do they do this? The Gap cut costs by doing a better job of controlling its inventory. The retailer also reduced its real estate holdings to increase its profits when its sales were down during the latest economic recession. Other firms such as Dell, Inc., cut jobs to increase their profits. Meanwhile, Walmart tried to lower its prices so as to undercut its competitors’ prices to attract more customers. After it discovered that wealthier consumers who didn’t usually shop at Walmart before the recession were frequenting its stores, Walmart decided to upgrade some of its offerings, improve the checkout process, and improve the appearance of some of its stores to keep these high-end customers happy and enlarge its customer base. Other firms increased their prices or cut back on their marketing and advertising expenses. A firm has to remember, however, that prices signal value. If consumers do not perceive that a product has a high degree of value, they probably will not pay a high price for it. Furthermore, cutting costs cannot be a long-term strategy if a company wants to maintain its image and position in the marketplace.

Maximizing Sales

Maximizing sales involves pricing products to generate as much revenue as possible, regardless of what it does to a firm’s profits. When companies are struggling financially, they sometimes try to generate cash quickly to pay their debts. They do so by selling off inventory or cutting prices temporarily. Such cash may be necessary to pay short-term bills, such as payroll. Maximizing sales is typically a short-term objective since profitability is not considered.

Maximizing Market Share

Some organizations try to set their prices in a way that allows them to capture a larger share of the sales in their industries. Capturing more market share doesn’t necessarily mean a firm will earn higher profits, though. Nonetheless, many companies believe capturing a maximum amount of market share is downright necessary for their survival. In other words, they believe if they remain a small competitor they will fail. Firms in the cellular phone industry are an example. The race to be the biggest cell phone provider has hurt companies like Motorola. Motorola holds only 10 percent of the cell phone market, and its profits on the product lines are negative.

Pricing Strategies

There are various pricing strategies for products and services that typically depend upon where a product is on the Product Life Cycle. Below we have outlined a few pricing strategies for the different stages of the Product Life Cycle.

The Introduction Stage

Product pricing strategies in the introductory stage can vary depending on the type of product, competing products, the extra value the product provides consumers versus existing offerings, and the costs of developing and producing the product. Organizations want consumers to perceive that a new offering is better or more desirable than existing products. Two strategies that are widely used in the introductory stage are penetration pricing and skimming. A penetration pricing strategy involves using a low initial price to encourage many customers to try a product. The organization hopes to sell a high volume in order to generate substantial revenues. New varieties of cereals, fragrances of shampoo, scents of detergents, and snack foods are often introduced at low initial prices. Seldom does a company utilize a high price strategy with a product such as this. The low initial price of the product is often combined with advertising, coupons, samples, or other special incentives to increase awareness of the product and get consumers to try it.

A company uses a skimming pricing strategy, which involves setting a high initial price for a product, to more quickly recoup the investment related to its development and marketing. The skimming strategy attracts the top, or high end, of the market. Generally, this market consists of customers who are not as price-sensitive or who are early adopters of products. Firms that produce electronic products such as DVRs, plasma televisions, and digital cameras set their prices high in the introductory stage. However, the high price must be consistent with the nature of the product as well as the other marketing strategies being used to promote it. For example, engaging in more personal selling to customers, running ads targeting specific groups of customers, and placing the product in a limited number of distribution outlets are likely to be strategies firms use in conjunction with a skimming approach.

The Growth Stage

The price of the product itself typically remains at about the same level during the growth stage, although some companies reduce their prices slightly to attract additional buyers and meet the competitors’ prices. Companies hope by increasing their sales, they also improve their profits.

