11.3 Ethics and Profitability

Few directives in business can override the core mission of maximizing shareholder wealth, and today that particularly means increasing quarterly profits. Such an intense focus on one variable over a short time (i.e., a short-term perspective) leads to a short-sighted view of what constitutes business success.

Measuring true profitability, however, requires taking a long-term perspective. We cannot accurately measure success within a quarter of a year; a longer time is often required for a product or service to find its market and gain traction against competitors, or for the effects of a new business policy to be felt. Satisfying consumers’ demands, going green, being socially responsible, and acting above and beyond the basic requirements all take time and money. However, the extra cost and effort will result in profits in the long run. If we measure success from this longer perspective, we are more likely to understand the positive effect ethical behavior has on all who are associated with a business.

Profitability and Success: Thinking Long Term

Decades ago, some management theorists argued that a conscientious manager in a for-profit setting acts ethically by emphasizing solely the maximization of earnings. Today, most commentators contend that ethical business leadership is grounded in doing right by all stakeholders directly affected by a firm’s operations, including, but not limited to, stockholders, or those who own shares of the company’s stock. That is, business leaders do right when they give thought to what is best for all who have a stake in their companies. Not only that, firms actually reap greater material success when they take such an approach, especially over the long run.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman stated in a now-famous New York Times Magazine article in 1970 that the only “social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits.”

This concept took hold in business and even in business school education. However, although it is certainly permissible and even desirable for a company to pursue profitability as a goal, managers must also have an understanding of the context within which their business operates and of how the wealth they create can add positive value to the world. The context within which they act is society, which permits and facilitates a firm’s existence.

Thus, a company enters a social contract with society as whole, an implicit agreement among all members to cooperate for social benefits. Even as a company pursues the maximizing of stockholder profit, it must also acknowledge that all of society will be affected to some extent by its operations. In return for society’s permission to incorporate and engage in business, a company owes a reciprocal obligation to do what is best for as many of society’s members as possible, regardless of whether they are stockholders. Therefore, when applied specifically to a business, the social contract implies that a company gives back to the society that permits it to exist, benefiting the community at the same time it enriches itself.

What happens when a bank decides to break the social contract? This press conference held by the National Whistleblowers Center describes the events surrounding the $104 million whistleblower reward given to former UBS employee Bradley Birkenfeld by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. While employed at UBS, Switzerland’s largest bank, Birkenfeld assisted in the company’s illegal offshore tax business, and he later served forty months in prison for conspiracy. But he was also the original source of incriminating information that led to a Federal Bureau of Investigation examination of the bank and to the U.S. government’s decision to impose a $780 million fine on UBS in 2009. In addition, Birkenfeld turned over to investigators the account information of more than 4,500 U.S. private clients of UBS.

In addition to taking this more nuanced view of profits, managers must also use a different time frame for obtaining them. Wall Street’s focus on periodic (i.e., quarterly and annual) earnings has led many managers to adopt a short-term perspective, which fails to take into account effects that require a longer time to develop. For example, charitable donations in the form of corporate assets or employees’ volunteered time may not show a return on investment until a sustained effort has been maintained for years. A long-term perspective is a more balanced view of profit maximization that recognizes that the impacts of a business decision may not manifest for a longer time.

As an example, consider the business practices of Toyota when it first introduced its vehicles for sale in the United States in 1957. For many years, Toyota was content to sell its cars at a slight loss because it was accomplishing two business purposes: It was establishing a long-term relationship of trust with those who eventually would become its loyal U.S. customers, and it was attempting to disabuse U.S. consumers of their belief that items made in Japan were cheap and unreliable. The company accomplished both goals by patiently playing its long game, a key aspect of its operational philosophy, “The Toyota Way,” which includes a specific emphasis on long-term business goals, even at the expense of short-term profit.

What contributes to a corporation’s positive image over the long term? Many factors contribute, including a reputation for treating customers and employees fairly and for engaging in business honestly. Companies that act in this way may emerge from any industry or country. Examples include Fluor, the large U.S. engineering and design firm; illycaffè, the Italian food and beverage purveyor; Marriott, the giant U.S. hotelier; and Nokia, the Finnish telecommunications retailer. The upshot is that when consumers are looking for an industry leader to patronize and would-be employees are seeking a firm to join, companies committed to ethical business practices are often the first to come to mind.