The Maturity Stage

Companies may decrease the price of mature products to counter the competition. However, they must be careful not to get into “price wars” with their competitors and destroy all the profit potential of their markets, threatening a firm’s survival. Intel and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) have engaged in several price wars with regard to their microprocessors. Likewise, Samsung added features and lowered the price on its Instinct mobile phone, engaging in a price war with Apple’s iPhone. With the weakened economy, many online retailers engaged in price wars during the 2008 holiday season by cutting prices on their products and shipping costs; they repeated this price war strategy in 2011. Although large organizations such as Amazon.com can absorb shipping costs, price wars often hurt smaller retailers.

The Decline Stage

If a product enters into the decline stage organizations are given very few options when it comes to pricing. Harvesting the product entails gradually reducing all costs spent on it, including investments made in the product and marketing costs. By reducing these costs, the company hopes that the profits from the product will increase until their inventory runs out. Another option for the company is divesting (dropping or deleting) the product from its offerings. The company might choose to sell the brand to another firm or simply reduce the price drastically in order to get rid of all remaining inventory.

Place

In the past few decades, organizations have begun taking a more holistic look at their marketing channels. Instead of looking at only the firms that sell and promote their products, they have begun looking at all the organizations that figure into any part of the process of producing, promoting, and delivering an offering to its user. All these organizations are considered part of the offering’s supply chain.

For instance, the supply chain includes producers of the raw materials that go into a product. If it’s a food product, the supply chain extends back through the distributors all the way to the farmers who grew the ingredients and the companies from which the farmers purchased the seeds, fertilizer, or animals. A product’s supply chain also includes transportation companies such as railroads that help physically move the product and companies that build Web sites for other companies. If a software maker hires a company in India to help it write a computer program, the Indian company is part of the partner’s supply chain. These types of firms aren’t considered channel partners because it’s not their job to actively sell the products being produced. Nonetheless, they all contribute to a product’s success or failure.

Firms are constantly monitoring their supply chains and tinkering with them so they’re as efficient as possible. This process is called supply chain management. Supply chain management is challenging. If done well, it’s practically an art.

Types of Channel Partners

Let’s now look at the basic types of channel partners. To help you understand the various types of channel partners, we will go over the most common types of intermediaries. The two types you hear about most frequently are wholesalers and retailers. Keep in mind, however, that the categories we discuss in this section are just that—categories. In recent years, the lines between wholesalers, retailers, and producers have begun to blur considerably. Microsoft is a producer of goods, but in 2009 it began opening up its own retail stores to sell products to consumers, much as Apple has done (Lyons). As you will learn later in the chapter, Walmart and other large retailers now produce their own store brands and sell them to other retailers. Similarly, many producers have outsourced their manufacturing, and although they still call themselves manufacturers, they act more like wholesalers. Wherever organizations see an opportunity, they are beginning to take it, regardless of their positions in marketing channels.

Wholesalers

Wholesalers obtain large quantities of products from producers, store them, and break them down into cases and other smaller units more convenient for retailers to buy, a process called “breaking bulk.” Wholesalers get their name from the fact that they resell goods “whole” to other companies without transforming the goods. If you are trying to stock a small electronics store, you probably don’t want to purchase a truckload of iPods. Instead, you probably want to buy a smaller assortment of iPods as well as other merchandise. Via wholesalers, you can get the assortment of products you want in the quantities you want. Some wholesalers carry a wide range of different products. Others carry narrow ranges of products.

Most wholesalers “take title” to goods—or own them until purchased by other sellers. Wholesalers such as these assume a great deal of risk on the part of companies further down the marketing channel as a result. For example, if the iPods you plan to purchase are stolen during shipment, damaged, or become outdated because a new model has been released, the wholesaler suffers the loss—not you. Electronic products, in particular, become obsolete very quickly. Think about the cell phone you owned just a couple of years ago. Would you want to have to use it today?

Merchant Wholesalers

Merchant wholesalers are wholesalers that take title to the goods. They are also sometimes referred to as distributors, dealers, and jobbers. The category includes both full-service wholesalers and limited-service wholesalers. Full-service wholesalers perform a broad range of services for their customers, such as stocking inventories, operating warehouses, supplying credit to buyers, employing salespeople to assist customers, and delivering goods to customers. Maurice Sporting Goods is a large North American full-service wholesaler of hunting and fishing equipment. The firm’s services include helping customers figure out which products to stock, how to price them, and how to display them1.

Limited-service wholesalers offer fewer services to their customers but lower prices. They might not offer delivery services, extend their customers’ credit, or have sales forces that actively call sellers. Cash-and-carry wholesalers are an example. Small retailers often buy from cash-and-carry wholesalers to keep their prices as low as big retailers that get large discounts because of the huge volumes of goods they buy.

Drop shippers are another type of limited-service wholesaler. Although drop shippers take title to the goods, they don’t actually take possession of them or handle them, oftentimes because they deal with goods that are large or bulky. Instead, they earn a commission by finding sellers and passing their orders along to producers, who then ship them directly to the sellers. Mail-order wholesalers sell their products using catalogues instead of sales forces and then ship the products to buyers. Truck jobbers (or truck wholesalers) actually store products, which are often highly perishable (e.g., fresh fish), on their trucks. The trucks make the rounds to customers, who inspect and select the products they want straight off the trucks.

Rack jobbers sell specialty products, such as books, hosiery, and magazines that they display on their own racks in stores. Rack jobbers retain the title to the goods while the merchandise is in the stores for sale. Periodically, they take count of what’s been sold off their racks and then bill the stores for those items.

Brokers

Brokers, or agents, don’t purchase or take title to the products they sell. Their role is limited to negotiating sales contracts for producers. Clothing, furniture, food, and commodities such as lumber and steel are often sold by brokers. They are generally paid a commission for what they sell and are assigned to different geographical territories by the producers with whom they work. Because they have excellent industry contacts, brokers and agents are “go-to” resources for both consumers and companies trying to buy and sell products.

The most common form of agents and brokers consumers encounter are in real estate. A real estate agent represents, or acts for, either the buyer or the seller. The listing agent is contacted by the homeowner who wants to sell and then puts the house on the market. The buyer also contacts an agent who shows the buyer a number of houses. If there is a house that the buyer wants to purchase, the agent calls the listing agent and the price is negotiated. In some states, the buyer’s agent is a legal representative of the seller, unless a buyer’s agent agreement is signed, which is something to keep in mind when you are the buyer. Agents work for brokers, who act as a sort of head agent and market the company’s services while making sure that all of the legal requirements are met.

Manufacturers’ Sales Offices or Branches

Manufacturers’ sales offices or branches are selling units that work directly for manufacturers. These are found in business-to-business settings. For example, Konica-Minolta Business Systems (KMBS) has a system of sales branches that sell KMBS printers and copiers directly to companies that need them. As a consumer, it would be rare for you to interact directly with a manufacturer through a sales office because in those instances, such as with Apple stores and Nike stores, these are considered retail outlets.

Retailers

Retailers buy products from wholesalers, agents, or distributors and then sell them to consumers. Retailers vary by the types of products they sell, their sizes, the prices they charge, the level of service they provide consumers, and the convenience or speed they offer. You are familiar with many of these types of retailers because you have purchased products from them. We mentioned Nike and Apple as examples of companies that make and sell products directly to consumers, but in reality, Nike and Apple contract manufacturing to other companies. They may design the products, but they actually buy the finished goods from others.

Supermarkets, or grocery stores, are self-service retailers that provide a full range of food products to consumers, as well as some household products. Supermarkets can be high, medium, or low range in terms of the prices they charge and the service and variety of products they offer. Whole Foods and Central Market are grocers that offer a wide variety of products, generally at higher prices. Midrange supermarkets include stores like Albertsons and Kroger. Aldi and Sack ’n Save are examples of supermarkets with a limited selection of products and services but low prices. Drugstores specialize in selling over-the-counter medications, prescriptions, and health and beauty products and offer services such as photo development.