Why should stakeholders care about a company acting above and beyond the ethical and legal standards set by society? Simply put, being ethical is simply good business. A business is profitable for many reasons, including expert management teams, focused and happy employees, and worthwhile products and services that meet consumer demand. One more and very important reason is that they maintain a company philosophy and mission to do good for others.

Year after year, the nation’s most admired companies are also among those that had the highest profit margins. Going green, funding charities, and taking a personal interest in employee happiness levels adds to the bottom line! Consumers want to use companies that care for others and our environment. During the years 2008 and 2009, many unethical companies went bankrupt. However, those companies that avoided the “quick buck,” risky and unethical investments, and other unethical business practices often flourished. If nothing else, consumer feedback on social media sites such as Yelp and Facebook can damage an unethical company’s prospects.

Competition and the Markers of Business Success

Perhaps you are still thinking about how you would define success in your career. For our purposes here, let us say that success consists simply of achieving our goals. We each have the ability to choose the goals we hope to accomplish in business, of course, and, if we have chosen them with integrity, our goals and the actions we take to achieve them will be in keeping with our character.

Warren Buffet (Figure 11.3), whom many consider the most successful investor of all time, is an exemplar of business excellence as well as a good potential role model for professionals of integrity and the art of thinking long term. He had the following to say: “Ultimately, there’s one investment that supersedes all others: Invest in yourself. Nobody can take away what you’ve got in yourself, and everybody has potential they haven’t used yet. . . . You’ll have a much more rewarding life not only in terms of how much money you make, but how much fun you have out of life; you’ll make more friends the more interesting person you are, so go to it, invest in yourself.”

The primary principle under which Buffett instructs managers to operate is: “Do nothing you would not be happy to have an unfriendly but intelligent reporter write about on the front page of a newspaper.”

This is a very simple and practical guide to encouraging ethical business behaviour on a personal level. Buffett offers another, equally wise, principle: “Lose money for the firm, even a lot of money, and I will be understanding; lose reputation for the firm, even a shred of reputation, and I will be ruthless.”

As we saw in the example of Toyota, the importance of establishing and maintaining trust in the long term cannot be underestimated.

For more on Warren Buffett’s thoughts about being both an economic and ethical leader, watch this interview that appeared on the PBS NewsHour on June 6, 2017.

Stockholders, Stakeholders, and Goodwill

Earlier in this chapter, we explained that stakeholders are all the individuals and groups affected by a business’s decisions. Among these stakeholders are stockholders (or shareholders), individuals and institutions that own stock (or shares) in a corporation. Understanding the impact of a business decision on the stockholder and various other stakeholders is critical to the ethical conduct of business. Indeed, prioritizing the claims of various stakeholders in the company is one of the most challenging tasks business professionals face. Considering only stockholders can often result in unethical decisions; the impact on all stakeholders must be considered and rationally assessed.

Managers do sometimes focus predominantly on stockholders, especially those holding the largest number of shares because these powerful individuals and groups can influence whether managers keep their jobs or are dismissed (e.g., when they are held accountable for the company’s missing projected profit goals). And many believe the sole purpose of a business is, in fact, to maximize stockholders’ short-term profits. However, considering only stockholders and short-term impacts on them is one of the most common errors business managers make. It is often in the long-term interests of a business not to accommodate stockowners alone but rather to take into account a broad array of stakeholders and the long-term and short-term consequences for a course of action.