Convenience stores are miniature supermarkets. Many of them sell gasoline and are open twenty-four hours a day. Often they are located on corners, making it easy and fast for consumers to get in and out. Some of these stores contain fast-food franchises like Church’s Chicken and Jack in the Box. Consumers pay for convenience in the form of higher markups on products. In Europe, as well as in rural parts of the United States, you’ll find convenience stores that offer fresh meat and produce.

Specialty stores sell a certain type of product, but they usually carry a deep line of it. Zales, which sells jewelry, and Williams-Sonoma, which sells an array of kitchen and cooking-related products, are examples of specialty stores. The personnel who work in specialty stores are usually knowledgeable and often provide customers with a high level of service. Specialty stores vary by size. Many are small. However, in recent years, giant specialty stores called category killers have emerged. A category killer sells a high volume of a particular type of product and, in doing so, dominates the competition, or “category.” PETCO and PetSmart are category killers in the retail pet-products market. Best Buy is a category killer in the electronics-product market. Many category killers are struggling themselves as shoppers for their products are moving to the Web or to discount department stores.

Department stores, by contrast, carry a wide variety of household and personal types of merchandise such as clothing and jewelry. Many are chain stores. The prices department stores charge range widely, as does the level of service shoppers receive. Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Nordstrom sell expensive products and offer extensive personal service to customers. The prices department stores such as JCPenney, Sears, and Macy’s charge are midrange, as is the level of service shoppers receive. Walmart, Kmart, and Target are discount department stores with cheaper goods and a limited amount of service. As mentioned earlier, these discount department stores are a real threat to category killers, especially in the form of a superstore.

Superstores are oversized department stores that carry a broad array of general merchandise as well as groceries. Banks, hair and nail salons, and restaurants such as Starbucks are often located within these stores for the convenience of shoppers. You have probably shopped at a SuperTarget or a huge Walmart with offerings such as these. Superstores are also referred to as hypermarkets and supercenters.

Warehouse clubs are supercenters that sell products at a discount. They require people who shop with them to become members by paying an annual fee. Costco and Sam’s Club are examples. Off-price retailers are stores that sell a variety of discount merchandise that consists of seconds, overruns, and the previous season’s stock other stores have liquidated. Big Lots, Ross Dress for Less, and dollar stores are off-price retailers.

Outlet stores were a new phenomenon at the end of the last century. These were discount retailers that operated under the brand name of a single manufacturer, selling products that couldn’t be sold through normal retail channels due to mistakes made in manufacturing. Often located in rural areas but along interstate highways, these stores had lower overhead than similar stores in big cities due to lower rent and lower employee salaries. But due to the high popularity of the stores, demand far outstripped the supply of mistakes. Most outlet malls are now selling first-quality products only, perhaps at a discount.

Online retailers can fit into any of the previous categories; indeed, most traditional stores also have an online version. You can buy from JCPenney.com, Walmart.com, BigLots.com, and so forth. There are also stores, like O.co (formerly called Overstock.com) that operate only on the Web.

Used retailers are retailers that sell used products. Online versions, like eBay and Craigslist, sell everything from used airplanes to clothing. Traditional stores with a physical presence that sell used products include Half-Priced Books and clothing consignment or furniture stores like Amelia’s Attic. Note that in consignment stores, the stores do not take title to the products but only retail them for the seller.

A new type of retail store that turned up in the last few years is the pop-up store. Pop-up stores are small temporary stores. They can be kiosks or temporarily occupy unused retail space. The goal is to create excitement and “buzz” for a retailer that then drives customers to their regular stores. In 2006, JCPenney created a pop-up store in Times Square for a month. Kate Coultas, a spokesperson for JCPenney, said the store got the attention of Manhattan’s residents. Many hadn’t been to a JCPenney store in a long time. “It was a real dramatic statement,” Coultas says. “It kind of had a halo effect” on the company’s stores in the surrounding boroughs of New York City (Austin, 2009). Most commonly, though, pop-up stores are used for seasonal sales, such as a costume store before Halloween or the Hillshire Farms sausage and cheese shops you see at the mall just before Christmas.