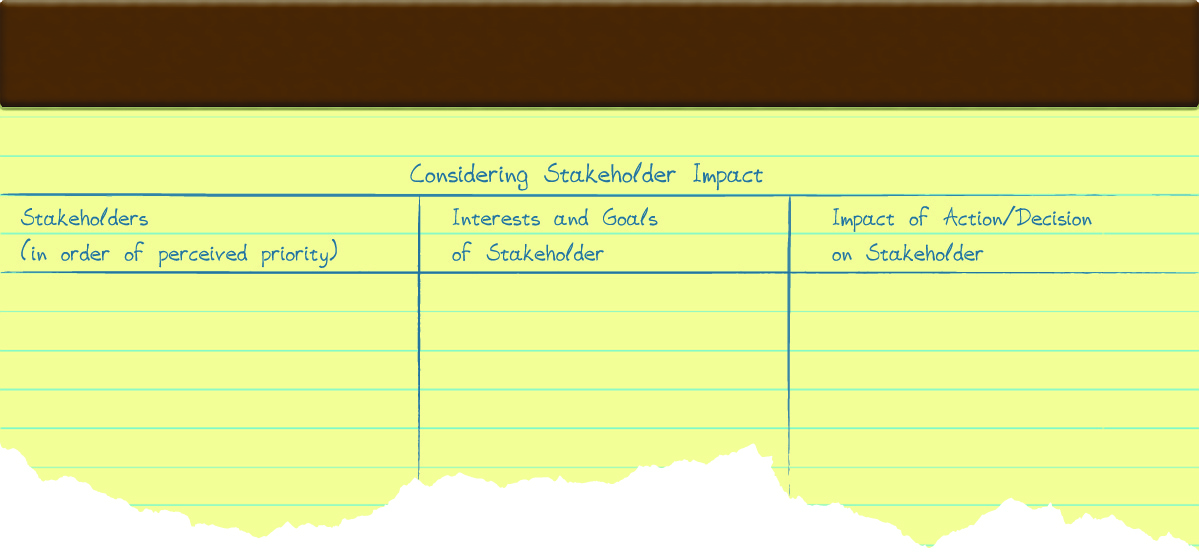

Here is a simple strategy for considering all your stakeholders in practice. Divide your screen or page into three columns; in the first column, list all stakeholders in order of perceived priority (Figure 11.4: Considering Stakeholder Impact). Some individuals and groups play more than one role. For instance, some employees may be stockholders, some members of the community may be suppliers, and the government may be a customer of the firm. In the second column, list what you think each stakeholder group’s interests and goals are. For those that play more than one role, choose the interests most directly affected by your actions. In the third column, put the likely impact of your business decision on each stakeholder. This basic spreadsheet should help you identify all your stakeholders and evaluate your decision’s impact on their interests. If you would like to add a human dimension to your analysis, try assigning some of your colleagues to the role of stakeholders and reexamine your analysis.

The positive feeling stakeholders have for any particular company is called goodwill, which is an important component of almost any business entity, even though it is not directly attributable to the company’s assets and liabilities. Among other intangible assets, goodwill might include the worth of a business’s reputation, the value of its brand name, the intellectual capital and attitude of its workforce, and the loyalty of its established customer base. Even being socially responsible generates goodwill. The ethical behaviour of managers will have a positive influence on the value of each of those components. Goodwill cannot be earned or created in a short time, but it can be the key to success and profitability.

A company’s name, its corporate logo, and its trademark will necessarily increase in value as stakeholders view that company in a more favourable light. A good reputation is essential for success in the modern business world, and with information about the company and its actions readily available via mass media and the Internet (e.g., on public rating sites such as Yelp), management’s values are always subject to scrutiny and open debate. These values affect the environment outside and inside the company. The corporate culture, for instance, consists of shared beliefs, values, and behaviours that create the internal or organizational context within which managers and employees interact. Practicing ethical behaviour at all levels—from CEO to upper and middle management to general employees—helps cultivate an ethical corporate culture and ethical employee relations.

Which Corporate Culture Do You Value?

Imagine that upon graduation you have the good fortune to be offered two job opportunities. The first is with a corporation known to cultivate a hard-nosed, no-nonsense business culture in which keeping long hours and working intensely are highly valued. At the end of each year, the company donates to numerous social and environmental causes. The second job opportunity is with a nonprofit recognized for a very different culture based on its compassionate approach to employee work-life balance. It also offers the chance to pursue your own professional interests or volunteerism during a portion of every workday. The first job offer pays 20 percent more per year.

Positive goodwill generated by ethical business practices, in turn, generates long-term business success. As recent studies have shown, the most ethical and enlightened companies in the United States consistently outperform their competitors.