Not all retailing goes on in stores, however. Nonstore retailing—retailing not conducted in stores—is a growing trend. Online retailing; party selling; selling to consumers via television, catalogues, and vending machines; and telemarketing are examples of nonstore retailing. These are forms of direct marketing. Companies that engage in direct marketing communicate with consumers and urge them to contact their firms directly to buy products.

A great deal is involved in getting a product to the place in which it is ultimately sold. If you’re a fast-food retailer, for example, you’ll want your restaurants to be in high-traffic areas to maximize your potential business. If your business is selling beer, you’ll want it to be offered in bars, restaurants, grocery stores, convenience stores, and even stadiums. Placing a product in each of these locations requires substantial negotiations with the owners of the space, and often the payment of slotting fees, an allowance paid by the manufacturer to secure space on store shelves.

Retailers are marketing intermediaries that sell products to the eventual consumer. Without retailers, companies would have a much more difficult time selling directly to individual consumers, no doubt at a substantially higher cost. The most common types of retailers are summarized in the Figure below. You will likely recognize many of the examples provided. It is important to note that many retailers do not fit neatly into only one category. For example, Walmart, which began as a discount store, has added groceries to many of its outlets, also placing it in competition with supermarkets.

Promotion

Your promotion mix—the means by which you communicate with customers—may include advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, and publicity. These are all tools for telling people about your product and persuading potential customers to buy it. Before deciding on an appropriate promotional strategy, you should consider a few questions:

- What’s the main purpose of the promotion?

- What is my target market?

- Which product features should I emphasize?

- How much can I afford to invest in a promotion campaign?

- How do my competitors promote their products?

- Which stage is my product in on the Product Life Cycle?

Promotional Tools

We’ll now examine each of the elements that can go into the promotion mix— advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, and publicity.

Advertising

Advertising is paid, non-personal communication designed to create an awareness of a product or company. Ads are everywhere—in print media (such as newspapers, magazines, mailers), on billboards, in broadcast media (radio and TV), and, increasingly, online using search engine optimization techniques. It’s hard to escape the constant barrage of advertising messages; it’s estimated that the average consumer is confronted by about 5,000 ad messages each day (compared with about 500 ads a day in the 1970s).[18] For this very reason, ironically, ads aren’t as effective as they used to be. Because we’ve learned to tune them out, companies now have to come up with innovative ways to get through to potential customers. A New York Times article[19] claims that “anywhere the eye can see, it’s likely to see an ad.” Subway cars are plastered with ads for cell phone companies. Restaurant placemats are decorated with ads, and social media feeds are peppered with ‘suggested products’. [20] Advertising is still the most prevalent form of promotion.

The choice of advertising media depends on your product, target audience, and budget. A travel agency selling spring-break getaways to college students might post flyers on campus bulletin boards or run ads in campus newspapers. The co-founders of Sleep Country Canada found radio ads particularly effective, ingraining their catchy jingle, “why buy a mattress anywhere else?” into listeners nationwide.

Personal Selling

Personal selling refers to one-on-one communication with customers or potential customers. This type of interaction is necessary in selling large-ticket items, such as homes, and it’s also effective in situations in which personal attention helps to close a sale, such as sales of cars and insurance policies.

Many retail stores depend on the expertise and enthusiasm of their salespeople to persuade customers to buy. Home Depot has grown into a home-goods giant in large part because it fosters one-on-one interactions between salespeople and customers. The real difference between Home Depot and everyone else isn’t the merchandise; it’s the friendly, easy-to-understand advice that salespeople give to novice homeowners, according to one of its co-founders.[21] Best Buy’s knowledgeable sales associates make them “uniquely positioned to help consumers navigate the increasing complexity of today’s technological landscape” according to CEO Hubert Joly.[22]

Sales Promotion

It’s likely that at some point, you have purchased an item with a coupon or because it was advertised as a buy-one-get-one special. If so, you have responded to a sales promotion – one of the many ways that sellers provide incentives for customers to buy. Sales promotion activities include not only those mentioned above but also other forms of discounting, sampling, trade shows, in-store displays, and even sweepstakes. Some promotional activities are targeted directly to consumers and are designed to motivate them to purchase now. You’ve probably heard advertisers make statements like “limited time only” or “while supplies last”. If so, you’ve encountered a sales promotion directed at consumers. Other forms of sales promotion are directed at dealers and intermediaries. Trade shows are one example of a dealer-focused promotion. Mammoth convention centres such as the Enercare Centre in Toronto host enormous events in which manufacturers can display their new products to retailers and other interested parties. At food shows, for example, potential buyers can sample products that manufacturers hope to launch to the market. Feedback from prospective buyers can even result in changes to new product formulations or decisions not to launch.

Losing money to make money

A loss leader (also leader) is a pricing strategy where a product is sold at a price below its market cost to stimulate other sales of more profitable goods or services. With this sales promotion/marketing strategy, a “leader” is used as a related term and can mean any popular article, i.e., one sold at a normal price.

One use of a loss leader is to draw customers into a store where they are likely to buy other goods. The vendor expects that the typical customer will purchase other items at the same time as the loss leader and that the profit made on these items will be such that an overall profit is generated for the vendor.

“Loss lead” describes the concept that an item is offered for sale at a reduced price and is intended to “lead” to the subsequent sale of other services or items, the sales of which will be made in greater numbers, or greater profits, or both. The loss leader is offered at a price below its minimum profit margin—not necessarily below cost. The firm tries to maintain a current analysis of its accounts for both the loss leader and the associated items, so it can monitor how well the scheme is doing, as quickly as possible, thereby never suffering an overall net loss.

From Wikipedia

Publicity and Public Relations

Free publicity—say, getting your company or your product mentioned or pictured in a newspaper or on TV—can often generate more customer interest than a costly ad. When Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine were finalizing the development of their Beats headphones, they sent a pair to LeBron James. He liked them so much he asked for 15 more pairs, and they “turned up on the ears of every member of the 2008 U.S. Olympic basketball team when they arrived in Shanghai. ‘Now that’s marketing,’ says Iovine”.[23] It wasn’t long before the pricey headphones became a must-have fashion accessory for everyone from celebrities to high school students.

Consumer perception of a company is often important to a company’s success. Many companies, therefore, manage their public relations in an effort to garner favourable publicity for themselves and their products. When the company does something noteworthy, such as sponsoring a fund-raising event, the public relations department may issue a press release to promote the event. When the company does something negative, such as selling a prescription drug that has unexpected side effects, the public relations department will work to control the damage to the company. Each year the Hay Group and Korn Ferry survey more than a thousand company top executives, directors, and industry leaders in twenty countries to identify companies that have exhibited exceptional integrity or commitment to corporate social responsibility. The rankings are published annually as Fortune magazine’s “World’s Most Admired Companies.®”[24] Topping the list in 2024 are Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JP Morgan Chase (Fortune, 2024).

How Does The Product Life Cycle Affect Promotional Tactics?

During the Product Life Cycle, companies promote their products using several different strategies. These strategies will often change as the company enters into a new stage of the cycle. Below are a few examples of how organizations promote depending on the stage of their product.

The Introduction Stage

The length of the introductory stage varies for different products. However, by law in the United States, a company is only allowed to use the label “new” on a product’s package for six months. An organization’s objectives during the introductory stage often involve educating potential customers about its value and benefits, creating awareness, and getting potential customers to try the product or service. Getting products and services, particularly multinational brands, accepted in foreign markets can take even longer. Consequently, companies introducing products and services abroad generally must have the financial resources to make a long-term (longer than one year) commitment to their success.