Thus, viewed from the proper long-term perspective, conducting business ethically is a wise business decision that generates goodwill for the company among stakeholders, contributes to a positive corporate culture, and ultimately supports profitability.

You can test the validity of this claim yourself. When you choose a company with which to do business, what factors influence your choice? Let us say you are looking for a financial advisor for your investments and retirement planning, and you have found several candidates whose credentials, experience, and fees are approximately the same. Yet one of these firms stands above the others because it has a reputation, which you discover is well earned, for telling clients the truth and recommending investments that seemed centered on the clients’ benefit and not on potential profit for the firm. Wouldn’t this be the one you would trust with your investments?

Or suppose one group of financial advisors has a long track record of giving back to the community of which it is part. It donates to charitable organizations in local neighbourhoods, and its members volunteer service hours toward worthy projects in town. Would this group not strike you as the one worthy of your investments? That it appears to be committed to building up the local community might be enough to persuade you to give it your business. This is exactly how a long-term investment in community goodwill can produce a long pipeline of potential clients and customers.

The Equifax Data Breach

In 2017, from mid-May to July, hackers gained unauthorized access to servers used by Equifax, a major credit reporting agency, and accessed the personal information of nearly one-half the U.S. population.

Equifax executives sold off nearly $2 million of company stock they owned after finding out about the hack in late July, weeks before it was publicly announced on September 7, 2017, in potential violation of insider trading rules. The company’s shares fell nearly 14 percent after the announcement, but few expect Equifax managers to be held liable for their mistakes, face any regulatory discipline, or pay any penalties for profiting from their actions. To make amends to customers and clients in the aftermath of the hack, the company offered free credit monitoring and identity theft protection. On September 15, 2017, the company’s chief information officer and chief of security retired. On September 26, 2017, the CEO resigned, days before he was to testify before Congress about the breach. To date, numerous government investigations and hundreds of private lawsuits have been filed as a result of the hack.

A Brief Introduction to Corporate Social Responsibility

If you truly appreciate the positions of your various stakeholders, you will be well on your way to understanding the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR). CSR is the practice by which a business views itself within a broader context, as a member of society with certain implicit social obligations and environmental responsibilities. As previously stated, there is a distinct difference between legal compliance and ethical responsibility, and the law does not fully address all ethical dilemmas that businesses face. CSR ensures that a company is engaging in sound ethical practices and policies in accordance with the company’s culture and mission, above and beyond any mandatory legal standards. A business that practices CSR cannot have maximizing shareholder wealth as its sole purpose, because this goal would necessarily infringe on the rights of other stakeholders in the broader society. For instance, a mining company that disregards its corporate social responsibility may infringe on the right of its local community to clean air and water if it pursues only profit. In contrast, CSR places all stakeholders within a proper contextual framework.

An additional perspective to take concerning CSR is that ethical business leaders opt to do good at the same time that they do well. This is a simplistic summation, but it speaks to how CSR plays out within any corporate setting. The idea is that a corporation is entitled to make money, but it should not only make money. It should also be a good civic neighbour and commit itself to the general prospering of society as a whole. It ought to make the communities of which it is part better at the same time it pursues legitimate profit goals. These ends are not mutually exclusive, and it is possible—indeed, praiseworthy—to strive for both. When a company approaches business in this fashion, it is engaging in a commitment to corporate social responsibility.

U.S. entrepreneur Blake Mycoskie has created a unique business model combining both for-profit and nonprofit philosophies in an innovative demonstration of corporate social responsibility. The company he founded, TOMS Shoes, donates one pair of shoes to a child in need for every pair sold. As of May 2018, the company has provided more than 75 million pairs of shoes to children in seventy countries.

Summary

A long-term view of business success is critical for accurately measuring profitability. All the company’s stakeholders benefit from managers’ ethical conduct, which also increases a business’s goodwill and, in turn, supports profitability. Customers and clients tend to trust a business that gives evidence of its commitment to a positive long-term impact. By exercising corporate social responsibility, or CSR, a business views itself within a broader context, as a member of society with certain implicit social obligations and responsibility for its own effects on environmental and social well-being.