The specific promotional strategies a company uses to launch a product vary depending on the type of product and the number of competitors it faces in the market. Firms that manufacture products such as cereals, snacks, toothpastes, soap, and shampoos often use mass marketing techniques such as television commercials and Internet campaigns and promotional programs such as coupons and sampling to reach consumers. To reach wholesalers and retailers such as Walmart, Target, and grocery stores, firms utilize personal selling. Many firms promote to customers, retailers, and wholesalers. Sometimes other, more targeted advertising strategies are employed, such as billboards and transit signs (signs on buses, taxis, subways, and so on). For more technical or expensive products such as computers or plasma televisions, many firms utilize professional selling, informational promotions, and in-store demonstrations so consumers can see how the products work.

The Growth Stage

A company sometimes increases its promotional spending on a product during its growth stage. However, instead of encouraging consumers to try the product, the promotions often focus on the specific benefits the product offers and its value relative to competitive offerings. In other words, although the company must still inform and educate customers, it must counter the competition. Emphasizing the advantages of the product’s brand name can help a company maintain its sales in the face of competition. Although different organizations produce personal computers, a highly recognized brand such as IBM strengthens a firm’s advantage when competitors enter the market. New offerings that utilize the same successful brand name as a company’s already existing offerings, which is what Black & Decker does with some of its products, can give a company a competitive advantage. Companies typically begin to make a profit during the growth stage because more units are being sold and more revenue is generated.

The Maturity Stage

Given the competitive environment in the maturity stage, many products are promoted heavily to consumers by stronger competitors. The strategies used to promote the products often focus on value and benefits that give the offering a competitive advantage. The promotions aimed at a company’s distributors may also increase during the mature stage.

Companies are challenged to develop strategies to extend the maturity stage of their products so they remain competitive. Many firms do so by modifying their target markets, their offerings, or their marketing strategies. Next, we look at each of these strategies.

Modifying the target market helps a company attract different customers by seeking new users, going after different market segments, or finding new uses for a product in order to attract additional customers. Financial institutions and automobile dealers realized that women have increased buying power and now market to them. With the growth in the number of online shoppers, more organizations sell their products and services through the Internet. Entering new markets provides companies with an opportunity to extend the product life cycles of their different offerings.

Many companies enter different geographic markets or international markets as a strategy to get new users. A product that might be in the mature stage in one country might be in the introductory stage in another market. For example, when the U.S. market became saturated, McDonald’s began opening restaurants in foreign markets. Cell phones were very popular in Asia before they were introduced in the United States. Many cell phones in Asia are being used to scan coupons and to charge purchases. However, the market in the United States might not be ready for that type of technology.

Modifying the product, such as changing its packaging, size, flavours, colours, or quality can also extend the product’s maturity stage. The 100 Calorie Packs created by Nabisco provide an example of how a company changed the packaging and size to provide convenience and one-hundred-calorie portions for consumers. While the sales of many packaged foods fell, the sales of the 100 Calorie Packs increased to over $200 million, prompting Nabisco to repackage more products (Hunter, 2008). Kraft Foods extended the mature stage of different crackers such as Wheat Thins and Triscuits by creating different flavours. Although not popular with consumers, many companies downsize (or decrease) the package sizes of their products or the amount of the product in the packages to save money and keep prices from rising too much.

The Decline Stage

Companies must decide what strategies to take when their products enter the decline stage. To save money, some companies try to reduce their promotional expenditures on these products and the number of distribution outlets in which they are sold. Many companies decide the best strategy is to modify the product in the maturity stage to avoid entering the decline stage.

SOURCE: “World’s Most Admired Companies,” https://fortune.com/ranking/worlds-most-admired-companies/search/, accessed July 23, 2024.